The State of Housing in New Orleans One Year After Katrina

Executive Summary

This report assesses the state of housing in New Orleans one year after Hurricane Katrina. It analyzes housing conditions in the city prior to the storm, progress made since, and areas in which the rebuilding effort has fallen short. In addition, it offers practical recommendations to ensure the reconstruction of housing is faster, fairer, and more effective.

Housing has long been central to opportunity and the American Dream. Our homes determine our access to schools, jobs, safety, health care, and political participation. They are a source of shelter, pride, and community. And homeownership provides the chief source of wealth building for millions of Americans. In short, fair and affordable housing is central to the very promise of opportunity—the idea that everyone deserves a fair chance to achieve his or her full potential.

Our research reveals that the natural disaster of Katrina uncovered and exacerbated existing man-made threats to fair and affordable housing, which have been created by specific policy decisions and years of neglect. The resulting lack of affordable units, low rates of homeownership, racial discrimination, and residential segregation, combined with a slow and uneven reconstruction effort, pose steep barriers to displaced and returning residents hoping to start over. Such characteristics limit residents’ chances of recovering from the storm as well as the entire region’s ability to rebuild.

Fortunately, effective tools and strategies exist to reverse these trends and to expand housing opportunity for all people in the region. In particular, reinvesting in effective government systems, many of which are already available, is key to creating safe, accessible, and affordable housing for the people of the region.

The report’s key findings include:

- The pre-Katrina shortage of affordable housing in New Orleans has since erupted into a major crisis, robbing tens of thousands of displaced residents of their right to return. This crisis is disproportionately borne by the region’s poorest residents: a full 20% of the 82,000 rental units that Katrina damaged or destroyed in Louisiana were affordable to extremely low-income households.

- The large loss of habitable rental space has caused sharp rent increases in many damaged areas.

- The plans of the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to demolish four of the city’s largest public housing complexes instead of repairing and reopening them will further hamper returning residents’ opportunity to start over.

- The affordable housing shortage is now accompanied by a failure to restore the neighborhood conditions and infrastructure that nourish and foster community. As of July 2006:

- Only 18% of public schools have reopened.

- Only 21% of child-care centers have reopened.

- A mere 17% of public buses are operational.

- Only 60% of homes have electricity service.

- In the city of New Orleans only 50% of hospitals have reopened.

- Over 100,000 evacuated households were still in Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) trailers as of May 2006, with 1,800 trailers in Alabama, 34,000 in Mississippi, and the majority—68,000—in Louisiana. These trailer communities are geographically isolated, leaving residents with limited access to the opportunities, resources, and community they need to start rebuilding their lives.

- Evidence indicates that, throughout the Gulf Coast, displaced African Americans seeking apartments have experienced housing discrimination, receiving significantly worse treatment than white apartment seekers.

To meet these challenges the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), The Opportunity Agenda, and the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity propose a Housing Opportunity Action Plan, which includes short- and long-term recommendations. Key to this plan is reinvesting in effective government systems that have a track record of promoting housing opportunity.

Recommendations for immediate action include:

- Authorizing additional housing vouchers to ensure that a portion of rebuilt housing is affordable to low-income households.

- Preserving existing federal housing resources by repairing and reopening—rather than demolishing—habitable public housing and replacing all destroyed units.

- Shifting all temporary rental assistance programs to HUD’s Disaster Voucher Program in order to draw upon HUD’s experience in administering housing assistance and the infrastructure of public housing agencies.

- Focusing federal civil-rights enforcement efforts on the Gulf Coast region and Katrina’s diaspora with an emphasis on Fair Housing Act enforcement.

Recommendations for longer-term reforms include:

- Requiring a Housing Opportunity Impact Statement as a condition of public support for future rebuilding efforts.

- Creating incentives for the development of mixed-income neighborhoods with equal access to quality schools, health care, jobs, and other stepping-stones to opportunity.

- Fully funding the repair and rehabilitation of privately owned housing stock.

- Promoting homeownership among low-income families through down-payment- assistance programs and rent-to-own programs.

Finally, because many of the housing problems revealed by Katrina flow from national trends, we call for a new national vision that expands housing opportunity for all Americans. Our long-term recommendations include scaling up many of the reforms described above to reach Americans drowning on dry land without access to safe, fair and affordable housing. In particular, federal and state policies should promote inclusionary zoning, an important tool with a proven track record in encouraging mixed-income housing. The Home Mortgage Data Reporting Act should also be expanded, and the Federal Reserve Bank should step up its fair-lending oversight to prevent discriminatory and predatory lending practices. When tax incentives and other indirect means of encouragement fail, state and federal governments must support the development of new affordable housing.

In a country in which we are increasingly interconnected, we must invest in increasing opportunity for all our residents. Ensuring housing opportunity for all is an investment in the prosperity of our nation that will provide returns for many years to come.

Introduction

Hurricane Katrina made landfall on Monday, August 29, 2005, as a Category 4 hurricane. It passed within 15 miles of New Orleans, Louisiana. The storm brought heavy winds and rain to the city, and the rising water breached several levees built to protect New Orleans from Lake Pontchartrain. The levee breaches flooded up to 80% of the city, with water in some places as high as 25 feet. The storm and flooding took over 1,500 lives and displaced an estimated 700,000 residents.1

Katrina and the levee breaches devastated the homes of hundreds of thousands of New Orleans residents. Nearly 228,000 homes and apartments in New Orleans were flooded, including 39% of all owner-occupied units and 56% of all rental units.2 Approximately 204,700 housing units in Louisiana either were destroyed or sustained major damage. As of April 2006, 360,000 Louisiana residents remained displaced outside the state.3 Some 61,900 people were living in FEMA trailers and mobile homes.4

As the floodwaters receded, displaced residents began the difficult process of rebuilding their lives. Many viewed returning to their communities as a critical step in that process—but one that required access to safe, affordable housing that the state and federal government still has not helped to provide.

This report assesses the state of housing in New Orleans one year after Katrina. It analyzes housing conditions in the city prior to the storm, progress made since, and areas in which the rebuilding effort has fallen short. In addition, it offers practical recommendations to ensure the reconstruction of housing is faster, fairer, and more effective.

Our research reveals that the natural disaster of Katrina uncovered and exacerbated existing man-made threats to fair and affordable housing, created by specific policy decisions and years of neglect. The resulting lack of affordable units, low rates of homeownership, racial discrimination and residential segregation combined with a slow and uneven reconstruction effort pose steep barriers to displaced and returning residents hoping to start over. Such characteristics limit both residents’ chances of recovering from the storm as well as the entire region’s ability to rebuild.

Fortunately, effective tools and strategies exist to reverse these trends and to expand housing opportunity for all in the region. In particular, reinvesting in effective government systems, many of which are already available, is key to creating safe, accessible, and affordable housing for the people of the region.

We acknowledge that resolving the housing crisis in New Orleans will not be easy. Rebuilding the city presents challenges that our country has rarely, if ever, faced. But doing so is crucial not only to the people of New Orleans but also to our national values and our strength as a country. Our ability and resolve to provide a way home for all New Orleanians—no matter their race, ethnicity, income level, or gender—are a test of our resources but also of our moral fiber as a nation. Ensuring that displaced residents receive fair treatment, economic security, a voice in decisions that affect them, and a right of return5 to their communities is core to our national identity as a land of opportunity.

Research and experience show that it is within our power as a society to rebuild New Orleans through strategies that expand opportunity for all. Key to these strategies is a positive and effective role for government in promoting safety and ensuring fairness. A renewed partnership between our government and our people, all of us looking forward while heeding the lessons of the past, can achieve these goals and serve as a model for our nation. We all have a role to play in creating cohesive communities. But it is government’s responsibility to establish public priorities and set rules that reflect our national values. When government has kept the doors of opportunity open, the American people have always been quick to walk through them.

Why focus on housing amid the many challenges facing New Orleans? Housing has long been central to opportunity and the American Dream. Our homes determine our access to schools, jobs, safety, health care, and political participation. They are a source of shelter, pride, and community. And homeownership provides the chief source of wealth building for millions of Americans. In short, fair and affordable housing is central to the very promise of opportunity—the idea that everyone deserves a fair chance to achieve his or her full potential.

It is from these fundamental principles—opportunity, fairness, and government of, by and for the people—that we at the NAACP, The Opportunity Agenda, and the Kirwan Institute report our findings and offer our recommendations for the rebuilding of housing in New Orleans.

Housing Conditions in New Orleans Prior to Katrina

Before Katrina struck, the people of New Orleans faced significant barriers to housing opportunity, including a severe shortage of affordable housing, a low homeownership rate, problematic housing policies, and acute racial and economic segregation. Understanding that landscape, and the decisions that caused it, is important in avoiding the problems of the past and in pursuing a fair and effective reconstruction process that can fulfill the promise of opportunity.

A Lack of Affordable Housing

Like most cities across the country, New Orleans already had an affordable housing shortage before Katrina. Two-thirds (67%) of extremely low-income households in New Orleans bore housing costs that exceed 30% of income, considered excessive under federal standards, and more than half (56%) of very low-income households paid more than half their income for housing.6

Low Homeownership Rates

Before the flooding, New Orleans already had a low homeownership rate–only 47% compared to 67% nationally.7 Of those owning homes, rates were not even among residents as African American and low-income families in New Orleans had far lower rates of homeownership than whites and higher-income families.8

Segregated Neighborhoods

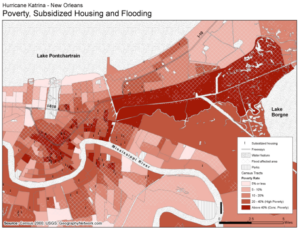

New Orleans suffered acute residential segregation prior to Hurricane Katrina’s landfall, which contributed to the disproportionate impact of the storm on low-income and minority communities. Indeed, the city and region have an extensive history of legal segregation,9 which continued long after the U.S. Supreme Court’s decisions in Shelley v. Kramer10 and Brown v. Board of Education11 struck down racially restrictive covenants and legal segregation, respectively.

That pattern and practice of discrimination at times included the direct participation of the federal government. In 1969, for example, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana found that the U.S. Department of HUD’s practice of intentionally concentrating New Orleans’ public housing in African American neighborhoods violated the U.S. Constitution.12 The court said of HUD’s actions:

[T]he dominant factor in selecting sites for the location of public housing was the racial concentration of the neighborhoods. Its purpose was to perpetuate segregation of the races in public housing, and the present location of the sites will most likely perpetuate segregation. This is rank discrimination forbidden by both the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and [the Civil Rights Act of 1964].13

As a result of this history, New Orleans remained highly segregated when Katrina hit. While residential segregation in the city declined slightly between 1990 and 2000, it continued to remain significantly above the national average.14 U.S. Census Bureau figures from 2000 ranked New Orleans the 11th most-segregated city among large U.S. metropolitan areas.15

Racial segregation also played a part in the economic segregation of New Orleans, resulting in racially segregated high- and concentrated-poverty neighborhoods. Before Katrina, New Orleans had the second-highest rate of African American concentrated poverty in the nation, with 37% of the city’s African American population living in neighborhoods of concentrated poverty.

Residing in areas of concentrated poverty depresses life outcomes and often results in isolation from the social, educational and economic opportunities necessary to better one’s life. Research by the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at The Ohio State University found that New Orleans neighborhoods with higher concentrations of African Americans, like the Lower Ninth Ward, Central City and St. Roch, were primarily “low opportunity” areas with limited access to quality schools, jobs, and safety from crime.16

After Katrina hit, these racially and economically segregated areas bore the brunt of the disaster. More than three-quarters of concentrated-poverty areas were flooded.17 And 80% of residents in the most flooded areas were nonwhite.18

Barriers to Equitable Housing Opportunities in New Orleans Since Katrina

Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath displaced hundreds of thousands of New Orleans residents, creating a diaspora of hurricane survivors around the region and across the country.19 Despite public promises, the rebuilding process has been unacceptably slow, and has poorly served African Americans and low-income residents—the very people who bore the brunt of the storm. Moreover, many aspects of the reconstruction threaten to worsen rather than redress the problems of high housing costs, discrimination, and segregation that existed in pre-Katrina New Orleans.

The Lack of Affordable Rental Housing

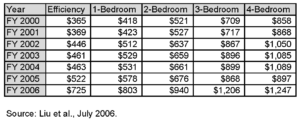

The shortage of affordable housing that existed in pre-Katrina New Orleans has since erupted into a major crisis, robbing thousands of displaced residents of their right to return.20 Hurricane Katrina damaged or destroyed 82,000 rental units in Louisiana, a fifth of which were affordable to extremely low-income households.21 The large loss of habitable rental space in many damaged areas has caused sharp rent increases. As the following table from the Brookings Institute shows, since fiscal year 2000 fair market rents in New Orleans are now at their highest levels, surpassing pre-Katrina rent prices:22

Despite this severe shortage of affordable housing, of the entire $11.5 billion Community Development Bloc Grant allocation for Louisiana, just $920 million is targeted towards rental housing for extremely low-and very-low-income people.23

Because affordable permanent housing has yet to be made available for returning residents, the number of occupied emergency trailers and mobile homes has swelled by 30,164 units since March 2006, while the number of households receiving rental assistance has increased by 33,350.24

This situation is not only preventing displaced residents from returning, but also hampering the rebuilding process. Housing available to reconstruction workers—the people doing the hard work of rebuilding the city—is inadequate and often inhumane. A recent survey by the Advancement Project indicated that:

- Housing for reconstruction laborers is severely limited. Many live near construction sites in hotel rooms and shared apartments, and some even in cars or at the work sites.

- On average, construction workers share housing with five others.

- Over two-thirds of the construction workers surveyed have children, but less than half reported having had their families relocate with them to the Gulf Coast.25

Public Housing

Despite the lack of housing for low-income people, HUD intends to demolish four of the city’s largest public housing complexes: St. Bernard, C.J. Peete, B.W. Cooper and Lafitte. The agency also intends to reopen 1,000 units of housing by August 2006 in the Iberville, Guste, Fischer, River Garden and Hendee Homes complexes.26 But opening these units will not begin to meet the city’s need as an additional 3,000 units will still be necessary to bring New Orleans’ capacity back to pre-Katrina levels.27

Homeownership

The uneven rebuilding effort will likely exacerbate the existing racial gap in homeownership in New Orleans. Despite a low homeownership rate in New Orleans in general, many of the African American neighborhoods devastated by flooding had high ownership rates. The Lower Ninth Ward, which was 96% African American, had a homeownership rate of 54%. Similar characteristics were found in New Orleans East (86% African American, 55% homeownership rate) and Gentilly (70% African American, 72% homeownership rate).28 But many of the homeowners within these neighborhoods did not have flood and hazard insurance, creating a significant impediment to rebuilding. Approximately one-quarter of homeowners in New Orleans East and Gentilly and two-thirds of homeowners in the Lower Ninth Ward lacked insurance.29

Emergency Housing

Largely as a result of the lack of affordable housing, over 100,000 evacuated households still lived in FEMA trailers as of May 2006, with 1,800 travel trailers in Alabama, 34,000 in Mississippi and 68,000 in Louisiana. These trailer communities are geographically isolated, leaving residents with limited access to the opportunities and resources necessary to rebuild their lives.30 In addition, households in FEMA emergency housing are frequently forced to live in deplorable conditions. Thousands of displaced evacuees from New Orleans and its vicinity (St. Bernard, Cameron, Vermilion and Jefferson Davis parishes) have found themselves stuck in what the Washington Post described as “squalid, miserable, dangerous FEMA trailer ‘villages.’”31

Discrimination

Evidence indicates that throughout the Gulf Coast, displaced African Americans seeking apartments have experienced housing discrimination, receiving significantly worse treatment than white apartment seekers. A study conducted by the National Fair Housing Alliance found persistent housing discrimination on the basis of race. In phone tests that had white and African American individuals call numerous housing complexes, white home seekers were more likely to be told about apartment availability, rent, and discounts. Their African American counterparts were often denied this information. This study, involving housing complexes in seventeen cities and five states affected by the 2005 hurricanes, found that apartment complexes:

- Failed to tell African Americans about available apartments, but told white callers that one or more units were available.

- Failed to return telephone messages left by African Americans.

- Failed to provide the correct information, or any information, to African American testers regarding the number of available units, rental price range, and security deposits.

- Quoted higher rent and security deposit prices to African American testers. In one case, a white tester was told that her security deposit and application fee would be waived because of her status as a Hurricane Katrina victim, while an African American hurricane survivor had to pay both.

- Offered special discounts to white renters. An example in Dallas illustrates that both white testers were offered a free 26-inch LCD television for renting at a particular complex. One of the white renters was told that there would be a $100 refundable security deposit plus a $400 admission fee, and the other was told that the security deposit was $500 with $100 refundable. An African American tester was not told about the television, but was notified that she would have to pay a $500 admission fee, as well as a nonrefundable $500 security deposit.32

These practices illustrate the potential re-establishment of segregation that existed in the region before Katrina, and to cut African Americans off from the traditional stepping-stones to opportunity—quality housing, schools, jobs, health care, and transportation.

The Loss of Community

In many neighborhoods in New Orleans, schools are not opening, health-care services are not available, and homes are not being rebuilt. In other words, community is being lost. Even if all the homes were rebuilt and all the residents returned, New Orleans would remain in crisis without the rebuilding of community characteristics that promote opportunity. For example, as of July 2006:

- Only 18% of public schools have reopened.

- Just 21% of child-care centers have reopened.

- A mere 17% of public buses are operational.

- Only 60% of homes have electricity service.33

In Louisiana 30 hospitals initially closed due to hurricane damage, and only 10 had reopened as of March 9, 2006.34 In the city of New Orleans only 50% of hospitals have been reopened.35

The Result: Unequal Opportunity to Return

As a result of the unfair and inadequate rebuilding process, the most vulnerable groups have faced the steepest barriers. Disparate opportunities for Gulf residents to return to their homes are creating rapid demographic shifts in the population. Low- income communities and people of color now make up a smaller percentage of the New Orleans metropolitan population.36 Because of the population shift and uneven return migration, the disparity in wealth is likely to influence which neighborhoods are rebuilt and which ones are not, further impeding low-income and minority communities from returning.37

In addition to the basic fairness of allowing everyone to return home, recent research has shown that African Americans who return fare better in finding employment. According to the Economic Policy Institute, only 32% of African American evacuees who have not returned have found jobs, while the rate is 60% – the same as for whites – among those who have returned.38

A National Challenge

In some ways, New Orleans represents an exceptional situation: as a highly segregated, high-poverty city with limited housing opportunity beset by multiple hurricanes and a catastrophic flood. But many of New Orleans’ housing problems—the lack of affordable housing, stagnant homeownership rates, residential segregation, and persistent discrimination— represent national trends away from opportunity for Americans across the country. Just as low-income Americans and communities of color are bearing the brunt of these forces in New Orleans today, those groups face the highest barriers to housing opportunity nationally.

After a period of significant national progress in making affordable housing and homeownership fair and accessible, our nation’s progress has stalled and, in some instances, the country is losing ground. For example, as noted in The Opportunity Agenda’s report The State of Opportunity in America:39

- Nationally, of the 4.4 million “working poor” households in the United States, nearly 60% pay more than half of their incomes for housing or live in dilapidated conditions. These families—most of whom include children—are more likely to have trouble paying household bills, to lack health insurance, and to experience hunger.

- Homeownership has slightly increased nationally over the last 25 years, from a 65.4% homeownership rate in 1979 to 68.3% in 2003. But large gaps in homeownership exist among income, racial, and ethnic groups. For example, between 1970 and 2003, homeownership among the top 20% of wage earners grew by over 10%, while slightly declining among the lowest fifth of wage earners. African American and Latino households are also far less likely to own homes than whites. Although this gap has narrowed slightly, it is large, and has persisted for decades.

- Nationally, according to a 2000 HUD study of cities across the country, landlords and real estate agents favored whites seeking rental housing over similarly-qualified African Americans 22% of the time, and over Hispanics 26% of the time. Asian Americans and Native Americans also faced significant levels of housing discrimination.

- Low-income African Americans are 7.3 times more likely than whites to live in high poverty neighborhoods (those with 30% or more living in poverty)—a gap that has increased almost 100% since 1960.40

- HUD data show that African Americans, Latinos, Native Americans and Pacific Islanders are more likely than whites to receive higher interest sub prime loans in the vast majority of U.S. metropolitan areas. These racial disparities are higher among more affluent borrowers than among less affluent ones.41

These findings make clear that New Orleans is not unique in facing a crisis in fair and affordable housing. While the extreme circumstances of the Gulf Coast demand immediate action, housing opportunity is a national concern that requires a swift and sure federal response.

Next Steps: A Housing Opportunity Plan for New Orleans and the Nation

Katrina exposed stark racial and economic inequalities that many Americans thought no longer existed in our country. In rebuilding New Orleans, we have a historic opportunity to reverse these trends in ways that will benefit all communities. It is not too late to dismantle residential segregation and promote housing opportunity for all Gulf Coast communities. Federal, state, and local officials must act immediately to speed the rebuilding process, to prioritize affordable housing, and to ensure that the burdens and benefits of rebuilding are shared by all, whatever their race or income.

To meet that challenge, the NAACP, The Opportunity Agenda and the Kirwan Institute propose a Housing Opportunity Action Plan that includes short-term and long- term recommendations. Key to this plan is reinvesting in effective government systems with a track record of promoting housing opportunity. Many of these systems are already available and require only adequate funding, activation or enforcement. In other cases, significant policy changes are needed to address the current challenge.

Recommendations for immediate action include:

- Shift all temporary rental assistance programs to HUD’s Disaster Voucher Program (DVP). The households remaining in FEMA’s transitional housing assistance program, and in state and local voucher programs, should be assisted instead through HUD’s DVP. Shifting responsibility would take advantage of HUD’s experience in administering housing assistance to people in need, as well as the infrastructure of public housing agencies that already administer two million vouchers nationwide. It would provide more flexibility and choice for displaced families, security to landlords who rent to evacuees and improved federal oversight of the use of federal resources. Additionally, such a shift would rectify the myriad of problems facing the approximately 200,000 households currently in FEMA’s transitional housing assistance program.42

- Authorize additional housing vouchers to ensure that a portion of rebuilt private housing is affordable to low- income households. Section 8 vouchers can be a part of the long-run solution, as long as funding is adequate for displaced residents to obtain market rate housing. Section 8 vouchers must be truly portable, allowing recipients to look for housing beyond areas of concentrated poverty.43

- Assist low- income homeowners in their efforts to repair or replace damaged homes. Much of the assistance provided, like that from the Small Business Administration, is unattainable for low-income households, who often have difficulty meeting repayment conditions. Additional funds must be provided to address this need.44

- Preserve existing federal housing resources in the Gulf. Because most of the subsidized housing in the region was destroyed, it must be rebuilt for those who need affordable housing. The Secretaries of HUD and the Department of Agriculture should act now to preserve or replace, on a one-for one basis, all federally assisted housing in the affected areas. Public housing and other federally subsidized housing that was not damaged should immediately be reopened and former tenants should be allowed to return. Developments or units that were damaged beyond repair should be rebuilt in a manner ensuring all former tenants a right to return. As former tenants await the reconstruction of their homes, they must be guaranteed temporary, affordable housing.45

- Require that HUD make its plan for New Orleans public housing available for public input. Any planning and redevelopment decision-making necessary for public housing in New Orleans must include, engage and be informed by representatives of all people affected.

- Step up enforcement of all applicable human rights laws. The Fair Housing Act of 1968 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibit housing practices and publicly subsidized rebuilding efforts, respectively, that have a racially discriminatory purpose or effect. HUD and the U.S. Department of Justice should immediately direct enforcement resources to the Gulf Coast region and the Katrina diaspora, to ensure that all displaced people enjoy an equal right to housing opportunity.

In the longer term, significant investment is needed in government systems that create new affordable housing that is equally accessible to all of the people of the Gulf Coast region. Recommendations include:

- Require a Housing Opportunity Impact Statement as a condition of public support for future rebuilding efforts. Under this requirement, federal, state and local agencies should call upon developers, contractors, and others involved in the reconstruction process to demonstrate—based on available data—that planned redevelopment will ensure poor people and people of color equal access to safe, clean, affordable housing that is accessible by roads and public transportation to good jobs, quality schools, safe daycare, and nutritious food. The requirement should be coupled with incentives for the development of mixed income neighborhoods and ensure that environmental protections are respected in all communities. And it should afford local residents a meaningful voice in the planning and decision process. Existing federal laws, including the Fair Housing Act of 1968 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 authorize, and may require, this approach.

- Fully fund the repair and rehabilitation of privately owned housing stock, for both immediate and long term housing needs, and for new construction for long term housing needs. Funds should be provided through the HOME program of grants to states and localities, which has income targeting and long term affordability requirements that would assure that the homes repaired with public funds would not be subject to speculative increases as the recovery proceeds. (The Community Development Block Grant) program is not bound by such rules. Funds should be prioritized to affected areas and jurisdictions with large numbers of evacuees and for rental housing affordable to extremely low-income households. Some waivers of existing statutory requirements will be needed to facilitate rapid deployment of funds.46

- Adequately support and enable HUD’s Flexible Subsidy Program to provide no and low- interest loans to damaged HUD project- based housing stock. HUD estimates that there is a $200 million gap between what is required to repair all damaged units and what insurance payments will cover. This program was successfully used to repair HUD-assisted housing damaged in the Northridge earthquake.

- Fully fund 13,500 new project- based vouchers to be tied to the production of new rental units developed through new Gulf Opportunity Zone ( GoZone) Low Income Housing Tax Credits ( LIHTC). These vouchers would enable the states to make roughly 25% of the units built with their additional allocations of LIHTCs affordable to the lowest-income households, including working poor families, senior citizens and people with disabilities. This provision was included in the Senate version of the 2006 Emergency Supplemental Appropriations bill, but was dropped during conference committee negotiations.

- Promote homeownership among low-income families through down- payment- assistance programs, and rent- to- own programs. The American Dream Downpayment Initiative signed by President Bush in 2003, and expansion of the LouLease (Louisiana’s rent-to-own program) could assist families that had uninsured homes destroyed by the hurricane to return to ownership.47

- Extend the deadline by which all new projects built using GoZone, Rita GoZone and Wilma GoZone LIHTCs are placed in service to December of 2010. Creating more affordable housing stock and sustainable communities by extending the LIHTC would improve the ability of the tax credit to decrease concentrated poverty—and expanding HOPE VI, the only major federal program dedicated solely to the creation of affordable housing communities. Extend through 2009 the bonus depreciation eligibility deadline for residential rental property in the allotment of GoZone, Rita GoZone and Wilma GoZone LIHTCs. Provide a rules waiver allowing states to increase the level of tax credit subsidy per development.

- Reimburse federal housing and homeless programs that responded to the needs of evacuees using resources already in short supply. Soon after the hurricane, Local Housing Authorities (LHAs) and other agencies responded to the needs of displaced households with existing resources. In most cases, disaster victims displaced people with critical housing needs who were waiting for assistance before the hurricanes. LHAs and other agencies must be reimbursed for their disaster response costs, even in states that were not declared federal disaster areas.

Finally, because many of the housing problems revealed by Katrina flow from national trends, we call for a new national vision that expands housing opportunity for all Americans. Our long-term recommendations include scaling up many of the reforms described above to reach Americans drowning on dry land without access to safe, fair, and affordable housing. In particular, inclusionary zoning that encourages mixed-income housing is an important tool with a proven track record. In addition, the Home Mortgage Data Reporting Act should be expanded, and the Federal Reserve Bank should step up its fair lending oversight. When tax incentives and other indirect encouragement fail, state and federal governments must subsidize the development of new affordable housing.

Conclusion

In a country in which we are increasingly interconnected, we can’t afford not to invest in opportunity for all our residents. Ensuring housing opportunity for all is an investment in the prosperity of our nation that provides returns for many years to come.

Acknowledgements

While this report includes new analysis and policy recommendations, it relies heavily on research conducted by a range of scholars, institutions, and agencies over the course of the last twelve months. Without that foundation of knowledge and expertise, our findings and recommendations would not be possible. In particular, we wish to acknowledge researchers and analysts at the Advancement Project, the Brookings Institution, the Center for Social Inclusion, the Economic Policy Institute, PolicyLink, and the Poverty and Race Research Action Council.

Finally, and most importantly, we thank and honor the people of the Gulf Coast who have endured so much yet continue to pursue the promise of opportunity for all.

Notes:

1. M. Hunter, “Deaths of Evacuees Push Toll to 1,577,” The Times-Picayune, May 19, 2006; Congressional Research Service, “Hurricane Katrina: Social-Demographic Characteristics of Impacted Areas,” November 4, 2005.

2. The Brookings Institution Metropolitan Policy Program, “New Orleans After the Storm: Lessons from the Past, a Plan for the Future,” October 2005.

3. Louisiana Recovery Authority, “By the Numbers,” April 10, 2006.

4. Ibid.

5. The right of internally displaced people to return to their communities is recognized internationally, as in the United Nations’ Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, to which the U.S. has looked in responding to disasters in other parts of the world. These guidelines call for equal and adequate access to resettlement, housing, education, and health care for affected people and communities, whatever their race or ethnicity. See U.S. Agency for International Development, “USAID Assistance to Internally Displaced Persons Policy,” October 2004.

6. S.J. Popkin, M.A. Turner, and M. Bert, “Rebuilding Affordable Housing in New Orleans: The Challenge of Creating Inclusive Communities,” The Urban Institute, January 2006.

7. Ibid.

8. Greater New Orleans Community Data Center, “Orleans Parish: Housing and Housing Costs,” July 2006.

9. In Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Louisiana’s segregated railway-car laws.

10. 334 US 1 (1948).

11. 347 US 483 (1954).

12. Hicks v. Weaver, 302 F. Supp. 619 (E.D. La. 1969).

13. Hicks v. Weaver, 623.

14. J. Logan, “Ethnic Diversity Grows, Neighborhood Integration Lags Behind,” Lewis Mumford Center for Comparative Urban and Regional Research, University of Albany, December 18, 2001.

15. U.S. Census Bureau, “Table 5-4: Residential Segregation for Blacks or African Americans in Large Metropolitan Areas: 1980, 1990, and 2000,” n.d.

16. Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity, The Ohio State University, “Mid-Term Report: New Orleans Opportunity Mapping: An Analytical Tool to Aid Redevelopment,” February 1, 2006.

17. The Brookings Institution Metropolitan Policy Program, “Katrina’s Window: Confronting Concentrated Poverty across America,” executive summary, October 2005.

18. The Brookings Institution, “New Orleans After the Storm.”

19. Congressional Research Service, “Hurricane Katrina: Social-Demographic Characteristics of Impacted Areas.”

20. Gwen Filosa, “Protesters Take Plight to the Avenue: Scarce Public Housing Has People Upset,” The Times-Picayune, June 18, 2006.

21. Louisiana Recovery Authority, “The Road Home Housing Programs Action Plan Amendment for Disaster Recovery Funds,” n.d.

22. A. Liu, M. Fellowes, and M. Mabanta, “Katrina Index: Tracking Variables of Post-Katrina Recovery,” The Brookings Institution, July 12, 2006.

23. The National Alliance to Restore Opportunity to the Gulf Coast and Displaced Persons, “The Aftermath of Katrina and Rita: The Human Tragedy Inflicted on the Gulf Coast,” n.d.

24. The National Alliance to Restore Opportunity to the Gulf Coast and Displaced Persons, “Progress in the Gulf Coast: 10 Months Later,” n.d.

25. Advancement Project, New Orleans Worker Justice Coalition, and the National Immigration Law Center, “And Injustice for All: Workers’ Lives in the Reconstruction of New Orleans,” July 2006.

26. Housing Authority of New Orleans, “Post-Katrina Frequently Asked Questions,” n.d.

27. Ibid. Before Hurricane Katrina, the Housing Authority of New Orleans helped house about 14,000 families: 5,100 occupied public housing, and 9,000 families received Section 8 vouchers. See Michelle Roberts, “HUD Plans to Demolish Some of New Orleans’ Largest Housing Projects,” The Associated Press, June 14, 2005.

28. J. Logan, “The Impact of Katrina: Race and Class in Storm-Damaged Neighborhoods,” Spatial Structures in the Social Sciences, Brown University, January 2006.

29. Greater New Orleans Community Data Center, “Current Housing Unit Damage Estimates: Hurricanes Katrina, Rita and Wilma,” February 12, 2006, revised April 7, 2006.

30. Liu et al., “Katrina Index.”

31. J. Moses, “Katrina’s Trailer Exiles” The Washington Post, June 17, 2006.

32. National Fair Housing Alliance, “No Home for the Holidays: Report on Housing Discrimination against Hurricane Katrina Survivors,” December 20, 2005.

33. M. Fellowes et al., “The State of New Orleans: An Update,” New York Times, July 5, 2006.

34. Louisiana Recovery Authority, “By the Numbers,” 2006.

35. Fellowes et al., “The State of New Orleans.”

36. Louisiana Recovery Authority, “By The Numbers.”

37. National Alliance to Restore Opportunity, “The Aftermath of Katrina and Rita.”

38. Economic Policy Institute, “Economic Snapshot,” November 9, 2005.

39. The Opportunity Agenda, The State of Opportunity in America, February 2006.

40. Ibid.

41. National Community Reinvestment Coalition, The Opportunity Agenda, and Poverty and Race Research Action Council, “Homeownership and Wealth Building Impeded,” April 2006.

42. W. Fischer and B. Sard, “Housing Needs of Many Low-Income Hurricane Evacuees Are Not Being Adequately Addressed,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 27, 2006.

43. Ibid.

44. Ibid.

45. Ibid.

46. Popkin, Turner, and Bert, “Rebuilding Affordable Housing in New Orleans.”

47. Fischer and Sard, “Housing Needs of Many Low-Income Hurricane Evacuees.”