From the perspective of most scholars who focus on the topic, there is a clear causal story that links media representations of black men and boys to real-world outcomes. The story can be summarized as follows:

- For various reasons, media of all types collectively offer a distorted representation of the lives and reality of black males.

- In turn, media consumption negatively affects the public’s understandings and attitudes related to black males (sometimes including the understandings and attitudes of black males themselves)

- Finally, these distorted understandings and attitudes towards black males lead to negative real-world consequences for them.

Taken as a whole, this is a rich area of study, which many scholars believe is central to understanding and addressing the stubborn challenges faced by black boys and men in American society. (Note that many studies refer to race without explicitly addressing gender, but many patterns, such as exaggerated associations with violence or sports, are clearly more relevant to males than to females.)

For advocates and other communicators concerned with issues related to black male achievement, it is important to be sharply aware of this story, and the findings that support it, so that they can address the problem in an informed way.

Note that other important components of the black male dilemma do not fall within the scope of this paper. Historical legacies of slavery and Jim Crow, the material and economic disparities related to that and other forms of historical racism, the role of the criminal justice system in controlling black males, the flow of resources toward and away from black males, and so on, are all important issues for understanding the current situation for black males in America. They will not be addressed here, however, except insofar as the distorted images in media make it easier for many Americans to tolerate, perpetuate, ignore or discount the many real disadvantages that black males face.

This paper breaks the story down into five “links in the chain” (some of which have been studied and discussed more than others):

- Distorted portrayal of black (male) lives/experience

- Why media patterns are distorted

- Causal link between media and public attitudes

- Documentations of the public’s bias — both conscious and unconscious — against black males

- Practical consequences for the lives of black males

Distorted Patterns of Portrayal

In a wide range of ways, the overall presentation of black males in the media is distorted, exaggerating some dimensions while omitting others. Many scholars have contributed to a robust body of research documenting these distortions, which have several aspects.

Underrepresentation in media portrayals

A number of researchers have essentially conducted “censuses” (of representations overall, of fictional characters, of characters in ads, and so forth) and compared these findings to the numbers of black men and boys that would be expected if racial bias were not at work. As this research has progressed, analysts have grown more sophisticated in the distinctions that they draw about where black males do and do not appear in the media. A pattern reported again and again is that African Americans are underrepresented in various facets of the media’s portrayal of the world.

For example, although characters of color in video games have been increasing over time, blacks in general tend to be underrepresented especially as active, playable characters in video games. They are more likely to be stock characters in the story.

…outside of sports games, the representation of African Americans [in popular video games] drops precipitously, with many of the remaining featured as gangsters and street people … (Williams et al., 2009)

Black males also tend to be underrepresented as experts called in to offer commentary and analysis in the news. News programs frequently include “talking heads” invited to help clarify a given topic, but these tend not to be black males. In a 1997 sample of network news clips, black speakers accounted for less than 3 percent of the statements made by experts commenting on various issues. (Entman & Rojecki, 2000, p. 69)

Black males are underrepresented in the roles of computer users or technical experts in television commercials, instead tending to appear in roles that put less emphasis on intellectuality (see below). (Kinnick & White, 2001) African Americans are also underrepresented as users of luxury items in commercials, instead being featured using more pedestrian consumer products. (Henderson & Baldasty, 2003)

In short, the studies paint a picture of an American media landscape that includes fewer black males overall, few associated with technical and other intellectual pursuits, and few who fit Tucker’s description of “competent, capable, and successful members of businesses and families who have attained some degree of material wealth.” (Tucker, 2007, p. 69)

More subtly, as Entman and Rojecki (2000) point out, even in the cases when blacks appear in the media as sympathetic and competent figures, they tend not to be “relatable” figures with whom the audience is asked to truly identify. They may not have names (black crime victims are often unnamed, as opposed to their white counterparts who are named); they may lack visible family lives (there are many fewer competent and successful black male fiction characters, compared with white characters); and so forth.

In the world as portrayed by the media, life is lived primarily by white (or other non-black) people, with black males, more or less sympathetic, in the background. (See also Bogle, 2003.)

Negative associations exaggerated

While many aspects of black males’ real lived experience tend to be missing from the collective media portrayal, some aspects are very much present, and are, in fact, exaggerated.

Perhaps the most-discussed pattern is the association between black males and criminality, particularly in television news — where they are not only likely to appear as criminals, but likely to be shown in ways that make them seem particularly threatening (compared with white criminals, for instance).

Blacks are overrepresented as perpetrators of violent crime when news coverage is compared with arrest rates [but are underrepresented in the more sympathetic roles of victim, law enforcer]. (Entman & Gross, 2008, p. 98, citing Travis L. Dixon & Daniel Linz, 2000)

…[in a small sample of local Chicago TV news from 1993-1994] stories about Blacks were four times more likely to include mug shots [than stories about Whites accused of crimes]. (Entman & Rojecki, 2000, p. 82)

African Americans are disproportionately represented in news stories about poverty, and these stories tend to paint a picture that is particularly likely to reinforce stereotypes and make it hard to identify with black males. For example, low-income blacks in news stories are more likely to live in slums or urban areas, as opposed to rural areas, than real-world averages would suggest; more likely be entirely unemployed and “idle” (as opposed to working); and so forth. The idle black male on the street corner is not the “true face” of poverty in America, but he is the dominant one in media portrayal. (Clawson & Trice, 2000, updated and confirmed in Clawson et al., 2007)

In the entertainment media as well, these and other associations continue to be systematically perpetuated. Analysts have gone into great detail about the way in which negative images of black males continue to be used for entertainment purposes, whether through traditional imagery of black inferiority (Bogle, 2003) or by using black male characters disproportionately to represent both the victims and perpetrators of violence. For example, one study examined music video violence statistically, for its impacts on adolescents:

Compared with United States demographics, blacks were overrepresented as aggressors and victims, whereas whites were underrepresented. White females were most frequently victims. Music videos may be reinforcing false stereotypes of aggressive black males and victimized white females. These observations raise concern for the effect of music videos on adolescents’ normative expectations about conflict resolution, race, and male-female relationships. (Rich et al., 1998)

Positive associations limited

As discussed, even when black males are presented sympathetically, they tend to be absent from some important types of roles, e.g., as fathers in parenting situations that audiences can relate to. On the other hand, black males are highly visible in other types of roles that can be considered positive. In the world as depicted by the media, blacks frequently excel in sports, and more generally, are associated with physicality and physical achievement — as well as the aggressiveness that usually goes along with this type of success.

In films, their characters tend to have “macho” qualities that are valued by Americans; however, these film representations can also exclude or obscure other everyday virtues.

… men of color are faced with achieving masculinity [in media representations] through their corporal selves as physical threats (i.e., as athlete or gang member) as opposed to their intellectual contributions. … To be viewed as assertive and aggressive is valued in the culture but comes at the expense of other highly valued qualities … (Messineo, 2008, p. 755)

Black men [in mainstream print ads], with rare exceptions, are represented as workers, athletes, laborers, entertainers, criminals, or some combination thereof. (Tucker, 2007, p. 70)2

In short, the media world is populated by some black males we admire, but these tend to be associated with a relatively limited range of qualities, such as physical ability and/or entertainment skills.

The “problem” frame

A consumer of most of American media can hardly help thinking of black males in terms of problems. This is not only because of distortions in the collective media presentation of black males (discussed previously), but also due to patterns that characterize sympathetic and accurate portrayals. For valid and important reasons, mass media, advocacy, and policy-making discourses tend to focus on (real) problems of black males — relating to educational and economic outcomes, family life, or the criminal justice system, for instance.

What are the implications when Americans as a whole strongly associate black males with intractable problems? The challenge, discussed in greater detail in later sections, is that frequent repetition of the problems of black males can obscure other, more positive dimensions of their reality, and worse, can end up reinforcing prejudicial stereotypes. The literature suggests — and the authors’ own research experience on a wide range of issues confirms — that an emphasis on negative outcomes often ends up triggering default (false) assumptions about how those problems arose, particularly due to faulty personal choices.

Even if the proportion of Black victims and criminals were to reflect defensibly “accurate” readings of actual crime patterns, in the absence of contextual explanations, the heavy prominence of a racial minority in these stories of violence may worsen negative stereotyping. (Entman & Rojecki, 2000, p. 81)

Negative stereotyping of minorities is often (if inadvertently) reinforced in newspaper reporting that addresses race-based health disparities. For example, [an article on high HIV rates among black males] reinforces negative stereotypes of Black men as threats not only to their own women and children, but to society at large . . . Because the article does not offer any underlying, structural reasons for the disparities mentioned . . . it ends up reinforcing negative racial stereotypes about Black criminality, drug use, destructive sexuality, and inadequate fatherhood. (Aubrun et al., 2007)

Advocates need to carefully consider the costs of such narratives, if they predominate to the exclusion of more positive narratives and images. (See discussion of “Dilemmas and Deep Challenges.”)

Missing stories

The media are principally in the business of storytelling, whether through journalism, fictional narrative and entertainment, reality TV, and even advertising, video games and music videos. Some analysts have tried to look not only at the kinds of characters that black males do or do not play, but also the kinds of stories that are told about them, or not told about them. Although we do not find much in the way of systematic or statistical censuses in the sociological literature, there are a couple of observations that seem clear.

Just as important as the patterns of distortion and exaggeration discussed so far is the fact that many important dimensions of black males’ stories are largely untold in the media — in particular how the lives of black men and boys are affected by larger contexts, such as historical antecedents of black economic disadvantage, persistence of anti-black male bias, and relative disconnection from the social networks that help create wealth and opportunity.

The media contribute to the denial component of racial sentiments mostly by what they usually omit. Examples include: the pervasiveness of present-day discrimination and, given the importance of capital accumulation, the enormous financial harm still imposed today by discrimination against past generations; the role that poverty and joblessness play in raising crime rates and lowering marriage rates among YMC [young men of color]; and the part played by larger structural changes in the global economy. (Entman, 2006, p. 13)

In short, according to the world as it is presented by the media, the suffering black males can easily be presumed to be solely responsible for their own fates. Without knowing these larger stories, the average person is left to assume that black males are innately or culturally inclined towards low achievement, criminality, and broken families.

In the authors’ own analysis of the stories that mass media tell about race,3 we found that:

The descriptions in the coverage tend to create and reinforce concrete images of people and families who are doing poorly and people who are “behaving badly.” While the focus on tangible, day-to-day problems such as sickness and poverty may help give readers a more vivid picture of disparities, this vividness actually works against bigger-picture understanding which would include more about causes, contexts, and solutions. (Aubrun et al., 2005)

Of course, stories addressing big-picture causality are not entirely absent from the media. For instance, they are a regular topic in the social network site BlackPlanet.com.4 They also appear sometimes in mainstream media discussions; enough, in fact, to be decried by racial conservatives such as African-American radio host Larry Elder:

The mostly well-intentioned but condescending members of the mainsrream media go the extra mile to avoid having charges of “racist” directed at themselves, so they seldom challenge “black leaders” when these race-baiters confuse equal rights with equal results. Thus, lower black college enrollment becomes “underrepresentation” in higher education; the fact that white net worth exceeds black net worth becomes “disproportionate”; data showing banks decline black loans more readily than loans to whites becomes “discrimination”; blah, blah, blah. (Elder, 2008, p. xv)

But the social science literature makes the overall pattern clear: Consumers of mainstream media receive overwhelmingly more “information” about individual African-American males than about the broader forces that shape their experience.

If advocates are working to help foster a different media environment, and the benefits that would follow, they cannot ignore these missing dimensions of the black male story — even if telling the stories is difficult and often triggers resistance.

Causal Link Between Media and Public Attitudes

Why study media portrayals? Of course, the reason that so much attention is devoted to media representations (in the broadest sense) is that the collective image of blacks and black males has important effects. Researchers state — sometimes with rigorous evidence, other times through common sense inference — that representations in the media affect viewers’ perceptions and, specifically, that distorted portrayals lead to distorted and/or negative perceptions. (Note that some of the evidence comes from studies of other ethnic groups.)

For instance:

- Patterns in portrayals of black men and boys can be expected to promote antagonism towards them.

- [We] can predict what watching local news might do to us. If subliminal flashes of black male faces can raise our frustration, as shown by the Computer Crash study [in which subjects responded with greater hostility to a crashed computer after being shown subliminal images of black faces], would it be surprising that consciously received messages couched in violent visual context have impact, too? (Kang, 2005, p. 1551)

- … White Americans tend to develop negative stereotypes towards Hispanic Americans when they depend on television to learn about them. This finding indicates that people are influenced by television images. The more negative images are shown on television, the more likely the viewers pick up the images and develop their stereotypes. (Dong & Murrillo, 2007)

- Patterns in portrayals of black males can be expected to promote exaggerated views of, expectations of, and tolerance for race-based socioeconomic disparities.

- [M]edia content — not just news but entertainment and “infotainment” — usually promotes White privilege and the idea that Whites occupy the top of a racial hierarchy wherein Blacks are largely and naturally relegated to the bottom. (Entman & Gross, 2008, p. 97)

- Patterns in portrayals of black males can be expected to promote exaggerated views related to criminality and violence.

- Patterns in portrayals of black males can be expected to work against identification with them.

- See Entman and Rojecki’s discussion of how television ads are much less likely to place African Americans in positions the audience relates strongly to (for instance, in close-ups, addressing the audience directly, first or last to appear on screen). (Entman & Rojecki, 2000, p. 168)

- Patterns in portrayals of black males can be expected to reduce attention to structural and other big-picture factors.

- Films that ameliorate White anxieties about Black men by turning them into comics or criminals to be laughed at and/or condemned further the state of racial denial that plagues the United States. … They ease White America’s discomfort and make it easy to sidestep its responsibility to acknowledge and to address persistent racial inequalities and conflicts. (Tucker, 2007, p. 102, drawing on Guerrero, 1993)

- Patterns in portrayals of black males can be expected to promote public support for punitive approaches to problems.

- For instance, presumably due to cumulative effects of viewing TV news that associates black males with crime, “heavy news viewers” in one study were more likely to support the death penalty after viewing crime news stories that did not even identify the race of the suspects. (Dixon & Azocar, 2007, p. 229)

An important research question has been whether media representations only reflect popular understandings that are already out there — or if they help create those understandings through repetition and exposure. A few studies help to directly establish this causal link.

It has been confirmed experimentally that exposure to stereotypical African-American characters and behaviors in entertainment programs has negative impacts on beliefs and attitudes about African Americans, as well as towards affirmative action policies. (Ramasubramanian, 2011)

If media consumption creates distorted understandings and attitudes, then more consumption should lead to more distortion. This is exactly the pattern observed in some studies, particularly when amount of consumption is balanced against amount of real-world experience with black males (or other ethnicities). Media images have the most impact on perceptions when viewers have less real-world experience with the topic.

[P]ersonal contact is critical to the development of a better understanding of other ethnicities. The more individuals interacted with other people who have different cultural backgrounds, the more likely these individuals could see the positive traits and characteristics of the other people. This finding suggests that human interaction and direct contact are keys to understanding between people and, in particular, among those who have different cultural backgrounds. (Dong & Murrillo, 2007)

[T]he more television White viewers consumed, the more their evaluations of Latinos reflected their [negative] TV characterization — markedly so when viewers’ real-world contact with Latinos was not close, resulting in a greater reliance on televised images in decision making. (Mastro et al., 2007, p. 362)5

Impacts on thinking of black males themselves

While black males obviously draw on far more experience than others to form images of themselves and their peers, they are not immune to the influence of the media portrayals, which they consume like other Americans. One of the most important general findings relevant to black males’ own thinking is that so-called “stereotype threat” is an important cause of black males’ relatively lower performance in certain contexts, such as standardized testing.

Research into stereotype threat usually involves giving people measurable tasks, while at the same time subtly reminding them of the stereotypes that might apply to them. A growing body of research led by Joshua Aronson, Claude Steele, and others shows that when a member of a group that suffers from stereotyping comes into a situation where that stereotype is highly relevant, they experience a number of effects that reduce performance. Increased anxiety, self-consciousness about performance, and efforts to suppress negative thoughts and emotions all use up mental resources needed to perform well on cognitive and social tasks. (Schmader et al., 2008) The more intense the stereotype threat, the more pronounced the impacts on the individual. (Aronson & Steele, 2005) For example, an elderly person, when reminded of how people often associate age with memory loss, will struggle more with memory tests. (Rahhal et al., 2001) Asian-American schoolgirls did worse than usual on math tests in situations that emphasized their gender (the stereotypical idea is that girls are supposed to be worse at math), and better than usual in situations that emphasized their Asian heritage (Asian Americans are “supposed to be” better at math). (Ambady et al., 2004)

Of course, black males are aware of stereotypes that peg them as unintelligent or under-achieving, and they consistently suffer from the self-handicapping that results from stereotype threat in contexts such as testing or job interviewing.

Interestingly, whites are also subject to a kind of stereotype threat. An experiment showed that when stereotypes about white racism were triggered, white males tended to place more physical and social distance between themselves and blacks, thereby acting in a manner that served to confirm the stereotype. (Goff et al., 2008)

Besides stereotype threat, researchers have also pointed to other damaging effects of media on the thinking of African Americans generally, and black males in particular. For instance, it has been shown that stereotypic images of black women increase their domestic victimization by their black male partners (Gillum, 2002), presumably by shaping males’ views of black female characters.

Another study focused on African Americans and “social capital.” There are a great many definitions of social capital in the literature, but most will agree that the term refers to people’s connections to each other in social networks (both virtual and actual), which provide financial, social, and other opportunities and important benefits. Telephone survey interviews conducted in St. Louis and Kansas City showed that African Americans are particularly vulnerable to diminishment of social capital as a result of media consumption (see Beaudoin & Thorson, 2006). Since blacks tend to watch more television overall, and tend to be especially attuned to representations of blacks (who are often framed negatively), their attitudes towards the people and community around them is negatively impacted, relative to white viewers. The survey showed that those who watched more television had less trust in and interaction with neighbors, lower likelihood of joining groups, and worse perceptions of the town they lived in. Together, these attitudes amount to a loss of social capital, making it less likely that blacks in these communities will be connected to others in ways that lead to improving life chances.

More generally, scholars find that images in the media have a negative impact on black people’s perceptions of self and of their communities, though there is no shared consensus on how exactly this plays out. Various mechanisms may be at play:

- Negative stereotypes (thugs, criminals, fools, and other disadvantaged types) are demoralizing and reduce self-esteem and expectations.

- The most common “role models” depicted in media (e.g., rap stars or NBA players) present limited, often unrealistic, options.

- More positive or realistic role models tend to be lacking.

When certain types of negative or limiting images are produced by “black sources,” the impact can be particularly strong.

When these images of sex object and aggressive male are presented as part of the dominant ideology, men and women of color can reject the imagery as imposed from outside. However, when this imagery is presented as from the ingroup, the risks of self-objectification are heightened. (Messineo, 2008, p. 755)

Researchers also have confirmed that the media creates rather than reflects negative understanding, finding, for example, that the higher the consumption of media, the lower the self-esteem among African Americans. (Tan & Tan, 1979)

Psychological and developmental studies have also begun to look at particular times of life (such as childhood and adolescence) when black boys are most susceptible to media influences, and the psychological strengths or stresses that seem to affect how deeply these influences impact them. (Martin, 2008; Banks & Grambs, 1972)

Documentations of Bias — Conscious and Unconscious — Against Black Males

Another robust and profoundly important area of study focuses on mapping current attitudes towards blacks and black males, whether conscious or unconscious. Most importantly, a rich set of studies, including cleverly designed psychology experiments (especially Implicit Association Tests), makes it clear that many if not most non-blacks have negative unconscious associations with black males, even if they have no consciously biased attitudes. And many African Americans share these negative associations toward their own group.

As Kang observes in an extensive review of “the remarkable findings of social cognition,” among other topics:

Not only do they provide a more precise, particularized, and empirically grounded picture of how race functions in our minds, and thus in our societies, they also rattle us out of a complacency enjoyed after the demise of de jure discrimination. (Kang, 2005, p. 1495)

In this section we review several examples of the findings from this type of literature as well as more traditional investigations of attitude. While the topic of bias per se is not part of the scope of this review, it is worth keeping in mind the overall force of these studies, since conscious and unconscious attitudes are certainly shaped at least in part by what people take in from the media.

Unconscious patterns

A variety of reported patterns made use of experimental measures that revealed associations and attitudes we may not even be consciously aware of. For instance:

Automatic responses

At the most fundamental level, there is evidence that the amygdala, a region of the brain that is associated with experiencing fear, tends to be more active when whites view an unfamiliar black male face than an unfamiliar white male face, regardless of their conscious reports about racial attitudes (see Phelps et al., 2000).

Hostility

The “Computer Crash” study mentioned previously suggests that whites, on average, have greater feelings of hostility after seeing the face of an unknown black person, flashed at subliminal speeds, than they do after seeing a white face.

Another experiment involved white participants playing a “Password”-type guessing game. Whenever one player on a two-person team was subliminally primed with a black face, both players on the team ended up exhibiting greater hostility as the frustrations of the difficult game mounted, thanks to a vicious circle in which overall social cohesion, cooperativeness, and benefit of the doubt were hindered.

General negative evaluation

Many studies have confirmed that whites tend to more easily associate positive words (e.g., laughter, peace, joy, friend, wonderful, love, happy, and pleasure) with unknown white faces and negative words (e.g., terrible, failure, horrible, evil, agony, war, nasty, and awful) with unknown black faces, such as in the study reported by Smith–McLallen et al. in 2006.

African Americans’ own implicit biases

Some studies have indicated that many blacks have an implicit bias against unknown faces of their own race, similar to the reactions of whites (e.g., see Livingston, 2002).

Conscious patterns

Whether surprisingly or not, research suggests that the election of Barack Obama does not reflect a sea change in attitudes towards African Americans or racial policies in the United States. For instance, Hutchings concludes that “there is no evidence that White support for racial preferences has changed [between 1988 and 2008].” He bases this conclusion on a comparison between responses in these two years to questions such as whether the Federal government should take more active steps to address unfair treatment of African Americans in the job market. In both years, roughly 90 percent of blacks supported that idea, while roughly 50 percent of whites did. Furthermore, “on matters of public policy dealing explicitly with race, there is little evidence that the racial divide is declining among younger cohorts.” (Hutchings, 2009, p. 929)

Despite the widely held idea that racism has become socially unacceptable, large percentages of the population harbor very traditional prejudiced views in which black males tend more than non-blacks toward violence, criminality, irresponsibility, hypersexuality, and so on.

Note that the companion piece to this social science literature review will assess key patterns in recent polls and surveys, including much more detail on explicit (as opposed to implicit or unconscious) racial attitudes.

Practical Consequences in Lives of Black Males

Usually implicit in the literature, but sometimes explicitly discussed, is the idea that attitudes and biases can lead to real, practical consequences for black men and boys. These attitudes and biases can affect a black male’s fate when it depends on how he is perceived by others, even including other blacks, and on what kind of rapport they have with him.

For instance, attitudes (shaped to some degree by media) can and do:

- directly affect the likelihood of being hired or promoted;

- directly affect the likelihood of school admission;

- directly affect school grades;

- directly affect treatment within the justice system;

- directly affect chances of getting loans;

- end up affecting health and life expectancy;

- end up affecting self-realization and individual development;

- end up affecting the state of social policy (e.g., punitive laws and police practices that impact communities).

Scholars have repeatedly documented the range of implications:

We find that judges harbor the same kinds of implicit biases as others; that these biases can influence their judgment; but that given sufficient motivation, judges can compensate for the influence of these biases. (Rachlinski et al., 2009)

Biased interpretation can have substantial real-world consequences. Consider a teacher whose schema inclines her to set lower expectations for some students, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. Or a grade school teacher who must decide who started the fight during recess. Or a jury who must decide a similar question, including the reasonableness of force and self-defense. Or students who must evaluate an outgroup teacher, especially if she has been critical of their performance. (Kang, 2005, pp. 1518-1519)

[M]ediated images have many impacts on young men of color that work through their effects on White leaders and White citizens. These are people whose decisions on everything from hiring, to granting bank loans, to teaching or medically treating YMC [young men of color], to voting for officials who make public policies, are influenced by their conscious and unconscious racial views. In turn, those policies have important effects on the relationships, careers, and physical and psychological health of men of color during their youth and throughout their lives. There are well-known, self-reinforcing connections that link together under-funded schools in minority neighborhoods, the disappearance of jobs from the same communities due to global and domestic outsourcing, discrimination by employers who assume that YMC applicants are unreliable, higher rates of crime, lower rates of marital stability, and higher levels of medical problems (including premature death). … [M]edia images play an integral role in perpetuating these vicious circles … . (Entman, 2006, p. 21)

The most serious possible consequence of negative attitudes concerns the ultimate questions of life and death. Besides the fact that black men are more likely to be sentenced to death than white men for the same crime, several suggestive experimental studies have shown that subjects in a video police simulation are more likely to “shoot” black men (holding objects that may or may not be guns) than white men under the same circumstances (e.g., see Greenwald, Oakes, & Hoffman, 2003).

Why Media Patterns Are Distorted

Given the long list of negative effects for black males and for society at large, the question remains: “Why does the media perpetuate this destructive set of images and stereotypes?” Racism is often explicitly condemned in the media, yet black males continue to be underrepresented as positive forces in the mainstream, framed in negative ways, offered limited roles in both fiction and news contexts, and so forth. Why? If communicators are to make a positive difference, they must grapple with the roots of the problem.

The recent research on this question is relatively sparse compared to other topics covered in this review, but a number of scholars have offered suggestions about the causal factors that lead to the distortions. Understanding the causes behind these patterns is an important step towards altering them, or at least contending with them more effectively.

Bias among producers of media

The most obvious potential factor is that the people responsible for media content are deliberately presenting a distorted, biased view. This is certainly a historical fact, at least:

The media have not been kind to African American males. Throughout America’s history, black men, teenagers, and boys too often have been depicted as buffoons, criminals, or oversexed animal-like creatures who lust after white women. That followed a design in this country to maintain an inferior, second-class status for black people, dating from slavery on through the twentieth century. (Diuguid & Rivers, 2000)

Scholars have also pointed to a variety of reasons media representations might be biased and distorted, even in the absence of conscious bias or malicious intent on the part of media elites.

Audience preferences

In some cases, scholars assert that viewer preferences drive the distorted portrayals of black males in the media. Most directly, white audiences, according to one perspective, tend only to be comfortable with a certain range of presentations of black males — i.e., presentations that confirm their own fears and prejudices or reassure them that black males are not achieving “undue” power and status.

How does one create and market a product to an audience [i.e., the White majority film audience] willing to pay only to see counterfeit representations of African Americans? (Tucker, 2007, p. 103, drawing on Guerrero, 1993)

Less directly but perhaps equally damaging, the pressures to attract an audience lead to a focus on violence and other attention-grabbing topics, that “happen to be” associated with black males.

These findings [about patterns in news coverage] should not surprise us, given the strong financial incentives to focus on sensationalistic stories such as violent crimes. Financial success of broadcast stations requires high ratings, in order to sell more advertisements at higher rates. … Violent crime news stories frequently involve racial minorities, especially African Americans. (Kang, 2005, pp. 1550-1551)

Incorrect assumptions about what audiences want

If some media content producers are right about what their audiences are interested in, the scholarship suggests that in other cases portrayals of black men are incomplete and distorted because producers of media content have faulty assumptions about demand. For instance, video game developers tend to create game characters that mirror stereotypes of players as young white males, rather than the actual market demographics, which include a significant percent of black men and boys.

[T]he most likely cause for the representation patterns [in popular video games] is a combination of developer demographics [i.e., developers create characters more like themselves] and perceived ideas about game players [i.e., developers create characters that mirror their imagined audience]. (Williams et al., 2009, pp. 830-831)

Lack of input from African Americans

Another clear and compelling hypothesis about distorted media presentations concerns the lack of black input — in various forms — into the production of content. This dearth of representation includes, for instance, limited African-American TV station ownership, and an underrepresentative share of African-American producers, journalists, and experts invited to contribute content.

Perhaps the most important prerequisite to achieving the journalistic ideal of balance is the requirement of having reliable, legitimate, and credible sources competing to advance alternative narratives … contending elite forces working to impose different frames on the coverage of an issue … . (Entman & Gross, 2008, p. 95)

A Knight Foundation report shows that women and people of color continue to be underrepresented in the positions of journalist and editor. Even as other organizations have succeeded in bringing diversity to the workplace, the news media has lagged. In a 2002 census, over 90 percent of journalists were white. (Lehrman, 2005)

Political motivations to traffic in stereotypes

Scholars point out that communicators can score political points, for example, when they promote resentment about social program spending by tapping into racial bias, a kind of generalized “Southern strategy.” For instance, Lucy Williams describes how stereotyped images and misinformation were intentionally inserted into the debate about welfare reform during the Clinton Administration, including:

the use of direct mail scare tactics, the use of the media through televangelists and talk shows… the rightist critique of media as “liberal,” (Herman & Chomsky, 1988), the pressuring of mainstream media through boycotts of advertisers’ products and letter-writing campaigns, (Hardisty, 1995) the encouraging of think tank staff and “scholars” to write op-ed pieces — all toward the goal of “stirring up hostilities” and “organizing discontent” (Smith, 1991). … Right spokespersons became regular media stars and newspaper columnists. (Williams, 1997)

Mistaken understandings

Finally, it is worth noting that people may traffic in these stereotypes simply because they have mistaken impressions of the facts. Without being conscious of biased attitudes, producers of media content of all kinds may, consciously or unconsciously, assume that people with low incomes tend to be black, or looking at this another way, that households with black males are likely to be dysfunctional, that discrimination against black males is limited to isolated acts of racial discrimination, and so on.

2 See also Eschholz et al., 2002.

3 The analysis was based on a review of “over one hundred articles collected by the Center for Media and Public Affairs during May and June of 2004 from newspapers in various parts of the country, from Miami to Seattle to San Antonio to Washington, DC.”

4 See Byrne, 2008.

5 Also see Hawkins and Pingree, 1990.

Download Full Report

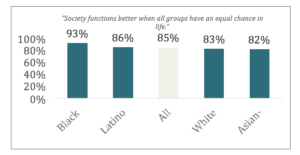

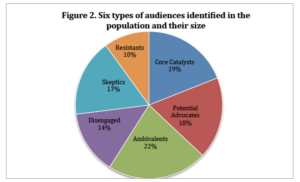

In 2014, The Opportunity Agenda commissioned a groundbreaking nationwide survey to examine what the U.S. public thinks about opportunity in America and to measure public support for policies that expand opportunity across a range of issues, including jobs, education, criminal justice reform, immigration, and housing. Additionally, the research sought to gain a deeper understanding of the multiple factors that influence attitudes on inequality, contribute to an individual’s worldview, and predict people’s willingness to take action on issues they care about. Together, the survey’s findings offer critical insights for social justice leaders and organizations seeking to move hearts, minds, and policy.

In 2014, The Opportunity Agenda commissioned a groundbreaking nationwide survey to examine what the U.S. public thinks about opportunity in America and to measure public support for policies that expand opportunity across a range of issues, including jobs, education, criminal justice reform, immigration, and housing. Additionally, the research sought to gain a deeper understanding of the multiple factors that influence attitudes on inequality, contribute to an individual’s worldview, and predict people’s willingness to take action on issues they care about. Together, the survey’s findings offer critical insights for social justice leaders and organizations seeking to move hearts, minds, and policy.