Our nation aspires to be a place where everyone enjoys full and equal opportunity. Unfortunately, there is a significant gulf between that goal and the daily reality for millions of Americans living in poverty. However, more Americans than at any other time in the past 50 years are ready to hear a new, more accurate story about poverty and to take action to address it. And most Americans—75 percent—think that unequal treatment of poor people is a problem.1

This is an amazing window of opportunity. Yet we need to proceed strategically in our messaging, as these positive attitudes also coexist with longstanding negative stereotypes about welfare dependency, government ineptitude, and irresponsible individual choices, as well as implicit and explicit racial, ethnic, and gender biases. We also face challenges in the form of growing economic inequality, corporate political power, and partisan gridlock on Capitol Hill. We should also be aware that as the economy gradually improves for some groups, empathy for people living in poverty may well diminish.

By combining a sophisticated communications strategy with ongoing research, advocacy, and other approaches, however, we can build public support for transformative change and tackle poverty in our country.

This memo shares what we’ve learned from our research on attitudes and opinions about poverty plus messaging advice for crafting compelling messages about poverty and economic inequality.

10 Tips for Talking about Poverty

- Connect with shared values: Opportunity, Community (Interconnection), Mobility, Security.

- Illustrate systemic causes, including the geography of opportunity.

- Amply document unequal opportunity (not just unequal outcomes).

- Use thematic storytelling with enlightened insiders, affected change agents, group stories.

- Emphasize solutions— contemporary, historic, and visionary.

- Describe the practical and moral societal benefits.

- Be aware of implicit racial, ethnic, gender bias—avoid over-representation and stereotypes, explain current discrimination (including implicit bias).

- Avoid “new poor”/“old poor” false dichotomy.

- Tell a nuanced story regarding the role of government.

- Offer a range of actions, from individual to societal.

Insight from Public Opinion Research

American attitudes toward poverty, poor people, and the role of government tend to be grounded in two competing—but not always mutually exclusive—sets of values: individualism and personal responsibility on the one hand and equal opportunity and interconnection on the other. In fact, people often hold conflicting opinions concurrently. For example, significant majorities of Americans simultaneously oppose cutbacks in aid to poor people and believe that poor people have become too dependent on government assistance programs.

Additionally, our research shows a majority of Americans believe:

- Living standards for the poorest Americans are an important national issue.

- Poverty is mostly due to external circumstances, not lack of effort by poor people.

- The government should do more to reduce the gap between rich and poor.

- Government programs for poor people are a critical safety net that helps people get back on their feet in hard times, and should not be cut.

- Income and wealth inequality hold back economic growth.

- An increased minimum wage, improved education, and college access are important anti- poverty approaches that should be adopted.

Yet, a majority of Americans also:

- Believe poor people have become too dependent on government assistance programs.

- Feel it is not the responsibility of government to reduce the differences in income between people with high and low incomes.

- Believe poverty is an acceptable part of our economic system that does not need to be fixed.

- Are unaware of most structural causes and solutions.

- Hold negative racial stereotypes and beliefs relating to poverty.

Narrative, Messaging, and Storytelling Recommendations

Our research points to a need, as well as an opportunity, for anti-poverty leaders to communicate in new, more impactful ways. Our messaging recommendations include:

- Craft a shared narrative and uplift each other’s voices and concerns. Anti-poverty voices are relatively prominent in the public discourse, but they are diffuse, lacking a coherent narrative that can persuade undecided audiences or counter the disciplined narrative of their most frequent opponents.

- We recommend that while anti-poverty leaders and groups maintain their individual perspectives and priorities, they also craft a shared narrative in which they:

-

- Emphasize the values of equal opportunity and community.

- Highlight systemic causes.

- Describe a path from poverty to economic participation.

- Promote effective solutions and successes.

- Invoke a positive role for government.

-

- Shared messaging should build on public concerns about growing inequality, low wages, and long-term unemployment while educating audiences about less visible forces like racial and gender bias, globalization, and tax and labor policies,

-

- We recommend that while anti-poverty leaders and groups maintain their individual perspectives and priorities, they also craft a shared narrative in which they:

- Avoid the simplistic “new poor”/“old poor” dichotomy. The common storyline in news reporting on poverty is that the newly poor are victims of structural problems with the economy, and are generally viewed sympathetically, while those living in deep poverty (the “old poor”) are poor for other, largely unexplained, reasons. The framing of those stories also tends to reinforce inaccurate stereotypes about poor people, as well as race, and obscures systemic factors that affect both recently and persistently poor people. Communications should move beyond this illusory distinction. Consistent with that approach, stories about the challenges and progress of communities facing deep poverty are needed to ensure a full and accurate picture. Furthermore, the voices of people in deep and persistent poverty need to be heard.

- Document and explain unequal obstacles. Researchers have amply documented the disparate obstacles that contribute to higher poverty rates among communities of color, women, immigrants, and other demographic groups. Yet there is still a dearth of reporting on those dynamics—and for that reason, among others, many audiences are skeptical that such obstacles still exist. Moreover, research and experience show unchallenged subconscious stereotypes will infect attitudes about poverty generally and erode support for positive solutions. Our communications need to both explore and explain this evidence, as well as tell the human stories behind it. A focus on unequal obstacles—not only unequal outcomes or disparities—is an important part of that formula.

- Highlight systemic solutions for systemic problems. While news reports generally ascribe poverty to systemic causes, they do so through fleeting references to general trends such as plant closings, the scarcity of jobs, or the “weak economy.” Few stories explain root causes in any detail, and forces behind the disparate impact of poverty based on race, ethnicity, and gender receive practically no attention.

- However, our research shows that a majority of Americans agree that “the primary cause of America’s problems is an economic system that results in continuing inequality and poverty,”2 so there is an opening for advocates to talk about the systemic underpinnings of poverty and system-wide changes needed to address it. Because Americans are not knowledgeable about effective solutions to poverty, anti-poverty policies and programs that have demonstrable positive results and (research pointing the way to positive outcomes) should be made more visible, as should the positive role that government plays in creating opportunity.

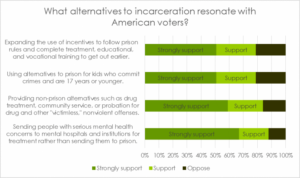

- Build on policies with high levels of support. A number of anti-poverty strategies receive high levels of support from the public. Lifting up these popular solutions while explaining and promoting more complex or less popular ones can help to build broader and more lasting support. Solutions with the greatest support include:

- Raising the federal minimum wage.

- Helping low-wage workers afford quality child care.

- Availability of universal pre-K.

- Lowering the cost of college.

- Show the connections. The idea that we are interconnected and all in this together is crucial to the success of anti-poverty communications. Americans intuitively understand that increasing inequality and poverty hold back the economy and country as a whole and also create an environment in which serious social problems develop and worsen. But their thinking on poverty easily defaults to an extreme “personal responsibility” and “bad decisions” frame. Both showing and telling how we’re all affected and connected—through images, research, spokespeople, and storytelling, as well as specific messaging—is crucial.

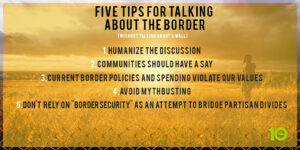

Talking about Race and Poverty

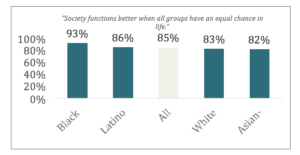

Americans strongly believe that opportunity should not be hindered by race, gender, ethnicity, or other aspects of who we are. However, much of the public is skeptical of the existence of racial discrimination in particular, and negative racial stereotypes about poor people persist among many Americans. For example, in 2010, close to half of the American public (47 percent) agreed that “African Americans have worse jobs, income, and housing than white people because most African Americans just don’t have the motivation or willpower to pull themselves up out of poverty.”3 We need to acknowledge and confront these deep-seated stereotypes.

To do that, our messaging on poverty needs to take into account that race matters in at least four crucial ways:

- Stereotypes and bias warp perceptions of poor people.

- Stereotypes and bias can undermine support for solutions.

- Views and beliefs about poverty differ significantly across demographic groups.

- People’s conscious values on racial equity are generally more positive than their subconscious stereotypes.

Taken together, these trends call for talking about race explicitly and strategically, through the lens of shared values. Keep these guidelines in mind when talking about barriers that hamper opportunity for diverse populations and promoting solutions:

- Show that it’s about all of us. Remind audiences that racial equity is not just about people of color; achieving racial equity upholds our values and benefits our entire society. For example, lax federal regulators allowed predatory subprime lenders to target communities of color, only to see that practice spread across communities, putting our entire economy at risk.

- Over-document the barriers to equal opportunity—especially racial bias. Don’t lead with evidence of unequal outcomes alone, which can sometimes reinforce stereotypes and blame. Amply document how people of color frequently face stiff and unequal barriers to opportunity. For example:

- DON’T begin by discussing the income gap between whites and African Americans

- DO lead by talking about how studies have found that employment agencies frequently preferred less qualified white applicants to more qualified African Americans.

- Acknowledge the progress we’ve made. This helps to persuade skeptical audiences to lower their defenses and have a reasoned discussion rooted in reality rather than rhetoric.

- Present data on racial disparities through a contribution model instead of just a deficit model. When we present evidence of unequal outcomes, we should make every effort to show how closing those gaps will benefit society as a whole. The fact that the Latino college graduation rate is a fraction of the white rate also means that closing the ethnic graduation gap would result in many more college graduates each year to help America compete and prosper in a global economy—it’s the smart thing to do as well as the right thing to do.

- Be thematic instead of episodic. Select stories that demonstrate institutional or systemic causes and solutions over stories that highlight largely focus on individual choices.

- Use opportunity as a bridge, not a bypass. Opening conversations with the ideal of opportunity helps to emphasize society’s role in affording a fair chance to everyone. But starting conversations there does not mean avoiding discussions of race. We suggest bridging from the value of opportunity to the roles of racial equity and inclusion in fulfilling that value for all.

Engaging Strategic Audiences

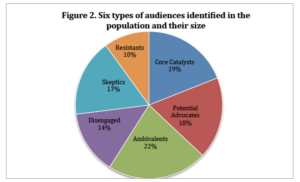

Key to building the national will to address poverty is activating the base of existing supporters while persuading undecided groups over time. That, in turn, requires prioritizing strategic audiences by:

- Activating the base. The most fertile ground for anti-poverty policy and activism lies with Progressives, African Americans, and Latinos. These groups should be prioritized for organizing and calls to action.

- Persuading undecided audiences. Millennials, independent voters, women, and people of faith are disproportionately open and persuadable on poverty issues. White Evangelical Christians, for example, seem to be increasingly in play; 53 percent of them agree that “society would be better off if the distribution of wealth was more equal.”4

- Engaging those most affected. Public opinion research suggests that low-income Americans, while knowledgeable about the realities of living in poverty and interested in change, tend to lack information about structural causes and solutions, and are doubtful about their influence in society. Providing that information, and opportunities for leadership and civic engagement, should be priorities.

Create an Echo Chamber

Traditional and social media trends show a predictable pattern: national election events, the release of census numbers, budget debates, and anniversaries of anti-poverty and civil rights events reliably increase attention to poverty. Demonstrations, strikes, and major think-tank reports also frequently generate media interest.

We recommend that anti-poverty communicators:

- Chart these “news hook” events well in advance.

- Prepare a multi-platform media strategy that is proactive, builds upon the activity of high- profile voices, and lifts up the voices of those most affected.

- Be more intentional and collaborative about sharing and jointly promoting new research and activities across the field.

These efforts should complement rapid-response communications when relevant, but unpredictable, events occur.

Every couple of generations, national values, demographic change, attitudes, and experiences converge to create the potential for transformative social change. We must leverage this moment of profound public openness to shift the discourse around poverty to change hearts, minds, and policy.

Build a Strategic Message

One formula for building an effective message is Value, Problem, Solution, Action. Using this structure, we lead with the shared values that are at stake, outline why the problem we’re spotlighting is a threat to those values, point toward a solution, and ask our audience to take a concrete action.

- Lead with values. Most communicators agree: people don’t change their minds based on facts alone, but rather based on how those facts are framed to fit their emotions and values. Shared values help audiences “hear” messages more effectively than do dry facts or emotional rhetoric.

- This country is built on the idea of opportunity for all, regardless of where you come from or what you look like.

- Our economic policies should be propelled by the values of accountability, economic security, and opportunity for all, not greed, privilege, or the interests of a few.

- Introduce the problem. Frame problems as a threat to your vision and values. This is the place to pull out stories and statistics that are likely to resonate with the target audience.

- But that’s far from what we’re seeing today, with working Americans’ living standards declining and the richest 1% holding 40% of the nation’s wealth.

- Pivot quickly to solutions. Positive solutions leave people with choices, ideas, and motivation. Assign responsibility—who can enact this solution?

- Reclaiming the promise of opportunity means demanding an economy that works for everyone, not just the richest members of society. Corporations need to pay their fair share, and banks need to invest in building up communities sustainably.

- Assign an action. Try to give people something concrete they can picture themselves doing: making a phone call, sending an email. Steer clear of vague “learn more” messages when possible.

- Join us by [include a concrete action that your audience can take].

Say What You’re For, as Well as What You’re Against

Anti-poverty advocates may not share a single list of policy demands, but we can and should paint a positive picture of the society we’re trying to create. Most people already have a lot to worry about, and are in no mood for problems with no solutions in sight. We can cut through the clutter of stories about how bad things are by painting a picture of what our country would look like if it embraces and promotes:

- Opportunity: for honest work that pays a decent, living wage.

- Accountability: with fair rules, enforcement, and prosecution where appropriate of the corporations and individuals who lawlessly wrecked our economy.

- Fairness: including a tax system in which the wealthiest companies, millionaires, and billionaires contribute their fair share to the nation that gives them so much.

- Voice: a political system in which every American’s voice and vote are equal, and large sums of money are not allowed to corrupt the democratic process.

- Economic Mobility: access to an affordable college education for everyone who has the ability and desire to attend, without the crippling burden of loan debt.

- Economic Security: including a halt to unnecessary foreclosures, the restoration of devastated neighborhoods, and reductions in mortgage payments to fair, realistic levels.

Notes:

- The Opportunity Agenda, Opportunity Survey: Understanding the Roots of Attitudes on Inequality, 2014.

- Public Religion Research Institute, American Values Survey, September 2012.

- Gallup/USA Today poll, June 2010.

- Public Religion Research Institute, American Values Survey, September 2011.