| Upholding Our Values | A Commonsense Approach | Moving Forward Together |

| Most audiences believe that protecting basic rights like due process in the legal system are central to preserving and upholding American values of security, fair treatment, and freedom from government persecution. This embrace of due process as integral to our nation’s identity is an opportunity to tell a story of American values in peril, and to make the case for how to protect and restore them through a commonsense approach to our immigration policies. | Most voters want enforcement that both upholds our values (protecting due process, rejecting racial profiling, ensuring a border free of human rights violations) and is practical. While cuts are made in military and education budgets, Americans do not favor costly increases in enforcement and border security. In addition, many respond to the argument that focusing on federal policy reform will alleviate many of the pressures that the border currently faces. |

We should emphasize our shared interests and discredit “us vs. them” distinctions, and talk about how protecting basic rights is part of our American identity and matters to us all. Because we’re all connected, bad policies hurt us all – threatening our values and disrupting our communities. |

| Due process is a human right central to the American justice system. American values of justice and fairness only stand strong when we uphold the right to due process.

Due process – access to courts and lawyers and a basic set of rules for how we’re all treated in the justice system – is a human right and central to our country’s values. We should reject any policies that deny due process for undocumented immigrants or anyone else. Our American values of justice and fairness only stand strong when we have one system of justice for everyone. If one group can be denied due process, none of us will be safe to enjoy the rights that America stands for. America is a nation of values, founded on an idea: that all men and women are created equal. We hold these truths to be self-‐evident: that all people have rights, no matter what they look like or where they came from. So how we treat new immigrants reflects our commitment to the values that define us as Americans. We need a commonsense immigration process, one that includes a roadmap for people who aspire to be citizens. When it comes to our outdated immigration laws, we need real solutions that embrace fairness, equal treatment, and due process. Current laws are badly broken, but disregarding our values is not the answer to fixing them. Tell Congress it’s possible-‐-‐and imperative-‐-‐to both modernize our immigration laws and protect our core values at the same time. |

America deserves a commonsense immigration process that creates a roadmap to citizenship for 11 million new Americans who aspire to be citizens. Legislation must also keep families together here in this country, protect all workers, and honor and preserve our longstanding constitutional promise of equal treatment for all.

The roadmap to citizenship must not be so expensive and onerous that it leaves millions in limbo for lengthy periods of time, subject to an ever moving metric of “border security.” We need a fair system that creates a reasonable immigration process for New Americans. A roadmap to citizenship is imperative, but must not be done at the expense of border communities, who have endured years of border security “enhancements,” including more agents, drones, military presence and walls. We need commonsense immigration policies, not an escalation of border militarization, more detention and arrests, and policies that promote racial profiling – a harmful and ineffective practice based on stereotypes. We need border security that involves and enlists border communities in providing for safe borders in ways that respect their human rights and constitutional rights and treat everyone fairly. For too long, our immigration policies have moved into the realm of criminalization – needlessly imprisoning people in the for-‐profit prison industry. We need to step back and think about what our immigration policies should do for us: create a reasonable process for immigrants to come here, keep families together, and respect human rights. |

We are a country that values due process, fair treatment under the law, and a commonsense approach to the issues facing our communities. Our immigration policies must reflect those values. If we allow anyone’s due process rights to be violated, if we detain anyone indefinitely and without representation, if we give into rash, unworkable policies – we all lose.

We are all better off when our communities are healthy and strong, we feel safe, and our children can thrive. As women and mothers, we know the importance of working to build strong communities and families, and being good neighbors who help each other. As Americans, we all do our part to contribute, and we’re all the better for having hardworking new immigrants as members of our communities [by being customers in our stores, giving to local churches and charities, and participating as parents in our schools]. That’s why we need an immigration process that strengthens, not divides, our communities. We need our immigration policies to uphold our values and move us forward together. When they result in splitting up families, imprisoning people, deporting those who have lived here for years and are part of the fabric of our communities, they are not serving any of us. We live in a democracy. That means we have the power and responsibility to change laws that don’t work. As Americans, we’re all in it together, and we’re stronger when we focus on what unites us rather than our differences. Our immigration policies must reflect those values. That’s why any immigration proposal should insist on fair rules for all American workers and families, and include a roadmap to citizenship for aspiring citizens who want to share in the American Dream. |

Messaging And Report Category: Messaging Memo

Talking About Magner v. Gallagher

On February 10th, the City of St. Paul, MN withdrew its petition to the U.S. Supreme Court in Magner v. Gallagher, a potentially important fair housing case. Under Supreme Court rules, this action should soon result in an order ending the case and reinstating the decision below by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit. In its now-withdrawn petition, St. Paul had argued that the Fair Housing Act outlaws only intentionally discriminatory housing practices, but not policies that unnecessarily discriminate in practice. The 8th Circuit Court of Appeals disagreed, as has every court of appeals to have considered the question. And a range of state attorneys general, fair housing groups, civil rights organizations, and housing industry leaders had submitted briefs on the other side, arguing that prohibiting both kinds of discrimination is what Congress intended, and is crucial to equal opportunity in America. In changing its position, the City of St. Paul now agrees; its public statement declared that if the Supreme Court were to have ruled too broadly in its favor, the result would have been to “undercut important and necessary civil rights cases throughout the nation. The risk of such an unfortunate outcome is the primary reason the city has asked the Supreme Court to dismiss the petition.”

Public Opinion on Equal Opportunity and Housing:

While there is little opinion research specific to the subject of fair housing, a large body of polling and focus groups1 on race, equal opportunity, and housing points to several persistent trends:

- Americans believe strongly in the value of equal opportunity, but are frequently skeptical that inequality of opportunity and, particularly, discrimination still exist — with white Americans being most skeptical on average, and African Americans the least skeptical.

- Americans of all races and ethnicities tend to start from the perspective of personal responsibility and the “self-made person,” and assume that unequal outcomes are largely the result of differences in individual effort and personal decisions.

- The public’s default understanding of discrimination relates to overt, individual bigotry; structural and institutional barriers to fair housing are largely invisible to most Americans.

- Americans are increasingly comfortable and desirous of living in racially and ethnically diverse communities, but are still resistant to integration with immigrants. And different groups prefer different levels of diversity.

- The values and themes of opportunity, interconnection, ingenuity, and the common good tend to be especially resonant across audiences when it comes to civil rights remedies.

This is an important moment to praise St. Paul’s decision as the right one, and to reinforce why the Fair Housing Act properly prohibits the full range of housing discrimination in America. This memo recommends ways of talking about this case that can build understanding and support for robust fair housing enforcement that prohibits unnecessary discriminatory effects. It is aimed at talking to “persuadable” audiences who are not yet fixed in their opinion. Our advice draws on existing public opinion research, analysis of media coverage, and communications experience.

I. Framing and Narrative

We believe this case and its resolution should be framed in terms of America’s interest in protecting equal opportunity and freedom from discrimination for everyone, a responsibility that benefits all of us and is shared by cities and states around the country. We should describe as common sense the notion that all forms of avoidable housing discrimination should be set aside to allow more fair and effective solutions. And we should make visible the structural and institutional barriers to fair housing, like unreasonable zoning restrictions that limit the options of all working Americans while especially excluding people of color.

Magner was a case in which landlords were trying to provide affordable housing to a diverse range of working-class tenants. They claimed that the city (St. Paul, MN) was hampering their efforts through extreme and allegedly false code enforcement, motivated by a predisposition against multi-family housing. If their story is accurate — a question that will now be determined at trial — then the city’s actions do violate the Fair Housing Act. Policies that serve no important purpose, yet discriminate in practice, should fail under the Fair Housing Act.

Opponents will try to describe the disparate impact standard as affirmative action (which it is not), as well as “racial bean counting” and closet “quotas.” With the public and the media, it is important to avoid arguing within that frame, but rather, to use our own frame of protecting fair housing and equal opportunity for all.

For example:

- “This case was about the obligation of cities and towns to protect equal opportunity in housing. That includes avoiding unnecessary policies that discriminate in practice, as well as those that are intentionally discriminatory. St. Paul did the right thing by embracing that responsibility.”

- “If a policy unnecessarily excludes people of a particular racial or ethnic group, or families with children, for example, it’s common sense that it should be set aside in favor of one that accomplishes the same goal fairly, effectively, and without discrimination. That’s been the law for over forty years, and it’s appropriate that it will continue to be the law.”

- “Governments have a responsibility to ensure equal opportunity and freedom from discrimination for everyone. That requires watching how different policies play out on the ground. When a city or town has evidence that a particular policy — like a zoning ordinance or uneven enforcement of housing codes — is likely to be discriminatory, it has a responsibility to reexamine or abandon that process and find one that’s fair and effective.

A longer-form narrative along these lines might include the following:

“Equal opportunity is a bedrock American principle, and critical to our national success. But despite the progress we’ve made as a nation, significant obstacles to equal opportunity still exist, particularly when it comes to housing and homeownership. There are still some real estate agents, landlords, and others who practice intentional discrimination against people of color, families with children, people with disabilities, and other Americans. But more often these days, local governments and real estate corporations engage in unjustified and unnecessary practices with the practical effect of discriminating against well-qualified Americans. Some cities and towns, for example, prohibit the building of smaller homes or apartments that working people could afford, which in many places excludes most people of color. That means certain Americans are unfairly and unnecessarily cut off from opportunities like quality schools, jobs, and business possibilities. That’s bad for all of us, and we applaud St. Paul — and every court of appeals that’s considered the question — for helping to uphold protection against that harm.

II. Recommended Do’s and Don’ts

Research and experience provide some Do’s and Don’ts for talking about the case with media and public audiences:

Do lead with values, particularly:

- Opportunity — Everyone deserves a fair chance to live in the neighborhood of his or her choice, free of unnecessary barriers.

- Equality — What you look like or where you come from should not determine the housing you have access to.

- Fairness — Unnecessarily excluding Americans of a particular racial group from a town or neighborhood is unfair as well as unwise.

- The Common Good — Protecting fair housing strengthens our communities and our nation.

Don’t use jargon or legalistic language, like:

- “Shifting burdens of proof,” “strict scrutiny”

- “Validity,” “standard deviations,” “metropolitan statistical area”

Do use plain language and straightforward ideas that all audiences can understand:

- “Equal opportunity”

- “Setting aside policies that are unfair and unnecessary”

- “Fair and effective”

Don’t imply that disparate impact discrimination is somehow a lesser violation, less harmful, or of less concern than is intentional discrimination.

Do acknowledge the progress America has made toward equal opportunity, while documenting today’s remaining barriers and obstacles.

Don’t talk with general audiences in terms of the rights of any one group — e.g., African Americans, Latinos, people with disabilities — making the case an “us vs. them” proposition.

Do talk about equal opportunity and fair housing for all, the importance of rooting out unfair and unnecessary barriers to equal opportunity, and the shared benefits of fair housing and inclusive communities.

III. Possible Answers to Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why is resolution of the case important?

A: This positive resolution of the case is important because overcoming unnecessary and unequal barriers to housing is crucial to ensuring equal opportunity for all and to building strong communities. Thanks to St. Paul’s action, we can be confident that that progress will continue.

One of the reasons why the Fair Housing Act’s full reach is so important is that it’s the primary tool to hold banks and subprime lenders accountable for abusive lending practices. The lending industry knows this, and that’s why the biggest banking organizations in the country signed briefs asking the Court to narrow the Act’s reach. The positive resolution of this case means that subprime lenders and other exploitative actors can be held accountable for racial discrimination.

Q: What is disparate impact?

A: Disparate impact is the idea that some policies have the practical effect of discriminating based on race, family status, or some other category, and are unnecessary or unjustified.

When a policy has a discriminatory effect and it is unjustified or unnecessary, the disparate impact approach says it must be set aside in favor of a policy that is both fair and effective. But if the policy has a solid reason behind it, and no other policy could achieve the same goal with a less discriminatory effect, then the challenged policy stands, even though it excludes more people from one group than another.

An example is when a city decides to keep out all housing that would be affordable to working-class people, and that has the effect of excluding most or all people of color, who are more likely to be in that category. If the city could not show an important reason for its policy, or if a more fair and effective alternative were available, then the policy would have to be set aside under the disparate impact approach.

Another example would be if a rental company decided to rent only to people from a particular zip code, and that zip code included very few people of color or families with children, compared with the larger community. If the company could not justify its policy, or if a less discriminatory approach could accomplish the same goal, then the Fair Housing Act would require a change.

Q: What were the facts of the Magner case?

A: The plaintiffs in the case were building owners in St. Paul, Minnesota who rent their properties to working-class people, including many African Americans. They claimed that the city was trying to push them and other rental owners out of town, in favor of owner-occupied housing, with the practical effect of excluding many African Americans from any housing in the city.

Q: Shouldn’t a city be able to enforce safety and cleanliness standards?

A: Cities and towns should be able to enforce fair and legitimate safety and sanitation standards. The claim here was that the enforcement of those standards was both discriminatory in practice and unnecessary in fact. If the plaintiff apartment owners can’t prove those two things at trial, then they ought to lose their fair housing claim. But if their claims have merit, they should win.

Preserving the American Dream for All

This memo offers communications ideas and guidance around messaging to promote an equitable economic recovery that includes all Americans. It is based on analysis of recent public opinion research and media coverage on economic issues, as well as strategic communications principles.

To ensure that we create and sustain an economy that works for everyone as we emerge from the economic crisis, we must make the case to the American people that recovery efforts should be equitable, fair, and transformational. To move the national conversation toward support for an equitable economic recovery, we recommend a shared narrative that emphasizes restoring the American Dream through commonsense policy solutions that strengthen our country by creating economic opportunity for all.

Lead with Values

Primary Values:

- Opportunity and Equality: Everyone deserves a fair chance to reach his or her full potential, and what you look like or where you live shouldn’t determine the benefits you receive or burdens you bear in society.

- Community and the Common Good: We’re all in it together, and we all share responsibility for the good of our society.

- Security: We should all have the basic tools and resources to provide for ourselves and our families.

Secondary Values:

- Mobility: Where you start out in life should not determine where you end up.

- Redemption/Renewal: People grow and change, and deserve a second chance after missteps or misfortune.

- Voice: We should all have a say in decisions that affect us.

- Accountability: People, institutions, and government must act responsibly and be answerable for their actions. Use this value with care, as it can be turned around to focus on individual actions and punishment to the detriment of our larger messages.

Organize Messages Around a Core Narrative

To shape public dialogue, we have to tell a bigger story, rooted in shared values, that engages the American people as well as policymakers. To create such a narrative we recommend using the following broad themes to paint a larger picture about why equitable economic recovery matters for us all.

- The American Dream. This country stands for opportunity. We need to focus on expanding opportunity, not restricting it or allowing historic barriers to foster inequality among us. The American Dream is central to our country’s success, and we can’t let the current economic crisis force it into obscurity. Economic security and stability, too, are crucial to securing the Dream for ourselves and future generations.

- Solutions. We have emerged from crises before by relying on American ingenuity and know- how, so it is within our power as a people not only to bring our economy back from this recession but also to tackle the inequalities that excluded many communities before the downturn began. We need to move forward, with government paving the way, on a commonsense, practical agenda that expands opportunity for everyone here.

- The National Interest. The causes and effects of this economic crisis have illustrated how we are truly all in this together. When we allow inequality to fester and harm whole communities within our national fabric, it weakens us all. Recovery needs to be about mending and strengthening the entire cloth, so that we are prepared to face the future together.

Additional Themes and Considerations

Jobs, Jobs, Jobs. The public, policymakers, and the media are all hyper-focused on unemployment and want to know that any potential policy solution will address that situation. We can leverage this concern by highlighting the need for good jobs that will support America’s families, and by pointing out that creating jobs should be a top priority, even over deficit reduction for the time being.

A positive role for government. Talking about government can be tricky, given the popular narrative of “big government’s” inability to solve problems. But holding up the government’s regulatory and investment role, as well as its past successes, is crucial to building support for further intervention. For instance, we should make the point that economists agree that government intervention in the form of the stimulus has actually been successful, if insufficient. Other ways to talk about government include:

- Public structures

- Protector of opportunity

- Planner for the future

- Connecter of Americans

- “Paving the way” for enterprise and innovation.

Acknowledge progress on equal opportunity, while over-documenting the barriers left to address. Whenever we talk about inequalities, it is important to talk about the positive steps we have made in this country as well as where we need to go. The election of an African American president, among other things, convinces some that our work to address inequality is done. We need to explain why and how this is not the case, providing solid data and examples showing the barriers to opportunity and how we can knock them down.

Tell thematic stories, connecting human stories to systemic problems and solutions. Show how we’re interconnected across communities, groups, and systems. Without sufficient context, audiences can limit a story’s implication to the individual level, attributing successes and failures to personal responsibilities and actions that have little to do with the system-level change we are seeking in our immigration system. We therefore suggest balancing powerful individual stories with the systemic implications they help to illustrate. Doing so highlights the solutions we are hoping the public will embrace.

Frame the opposition. While we do not suggest leading with divisive rhetoric, it is important to have messages ready to show the contrast between our approach and solutions, and those who oppose them. When doing so, we can make the case that our opponents are focusing more on anger than solutions and are divisive, impractical, and partisan—too much anger, too few solutions. Their approach can be described as promoting a “you’re on your own” mentality, as well as short-sighted ideas that are counter to our national interest, and out of touch with everyday Americans.

Themes to Avoid

Avoid trashing government as inherently ineffective or corrupt. We need to restore the public’s faith in government and effective government solutions, not fuel the fire. Instead, talk about an American can-do attitude and how government can support it.

Avoid leading with divisive rhetoric or accusations of racism, which are unlikely to start a productive conversation with persuadables. Instead, talk about the American Dream and how inequality, particularly that which is based on what we look like or where we come from, is a threat to it.

Avoid using a colorblind frame. We want to emphasize that we need an economy that works for all, but that does not mean that the solutions can be one-size-fits-all. Different communities were at different levels of disadvantage before the crisis, so boosting everyone in the same way will only exacerbate those existing inequalities. This both violates our values and hurts the entire country. We need to address the cause and effect of historic, and recent, barriers to opportunity.

Avoid raising the threat of crime or violence due to tough economic times. This just reinforces unhelpful stereotypes about low-income and poor people. Instead, lead with the need for investments in education and other public structures, which benefit our communities.

Avoid competition for scarce resources, or “leveling the playing field,” which underscores the notion that someone has to win, while others lose. We need to find solutions that work for everyone. There is room, however, to talk about how greater and more equal opportunity will serve the nation’s need to compete in a global economy.

Avoid emphasizing punishment for irresponsible behavior. While it is true that those responsible for the economic crisis should be held accountable, making this a main theme of communications can backfire, as many have tried to shift blame to low-income communities and people of color. Instead, emphasize the need for commonsense regulation to prevent future crises.

Avoid myth-busting. There is a lot of misinformation in the public dialogue about the crisis and its causes. Some have attempted to blame poor people’s desire to own homes, for instance. However, there is evidence that simply refuting an assertion will not change people’s views and can instead further implant the wrong information in their minds. Worse, restating a myth can plant it for the first time with those who have not heard the misinformation before. An affirmative approach that states the real facts about the causes of the economic crisis is more effective.

Applying the Message

In order to deliver a consistent, well-framed message in a variety of settings, we recommend building messages by including Value, Problem, Solution, Action elements. Leading with this structure can make it easier to transition into more complex or difficult messages.

Value:

Keeping the ladder of opportunity sturdy for everyone in our country is crucial to America’s future, and to a lasting economic recovery.

Problem:

But despite the progress we’ve made toward equal opportunity for all, far too many Americans are unplugged from decent jobs, fair mortgage lending, or a shot at running a business. For instance, women in our state earn just 77¢ for every dollar that men earn, and women of color earn only 66¢ per dollar. That’s bad for our economy, and contrary to our national values.

Solution:

Commonsense laws that protect equal opportunity are one important way to ensure that everyone has a chance to achieve economic security and contribute to our region’s economy. We should adopt those laws, along with others like loan counseling and worker re-training that also strengthen our economy.

Action:

Host a community meeting or write a letter to the editor supporting an Opportunity Action Plan for our state, including strong equal opportunity protections.

Talking Point Suggestions

Our country is strongest when it protects opportunity for all. Recovery efforts need to focus on how to preserve and promote the American Dream for everyone. Anything less is bad for all of us.

We need an economy that works for everyone, with new, fair rules for a 21st century reality. This is about investing in our nation’s future. Turning back the clock to pre-crisis conditions is not sufficient; we need a transformational recovery that moves all communities, particularly those that were hurting before the downturn even began.

America has the know-how to find the right solutions for the economy, and we have the determination to topple the barriers to full and equal opportunity. We have to renew our commitment to tackling these tough problems while redoubling our efforts to preserve our ideals of equality and a fair chance for everyone.

It’s time for innovative, practical solutions that work, not divisive politics. Research and experience show what works in this area and what doesn’t. Economists agree that we need to tackle jobs and the recession first, then turn to the deficit. The best way to reduce the deficit is to put Americans back to work, so they can buy goods and pay taxes.

TALKING EQUITABLE ECONOMIC RECOVERY AT-A-GLANCE

- Lead with values. Primary: Opportunity, Community/Common Good, Security. Secondary: Mobility, Redemption/Renewal, Voice, Accountability (use with care)

- Organize messages around a core narrative focused on The American Dream, Solutions, and the National Interest.

- Focus on jobs: Investment in quality jobs over immediate deficit reduction.

- Acknowledge progress on equal opportunity, while over-documenting barriers.

- Emphasize Government as a connector, planner, able to pave the way for progress.

- Tell thematic stories, connecting human stories to systemic problems and solutions.

- Frame the opposition’s solutions as divisive, impractical, and out of touch.

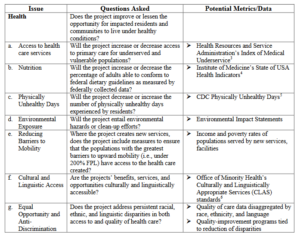

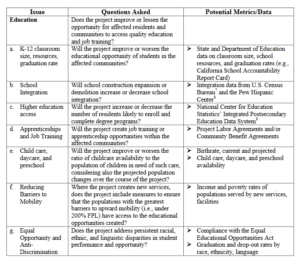

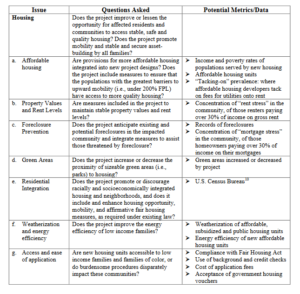

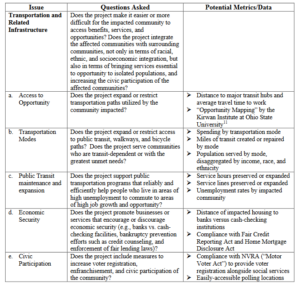

Indicators to Evaluate the Opportunity Impacts

Introduction

This memorandum recommends and discusses indicators to be used in evaluating geographic access to opportunity, including available sources of relevant data. We propose that these indicators be integrated into Department rules regarding the duty to affirmatively further fair housing.1

Opportunity is the idea that everyone deserves a fair chance to achieve his or her full potential. Ideally, all people in the United States should have equal access to opportunity—which includes personal and economic security and healthy living conditions—without regard to where they live. In practice, however, our neighborhoods are the primary environments in which we access key opportunity structures such as high-performing schools, sustainable employment, safe neighborhoods, and health care, and those structures are too often unequal across neighborhoods and communities.2 Conversely, place-based investments in greater and more equal opportunity can have lasting, intergenerational impacts on the life outcomes and prosperity of individuals, communities, and whole regions.

Under the Fair Housing Act,3 the Department of Housing and Urban Development (“HUD”) has a duty to “administer the programs and activities relating to housing and urban development in a manner affirmatively to further the policies of [the Fair Housing Act].”4 The “affirmatively further fair housing” (“AFFH”) obligation requires HUD to do something “more than simply refrain from discriminating . . . or from purposely aiding discrimination by others.”5 Instead, HUD has an affirmative obligation to “provide, within constitutional limitations, for fair housing throughout the United States”;6 to “remove the walls of discrimination which enclose minority groups”;7 and to foster “truly integrated and balanced living patterns.”8 In other words, the Fair Housing Act requires HUD proactively to promote non-discrimination, residential integration, and equal access to the benefits of housing—that is, to opportunity as it relates to geography.

To achieve greater and more equal opportunity for all people in the United States, and as an addendum to our suggested reforms of HUD’s AFFH regulations,9 this memorandum sets forth the specific indicators of opportunity that we believe should be used to evaluate proposed and ongoing housing and urban development projects and activities. Our recommendations are based on a large body of social science research, legal precedent, and consultation with national experts. The indicators of opportunity that we have identified, and that we explore in further detail in this memorandum, are:

- Access to high-quality education (measured by the percentage of students eligible for free lunch, math and reading test scores, and high school completion rates).

- Concentration of poverty within a neighborhood (measured by the Federal Poverty Level (“FPL”) and considering the measure of income adequacy within a neighborhood).

- Racial segregation within a census tract or neighborhood (measured by variation from the proportion of the non-white population regionally).

- Environmental quality within a particular neighborhood (measured by the Toxic Release Inventory and the National-Scale Air Toxics Assessment).

- Access to health care (measured by data on health disparities from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and correlated to neighborhoods through their mapping software).

- Access to sustainable jobs (measured by data from the Census Zip Business Patterns and the Bureau of Labor Statistics).

- Crime rates (measured, to the extent possible, by data from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports and statistics provided by local police departments).

In this memorandum, we also discuss transportation-related indicators as subsets of both our environmental quality and our access to sustainable jobs indices.

Although this memorandum discusses each of the enumerated factors in a separate section, in practice, it is unwise to view any of the factors in isolation.10 Thus, to evaluate a housing or urban development project’s impact on opportunity within a given region, the evaluating body should measure the project’s effects in light of the aforementioned criteria and favor projects with the greatest opportunity yield, based on the totality of the circumstances.

If funding is contemplated in a metropolitan area in which the neighborhood markers of low- opportunity noted in this memorandum are met (e.g., a 20% concentration of poverty within a neighborhood, calculated based on the percentage of people within the neighborhood living at 150% of the FPL; a school system scoring more than two standard deviations away from the national averages in math and reading test scores, percentage of students eligible for subsidized meals, or high school completion rates; or a finding of 60% racial segregation within a neighborhood, calculated based on the racial dissimilarity index), these existing markers of low- opportunity should flag for the funding agency that all projects within its jurisdiction warrant closer scrutiny of the project’s ability to increase opportunity within the region. Conversely, there should be a presumption against federally assisted activities that increase the concentration of low-income people, racial, or ethnic populations in low-opportunity neighborhoods.

In the second assessment, the proposed project and any alternative suggested projects for which the funding could be allocated should be weighed against each other, based on the opportunity indicators presented in this memorandum.

Because these indicators are organized beginning with the factors with the strongest correlations to expanded opportunity (i.e., education, concentration of poverty, and racial segregation) and ending with the factors that are shown to correlate, but not as strongly, to opportunity (i.e., access to jobs and crime rates), these factors should be weighted accordingly in the evaluation calculus.

By necessity, the evaluation task requires some flexibility and adaptation to practical circumstances (e.g., a project concerning senior citizens may warrant placing greater weight on a community’s access to health care, rather than on its impact on the community’s access to education). In any evaluation, however, the evaluating body should be required to have a justification available of its calculus, in writing, based on legitimate, nondiscriminatory reasons.

The data necessary to measure the impact of federal funds on opportunity in housing and community development projects is, for the most part, already available nationwide at smaller levels of geography (generally by census tract, zip code, or political jurisdiction). Most of the data we suggest assumes the use of census tracts to approximate neighborhoods within a metropolitan area. However, government entities should consider any local data that is available if such data provides a more accurate method of defining neighborhoods.

Methodology

In addition to The Opportunity Agenda’s ongoing research regarding the status of opportunity in the United States generally,11 we identified opportunity indicators specific to the context of housing and neighborhood development by a review of the dominant literature in these areas and discussions with leading experts and researchers in the field. In addition, our memorandum gives significant weight to the findings of a report produced by the What Works Collaborative,12 entitled, “Building Environmentally Sustainable Communities: A Framework for Inclusivity,”13 which we found to be particularly insightful and salient on the question of opportunity indicators in the context of neighborhood development.

Opportunity Indicators

1. Education

Access to quality education is one of the strongest predictors of opportunity in the United States. As Chief Justice Earl Warren stated in Brown v. Board of Education, “it is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education. Such an opportunity, where the state has undertaken to provide it, is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms.”14

The duty to affirmatively further fair housing has always been intimately tied to the obligation to ensure equal access to educational opportunities. For example, the Fair Housing Act creates presumptions against locating housing projects in segregated neighborhoods,15 and an explicit part of that analysis is a consideration of the racial composition of local schools.16 Furthermore, a number of housing experts have detailed the reciprocal relationship between fair housing policies and school integration (which has well-documented effects on the quality of education for students).17 Educational quality should thus be a high priority indicator of access to opportunity stemming from housing and urban development decision-making.

Our research indicates that the most consistent measurements of educational opportunity at the neighborhood level are:

- Student poverty concentration (measured by the percentage of students eligible for free and reduced-price lunch);

- Aggregate student test scores (e.g., the percentage of students passing standardized reading and math tests); and

- High school completion rates.

Student Poverty

The socioeconomic make-up of a school’s student body is the greatest external predictor of student success and achievement.18 One illustrative study analyzing data provided by the U.S. Department of Education’s School-Level Achievement Database found that a predominantly middle-class school is twenty-two times more likely to be consistently high performing than a high-poverty school.19 Conversely, research by The Century Foundation found that, on average, low-income students attending middle-class schools perform higher than middle-class students attending low-income schools.20

The percentage of students in a public school receiving subsidized meals has been used by experts as a reliable proxy for student poverty.21 At the national level, this data is available from the National Center for Education Statistics Common Core of Data (“CCD”).22 At the state level, it is typically available directly from each state’s Department of Education. This data may also be found on School Data Direct,23 a web-based source of school and district data, with searching, comparison, and downloading features.

Student Test Scores

Research has indicated that differences in educational attainment and standardized test scores account for most of the differences in subsequent hourly wages.24 According to ongoing research by the Kirwan Institute, a neighborhood’s average test scores have been shown to highly correlate with opportunity outcomes.25 Reading and numerical skills, in particular, must be taken into account because the differences in scores on reading and math tests account for much of the subsequent differences in earnings and employment probabilities.26

This data can be found on School Data Direct,27 as well as the National Center for Education Statistics CCD.28

High School Completion Rates

High school completion rates are an important opportunity indicator and, conversely, high dropout rates are linked to significant barriers to opportunity. With a more educationally demanding economy, the effects of dropping out are more negative than they have ever been, especially for people of color.29 Additionally, women who have not finished high school are

much more likely than others to be on welfare, while men who have not finished high school are much more likely to be incarcerated at some point in their lives.30 Dropout rates at the school level have shown a strong correlation with opportunity outcomes in some metropolitan areas.31

National completion rates may be derived from National Center for Education Statistics data by calculating the number of students in a graduating class divided by the number of students in grade 9 three and a half years earlier, the same formula may be used at the school level to determine dropout rates,32 based on data found on School Data Direct. At the state level, completion rates are typically available from the state’s Department of Education.33

Pragmatic Considerations

Because the education data on School Data Direct is available at the school level, and any funding-allocation decisions for housing projects are typically made on a jurisdiction-wide or metropolitan-wide basis, we support the methodology used by the What Works Collaborative, in matching school level data to census tracts. In a report entitled, “Building Environmentally Sustainable Communities: A Framework for Inclusivity,” the What Works Collaborative states:

In order to match census tracts to schools, we draw Voronoi polygons separating elementary schools, creating what are in effect model catchment areas. We then measure the intersections of each census tract with those Voronoi polygons by land area to estimate the educational opportunity offered in each census tract. In cases in which multiple polygons overlap with a census tract, we weight those multiple values by the percentage of the census tract covered by each polygon. By doing so, we are able to calculate the average public elementary school opportunity that a resident of this census tract faces, using free and reduced-price lunch data and 4th grade math and reading test score data. We choose 4th grade data because it is universally available under No Child Left Behind.34

Specific Educational Considerations for Individuals with Disabilities

Expanding opportunity for all, particularly through housing and urban development projects, necessarily requires specific consideration of the needs of people with disabilities. Congress recognized the need for this special focus and enacted the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (“IDEA”), in part, to improve educational results for children with disabilities, and to ensure equality of opportunity, full participation in society, independent living, and economic self- sufficiency.35

One way that the IDEA measures equal access to education is through the ability of disabled students to access the general education curriculum in the mainstream classroom to the maximum extent possible.36

In implementing HUD’s AFFH regulations, school systems that best support equal access to education for disabled and nondisabled students should typically be favored for project funding. Access to equal education for people with disabilities may be measured by how much time disabled students spend in the mainstream classroom and the graduation/dropout rates.37

Monitoring the graduation rates of children with disabilities will help determine the necessary transition services that will promote successful post-school employment or educational opportunities, which is an important measure of accountability for individuals with disabilities.38 Indicators such as transportation and concentration of poverty for individuals with disabilities are often embedded within the issue of access to educational equity.

Note, however, that there are a number of special challenges and limitations to data collection for individuals with disabilities.39 Consistent, reliable data is difficult to find, especially regarding the achievement of students with disabilities, the nature of their parents’ involvement, and their adult employment rates.40 One reason for this lack of information is that the diversity of students with disabilities makes it difficult to reach general conclusions about their access to opportunity.41 Recent efforts to gather data from large-scale assessments have been relatively unsuccessful because the scores for students with disabilities are not reported as a subgroup, making the average score results unreliable.42 Self-reported data of graduation rates, employment, and earnings of individuals with disabilities on census and other surveys is often unreliable due to confusion over the categories of disability provided, or reluctance to disclose the extent of a disability.43 Finally, most federal data for children with disabilities comes from data collected by each state; however, there is no uniform state-by-state data collection system, so the information varies based on quality, accuracy, and consistency.44 While the Department of Education’s Office of Special Education Programs has been working to produce more consistent data going forward, as of now there is still a lack of reliable data pertaining to individuals with disabilities.45 We recommend coordination between HUD and the Education Department regarding the fair housing implications of this data.

2. Concentrations of Poverty46

The concentration of poverty is defined as the percentage of all persons at or below the federal poverty line living in a geographically-defined neighborhood.47 The effects on individuals of living in neighborhoods of high poverty concentration are overwhelmingly adverse.48 Moving to low-poverty neighborhoods may improve the life chances of particularly young inhabitants through several distinct mechanisms: because of higher levels of neighborhood social organization that reduce the threats of violence and disorder; stronger institutional resources, such as higher quality schools, youth programs, and health services; more positive peer-group influences; and more effective parenting, due to parents living in safer, less stressful neighborhoods and enjoying better mental health or parents’ becoming employed.49

Historically, discriminatory housing policies have been strongly associated with the creation of high-poverty neighborhoods.50 Fair housing policies, therefore, must make affirmative efforts to dismantle concentrations of poverty at the neighborhood level.

Measuring Concentrations of Poverty

High-poverty neighborhoods are measured according to census data and are often defined as census tracts with poverty rates of 40 percent or higher.51 However, because that definition of concentration of poverty captures only the most extreme areas of poverty concentration within the United States, and does not convey the many adverse impacts on opportunity that living in an otherwise poor neighborhood might have on an individual, a more useful standard in the context of resource allocation decisions may be to define a geographical area as having a “high concentration of poverty” if ≥ 20% of its residents report income at 150% or less of the federal poverty level (“FPL”).52 Medium concentrations of poverty can be defined as 10%-19% of the residents reporting income at 150% of FPL, and low concentration of poverty neighborhoods should be defined as < 10% of the residents reporting income at 150% or less of the FPL.53

Other measures, such as the Neighborhood Sorting Index, may be used to analyze broader economic disparities.54 Because home values have been found to be highly correlative to greater opportunity outcomes, this indicator may also be a useful benchmark for determining neighborhood poverty.55 Data on home values, or housing cost, may be obtained from census data as well.

Additional Poverty Considerations

Income Adequacy. In addition to the federal poverty level, governmental evaluating entities should consider using definitions of “income adequacy” to determine what constitutes a high- opportunity neighborhood under the aforementioned rubrics. Income adequacy statistics take into account resources as compared to the market prices of basic necessities, as faced by the average consumer. For example, a measurement of income adequacy currently being developed by Wider Opportunities for Women: (1) places emphasis on the expenses a family must cover to make ends meet and not under-consume or consume inferior goods that affect health or safety; (2) takes into account pragmatic necessities including health care, transportation, and child and elder care; (3) uses market prices wherever possible; and (4) includes asset development savings targets for emergency savings and retirement, and possibly for education and homeownership.56

3. Racial Segregation

Research has long established that racial segregation adversely affects outcomes for minority groups, contributes to unequal opportunities and disparities, and robs residents of all races of the benefits of diverse social networks.57 One study of 204 metropolitan areas, for example, determined that a one standard deviation reduction in segregation (13 percent) would eliminate one-third of the gap between whites and blacks in most opportunity-related outcomes, where success was measured by high school graduation rates, jobs, earnings, and single-parent status.58

Additionally, racial segregation (i.e., the concentration of racial minorities) is a significant predictor of the share of subprime loans a neighborhood receives, even after controlling for the percentage of minorities within the metropolitan area as a whole, credit score, median home value, poverty, and education.59 By contrast, neither poverty nor unemployment is a statistically significant predictor of the percent of subprime loans.60 A 10% increase in black segregation, on average, is associated with a 1.4% increase in high-cost lending; and a 10% increase in Hispanic segregation, on average, is associated with a 0.6% increase in high-cost lending.61 Thus, in addition to the statutory mandate to avoid perpetuating or exacerbating segregation,62 research shows that residential integration is an important geographic indicator of opportunity.

Measuring Racial Segregation

To track changes in racial segregation in metropolitan areas, government bodies allocating federal funding should rely on the racial dissimilarity index63—the most widely used measure to capture the unevenness of a population’s distribution within a region.64 Because racial dissimilarity indices are derived from census data, they are readily accessible to all regional government bodies allocating federal funds.

The racial dissimilarity index indicates how unevenly two mutually exclusive groups (e.g., blacks and whites, or Latinos and whites) are distributed within a geographic area. It can be thought of as the percentage of either group that would have to move in order to achieve racial representation in each of the area’s census tracts, proportionate to the composition of the two groups in the broader region.

For example, if Latinos make up 20% of the population within a metro Core Base Statistical Area (“CBSA”), the Latino/white dissimilarity index tells us the percentage of Latinos or whites that would have to move in order to achieve the 20% level in all of the metro CBSA’s census tracts. Thus, a 65 score on the Latino/white dissimilarity index means that 65% of Latinos or whites would have to move in order to achieve a representative distribution of Latinos and whites throughout the region. The higher the dissimilarity index, the more the region is racially

segregated. Dissimilarity values of 60 or above are considered very high, while values of forty to fifty reflect moderate residential segregation.65 An evaluating agency can discern trends of particularly notable increases or decreases in residential segregation by examining changes in residential segregation within a decade. Changes in dissimilarity values exceeding ten points within a decade are considered significant in this context.66

4. Environmental Quality

Research demonstrates that, even after controlling for income, land use, and other variables typically used to explain disparate patterns of exposure, people of color and low-income communities bear a disproportionate share of the nation’s environmental and health hazards.67 Such disparities include: land use and facility siting; transport of hazardous and radioactive materials; public access to environmental services, planning, and decision-making; health assessments and community impacts; air quality and health risks; childhood lead poisoning; childhood asthma; pesticide poisoning; and occupational accidents and illnesses.68 These disparities thus disproportionately affect the life chances and opportunities of communities of color. According to research conducted by the United Church of Christ Justice & Witness Ministries, African Americans, Hispanics/Latinos, and Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders alike are disproportionately burdened by hazardous wastes in the U.S.69

Executive Order 12898: Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations,70 requires federal officials and those receiving federal financial assistance to incorporate into their respective cost-benefit analyses of federal projects a meaningful consideration of potential disproportionate adverse environmental and health impacts on minority and low-income populations. Embedded in this requirement is a set of considerations that need to be addressed by housing analysts as they evaluate the impact on fair housing of any proposed or ongoing housing projects.

Measuring Environmental Quality

Consistent with the suggestions of the What Works Collaborative,71 we recommend employing the following two measures of air and environmental quality: (1) the Toxic Release Inventory (“TRI”), a database that contains detailed information about the total amount of toxic waste released from industrial facilities; and (2) the National-Scale Air Toxics Assessment (“NATA”), which provides a modeled risk assessment at the tract level from exposure to 180 of the 187 CAA toxics based on TRI emissions, as well as nonpoint sources.72

The What Works Collaborative explains the method by which the TRI data may be matched to census tracts as follows:

[W]e used the approach adopted by Powell of creating a buffer of two miles around the address of a TRI emissions source. TRI has the advantage of including air, water, and land emissions. However, it ignores differences in the media into which emissions occur. For example, emissions into a river will disperse differently than those out of a smokestack. Still, it is difficult to construct a universal system of modeling emissions and a buffer is a decent first approximation.73

Additional Considerations

To simultaneously further the goals of neighborhood inclusivity and environmental sustainability, the What Works Collaborative suggests evaluating the walkability and transit accessibility of a particular neighborhood (i.e. focusing on how the neighborhood infrastructure allows households to avoid driving), in conjunction with other opportunity indicators.74 To

determine the walkability/transit accessibility of a neighborhood, the What Works Collaborative recommends considering: (1) the percentage of commuters commuting to work by walking or by public transit, derived from U.S. census data; and (2) the daily vehicle miles traveled per capita, derived from the Federal Highway Administration’s National Household Travel Survey.75 Due

to the disproportionate effect that environmental degradation has on disadvantaged populations, we support the analysis set forth by the What Works Collaborative. Thus, to the extent practicable, walkability and transit accessibility should be factored into a consideration of the impact on opportunity of housing or community development projects.

Although low-income communities and communities of color suffer from disproportionate rates of asthma, asthma data is difficult to consistently quantify. Some jurisdictions track hospitalizations, while others rely upon clinical admissions and results differ significantly based on which approach is taken. Data is further complicated by potential differences across metro areas in access to health care. Finally, because asthma incidence data are gathered at the health care facility, the addresses recorded are often incorrect. Accordingly, although we view asthma rates as an informative indicator of environmental opportunity, the available data sources limit its use on a uniform basis.

5. Medically Underserved Communities

Access to health care is an important determinant of one’s life chances. Minorities, however, are more likely to receive care in emergency rooms and lower-quality healthcare facilities.76 These racial disparities exist even controlling for insurance status and income.77 Thus, fair housing efforts must take into account the effect that housing and urban development projects have on increasing or decreasing the ability of community residents to access quality health care.

Measuring Medically Underserved Communities

National data on healthcare disparities is collected by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (“AHRQ”), a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.78 The AHRQ has developed mapping software that can be used with administrative data on individual hospital admissions to assess the number and cost of “preventable admissions” at the state or county level.79

To ensure that housing and urban development projects maximize community access to adequate, and not merely equal or proportionate (but inadequate) healthcare within a region, funding agencies should also refer to data provided by the Department of Health and Human

Services’ Health Resources and Services Administration (“HRSA”) on Medically Underserved Areas and Populations.80This data shows which areas within a region are medically underserved based on both the availability of primary care physicians and the health needs of communities— specifically, infant mortality rates in communities, as well as income and age of residents.81

6. Access to Jobs

Spatial access to skill-appropriate jobs has been used by a number of researchers as an indicator of access to opportunity.82 Due to shifts in labor demand from less-educated to more-educated portions of the workforce, well-paid, less-skilled jobs (i.e., in the manufacturing and other sectors) have significantly diminished, resulting in a skills mismatch that disadvantages less- skilled workers.83 Job growth in the central city has been in sectors that require higher skills, meaning that central-city jobs are no longer functionally accessible to less-educated city residents who might reside in the central-city (due to factors including racial segregation and poverty concentration), even if the jobs are physically accessible.84

Moreover, the physical distance from job-rich areas is exacerbated by the lack of automobile transportation.85 For example, one estimate found that inner-city residents with cars had access to fifty-nine times as many jobs as their neighbors without cars.86 Another recent study found that residential relocation and car ownership are the key factors in predicting the likelihood that welfare recipients will become employed.87 Transit-oriented development can link low-income residents with job centers.88 Because poor people are the least likely to have access to an automobile, transit-oriented development has been considered an approach to overcome barriers to opportunity faced by people in high-poverty residential areas.8990

Measuring Access to Jobs

To concretely evaluate the access to skill-appropriate jobs that a housing or urban development project will create, in accordance with analysis undertaken by the What Works Collaborative, government entities allocating federal funds for housing and urban development projects should consider:

- The absolute number of jobs requiring an associate’s level degree or below within a five- mile radius.

- The pattern of recent job growth within the area, to measure the total number of jobs as well as job trends.

- The ratio of total jobs requiring an associate’s degree or below within a five-mile radius91 to the total number of households earning under $50,000 per year within a five- mile radius, to control for likely competition for jobs.

This data can be obtained from the Census Zip Business Patterns, and may be filtered to focus on only those jobs requiring an associate’s degree education or below (those jobs most likely to be accessible to people served by HUD’s programs) by using Bureau of Labor Statistics (“BLS”) data showing the training required for each position.92

7. Crime and Security

Security from violent crime is an important opportunity indicator, particularly for women and girls.93 In the Moving to Opportunity (“MTO”) experiment, for example, girls whose families successfully moved to lower poverty communities experienced a substantial reduction in the negative mental health effects of “omnipresent and constant harassment; pervasive domestic violence; and a high risk of sexual assault,” and also experienced less “pressure to become sexually active at increasingly younger ages.”94 This diminished “female fear,” was linked to a reduction in the risks of pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases, and dropping out of school to care for children.95

However, in analyzing the effects of the MTO experiment on the psychological health of women and girls, evaluators of the experiment used low-poverty neighborhoods as a proxy for the prevalence of violent crime, instead of relying on actual crime rates.96 Thus, the MTO’s conclusions regarding the effects of the “female fear” present analytical difficulties. We recommend, instead, direct reliance on available crime statistics.

The use of crime rates as an indicator of opportunity is difficult, but not impossible, to quantify at local levels. The most commonly used measure of crime is the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report, which tracks both the violent crime rate and property crime rate.97 While the Uniform Crime Report data is national in scope, it is consistently available only at the political jurisdiction level and not at smaller levels, such as zip codes or census tracts.98In metropolitan areas with many small local governments, this shortcoming is not all that significant. In these cases, data supplied by the Uniform Crime Report should be relied upon by regional funding agencies in considering the proximity to crime of housing or urban development projects to be funded, and the resulting opportunity impact on the project’s residents or inhabitants. In some metropolitan areas, the failure of the Uniform Crime Report to differentiate between different parts of a political jurisdiction may produce data with limited relevance. However, many police departments do break out their Uniform Crime Report statistics at the tract, precinct, or zip code level.99 In such cases, those police department statistics on crime rates should be consulted in evaluating the opportunity impact of proposed and ongoing housing and urban development projects and activities. However, even the police departments that break out their Uniform Crime Report data at smaller geographic levels do not use a universal methodology.100

Conclusion

To best fulfill the duty to affirmatively further fair housing, governmental entities should balance the opportunity indicators discussed above, based on the totality of the circumstances, but weighted with greater priority to the initial indicators discussed.

The way in which indicators are used will necessarily depend in part on the program or activity in question. An important distinction exists, for example, between the siting of affordable housing—which should generally avoid low-opportunity neighborhoods—and neighborhood resources and improvements—which may be used to increase opportunities in otherwise low- opportunity communities.

The Opportunity Agenda welcomes the chance to discuss these recommendations further, in the context of revised AFFH rules and other agency decisionmaking.

Appendix A: Opportunity Indicators

Indicator

Measurement

Access to high-quality education

The percentage of students eligible for free lunch, math and reading test scores, and high school dropout rates

Concentration of poverty within a neighborhood

Federal Poverty Level (FPL) and measure of income adequacy within a neighborhood

Racial segregation within a census tract or neighborhood

Variation from the proportion of the non- white population regionally

Environmental quality within a neighborhood

Toxic Release Inventory and National- Scale Air Toxics Assessment

Access to healthcare

Data on health disparities from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, correlated to neighborhoods through their mapping software

Access to sustainable jobs

Data from the Census Zip Business Patterns and the Bureau of Labor Statistics

Crime rates

Data from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports and statistics from local police departments

Notes:

1. The opportunity indicators described herein are intended to deepen and clarify, not supplant, the existing site and neighborhood standards set forth in the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (“HUD’s”) existing regulations. 24 C.F.R. § 983.6 (2010).

2. See, e.g., JASON REECE ET AL., KIRWAN INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF RACE AND ETHNICITY, THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY, THE GEOGRAPHY OF OPPORTUNITY: BUILDING COMMUNITIES OF OPPORTUNITY IN MASSACHUSETTS 7 (2009).

3. Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C. §§ 3601 et seq. (2006).

4. 42 U.S.C. § 3608(e)(5) (2010).

5. N.A.A.C.P. v. Sec’y of Hous. and Urban Dev., 817 F.2d 149, 155 (1st Cir. 1987).

6. 42 U.S.C. § 3601 (2010).

7. Evans v. Lynn, 537 F.2d 571, 577 (1975) (citing 114 Cong. Rec. 9563 (statement of Rep. Celler)).

8. Trafficante v. Metro. Life Ins. Co., 409 U.S. 205, 211 (1972) (citing 114 Cong. Rec. 3422 (statement of Sen. Mondale)).

9. The Opportunity Agenda’s recommended reforms to HUD’s AFFH regulations.

10. For example, a number of studies have linked racial segregation to an increased likelihood of perpetrating and being victimized by violence and crime; voluminous literature has examined the “spatial mismatch” between predominantly African-American, older urban neighborhoods, and the employment opportunities in the suburbs and exurbs; and residents of poor, segregated neighborhoods experience poorer health outcomes because of increased exposure to the toxic substances that are disproportionately sited in their communities. See REECE ET AL., supra note 2, at 8.

11. See, e.g., THE OPPORTUNITY AGENDA, THE STATE OF OPPORTUNITY IN AMERICA: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY (2006) (evaluating the state of opportunity in the United States based on indicators related to: mobility, equality, voice, redemption, community, and security) [hereinafter STATE OF OPPORTUNITY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ]; see also THE OPPORTUNITY AGENDA, THE STATE OF OPPORTUNITY IN AMERICA, 2010 (2010) ( updating the data in the 2006 report).

12. The What Works Collaborative consists of researchers from the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program, Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, New York University’s Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy, and the Urban Institute’s Center for Metropolitan Housing and Communities, as well as other experts from practice, policy, and academia.

13. VICKI BEEN ET AL., BUILDING ENVIRONMENTALLY SUSTAINABLE COMMUNITIES: A FRAMEWORK FOR INCLUSIVITY (2010).

14. Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 493 (1954).

15. See, e.g., Shannon v. HUD, 436 F.2d 809 (3d Cir. 1970).

16. Id. at 822.

17. See, e.g., Brief for 553 Social Scientists as Amici Curiae Supporting Respondents, Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School Dist. No. 1, 551 U.S. 701 (2007)) (documented the effects of school integration on educational quality); Brief for Housing Scholars and Research & Advocacy Organizations as Amici Curiae Supporting Respondents 7, Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School Dist. No. 1, 551 U.S. 701 (2007). (“First, school segregation is practically inseparable from the many causes of housing segregation . . . residential segregation persists and is not simply the product of private free choice. Rather, the historical and contemporary practices of state and private actors, such as racial steering and mortgage lending discrimination, directly contribute to the persistent segregation of America’s neighborhoods. When a school district acquiesces to segregated residential patterns in drawing school attendance zones and setting student assignment policies it is in a very real sense affirmatively choosing segregation. Second, extensive social science research demonstrates that school integration programs support housing integration in both the short and long term. Parents are less likely to move when integration programs help to ensure racially integrated schools, and students who attend racially integrated schools are more likely to live in integrated neighborhoods as adults”).

18. KIRWAN INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF RACE AND ETHNICITY, K-12 DIVERSITY: STRATEGIES FOR DIVERSE & SUCCESSFUL SCHOOLS 4 (2007) (citing RICHARD D. KAHLENBERG, INTEGRATION BY INCOME, 193 AM. SCH. BD. J. 4, 51-52 (2006)).

19. Id. (citing HARRIS, D.N., EDUCATIONAL POLICY RESEARCH UNIT, ARIZONA STATE, ENDING THE BLAME GAME ON EDUCATIONAL INEQUALITY: A STUDY OF ‘HIGH FLYING’ SCHOOLS AND NCLB UNIVERSITY (2006).

20. Id. (citing Richard D. Kahlenberg, The Century Foundation, Can Separate Be Equal? (2004).

21. See, e.g., THE COALITION FOR A LIVABLE FUTURE, THE REGIONAL EQUITY ATLAS: METROPOLITAN PORTLAND’S GEOGRAPHY OF OPPORTUNITY 45 (2007).

22. See, e.g., National Center for Education Statistics, CCD 1999/2000 and 2002/03.

23. School Data Direct. (although School Data Direct is in the process of completing infrastructure upgrades, it is “targeting the middle of 2010 for a relaunch” of the website).

24. NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL, GOVERNANCE AND OPPORTUNITY IN METROPOLITAN AMERICA 67 (1999).

25. See Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity (unpublished report, on file with The Opportunity Agenda).

26. NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL, supra note 24, at 67.

27. See School Data Direct, supra note 23.

28. See, e.g., National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, Mathematics: The Nation’s Report Card (home).

29. See Linda Darling-Hammond, Educational Quality and Equality: What it Will Take to Leave No Child Behind, in ALL THINGS BEING EQUAL: INSTIGATING OPPORTUNITY IN AN INEQUITABLE TIME 49 (Brian D. Smedley & Alan Jenkins eds., 2007).

30. Id. at 50.

31. See Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity, supra note 25.

32. See Linda Darling-Hammond, supra note 29, at 49.

33. See, e.g., Oregon Department of Education, District Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) Report (2008-2009).

34. VICKI BEEN ET AL., supra note 13, at 48.

35. Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004, Pub. L. No. 108-446, § 601, 118 Stat. 2647, 2649 (2004).

36. Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act § 601.

37. See, e.g., Stacey Gordon, Making Sense of the Inclusion Debate under IDEA, 2006 BYU EDUC. & L.J. 189, 224 (2006).

38. Id.

39. AMERICAN YOUTH POLICY FORUM & CENTER ON EDUCATION POLICY, THE GOOD NEWS AND THE WORK AHEAD 10-11 (2002).

40. Id. at 10.

41. Id.

42. Id. at 11.

43. Id.

44. Id.

45. Id.

46. Government entities should not use poverty levels alone to determine the opportunity impact of a proposed or ongoing housing or urban development program. There is evidence that HUD’s focus on poverty level alone as its metric of opportunity in the Moving to Opportunity (“MTO”) experiment led to reconcentrations of voucher holders in outer-ring city and older suburban neighborhoods that were below the poverty threshold, but otherwise not high opportunity. BEEN ET AL., supra note 34, at 53; XAVIER DE SOUZA BRIGGS ET AL., MOVING TO OPPORTUNITY: THE STORY OF AN AMERICAN EXPERIMENT TO FIGHT GHETTO POVERTY 93, at 65 (2010) (“[B]asic compromises were made, in the outline of [the MTO] social experiment, that limited its reach in important ways: defining the fuzzy concept of an ‘opportunity’ neighborhood, for example, as a census tract with a low poverty rate rather than something more direct, such as an area with high-performing schools, job growth, or other traits”).

47. PAUL A. JARGOWSKY, ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF POLITICAL ECONOMY, UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS, SPRAWL, CONCENTRATION OF POVERTY, AND URBAN INEQUALITY 6 (2001).

48. See, e.g., NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL, supra note 24, at 54.

49. See BRIGGS ET AL., supra note 46, at 93 (internal citations omitted).

50. See JARGOWSKY, supra note 47, at 7 (“Poverty is concentrated in the United States for a number of different reasons. Historically, the single most important factor was racial residential segregation”).

51. See id., at 6.

52. See, e.g., JOAN M. PATTERSON ET AL., ASSOCIATIONS OF SMOKING PREVALENCE WITH INDIVIDUAL AND AREA LEVEL SOCIAL COHESION 58 J. EPIDEMIOL. COMM. HEALTH 692, 693 (2004).

53. In the many areas in which a local tax base funds government services, the tax base capacity, as determined by income level, of a particular neighborhood or community may bear a strong correlation to structures of opportunity. However, in many states, local property taxes have a lesser impact on funding local services than statewide taxes. Also, different structures of local government make this factor’s importance vary widely from state to state. Thus, the tax base capacity of a particular neighborhood may not be the strongest, or most easily quantifiable, indicator of opportunity within a particular geographic area. BEEN ET AL., supra note 34, at 53.

54. See BEEN ET AL., supra note 34, at 64.

55. See KIRWAN INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF RACE AND ETHNICITY, ongoing research (on file with author).

56. JOAN A. KURIANSKY & SHAWN MCMAHON, WIDER OPPORTUNITIES FOR WOMEN, A BETTER POVERTY MEASURE IS A STEP FORWARD, BUT ECONOMIC SECURITY IS THE TRUE GOAL (2010).

57. See, e.g., NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL, supra note 24, at 57-58.

58. See id. at 58; see also id. at 70.

59. GREGORY D. SQUIRES ET AL., SEGREGATION AND THE SUBPRIME LENDING CRISIS 1, 4 (2009).

60. Id. at 4.

61. Id. at 4-5.

62. The AFFH duty requires government actors to “remove the walls of discrimination which enclose minority groups,” Evans v. Lynn, 537 F.2d 571, 577 (1975) (citing 114 Cong. Rec. 9563 (statement of Rep. Celler)), and to foster “truly integrated and balanced living patterns.” Trafficante v. Metro. Life Ins. Co., 409 U.S. 205, 211 (1972) (citing 114 Cong. Rec. 3422 (statement of Sen. Mondale)).

63. BEEN ET AL., supra note 34, at 64; see also RUCKER C. JOHNSON, LONG-RUN IMPACTS OF SCHOOL DESEGREGATION AND SCHOOL QUALITY ON ADULT HEALTH 28 (2009), (using the racial dissimilarity index to measure racial segregation); ANTHONY DOWNS, NEW VISIONS FOR METROPOLITAN AMERICA 25 (Brookings Institution Press 1994) (similarly using the racial dissimilarity index to measure racial segregation).

64. But see Bruce Murphy, Study Explodes Myth of Area’s ‘Hypersegregation’: Researchers at UWM Rethink Racial Arithmetic of Major American Cities JSONLINE, Jan. 11, 2003 (presenting critiques of the racial dissimilarity index to measure of racial segregation).

65. JOHN LOGAN ET AL., LEWIS MUMFORD CTR., UNIV. AT ALBANY, ETHNIC DIVERSITY GROWS, NEIGHBORHOOD INTEGRATION LAGS BEHIND 2 (2001).

66. Id.

67. See, e.g., MANUEL PASTOR, JR., RACHEL MORELLO-FROSCH, & JAMES SADD, THE CENTER FOR JUSTICE, TOLERANCE & COMMUNITY, UNIV. OF CAL. SANTA CRUZ, STILL TOXIC AFTER ALL THESE YEARS…AIR QUALITY AND ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE IN THE BAY AREA (2007); JOINT CENTER FOR POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC STUDIES, BREATHING EASIER: COMMUNITY-BASED STRATEGIES TO PREVENT ASTHMA 2 (2004).

68. ROBERT D. BULLARD & GLENN S. JOHNSON, Just Transportation, in JUST TRANSPORTATION 10 (Robert D. Bullard & Glenn S. Johnson eds., 1997).

69. See ROBERT D. BULLARD ET AL., TOXIC WASTES AND RACE AT TWENTY: 1987-2007 xii (2007) (finding also that people of color comprise a majority in neighborhoods with commercial hazardous waste facilities, and much larger (more than two-thirds) majorities can be found in neighborhoods in which commercial hazardous waste facilities are clustered close together).

70. Exec. Order No. 12898, 59 Fed. Reg. 7629 (Feb. 11, 1994).

71. See BEEN ET AL., supra note 34, at 51-52.