Sexual Violence, The #MeToo Movement, and Narrative Shift

The prevalence of sexual assault in the United States, defined broadly to include not only acts of violence, but also sexual harassment and intimidation, has been the subject of media coverage and on the public policy agenda in fits and starts for more than forty years. In the past, scandals have erupted in the military, on campuses, within the priesthood, or involving a very public figure and generated media attention. Sometimes prosecutions or incremental policy reforms follow, and then the problem drops from public view until the next flare-up occurs. In late 2017, the #MeToo Movement suddenly burst onto the national stage and dominated the news cycle for weeks on end. Millions of survivors of sexual violence, not only in the United States but around the globe, took to social media and spoke out, disclosing the harms and trauma they had experienced, and within a short time, hundreds of abusers, most of them men, were toppled from positions of power. Nothing like this had ever happened before.

Today, a new movement under the leadership of survivor advocates and activists is growing in size and influence. This increased awareness and activism suggests that this time, the issue may not simply recede into the hidden corners of society where it has traditionally lurked, out of sight and out of mind for people without a direct reference point or experience. This time, a shift in the overarching narrative about sexual violence in America, driven by the survivors themselves, has the potential to bring about real institutional and behavioral change. This case study explores how the #MeToo Movement is shifting long-dominant narratives that have contributed to the societal acceptance of high levels of sexual violence in this country.

METHODOLOGY

INTERVIEWEES

- Denise Beek, Chief Communications Officer, “me too”

- Moira O’Neil, PhD, Vice President of Research and Interpretation, FrameWorks Institute

- Kenyora Parham, Executive Director, End Rape on Campus Nancy Parrish, Founder and CEO, Protect Our Defenders

- Juhu Thukral, Founder + Principal, Apsara Projects LLC

- Brooke Foucault Welles, PhD, Associate Professor in the Department of Communication Studies, Northeastern University

- Fatima Goss Graves, President and CEO of the National Women’s Law Center

OTHER SOURCES CONSULTED

- Maria Bevacqua, Rape on the Public Agenda: Feminism and the Politics of Sexual Assault. Northeastern University Press, 2000

- Ryan J. Gallagher, Elizabeth Stowell, Andrea G. Parker, and Brooke F. Welles. Reclaiming Stigmatized Narratives: The Networked Disclosure Landscape of #metoo. SocArXiv. May 24, 2019

- Carly Gieseler, The Voices of #MeToo: From Grassroots Activism to a Viral Roar. Bowman & Littlefield, 2019

- Kate Harding, Asking For It: The Alarming Rise of Rape Culture—and What We Can Do About It. Perseus Books Group, 2015

- Sarah J. Jackson, Moya Bailey, and Brooke Foucault Welles, #Hashtag Activism: Networks of Race and Gender Justice. The MIT Press, 2020

- Moira O’Neil and Pamela Morgan, American Perceptions of Sexual Violence. FrameWorks Institute, 2010

- Katie Thomson, “Social Media Activism and the #MeToo Movement,” Medium, June 12, 2018

MEDIA AND SOCAL MEDIA RESEARCH

To identify media trends, we developed a series of search terms and used the LexisNexis database, which provides access to more than 40,000 sources, including up-to-date and archived news. For social media trends, we utilized the social listening tool Brandwatch, a leading social media analytics software that aggregates publicly available social media data.

THE SIZE OF THE PROBLEM

The fact that the prevalence of sexual assault in the United States is high is not open to controversy. According to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program, the rate of rape increased by 15 percent between 2014 and 2018.[2] Since rape is a crime that is greatly underreported, the actual numbers are likely much higher.

The numbers from institutions that are required by law to collect such data are also sobering. In the military, 6.2 percent of active-duty women reported a violent sexual assault in 2018, and 24.2 percent reported an experience of sexual harassment. Again, the actual numbers are much higher. The military estimates that only one out of every three servicewomen who experience sexual assault files a report.[3] On college campuses, a 2019 survey of more than 181,000 students found that one in four undergraduate women from 33 large universities had experienced sexual assault while they were students.[4] Compounding the problem is the fact that so few individuals are held accountable for their actions. According to World Population Review, only 9 percent of rapists in the United States get prosecuted and only 3 percent of rapists will spend a day in prison. Of rapists in the United States, 97 percent walk free.[5]

Sexual harassment in the workplace is also extremely common in the United States. Surveys show that approximately 30 percent of women have experienced such harassment.[6] In an ABC News/Washington Post survey conducted Oct. 12–15, 2017, after the Weinstein revelations became public but before #MeToo, 54 percent of women said they had received unwanted sexual advances from a man that they felt were inappropriate whether or not those advances were work-related; 30 percent said this had happened to them at work.[7] In an NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll conducted Nov. 13–15, 2017, 35 percent of women said they have personally experienced sexual harassment or abuse from someone in the workplace.[8]

BACKGROUND: THE ANTI-RAPE MOVEMENT OF THE 1970S

The rise of the women’s movement in the mid-1960s put sexual violence on the public policy agenda for the first time. Until feminists proclaimed that “the personal is political,” any public discussion of rape and other forms of sexual assault was considered taboo, hidden behind a veil of secrecy, shame, and myth. Susan Brownmiller, whose groundbreaking 1975 book Against Our Will would articulate a feminist analysis of rape, admitted that like many other women of that era, she had perceived it as “a sex crime, a product of a diseased, deranged mind” or as a false charge made by a white woman against a Black man. She wrote that she once believed women in the movement “had nothing in common with rape victims.”

That view began to change with the proliferation of consciousness-raising groups throughout the country. In these intimate and safe settings, women began to reveal experiences from their own lives that they had long kept hidden because of fear and shame. Through this process they discovered that problems they thought were individual actually reflected common conditions faced by all women—including unwanted sexual contact. In January 1971, the New York Radical Feminists held the first public event in the United States at which women spoke about their experiences of being raped. The speak-out was held in a small church in midtown Manhattan. With more than 300 women in attendance, forty spoke about their assault both at the hands of the rapist and then again at the hands of the justice system. The result of this event was the birth of the anti-rape movement and a challenge to the “rape myths” that were embedded in American culture.

ANTI-RAPE IDEOLOGY

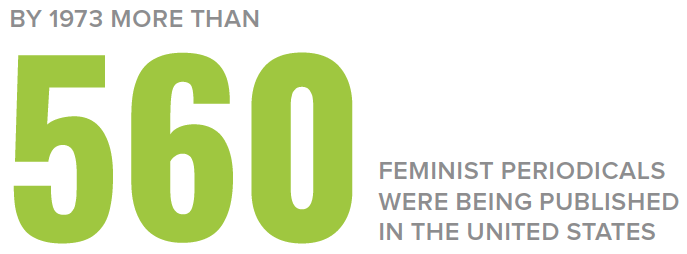

Throughout the decade of the 1970s feminists developed an analysis that would challenge the most common myths about rape, which they defined as any unwanted sexual contact. They organized more speak-outs across the country to demonstrate that rape was not an isolated or uncommon event. They published hugely influential books and articles such as Kate Millett’s Sexual Politics, Susan Griffin’s Rape—The All American Crime, Barbara Mehrhof and Pamela Kearon’s Rape: An Act of Terror, and Shulamith Firestone’s The Dialectic of Sex. At its core, anti-rape ideology insisted that rape was about violence, not sex, providing feminists with a new framework that removed all blame from victims whose claims were viewed as fully credible. The threat of sexual violence perpetuated male dominance and patriarchy, and eliminating rape would require transforming the gendered social arrangements that pervaded American culture. These ideas were then disseminated through the growing network of journals and newspapers, both mainstream and underground. By 1973 more than 560 feminist periodicals were being published in the United States, such as Everywoman (Los Angeles), Second Wave (Cambridge), Off Our Back (Washington, D.C.), Rat (New York), and Big Mama Rag (Denver).

ANTI-RAPE ORGANIZING

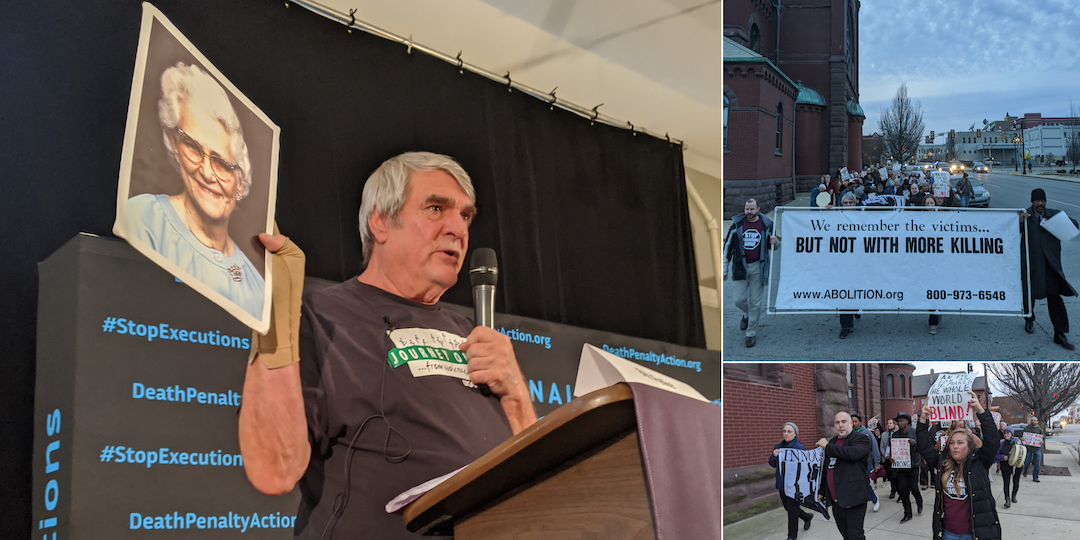

Armed with a shared consciousness and set of political goals, feminists created an array of organizations to agitate for policy reform and provide services to victims. They took many forms. Self-defense groups trained women in martial arts and other skills to combat violence against them and instill a sense of self-reliance. The first rape crisis center, designed to provide direct services to sexual assault victims, was founded in 1972 in Washington, D.C. Rape crisis centers cropped up throughout the country, aided by the Washington, D.C., center’s widely distributed pamphlet, “How to Start a Rape Crisis Center.” At its 1973 national conference, the National Organization of Women, the nation’s largest women’s rights organization, adopted Resolution 148, creating the organization’s National Rape Task Force. And in mid-1974 the Feminist Alliance Against Rape (FAAR) was founded to serve as “an autonomous organization of community-based and feminist-controlled anti-rape projects.” In 1975, “Take back the night” became a rallying cry when the first march calling for an end to sexual violence took place in Philadelphia. The year 1978 saw the founding of the National Coalition Against Sexual Assault (NCASA), whose main goal was “to end sexual violence and rape in our society.”

By the mid-1970s the anti-rape movement had achieved some significant policy victories. A major focus was law reform. The humiliation and dismissiveness faced by victims brave enough to report their assaults to the police and to press for criminal prosecution and accountability were characterized as simply another rape. Rape laws themselves were seen as biased toward the defendant because they required standards of proof that were almost impossible to meet.[9] In some states, for example, the law required “corroborative evidence” of non-consent before a prosecutor would bring a case; the victim’s testimony, no matter how compelling, was never enough. In New York the Anti-Rape Squad organized an “Assault on the State Legislature to Repeal the Corroboration Requirement,” and a coalition of feminist groups campaigned for its full repeal with legislative testimony, press conferences, and rallies. In 1974, the campaign succeeded, demonstrating the movement’s ability to change entrenched law and policy. Other reforms followed.

THE MOVEMENT’S LIMITATIONS

RAPE AND RACE

The feminist movement of the 1970s and beyond has long been criticized for being predominantly white and middle-class and for not addressing the needs and concerns of poor women, Black women, and other women of color. Although there were Black women who participated in and led the anti-rape movement, critics argued that the movement did not adequately analyze or act upon the complex intersection of rape and race in this country. Obviously, Black men accused of raping white women, especially in the South, did not enjoy the deference the legal system paid to white male defendants. And the movement’s assertion that all women were equally subject to rape and its aftermath was rejected by Black women and other women of color who never expected fair treatment from the criminal justice system. Scholar and activist bell hooks explained the racial hierarchy that applied in how rape was treated in her 1981 book, Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism:

As far back as slavery, white people established a social hierarchy based on race and sex that ranked white men first, white women second, though sometimes equal to black men, who are ranked third, and black women last. What this means in terms of the sexual politics of rape is that if one white woman is raped by a black man, it is seen as more important, more significant than if thousands of black women are raped by one white man. Most Americans, and that includes black people, acknowledge and accept this hierarchy; they have internalized it either consciously or unconsciously. And for this reason, all through American history, black male rape of white women has attracted much more attention and is seen as much more significant than rape of black women by either white or black men.

RAPE AND GENDER

The exclusive focus on cisgender women led the anti-rape movement to ignore other groups of people who were preyed upon sexually. A survey of close to 30,000 transgender people in the United States conducted in 2015 by the National Center for Transgender Equality showed that nearly half (47%) of respondents were sexually assaulted at some point in their lifetime and one in ten (10%) were sexually assaulted in the past year. In communities of color, these numbers are higher: 53% of Black respondents were sexually assaulted in their lifetime and 13% were sexually assaulted in the past year.[10] Although such data were not collected in the 1970s before the advent of a transgender rights movement, there is every reason to believe that the statistics were equally disturbing. Sexual violence against men and boys was also unexamined and discounted as an issue by the early anti-rape movement.

RAPE CULTURE

In spite of its many achievements, the anti-rape movement did not dislodge what came to be called the country’s “rape culture,” a term first coined by the New York Radical Feminist Collective in 1974 in Rape: The First Sourcebook for Women. It is a term in much use today in discussions about the continuing prevalence of sexual assaults. In the words of feminist journalist Amanda Taub, rape culture is: “A culture in which sexual violence is treated as the norm and victims are blamed for their own assaults. It’s not just about sexual violence itself, but about cultural norms and institutions that protect rapists, promote impunity, shame victims, and demand that women make unreasonable sacrifices to avoid sexual assault” (“Rape Culture Isn’t a Myth,” Vox, Dec. 15, 2014). It leads to victim-blaming (“slutshaming”), stigmatization of the victim, and the perpetuation of sexist attitudes and leniency for the perpetrator. This in turn discourages survivors from speaking out and so, until recently, created a culture of silence.

According to Women’s Studies Professor Maria Bevacqua, who authored Rape on the Public Agenda (Northeastern University Press, 2000), by the time of Ronald Reagan’s ascendance to the presidency in 1981 the anti-rape movement had “reached the stage of abeyance. Organizations were operating in a ‘holding pattern,’ devoting energy to maintaining hard-won gains rather than undertaking new challenges to the established order.” Rape was no longer the hot issue it had been in the 1970s. In many ways, the existing narratives were left intact.

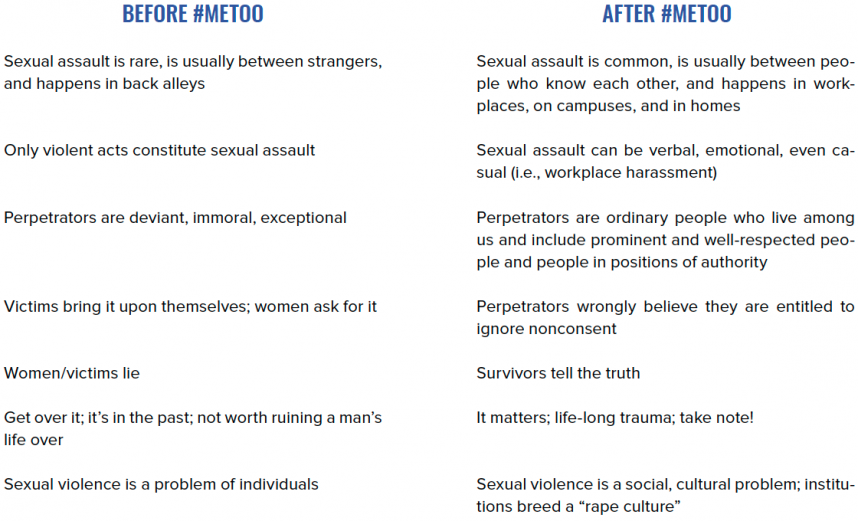

THE SEXUAL ASSAULT NARRATIVES BEFORE #METOO

In 2010 FrameWorks Institute, a progressive communications think tank, published a study commissioned by the National Sexual Violence Resource Center (NSVRC). Titled, “American Perceptions of Sexual Violence,” it reported findings based on a series of interviews with both experts and “average Americans.” The experts, who were identified by the NSVRC, were practitioners working in the field of sexual violence and its prevention. The average Americans were recruited in Los Angeles and Philadelphia by a professional marketing firm to “represent variation along the domains of ethnicity, gender, age, educational background and political ideology.”

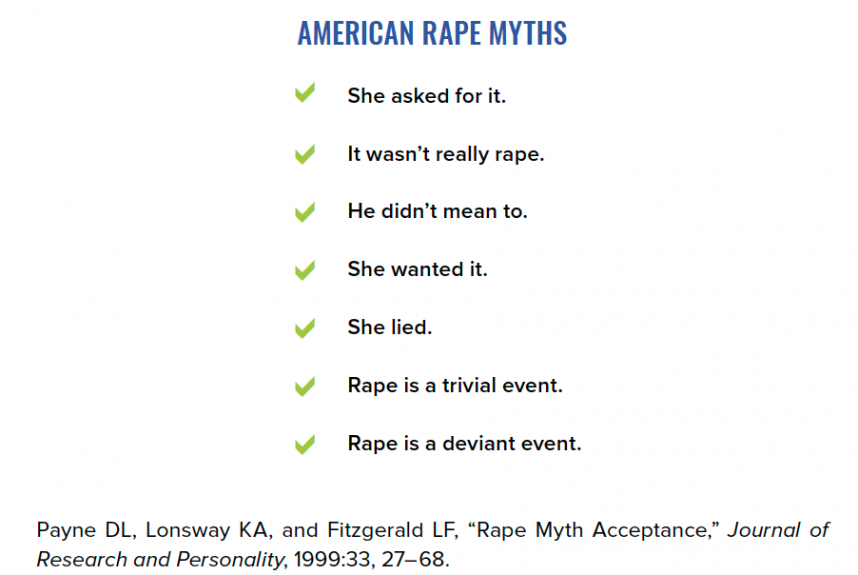

FrameWorks found that there were substantial gaps in understanding between the two groups. The experts emphasized that sexual violence impacts all parts of society and that it happens more frequently than most members of the public realize. They explained that perpetrators are “everyday people” who are known and even loved by their victims. According to the experts, one of the primary causes of sexual violence is a culture of unequal power relationships seen to “give people permission” to dehumanize others. In contrast, the nonexperts regarded sexual predators as mentally disturbed or immoral individuals who were molded by “bad upbringing” by their parents. They fell back on the assumption that people are responsible for ensuring their own safety and talked about girls and women needing to “think about” and “choose” the kinds of clothes they wear, the places they go, behaviors such as walking alone, and the company they keep. In these responses are the telltale signs of the acceptance of “rape myths.”

In 1980, psychologist Martha M. Burt published her groundbreaking research on the prevalence of rape myths and their influence on interpersonal violence. She defined rape myths as “prejudicial, stereotyped, or false beliefs about rape, rape victims, and rapists.” Her hypothesis was that the acceptance of rape myths predisposed individuals to perpetrate sexual assaults. Based on the administration of a Rape Myth Acceptance Scale (RMAS) of her own devising to 600 randomly selected adults, she found that many Americans believed in rape myths. For example, more than half of the individuals agreed that “a woman who goes to the home or apartment of a man” on the first date “implies she is willing to have sex” and that in the majority of rapes “the victim was promiscuous or had a bad reputation.” More than half of Burt’s respondents agreed that 50 percent or more of reported rapes were reported “only because the woman was trying to get back at a man” or “trying to cover up an illegitimate pregnancy.” Burt posited that rape myth acceptance was the link to the prevalence of rape and sexual assault in the United States. Her RMAS is still used today by researchers.

Since that time, a body of interdisciplinary social science research has documented that rape myth acceptance is still pervasive in American society. In a leading journal article surveying the field, the authors conclude:

- “Rape myths, which include elements of victim blame, perpetrator absolution, and minimization or rationalization of sexual violence, perpetuate sexual violence against women. Indeed, research has documented that men’s engagement in sexual violence is predicted by rape myth acceptance…rape myths, despite their falsehood, are endorsed by a substantial segment of the population and permeate legal, media, and religious institutions.”[11]

- Recent examples of rape myths in action are legion, but here are just a few:

· The dismissal of then-candidate Trump’s boast about his own sexually assaultive behavior in the Access Hollywood recording as “just locker room talk.”

· Rep. Todd Akin’s (R-MO) claim in 2012 in a debate over abortion rights that “[i]f it’s a legitimate rape, the female body has a way of shutting that whole thing down.”

· A 2014 Forbes.com article by columnist Bill Frezza titled, “Drunk Female Guests Are the Gravest Threat to Fraternities.”

· Fraternity pledges at Yale chanting “No means yes, yes means anal.”

· A judge lectures the victim of a sexual groping incident: “If you wouldn’t have been there that night, none of this would have happened to you…. When you blame others you give up your power to change.”[12]

Popular culture transmits and reinforces rape myths through song lyrics, television shows, movies, and, of course, pornography, especially when it depicts violence. Rick Ross raps: “Put molly all in her champagne, she ain’t even know it, I took her home and I enjoyed that, she ain’t even know it.” The role of popular media in reinforcing rape myths has been the subject of research.One study of the effects of certain video games concluded that “a video game depicting sexual objectification of women and violence against women resulted in statistically significant increased rape myths acceptance (rape-supportive attitudes) for male study participants but not for female participants.”[13] A study of the content of popular comic books found that they reinforced rape myths: “Rape myths that were supported included a number of rape survivor, rape perpetrator, and victim blaming myths.”[14]

A LITANY OF SCANDALS, 1991-2017

The recurring sex scandals that have rocked the nation over the past 30 years are compelling evidence of the persistent influence of rape myths and rape culture—scandals that have been vigorously reported in the media, to be followed by some reforms, and then pushed into the background. This is the backdrop for what was to become the #MeToo Movement.

SEPTEMBER 1991: The Tailhook Scandal

The Tailhook Association, a fraternal organization for members of the military, held its annual convention at the Las Vegas Hilton. One night, a “gauntlet” of male military officers groped, molested, or committed other sexual or physical assaults and harassment on women who walked through the hotel’s third floor hallway. Ultimately, more than one hundred U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps aviation officers were accused of sexually assaulting eighty-three women and seven men. An investigation by the Department of Defense Inspector General’s Office led to approximately forty naval and Marine officers receiving nonjudicial punishment for “conduct unbecoming an officer.” Three officers were taken to courts-martial, but their cases were dismissed. No officers were disciplined for the alleged sexual assaults.

OCTOBER 1991: The Anita Hill Hearings

In 3 days of televised hearings before the U.S. Senate, law professor Anita Hill described the crude and relentless sexual harassment she had experienced during the time she worked under the supervision of Clarence Thomas, who had been nominated to serve on the Supreme Court. The all-male, all-white Senate Judiciary Committee’s dismissive and offensive treatment of Ms. Hill became legendary. Thomas was elevated to the Supreme Court.

NOVEMBER 1996: The Aberdeen Sex Scandal

The Army opened an investigation into multiple sexual assaults at the Army Ordnance Center and Schools on Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland after a female recruit reported an assault. Referred to as “the Army’s Tailhook” and “the Aberdeen rape ring,” twelve drill instructors were charged with sex crimes, including one instructor who was eventually convicted of raping six female trainees. Ultimately, four were sentenced to prison, while eight others were discharged or received nonjudicial punishment.

JANUARY 1998: The Bill Clinton Sex Scandal

The legal and political fallout from the President’s affair with his 24-year-old intern, Monica Lewinsky, would dominate the news for much of the year. Although portrayed as a consensual relationship, Clinton’s behavior and his repeated claims that he “had not had sexual relations with that woman” were emblematic of the unequal power relationships that exist in the workplace and how powerful men can prey upon their subordinates with relative impunity.

JANUARY 2002:

The Boston Globe broke the story about sexual abuse of boys committed by priest John J. Geoghan and the coverup by the Catholic diocese. This revelation was followed by the public exposure of numerous priests in the United States and around the world who had molested children under their care and supervision.

JANUARY 2003: The Colorado Springs Air Force Academy Scandal

An anonymous e-mail to the Air Force chief of staff, members of Congress, and the media alleging that there was a serious sexual assault problem at the Academy that was being ignored by the institution’s leadership ignited an investigation by the Air Force’s inspector general. The investigation revealed that 12 percent of the women who graduated from the Academy in 2003 reported that they were victims of rape or attempted rape. A survey of 579 women at the academy (out of a total enrollment of 659) found that 70 percent had been the victims of sexual harassment, of which 22 percent said they experienced “pressure for sexual favors.”

NOVEMBER 2011: Pennsylvania State University Scandal

The Penn State scandal broke when Jerry Sandusky, an assistant coach for the university’s football team, was charged with 52 counts of child molestation over a period of 15 years. Three Penn State officials were charged with perjury, obstruction of justice, and failure to report suspected child abuse. Sandusky was ultimately convicted on forty-five counts of child sexual abuse and was sentenced to a minimum of 30 years and a maximum of 60 years in prison.

MAY 2011: Delta Kappa Epsilon Suspension

The Yale University chapter of the DKE fraternity was suspended for 5 years after pledges marched through the freshman residential quadrangle chanting “No means yes, yes means anal,” “Fucking sluts!” and “I fuck dead women and fill them with my semen” and for carrying a sign that read “We love Yale sluts.”

FEBRUARY 2014: University of Michigan Cover-Up

In 2009 a student accused an up-and-coming football kicker, Brendan Gibbons, of rape. She reported the incident to the resident advisor of her dorm, a university housing security officer, campus police, and Ann Arbor police, but nothing was done. Four years later it was revealed that the university had engaged in a cover-up so that Gibbons could continue to play for the school team.

APRIL 2014: Complaints Against Columbia University

Twenty-three Columbia University students filed complaints with the federal Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights charging systematic mishandling of sexual assault claims and mistreatment of victims by the university. They contended that campus counseling services pressured them not to report sexual assault or harassment and that perpetrators were rarely expelled. One of the survivors, Emma Sulkowicz, generated media attention by carrying around a mattress on campus in protest.

JULY 2014: University of Connecticut Settles Case

It was announced that the University of Connecticut would pay $1.28 million to settle a lawsuit filed by five students who charged that the university had treated their claims of sexual assault and harassment with indifference. The university denied any wrongdoing. None of the men accused in the complaint faced criminal charges. One accused rapist was expelled, but his expulsion was appealed and he was permitted back on campus.

NOVEMBER 2014: Bill Cosby Survivors Speak Out

After stand-up comedian Hannibal Buress called out Cosby as a rapist during a Philadelphia performance, numerous women describe being drugged and raped by him. Eventually, nearly sixty women accused him of sexual assault over a period of 30 years. The criminal investigation, trials, and conviction in Pennsylvania generated enormous press coverage.

OCTOBER 2016: Access Hollywood Tape

On October 7, during the run-up to the presidential election, The Washington Post published a video and accompanying article about candidate Donald Trump’s comments to Access Hollywood TV show host Billy Bush in 2005. In the video, Trump described his attempt to seduce a married woman and indicated he might start kissing a woman that he and Bush were about to meet. He added, “I don’t even wait. And when you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything…. Grab them by the pussy. You can do anything.”

APRIL 1, 2017: Bill O’Reilly Settlements

The New York Times broke the story that Fox News had reached settlements with six women who had worked for him or appeared on his show totaling $45 million and dating to 2002. The news came out in spite of the nondisclosure agreements each woman was compelled to sign. O’Reilly was ousted from Fox News.

OCTOBER 5, 2017: The Outing of Harvey Weinstein

The New York Times ran the story investigated by reporters Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey, “Harvey Weinstein Paid Off Sexual Harassment Accusers for Decades.” It included quotes from several of his victims, including actress Ashley Judd, and described how his misconduct had been tolerated and kept hidden by his company’s inner circle. Two days later he was fired by his own company.

OCTOBER 10, 2017: The Weinstein Scandal Deepens

The New Yorker published Ronan Farrow’s investigative report, “From Aggressive Overtures to Sexual Assault: Harvey Weinstein’s Accusers Tell Their Stories.” Based on interviews with thirteen women who Weinstein had harassed or assaulted, the article described how Weinstein and his associates used nondisclosure agreements, payoffs, and legal threats to suppress their accounts.

OCTOBER 15, 2017: #MeToo

In a tweet titled Me Too, actress Alyssa Milano wrote: Suggested by a friend: “If all the women who have been sexually harassed or assaulted wrote ‘Me too.’ as a status, we might give people a sense of the magnitude of the problem.” By 3:21 p.m. that day, 90,400 people were “talking about this.”

THE ORIGINS OF ME TOO

The scandals that erupted during the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s in hotspots like the military and college campuses or that involved well-known perpetrators received extensive media coverage and led to some ameliorative policies and actions. In 1994 the Violence Against Women Act was signed into law by President Bill Clinton, providing federal funding for investigation and prosecution of crimes against women. In 2004 the Congressional Women’s Caucus held a hearing on the military’s handling of sexual assault cases, which led to the introduction of the Military Justice Improvement Act. And in 2014, President Obama formed the White House Task Force to Protect Students from Sexual Assault. But still hidden from view and unaddressed was another scandal: the large number of sexual assaults against women and girls of color in low-wealth communities and the desperate lack of resources and services for the survivors of those assaults. Enter Tarana Burke.

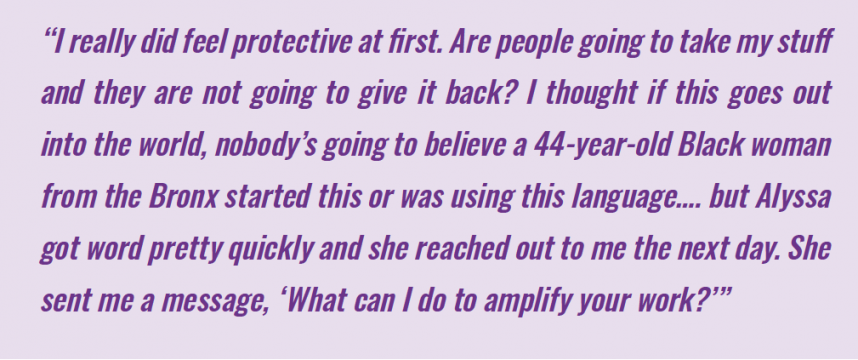

Tarana Burke is an activist from the Bronx, New York who is herself a survivor of sexual violence. In 2003 she began working with an afterschool program for Black girls aged 12 to 18 in Philadelphia and was struck by how many of them were traumatized by sexual assaults they had experienced. In her own words, she “set out to bring healing to the Black and Brown girls in my community while raising awareness about the trauma they faced, and the lack of protections made available to them.” In 2006 she founded a nonprofit organization called Me Too. Burke’s goal was to center survivors in their own healing journeys, to create community, and work “to interrupt sexual violence in a real way.”

On the day of the Milano tweet Burke began receiving phone calls and e-mails from friends telling her that the MeToo hashtag was all over social media. “I didn’t really tweet; I wasn’t a tweeter.” Burke said. In an interview with Teen Vogue she described her initial reaction:

This fortuitous confluence of a celebrity-driven social media campaign with an existing social justice–oriented, Black-led movement would be the catalyst for shifting the narrative about sexual violence in America.

#METOO

The Milano tweet opened the floodgates and demonstrated, for the first time, the force and power social media was able to inject into the framing of sexual violence. The phrase “Me too” was used more than 200,000 times by the end of the first day and had been tweeted more than 500,000 times by the next day, October 16. On Facebook, the hashtag was used by more than 4.7 million people in 12 million posts during the first 24 hours. By October 17 it had become headline news all over the country:

- #MeToo Floods Social Media With Stories of Harassment and Assault, New York Times

- Mich. women call out sexual harassment, Detroit Free Press

- #MeToo Campaign Empowers Women in Pittsburgh to Join Movement, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

- ‘Me too’ campaign gains ground as safe space for stories of harassment, The San Francisco Chronicle

- Oklahomans say #MeToo, The Oklahoman

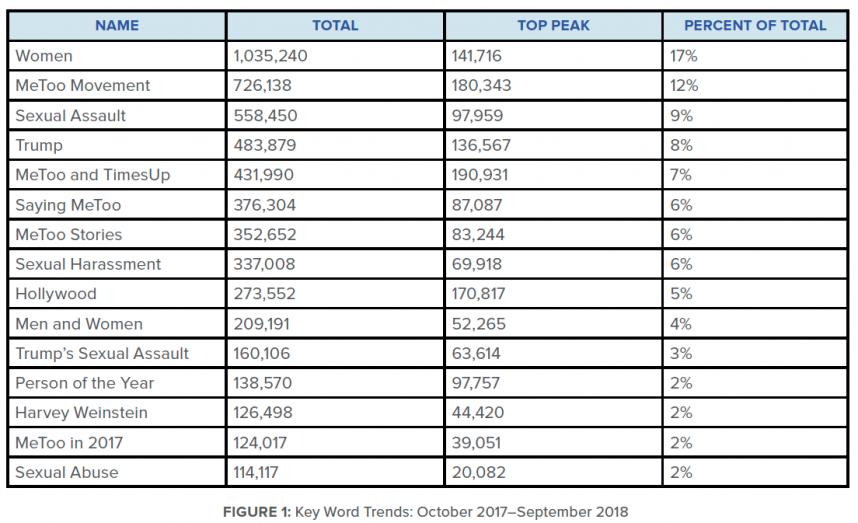

By the end of the first week, 1,595,453 tweets were posted, and the numbers continued to soar. The hashtag went global, with tweets from 85 countries posted by October 27. As noted in a 2018 report produced by The Opportunity Agenda, between October 2017 and September 30, 2018, more than 27 million online posts with specific references to “Me-Too,” “me too,” “me too movement,” and other variants were generated (The Opportunity Agenda, 2018). The vast majority of content in this first year of widespread online engagement focused on Harvey Weinstein, and sexual violence within the entertainment industry more broadly. An exploration of key phrases generated between October 2017 and September 2018 shows a strong association between revelations of sexual harassment experienced by high-profile women within the entertainment industry and overall discourse related to #MeToo (Figure 1).

Despite this early focus on the culture of sexual violence within Hollywood, data from a variety of sources have revealed a strong correlation between the initial viral proliferation of #MeToo and wider narrative and cultural change. For instance, traffic to the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s page about sexual harassment saw a significant spike beginning in October 2017, when a total of 66,625 unique visitors came to the website, more than double the number of visitors from the previous month.[15]

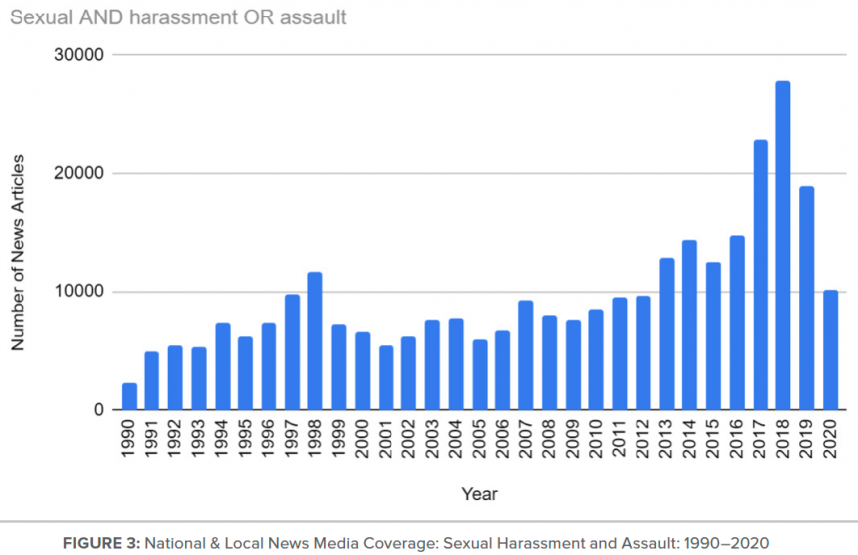

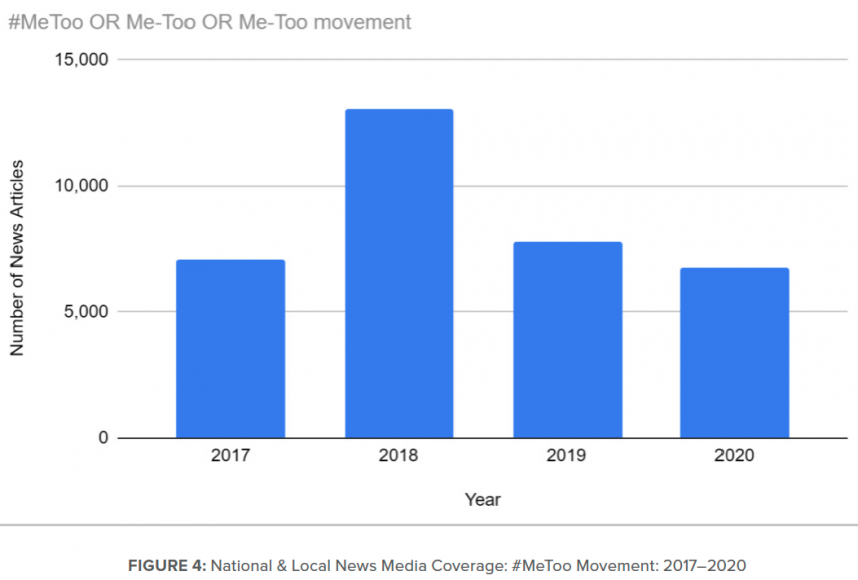

A similar pattern is observed in the national and local news media, with a clear correlation between increased discussion of #MeToo and a dramatic increase in news media coverage of sexual assault, harassment, and related topics. While overall coverage related to sexual violence had begun to increase in 2013, between 2016 and 2017, news media coverage of sexual violence saw a 65 percent increase as a direct result of #MeToo (see Figures 3 and 4).

Far from being restricted to the high-profile women, the culture of silence that had shrouded sexual violence in secrecy was ended as millions of women (and men) shared their long-buried experiences. This, in itself, was a momentous narrative shift. In Alyssa Milano’s words, the response gave people “a sense of the magnitude of the problem,” and the ground shifted.

#MeToo allowed survivors of sexual assault to reclaim their formerly “stigmatized narrative.” Past surveys have shown that up to 40 percent of women never disclosed to anyone, and of those who did, most confided only in a close friend. Scholars explain that:

Stigmatization depends on an implicit collective enforcement of the boundaries between public and private. Pregnancy loss, sexual assault, domestic violence, and other issues experienced by women have a long history of being excluded from the public sphere by being deemed private matters. Women who do choose to disclose publicly risk reactions of disbelief or worse, blame. Blaming survivors of sexual violence discourages further disclosures, effectively chilling the collective narrative of those who have been sexually harassed and assaulted. The totality and consequences of social stigma against disclosures of sexual violence paint a bleak picture of a culture where sexual violence against women is not recognized as the pervasive public health issue which it is.[16]

Through survivors’ access to social media, this previously hidden “collective narrative” was able to break through the “chill.” As one scholar put it, “Digital spaces create perpetual conversations, especially for marginalized folk who use social media as an access point they are often denied in live communication.”[17] Once those “perpetual conversations” reach a size and level of intensity that cannot be ignored by the mainstream media, they pose a counternarrative that has the capacity to capture the general public’s attention.

The term “hashtag activism” first appeared in news coverage in 2011 to describe the creation and proliferation of online activism stamped with a hashtag. It has been critiqued as “slacktivism” because it enables participants to feel that they have done something good when all they have done is make the minimal effort of clicking “like” to show support. Because of “slacktivism,” critics assert that social media movements rarely manifest in the physical world as actual protest movements. But in certain circumstances, social media in general, and Twitter in particular, can lead to a firestorm of political action and activity.

In their book #Hashtag Activism: Networks of Race and Gender Justice, communication scholars Sarah Jackson, Moya Bailey, and Brooke Foucault Welles argue for:

the importance of the digital labor of raced and gendered counter-publics. Ordinary African Americans, women, transgender people, and others aligned with racial justice and feminist causes have long been excluded from the elite media spaces yet have repurposed Twitter in particular to make identity-based cultural and political demands, and in doing so have forever changed national consciousness. From #BlackLivesMatter to #MeToo, hashtags have been the lingua franca of this phenomenon.

It is fair to say that #MeToo has been one of the most, if not the most, successful example of hashtag activism to date. The early participation of celebrities with their huge numbers of Twitter followers was a major factor, but so too was the fact that the pump had been primed by earlier online efforts to bring attention to the issue of sexual violence:

The #MeToo boon was made possible by its predecessors and by the digital labor, consciousness raising, and alternative storytelling done by #YesAllWomen, #SurvivorPrivilege, #WhyIStayed, #TheEmptyChair, and many other hashtags and conversations about gendered violence that were pushed into visibility by women and their allies on Twitter.”[18]

In the ensuing days, weeks, and months survivors’ stories continued to reverberate in both traditional and social media. Three days after the Milano tweet, gymnast McKayla Maroney tweeted about her sexual assault at the hands of Larry Nassar, USA Gymnastics national team doctor at Michigan State University. After that, more than 150 others came forward and shocked the nation with their stories of abuse by Nassar when they were young gymnasts. The issue was kept alive by a steady stream—some might say cascade—of accusations against men, many of them celebrities, politicians, or titans of industry, who then resigned, were fired, or were replaced. An incomplete list for the last quarter of 2017 includes:

OCTOBER

Chris Savino, creator of Nickelodeon’s The Loud House; Mark Halperin, political journalist; Cliff Hite, Ohio state senator; Kevin Spacey and Andy Dick, actors; Michael Oreskes, head of news at NPR; Roy Price, head of Amazon Studios.

NOVEMBER

Don Shooter, Arizona state representative; Dan Schoen, Minnesota state senator; Louis C.K., comedian and producer; Tony Mendoza, California state senator; Andrew Kreisberg, executive producer of superhero dramas; Steve Lebsock, Colorado state representative; Jeff Kruse, Oregon state senator; Senator Al Franken (D-MI); David Sweeney, chief news editor at NPR; Charlie Rose, television host; Matt Lauer, television news anchor.

DECEMBER

James Levine, conductor at the Metropolitan Opera; Peter Martins, ballet master in chief, New York City Ballet; Lorin Stein, editor of The Paris Review; Matt Manweller, Washington State representative; Leonard Lopate, host on New York Public Radio; Jerry Richardson, owner of the Carolina Panthers NFL team; Trent Franks, U.S. Representative for Arizona; John Moore, Mississippi state representative.

Time Magazine named “the Silence Breakers,” the men and women who spoke about their experiences with sexual misconduct, as Person of the Year in 2017. On January 1, 2018 the Time’s Up initiative was announced. Spearheaded by 300 women working in entertainment, its mission statement says:

By helping change culture, companies, and laws, TIME’S UP Now aims to create a society free of gender-based discrimination in the workplace and beyond. We want every person—across race, ethnicity, religion, sexuality, gender identity, and income level—to be safe on the job and have equal opportunity for economic success and security.

On January 7, actors and actresses participated in a red carpet “blackout” by wearing black gowns and Time’s Up pins at the Golden Globe awards and Tarana Burke was introduced to the world. On January 20, millions participated in the second annual Women’s March. On March 4, #MeToo and Time’s Up came to the Oscars and Annabella Sciorra, Ashley Judd, and Salma Hayek, three of Weinstein’s many accusers, spoke of the movements and the changes they hoped to see take place in Hollywood and beyond. On April 16, Jodi Cantor and Megan Twohey of the New York Times and Ronan Farrow of the New Yorker won the Pulitzer Prize for public service for their investigation of Harvey Weinstein and company.

The ferocity of the movement and the speed with which powerful (and not so powerful) men were being toppled from their positions led to a backlash from both the left and the right. In a piece entitled, “It’s Time to Resist the Excesses of #MeToo,” conservative commentator Andrew Sullivan dismissed it as a “moral panic” that would “at some point exhaust itself.” “Politically Incorrect” Bill Maher worried that “fragile” millennials were “going to bleed what is so great out of life” by being oversensitive. Contrarian feminist Katie Roiphe published “The Other Whisper Network” in Harper’s Magazine in which she accused “the feminist moment” of #MeToo of “great, unmanageable anger…that can lead to an alarming lack of proportion.” Many other articles of similar ilk were published in the early months of the movement, along with responses from equally passionate defenders. But these controversies did not alter the narrative shift’s inexorable advance, at least among women. According to a Vox-commissioned survey conducted in March 2018, 71 percent of women under the age of 35 and 68 percent of women age 35-plus said they supported #MeToo.

Feminist legal scholar Catharine MacKinnon, who was the architect of interpreting sexual harassment in the workplace as a form of sex discrimination prohibited by federal law, has described #MeToo as “a cataclysmic transformation” that is “shifting gender hierarchy’s tectonic plates.” Because of #MeToo:

Sexual abuse was finally being reported in the established media as pervasive and endemic rather than sensational and exceptional…. Sexual abuse is being unearthed in every corner of society—sports as well as entertainment, food as well as finance, tech and transportation as well as employment and education, children as well as adults. As staggering as the revelations have been to many who failed to face the long-known real numbers, the structural place of this dynamic has only begun to be exposed[19]

Because of #MeToo, the conversation began to change.

#METOO IN THE NOW: ONLINE DISCOURSE 2018–2020

While Harvey Weinstein and the entertainment industry played a central role in propelling #MeToo into a global movement, an analysis of more recent data highlights the longer-term impact of the initial hashtag, specifically the tensions that have emerged as discourse has become increasingly politicized across party lines.

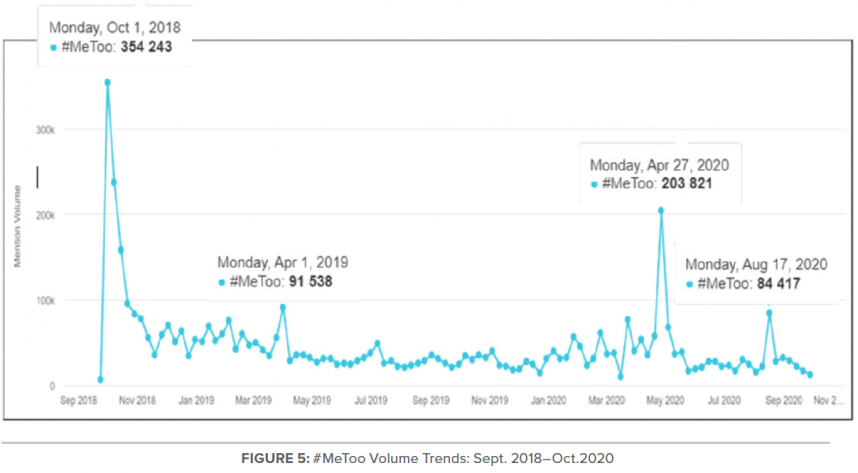

Between September 2018 and October 2020, a further 5 million unique social media posts were generated referring to “me too” or the “me too movement” in the United States, highlighting the continued momentum of the movement and hashtag. As seen in Figure 5, the significant spike in engagement driven by the Brett Kavanaugh confirmation hearing in October 2018 was a pivotal point in terms of the volume of online discourse, with commentary around the hearing generating 867,000 posts from nearly 300,000 unique authors.

Alongside generating a significant volume of social media content, online commentary around Brett Kavanaugh singled an important turning point in focus of online discourse related to #MeToo. Since the end of October 2018, #MeToo experienced three additional spikes in online engagement:

- April 1, 2019: Following widespread media coverage of Lucy Flores’s and Amy Lappos’s accusations of sexual harassment against Joe Biden

- April 27, 2020: Widespread media coverage of Tara Reade’s allegations of sexual harassment against Joe Biden

- August 17, 2020: Controversy following Bill Clinton’s presence at the Democratic National Convention

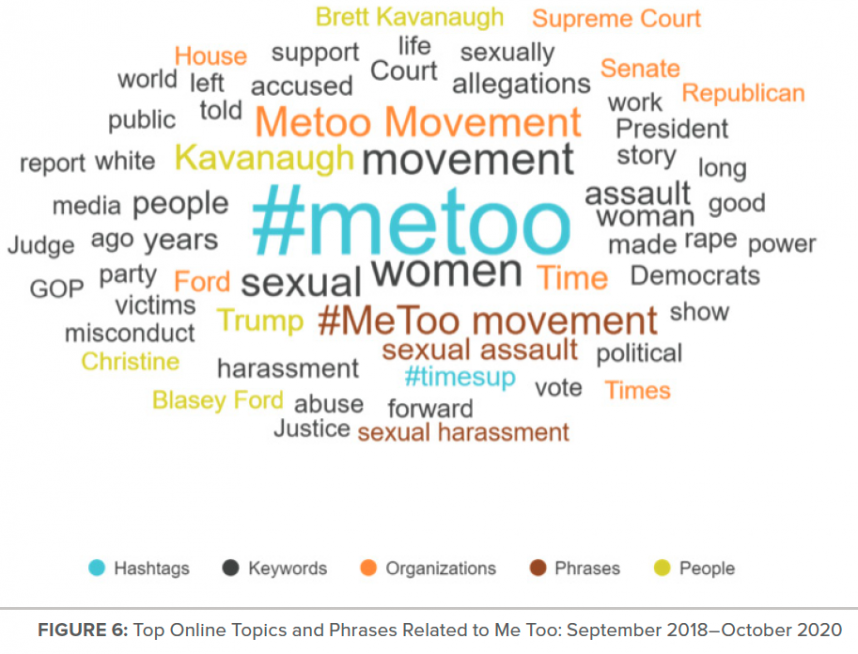

All three spikes in engagement were linked by a central theme—that is, the growing partisanship with which discussions of sexual violence and belief of survivors appears to be governed. The visualization of the top topics/phrases to dominate social media discourse between September 2018 and October 2020 (Figure 6) highlights how political figures accused of sexual assault and harassment have become a prominent feature of online discourse. In addition to Kavanaugh, “Trump,” “President, “Senate,” and “Biden” appear as some of the most prominent topics of focus in overall online discourse related to #MeToo within the same timeframe.

The more prominent focus on high-profile political figures is just one example of how #MeToo discourse online has become increasingly muddled by those seeking to discredit political opponents. It also points to the tension between the heightened calls to “believe survivors” and the continued concessions made for powerful men, particularly when the belief or disbelief in a survivor intersects with political affiliation. This tension is clearly seen in the discussions of accusations facing now President Joe Biden. While opinion of #MeToo has always been split across party lines (in a May 2018 poll by Morning Consulting, 81% of Democrats said they backed the movement, compared with 54 percent of Republicans),[20] the commentary surrounding Tara Reade has been largely shadowed by partisanship.

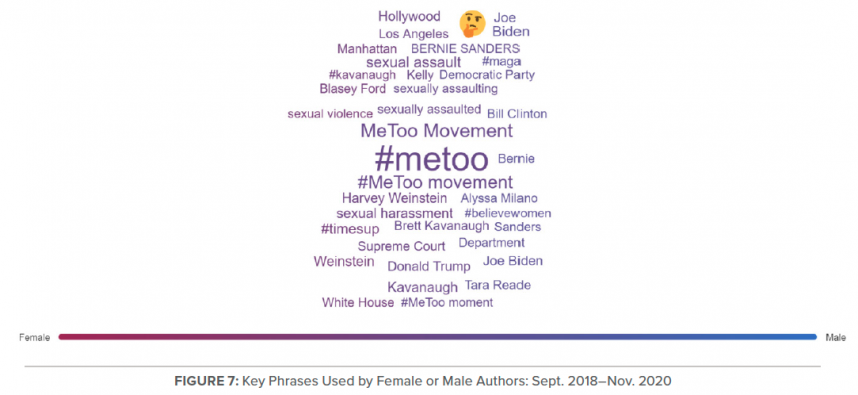

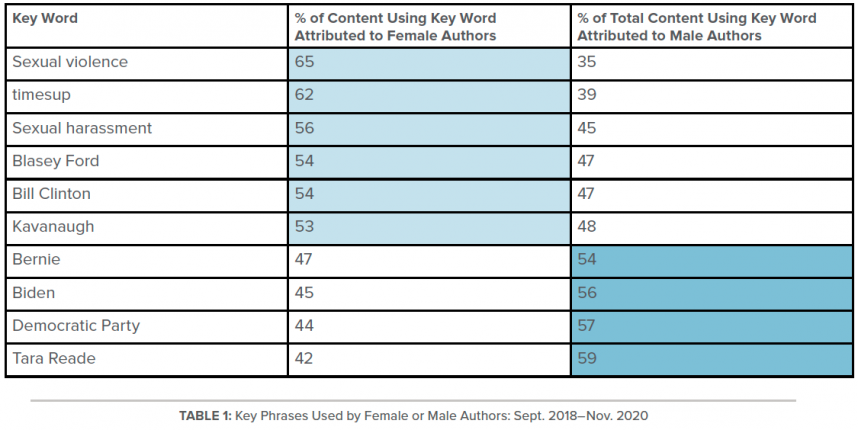

While these attempts to co-opt the movement for political purposes have become a prominent feature of online discourse since 2018, online data also indicate that a large portion of women continue to engage with #MeToo as an avenue to challenge the culture of sexual violence. Figure 7 visualizes the phrases commonly found within mentions according to association with male or female authors.[21] Between 2018 and 2020, identifiable female authors were significantly more likely than their male counterparts to mention “times up,” “sexual violence,” and “sexual harassment” in relation to #MeToo. At the same time, identifiable male authors were more likely to mention “Bernie,” “Biden,” and “Democratic Party” in relation to #MeToo than their female counterparts, reflecting the differing priorities, and more partisan motivations, of many male authors.

While the longer-term impact of this global movement is yet to be realized, because of #MeToo, the conversation began to change.

THE SURVIVORS’ AGENDA

On June 25, 2020, in the midst of both the coronavirus pandemic and the Black Lives Matter protests over the police murder of George Floyd, an online panel discussion was held to announce the launch of Survivors’ Agenda, whose mission statement reads:

In October 2017, the world shifted as millions of people raised their hand to say ‘me too.’ This shift has impacted the personal lives of millions, and entered the cultural zeitgeist in an unpredictable and unprecedented way. Two years later, we are still experiencing the ripple effects of the moment, and shifting into how a movement is born from its wake. The Survivors’ Agenda Initiative is about building power and changing the conversation—especially for those most marginalized and kept down by the structural oppressions of our society.[22]

With more than 700 participants in virtual attendance, six leaders representing organizations that represent women of color spoke.[23] Emphasizing the need for an intersectional approach that recognizes the various forms of “interlocking oppression” people of color and other marginalized people face, their remarks embrace the components of a bold new narrative about sexual violence in America from which four main pillars emerge.

THE FOUR PILLARS OF A NEW NARRATIVE

Listen to and believe survivors.

So many survivors have been speaking out and organizing, and we’re still struggling to have our voices heard. And the dominant narrative still blames us and shames us at worst, or, at best defines us as victims without power, without agency and without leadership capacity. And so that means that when these solutions get developed, if they get defined, it’s too often without us. And so the only thing that really shifts that dynamic is us organizing as survivors together, building our power together. And that’s what this is all about.

Survivors come from diverse backgrounds; the most marginalized voices must be included and amplified.

People of color, Black people and other marginalized groups feel unseen; not in the mainstream. We don’t see ourselves in the media or on the news unless it’s to benefit the media.…We are prioritizing the most marginalized. This work is being led by folks who represent those groups. And it’s in our principles to uplift and amplify those voices. It’s not just survivors that don’t get heard, but as you add the intersections of who we are as survivors: disabled, queer, veteran, I mean you can go down the list of people whose voices get pushed to the side.

Surviving sexual violence can lead to a lifetime of trauma; it is a public health crisis and survivors need and deserve respect and help.

Violence is not just between white men in uniforms and folks on street corners. Violence also looks like intimate partner violence, domestic violence, and sexual abuse. It also looks like the intimate ways that it lives in our home, in our communities. We understand that sexual abuse is a public health crisis. Too long it has been told that it is a personal issue. But we are here saying that it is a public health crisis…. What do we need to feel safe, loved and cared for by our communities and by lawmakers?

The culture must change; institutions must be held accountable; new systems must be created.

When we consider the kinds of systems that have to exist to eradicate sexual violence, it’s an xercise in thinking about what are the changes that have to be made within the systems, and also re-imagining what justice and safety look like…. What is a system that promotes healing? What are the systems that promote prevention? And what are the kinds of teachings that we’re offering to people so that we can create a new world that is free of violence? When it comes to the eradication of violence, we have to acknowledge the fact that there are power imbalances that have allowed people to perpetuate violence without any accountability…. So, when we think about gender inequality and the ways in which we have sexual violence happening in the workplace, it’s because people think they can wield power over survivors. That exists because of systems of discrimination and inequality.

CONCLUSION

The stories that we are trying to undo are longstanding and extraordinarily deeply embedded and it’s going to take a while to uproot them. I’m optimistic because we’re in the middle of tightening and weaving together a new story and it’s through activism and engagement that we will open people’s minds to something different. But it would be wrong to suggest that we are not still grappling with old tropes like survivors lie and this being an individual, not a societal, problem. We are grappling with these old tropes every day across the nation.”

Two significant events in the midst of #MeToo showed the continuing power of rape myths on the one hand and the public’s changing consciousness about the realities of sexual violence on the other. In September 2018 a woman named Christine Blasey Ford accused Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh of a sexual assault committed when they were teenagers. In a tumultuous televised Senate hearing, Blasey Ford was interrogated by a seasoned female sex crimes prosecutor hired by the all-male Republicans on the Senate Judiciary Committee “as an appropriate reflection of the seriousness” of the hearing. Democrats on the committee complained that having a prosecutor rather than a committee member doing the questioning gave the impression Blasey Ford was on trial, and indeed the questions posed were geared toward undermining her credibility.[24] Kavanaugh’s testimony was described by one reporter as “a combination of anger and pathos” during which he lashed out at Democrats and what he called a “grotesque and co-ordinated character assassination,” warning darkly, “what goes around comes around.”[25] The Senate’s very partisan vote to elevate this man to the highest court could be described as a classic case of rape myth acceptance.

In contrast, the jury’s conviction of Harvey Weinstein in February 2020 showed that people are ready, willing, and able to reject longstanding rape myths. Weinstein’s defense made much of the fact that some of the women who testified against him had maintained a relationship with him after the assault occurred, arguing that would never have happened if there had really been nonconsensual sex. But the prosecutors called veteran forensic psychiatrist Dr. Barbara Ziv, who had testified at Bill Cosby’s criminal trial the year before. Through her expert testimony she exposed and undermined a number of rape myths and explained to the jury that the failure to report a rape and the maintenance of contact with the perpetrator after the assault did not support Weinstein’s claims that the acts of which he was accused were consensual. She testified that it was very rare for a woman who has been sexually assaulted by someone she knew—which is the case in 85 percent of rapes—to tell others about it. It is rarer still for her to report the crime to the police. And she testified that victims typically do continue contact with their perpetrator, including texting, calling, and even having a relationship with their rapist. On February 24, the jury found Weinstein guilty, and a month later he was sentenced to 23 years in prison. Headlines emphasized the historical significance of the conviction:

- Harvey Weinstein sentenced to 23 years in prison in landmark #MeToo case, NBC News

- Harvey Weinstein’s sexual assault and rape convictions marked a major #MeToo moment, CNN

- Weinstein faces sentencing, prison in landmark #MeToo case, AP

Will this new movement against sexual violence succeed where its precursors have not? Much will depend on its efforts to bring about narrative shift, and in this regard, there is reason to be hopeful. Narrative shift is an explicit goal of #MeToo: “We are about strategizing action to disrupt rape culture, and shifting the narrative to bring these conversations into the powerful spaces where change happens.”[26] With its focus on how different forms of oppression intersect because of oppressive systems, this movement has the potential to bring about the fundamental change necessary to minimize the public health threat that is sexual violence in America.

1 Carly Gieseler, The Voices of #MeToo: From Grassroots Activism to a Viral Roar, (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2019, 170.

2 https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/sffucrp.pdf

4 https://www.motherjones.com/crime-justice/2019/10/campus-sexual-assault-survey/

5 World Population Review is a website dedicated to global population data and trends.

9 This criticism, of course, did not apply when Black men were accused of sexually assaulting white women.

11 Edwards KM, Turchik JT, Dardis T, Reynolds N, and Gidycz CA, Rape myths: History, individual and institutional-level presence, and implications for change. Sex Roles, 2011:65, 761–773.

13 Beck, et al., “Violence Against Women in Video Games: A Prequel or Sequel to Rape Myth Acceptance?” Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 2012.

14 Garland et al., “Blurring the Lines: Reinforcing Rape Myths in Comic Books” (Feminist Criminology, 2015).

15 Chiwaya, Nigel, “New data on #MeToo’s first year shows ‘undeniable’ impact,” NBC News, October 2018, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/new-data-metoo-s-first-year-showsundeniable-impact-n918821?cid=sm_npd_nn_tw_ma

16 Ryan Gallagher, Elizabeth Stowell, Andrea G. Parker, and Brooke Foucault Welles. “Reclaiming stigmatized narratives: The networked disclosure landscape of #MeToo.” Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction. November 2019:96. https://doi.org/10.1145/3359198

17 Carly Gieseler, The Voices of #MeToo: From Grassroots Activism to a Viral Roar (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2019.

18 Sarah J. Jackson, Moya Bailey, Brooke Foucault Welles, #Hashtag Activism: Networks of Race and Gender Justice (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2020).

19 Where #MeToo Came From, and Where It’s Going, The Atlantic, March 24, 2019.

20 https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/are-americans-more-divided-on-metoo-issues/

21 It is important to note significant limitations of these data. First, the data do not account for non-gender binary individuals. Also, gender identification is based on self-identification and is likely to be skewed by bots, dummy accounts, and misidentification.

22 Emphasis added.

23 They were Nikita Mitchell, Rising Majority; Ai-jen Poo, National Domestic Workers Alliance; Monica Ramirez, Justice for Migrant Women; Tarana Burke, ‘me too’; Michelle Grier, Girls for Gender Equity; and Fatima Goss Graves, National Women’s Law Center.

25 https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-45660297

26 me too. Impact Report 2019, p. 8