INTRODUCTION

Welcoming a baby into the world should be a time of joy and excitement. But for many Black mothers in the United States, childbirth is a milestone where racial stereotypes, systemic racism, and healthcare inequities collide, leading to disparate and harmful outcomes and experiences.

Welcoming a baby into the world should be a time of joy and excitement. But for many Black mothers in the United States, childbirth is a milestone where racial stereotypes, systemic racism, and healthcare inequities collide, leading to disparate and harmful outcomes and experiences.

The United States is the only industrialized nation in the world where maternal mortality is rising. Black women are three to five times more likely to die from pregnancy complications than white women[1], and 80 percent of those deaths are preventable.[2] Similarly, relative to other infants, Black infants are more than twice as likely to die before their first birthday.[3] If the health of a society can be measured by its maternal and infant mortality rates, the United States is failing.

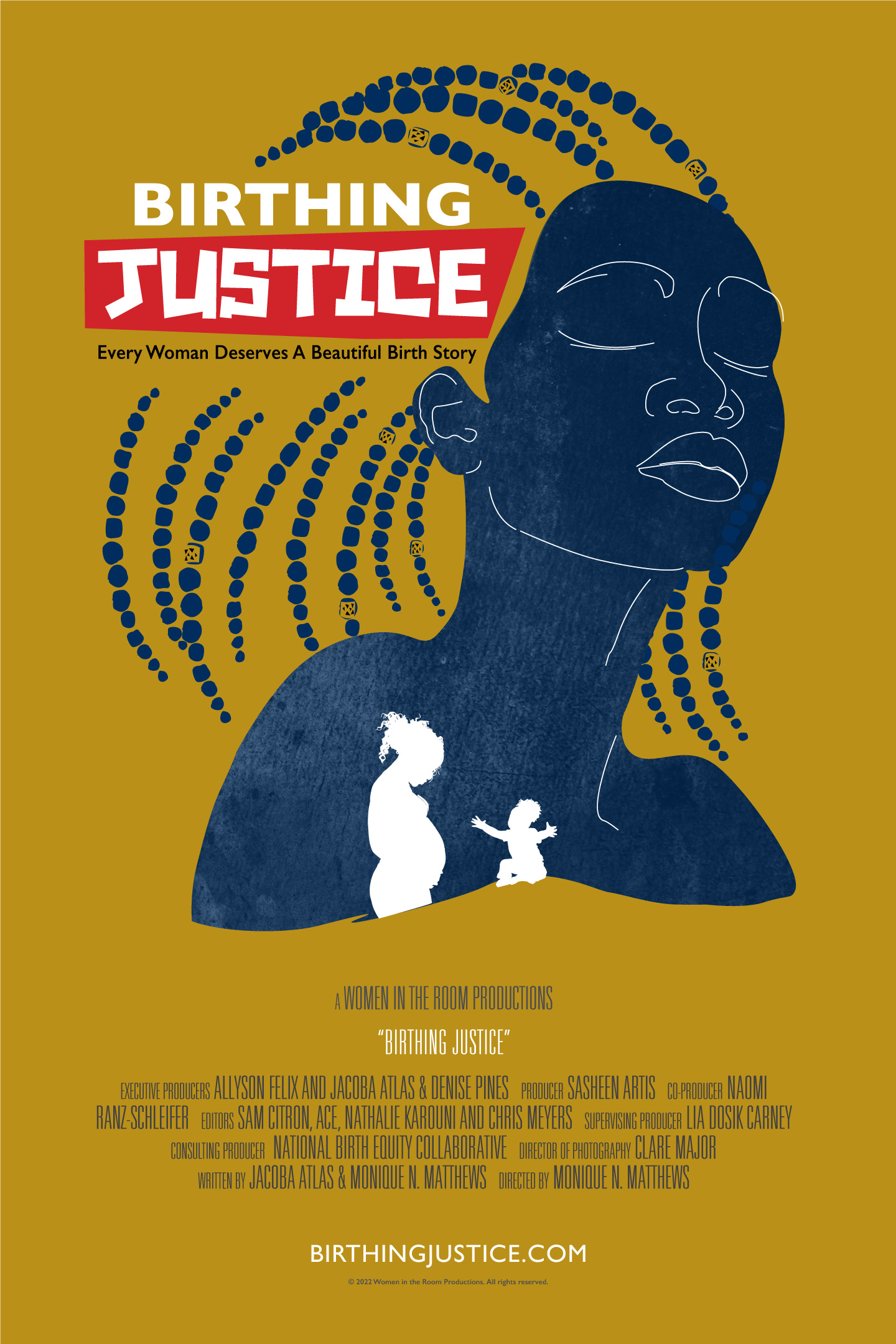

Women in the Room Productions’ documentary, Birthing Justice, addresses this national crisis by turning the spotlight on the progress being made by health initiatives and uplifting evidence-based practices to adopt more widely. With input from advocates and leaders in the birthing justice movement, the film offers solutions that can be implemented in communities across the country. From supporting Black doulas and midwives to embracing practices that ensure Black mothers are heard and listened to, the film directs viewers to solutions for reproductive justice.

SOCIAL ISSUE BACKGROUND

The color of one’s skin should not determine the quality of healthcare a woman receives during pregnancy. Yet the following statistics show how interpersonal racism and implicit bias – along with structural racism – have tragically led to substandard healthcare for Black mothers in the United States:

- Black women are three to five times more likely to die from pregnancy complications than white women.

- Preeclampsia/eclampsia is the leading cause of maternal death among Black women.[4]

- Black mothers experience stillbirths at double the rate of white mothers.[5]

- Black infants die at two to three times the rate of white infants.

These discrepancies persist regardless of a mother’s socioeconomic status or education. Changes to the system can help dramatically. For example, when Black babies are delivered by Black doctors, their mortality rate is cut in half.[6] Developing pathways to diversify clinical care teams, specifically training and investing in Black providers in the healthcare system, are what Birthing Justice and The Opportunity Agenda are advocating for.

When watching Birthing Justice, we encourage you to consider the courage and resilience of the interviewees sharing their stories. The documentary follows Black women through pregnancy, delivery, and the postpartum period—exposing the challenges Black mothers encounter, including genetic predispositions, chronic stress, racial bias, disrespectful care, and barriers to adequate healthcare.

Historically, the narrative around the Black/white disparity in infant mortality placed the blame on Black mothers. In fact, investigations conducted more than two decades ago revealed the racist diagnosis accepted by medical professionals that poor, less-educated women of color put their lives and the lives of their children at risk by smoking, drinking, using drugs, and not eating right.[7] It was also unbelievably speculated that Black mothers should be held responsible for their pregnancy losses (including miscarriages and stillbirths) if they were too young, unmarried, or didn’t seek medical help during and after their pregnancies.

Birthing Justice disproves these harmful narratives, revealing how inequitable systems and structures have resulted in racial injustices in maternal and infant health. The film shows how we can come together to end this national tragedy by supporting policy solutions that provide Black mothers with resources that allow them to make informed decisions for themselves and their families.

We encourage you to consider the courage and resilience of the interviewees sharing their stories.

DISCUSSION BACKGROUND

Admittedly, it can be very uncomfortable to have discussions about mortality, racism, and reproductive health. Many of us may feel defensive or not heard when we have these conversations. We understand that.

We also know that open and respectful dialogue allows us to grow as individuals and as a community. Most people have long held and often distorted views about race, racism, mothers, and Black women, so it is important to be open to hearing different perspectives and experiences.

As community members, we share many of the same values: family, health, fairness, and justice. A willingness to have these uncomfortable conversations ensures that everyone experiences the ideals behind these values. We encourage you to enter the discussion about Birthing Justice with an open mind and an eagerness to share your experiences with others who may benefit from watching the film.

We want to acknowledge that the film presents sensitive subject matter, particularly for those who have experienced birth trauma and their families.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- How did the film challenge your previously held perceptions about Black mothers, reproductive health, or the medical industry?

- What kinds of stereotypes or media representations have you seen about Black mothers before watching Birthing Justice?

- How do you think those stereotypes and/or media representations have impacted the outcomes discussed in the film?

- Were you surprised to learn that all Black mothers, including well-educated and financially secure ones, and even famous women, can experience racism in maternal health?

- Why do you think there is unequal access to medical services? How might the history of the medical profession and systemic racism explain these inequities?

- How do you think we can eliminate bias in our healthcare system?

- What are ways that health care institutions can be held accountable in providing Black women and birthing people with respectful maternity care?

- What do you think the impact of anti-abortion laws will be on people who are living in poverty? How do you think we should prepare medical professionals for these situations?

- How might you support Black women and birthing people in accessing resources about midwives, doulas, and other providers who embrace holistic healthcare practices?

PERSONAL REFLECTION

- I relate most with [someone from film] . . .

- This documentary made me feel . . .

- Healthcare in this country should be . . .

- Black women and birthing people deserve . . .

It is important to also discuss legislative solutions for our nation’s Black maternal health crisis. For example, members of Congress have been considering a 12-month postpartum Medicaid coverage package that would offer significant support to low-income Black mothers. This, along with the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act, would provide essential coverage for Black birthing people.

When it comes to finding systemic solutions, we believe that government plays a role. In addition to federal policies, there may also be local legislation on the books in your state to address the crisis. We encourage you to reach out to the following advocacy groups to get involved:

GET INVOLVED

Many organizations are working to improve Black maternal health outcomes. You can support and invest in these national and local groups through donations, by following them on social media, or by sharing information about them with others in your network.

Birth Injury Center

Birth injuries can transform the celebratory moment of a child’s birth into a lifelong nightmare that includes serious health complications, permanent disability, or death. The Birth Injury Center provides support and resources to families impacted by birth trauma.

Black Mamas Matter Alliance (BMMA)

A national network of Black women-led and Black-led birth and reproductive justice organizations and multidisciplinary professionals who work across the full spectrum of maternal and reproductive health.

Black Maternal Heath Caucus

Launched by Congresswomen Alma Adams and Lauren Underwood, this caucus is dedicated to elevating the Black maternal health crisis within Congress and advancing policy solutions to improve Black maternal health outcomes and end disparities.

Black Women Birthing Justice

A grassroots collective of Black women and individuals across the African diaspora committed to transforming birthing experiences for Black women and birthing people.

Black Women for Wellness

An organization committed to the health and well-being of Black women and girls through health education, empowerment, and advocacy.

Center for Black Women’s Wellness

A premier, community-based, family service center committed to improving the health and well-being of underserved Black women and their families.

Community of Hope’s Family Health and Birth Center

This facility includes a nationally accredited Birth Center and provides a range of healthcare services for entire families, with a special focus on serving pregnant parents and their babies.

Every Mother Counts (EMC)

EMC works to make pregnancy and childbirth safe for every mother, everywhere, by raising awareness, investing in solutions, and mobilizing action.

Moms Rising

A network of people taking on the most critical issues facing women, mothers, and families, as well as educating the public and mobilizing grassroots action to build a more family-friendly America.

National Association to Advance Black Birth (NAABB)

An organization that advocates for Black maternal-infant health through advocacy, research, educational programming, activism, and policy change.

National Black Equity Collaborative (NBEC)

NBEC works for birth equity for all Black birthing people, with a willingness to address racial and social inequities in a sustained effort.

SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective

This organization is dedicated to building an effective network of individuals and organizations to improve institutional policies and systems that impact the reproductive health of Black women.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

To learn more about Black maternal health:

Battling Over Birth: Black Women and the Maternal Health Care Crisis in California

By Chinyere Oparah, Linda Jones, Dantia Hudson, Talita Oseguera, and Helen Arega

This book documents the Black maternal health crisis and aims to ensure that every Black mother has an empowered birthing experience.

Implicit Bias Test

Founded in 1998, Project Implicit educates the public about their personal hidden biases and brings them to light through an online “virtual laboratory.”

Birthing Justice: Black Women, Pregnancy, and Childbirth

Edited by Julia Chinyere Oparah and Alicia D. Bonaparte

This book places Black women’s voices at the center of the debate on what should be done to fix the broken maternity system. It also foregrounds Black women’s agency in the emerging birth justice movement. Mixing scholarly, activist, and personal perspectives, the book shows readers how they, too, can change lives — one birth at a time.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special thanks to Denise Pines, I. India Thusi, Rahel Samantrai, Abby Akrong, Elizabeth Johnsen, Julie Fisher-Rowe, Cecilia Martinez, J. Rachel Reyes, Ellen Buchman, Isabel Morgan, and Lorissa Shepstone.

Women in the Room Productions is a comprehensive media company that drives social impact for women and persons of color through storytelling and community.

The Opportunity Agenda builds the public imagination and cultural will to challenge white supremacy. We advance narratives that support opportunity for all and work in community with partners to overcome opposition narratives that exclude and divide us. www.opportunityagenda.org

CITATIONS

1 Marian F. MacDorman Marie Thoma, Eugene Declcerq, & Elizabeth A. Howell, Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Maternal Mortality in the United States Using Enhanced Vital Records, 2016-17, 111 Am. J. Pub. Health 1673 (2021).

2 Trost, Susanna, MPH, et al. Pregnancy-Related Deaths: Data from Maternal Mortality Review Committees in 36 US States, 2017–2019 | CDC

3 Ely DM, Driscoll AK. Infant mortality in the United States, 2020: Data from the period linked birth/infant death file. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 71 no 5. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2022. DOI: https://dx.doi. org/10.15620/cdc:120700.

4 Black Women Over Three Times More Likely to Die in Pregnancy, Postpartum Than White Women, New Research Finds, PRB (Dec. 6, 2021), https://www.prb.org/resources/black-women-over-three-times-more-likely-to-die-in-pregnancy-postpartum-than-white-women-new-research-finds

5 Black Mothers are More Likely to Experience Stillbirth, CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/stillbirth/features/kf-black-mothers-stillbirth.html#:~:text=Stillbirth%20rates%20were%20higher%20in,to%20Hispanic%20and%20white%20mothers (last updated Nov. 3, 2022).

6 Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, Sojourner A. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020 Sep 1;117(35):21194-21200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1913405117. Epub 2020 Aug 17. PMID: 32817561

7 PH Wise & DM Pursley, Infant Mortality as a Social Mirror.