He Was a Straight A Student: Jordan Edwards, Richard Collins III, and the Questioning of Black Victimhood

He was a straight A student.

This is a phrase that has become synonymous with the killing of black youth, an utterance that can be characterized as a desperate plea on the part of those expressing it, as they implore others to recognize the worthiness of the young black victim.

In recent weeks, two high profile killings of black men have seen similar attempts to legitimize their status as victims in ways that have also acted to reinforce toxic stereotypes about the innate criminality of black people.

In the days following the death of Jordan Edwards, a 15-year-old black teenager shot in the head by white police officer, Roy Oliver, references to Jordan’s school record and athletic ability featured heavily in media coverage. In the most recent case of anti-black violence – the murder of Richard Collins III on the University of Maryland campus this past Saturday – a spokesperson for the family stressed that Collins, “…was not a thug.”

Both these cases highlight not only the assumed guilt and criminalization of black men and women that permeates American society, but at a deeper level, the immediate struggle faced by grieving families of black victims, who are forced to defend the image of their loved ones in public discourse.

The Deaths of Jordan Edwards and Richard Collins III

Jordan Edwards had been attending a party with his brothers in Balch Spring, a suburb of Dallas, Texas. At approximately 11 p.m., as Jordan and his brothers attempted to leave the party, their car was intercepted by Balch Spring police officers responding to a call about underage drinking. This otherwise standard dispersal of a teenage party somehow ended in the violent death of Jordan Edwards.

The Balch Spring police department quickly released an official version of the event in what has become the boilerplate response to shootings of young black men and women. The statement detailed how, upon arrival, responding officers heard what they believed to be gunshots and then witnessed the car that Jordan was a passenger in “reversing in an aggressive manner.” This account was quickly retracted following the chief’s review of the body-cam footage, which shows that the car was, in fact, driving away and not reversing when the shots were fired. In explaining the discrepancy between the department’s initial account of events and video footage, Balch Spring Police Chief Jonathan Haber stated, “I unintentionally [was] incorrect when I said the vehicle was backing down the road… I’m saying after reviewing the video that I don’t believe [the shooting] met our core values.”

As noted by The Atlantic writer David Graham, the Jordan Edwards case is crucial as the first high profile case of its kind in the Trump era. But beyond calling into question the state of race relations under the current administration and the crucial role body-and-dash cameras can play in holding police departments accountable, the Edwards case is emblematic of the demonization and questioning of black victims of anti-black violence.

This need to justify the victimhood of black people is not restricted to victims of police brutality, but also in cases involving citizens. The recent murder of Richard Collins III is illustrative of this point. While waiting for a taxi on the University of Maryland campus with a friend on May 20, Collins was stabbed by Sean Urbanski, a white man who was a member of a white supremacist Facebook group called Alt Reich: Nation. Since Collins’ death, many media reports have again focused on the victim’s upcoming graduation and plans to serve in the military. As one commentator on social media noted in response to media coverage of Collins’ death, “When it is necessary to assure people that a man murdered at random by a stranger was ‘not a thug’ a nation’s racial pathology is acute.”

Social Media Discussions

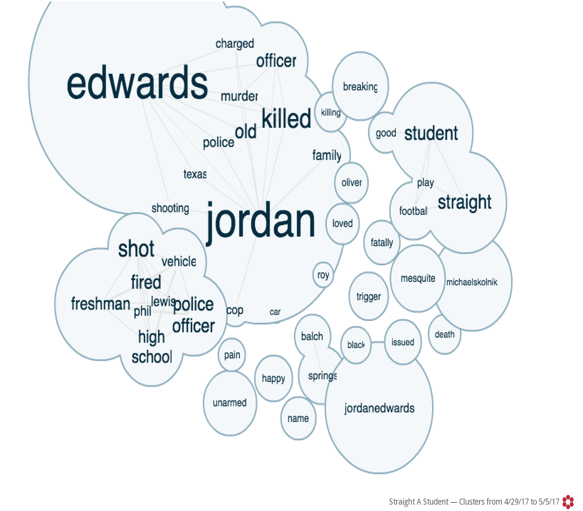

In an effort to analyze this phenomenon, we made use of the social listening tool, Crimson Hexagon, to track discussion of the case since Jordan Edwards’ death on April 29. Between April 29 and May 5, over 190,000 social media posts were generated touching on Edwards’ death. As seen in the cluster analysis above, which visualizes the words and phrases most likely to be included/associated with posts making reference to Edwards – the terms “good,” “student,” “straight,” and to a lesser extent, “football” and “unarmed” feature heavily in social media posts related to the case.

An examination of the top Tweets associated with the case reveals a similar trend. As seen in Figure 2, which is a list of the most frequent retweets, including those done via the retweet button as well as those done manually, the most retweeted post (by Huffington Post editor Phil Lewis) makes reference to Edwards being a “straight-A student,” a point reiterated by Shaun King, and a myriad of news articles. Friends and family expressing shock followed a similar framework, with a parent of Edwards’ teammate making the declaration that “Jordan was not a thug.”

The cases of Jordan Edwards, Richard Collins, and others like them point to the pressing need for those invested in racial justice to both challenge and reframe the current discussion of black victimhood. As noted by author Jemar Tisby in his recent CNN article, the fact that Edwards’ worth has to be tied to his grades or athletic ability adds another layer of sadness to this tragedy. As Tisby states,

…if you think Jordan didn’t deserve to die because he was a good student, then you’re missing the point. Jordan’s achievements don’t make him any more valuable than a person who had trouble in school and a history of bad decisions.

This is a point echoed by writer and academic Zoe Samudzi, in reference to the overemphasis on Edwards’ academics and attempt by the family lawyer to uplift Jordan as a “perfect victim”… “These appeals to innocence assume the default condition of black people is criminal, until public opinion is persuaded to understand them as unique cases not representative of black people as a whole.” Such a dynamic means that no matter the situation or how much evidence there is to support a case for anti-black violence, the innocence of black victims is always in question.

So what can be done?

Racial justice advocates must challenge the assumed guilt and criminality of black Americans – in a way that is affirmative. They can do this by not reinforcing negative stereotypes and pathologies.

Remember that an affirmative position is more powerful than a defensive one. As noted by Julie-Fisher Rowe of The Opportunity Agenda, “Once you’ve made the decision to engage a messaging opponent on their terms, within a conversation that they started, within their metaphors, you are facing an uphill trek.”

Practical solutions for those reporting or commenting on a case of anti-black violence include:

- Acknowledging that anti-black violence is a reality;

- Remembering that black victims are not on trial;

- Focusing on the record of the police officer or civilian involved in the killing;

- Challenging coded discourse (much unpacking still needs to be done to fully unearth entrenched anti-black sentiment in America. Unpacking these hidden and toxic narratives is essential to effectively countering them.)

- Supporting the right of black families to grieve and express anger in the days following such an incident.