I. Introduction

This memorandum discusses the contemporary relevance of residential integration to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s affirmative fair housing duties. Based on our review of legal jurisprudence, social science research, and expert opinion, we recommend a framework for incorporating integration considerations into housing and urban development decision-making.

In some ways, the topography of 21st century America reflects a thriving diversity in our country’s population: for example, as of the 2000 Census, Latinos comprised 12.5% of the population, up from 9% in 1990,1 and the number of Asian Americans had increased by 48% since 1990.2 The 2010 Census will no doubt show far greater diversity, including in formerly homogeneous areas. These shifting demographics raise the question of how best to further fair housing across all communities, especially where the implications of racial segregation may differ among different ethnic groups. Drawing on a thorough review of legal and social science research, as well as expert opinion, we conclude that racial integration remains a compelling directive of far-reaching relevance. Even as diversity is flourishing, patterns of segregation have held fast in cities throughout the nation. Those who inhabit them know that too often, segregated neighborhoods are not “separate but equal,” but rather are encumbered by the continuing effects of discrimination and isolation from opportunity. Even those who arrive in search of new beginnings – the many immigrants settling in communities across the country – frequently find their paths to opportunity impeded by the inequities that surround them.

Integration closes many of those gaps, while offering people of color the same benefits that accrue to all of us when our horizons are expanded: richer social networks to tap and opportunities to learn from those around us.

The continuing need to address residential segregation and its causes is a crucial aspect of the Fair Housing Act (FHA), and the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)’s mandate to affirmatively further fair housing (AFFH)3 should reflect that objective. While AFFH has a wide scope, it takes shape from the FHA’s core aims: “to provide, with constitutional limitations, for fair housing throughout the United States;”4 to “remove the walls of discrimination which enclose other minority groups;”5 and to foster “truly integrated and balanced living patterns.”6 In other words, the Fair Housing Act requires HUD proactively to promote non-discrimination, residential integration, and equal access to the benefits of housing – and these duties extend throughout the country, and to all ethnicities.

New immigrant communities and majority-minority jurisdictions add additional complexity, which we discuss below. But while demographic changes should be considered in assessing how to further fair housing, those changes do not remove or circumvent the integration mandate. As we discuss below, the FHA’s focus on segregation is of continuing and widespread relevance. Thus, while HUD funds may still be used to improve the choices and opportunity available to segregated communities, we believe that AFFH rules should include a strong presumption that decision-making and implementation will seek to foster residential integration and will not perpetuate or deepen existing segregation.

II. Legal Mandate

A. The Fair Housing Act and Integration

As noted above, integration is not a peripheral concern of the Fair Housing Act – rather, it constitutes one of the Act’s core directives. Since the FHA’s passage, courts have interpreted it to assert that integration is a focal fair housing mandate. In Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Insurance Co.,7 a cornerstone case of fair housing law, the Supreme Court held that, beyond advancing individuals’ freedom of choice, the FHA was intended to ensure the benefits of integration for “the whole community.” This principle was reinforced by the ruling in Gladstone, Realtors v. Bellwood, where the Court granted white plaintiffs standing on the basis that the “transformation of their neighborhood from an integrated to a predominantly Negro community is depriving them of ‘the social and professional benefits of living in an integrated society;’”8 see also Havens Realty Corp. v. Coleman.9 In Linmark Associates, Inc. v. Township of Willingboro, the Court again noted that through the FHA, Congress made “a strong national commitment to promote integrated housing.”10 The authors of the Act emphasized, for example, the troubling fact that “an overwhelming proportion of public housing . . . in the United States directly built, financed and supervised by the Federal Government — is racially segregated.”11 As with the FHA generally, the mandate to AFFH is grounded in these legislative concerns about segregation: Congress “enacted section 3608(e)(5) to cure the widespread problem of segregation in public housing.”3

The principle that integration is an essential aim of the Fair Housing Act has resonated throughout subsequent decisions delineating the FHA’s proper application, in contexts that include, but transcend, public housing. This line of cases includes: Otero v. New York City Housing Authority (finding that the New York City Housing Authority “is under an obligation to act affirmatively to achieve integration in housing. The source of that duty is both constitutional and statutory”), Park View Heights v. City of Black Jack (“[t]he primary objective of Title VIII is, as Vice-President Mondale said, when a Senator, to replace the ghettos ‘by truly integrated and balanced living patterns’…This objective is one that Congress considered to be of the highest priority and in order to achieve it, courts must construe the provisions of Title VIII broadly”), Metropolitan Housing Development Corp. v. Village of Arlington Heights (actions perpetuating segregation “will be considered invidious under the Fair Housing Act independently of the extent to which it produces a disparate effect on different racial groups”), Huntington Branch, NAACP v. Town of Huntington (courts should consider the “segregative effect of zoning ordinances,” as the perpetuation of segregation is a violation of the FHA), Altschuler v. HUD (through the AFFH provision, “Congress imposed on HUD a substantive obligation to promote racial and economic integration in administering the section 8 program”); as well as in Shannon v. HUD (holding that under its AFFH duty, HUD is required to make an “informed decision on the effects of site selection or type selection of housing on racial concentration,” and stating that “[i]ncrease or maintenance of racial concentration is prima facie likely to lead to urban blight and is thus prima facie at variance with the national housing policy”).13

While the Fair Housing Act’s passage was precipitated by concern over African American ghettos, numerous applications over the life of the statute have addressed barriers to the integration of other communities. Examples of this include: United States v. Secretary of HUD, 239 F.3d 211 (2d Cir. 2001); Davis v. New York City Housing Authority, 1992 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 19965 (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 30, 1992); NAACP v. City of Kyle, 2006 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 51226 (W.D. Tex. June 16, 2006); Hispanics United v. Village of Addison, 988 F. Supp. 1130 (N.D. Ill. 1997); Huntington Branch NAACP v. Town of Huntington, 844 F.2d 926, 937 (2d Cir. 1988); Anti-Discrimination Center of Metro New York, Inc. v. Westchester County, New York, 668 F. Supp. 2d 548, 564 (S.D.N.Y. 2009); United Farmworkers of Florida Housing Project, Inc. v. Delray Beach, 493 F.2d 799 (5th Cir. 1974); Jaimes v. Toledo Metropolitan Housing Authority, 715 F. Supp. 835 (N.D. Ohio 1989).14 In short, the courts have made clear that the integration mandate applies to all American communities, not just African Americans. Nor would it be legally appropriate, in any event, to interpret the Act differently as applied to different ethnicities.

B. Other HUD Regulations and Provisions Addressing Integration

Just as the concerns with segregation are clear in the FHA’s roots, they are also evident in its branches: a number of existing FHA regulations direct attention to the aim of furthering integration. These include:

- Affirmative Fair Housing Marketing Regulations, requiring participants in housing programs to reach out to ethnic groups to promote integration.15

Public housing authority program requirements regarding the location of new and renovated projects. This regulation prohibits the siting of new construction projects in:

- An area of minority concentration unless (A) sufficient, comparable opportunities exist for housing for minority families, in the income range to be served by the proposed project, outside areas of minority concentration, or (B) the project is necessary to meet overriding housing needs which cannot otherwise feasibly be met in that housing market area. An “overriding need” may not serve as the basis for determining that a site is acceptable if the only reason the need cannot otherwise feasibly be met is that discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, creed, sex, or national origin renders sites outside areas of minority concentration unavailable; or

- A racially mixed area if the project will cause a significant increase in the proportion of minority to non-minority residents in the area.16

- Nondiscrimination in Federally Funded Programs of HUD, prohibiting recipients from “subject[ing] a person to segregation or separate treatment in any matter related to his receipt of housing, accommodations, facilities, services, financial aid, or other benefits under the program or activity.”17

C. Integration and the AFFH Duty

While HUD has considerable discretion in determining the most effective means of AFFH, “that discretion must be exercised within the framework of the national policy against discrimination in federally assisted housing, and in favor of fair housing.”18 The duty to AFFH requires that HUD actively promote the FHA’s aims. It also requires that HUD responsibly administer its funds with an eye to their racial impact. Thus, HUD must ensure that the programs it funds promote fair housing goals. See, e.g., Gautreaux v. Romney (stemming the flow of HUD funding after determining that defendants perpetuated segregation); United States ex rel. Anti-Discrimination Center of Metro N.Y., Inc. v. Westchester County.19 HUD must also consider each project’s potential effect on racial segregation. Shannon v. HUD; see also, e.g., Project B.A.S.I.C. v. Kemp, stating that “this Court recognizes that desegregation is not the only goal of national housing policy. HUD also has an obligation to generally meet low-income housing needs. This, however, does not mean that HUD can avoid its affirmative duty under the Fair Housing Act” to consider the “effect of its actions on the racial and socioeconomic composition of the surrounding area.”20

Because Section 3608 imposes an affirmative obligation, it requires more than that the government “simply refrain from discriminating themselves or from purposely aiding discrimination by others” in addressing race.21 Rather, the Department must take active measures to achieve the FHA’s aims.22

Although the mandate to AFFH has lacked explicit parameters over much of its lifetime, it is clear that the aim of promoting racial integration lies at the provision’s heart. Thus, AFFH requires that “action must be taken to fulfill, as much as possible, the goal of open, integrated residential housing patterns and to prevent the increase of segregation[.]”23 HUD has been held to have an AFFH duty – despite the absence of any “specific actions or remedial plans” structured by §3608 – requiring “a commitment to desegregation. [HUD’s] failure to attain this standard can constitute an actionable statutorily violative practice.”24

Attempts to supplant the consideration of race in housing policy, if found to perpetuate segregation, will also be found to violate this AFFH obligation. See Langlois v. Abington Housing Authority, stating that “Section 8 residency preferences violate the affirmative furtherance principle when their institution would fortify predominantly white communities against minority entry;” United States ex rel . Anti-Discrimination Center of Metro New York, Inc. v. Westchester County, New York, 25 stating that “[t]he HUD Guide’s requirement that [funding] grantees analyze segregation [as part of their obligation to AFFH] is “firmly rooted in the statutory framework and caselaw….While the County was certainly not required to follow every specific suggestion or every recommendation in the HUD Guide, it cannot be completely wide of the mark regarding the suggestions relating to the central goal of the obligation to AFFH – to end housing discrimination and segregation – and still be considered compliant with its AFFH obligations,” and that using income as a proxy for race was not sufficient.26

HUD’s Fair Housing Planning Guide, as referenced in the Westchester27 case, also addresses the duty of racial integration. The Guide states that HUD “is committed to eliminating racial and ethnic segregation….Additionally, the Department will use all of its programmatic and enforcement tools to achieve this goal.” The Guide also instructs grantees regarding their obligations pertaining to integration, for example:

- Grantees must conduct analyses of impediments to fair housing, which must “describe the degree of segregation and restricted housing by race, ethnicity, disability status, and families with children; how segregation and restricted housing supply occurred; and relate this information by neighborhood and cost of housing.”28

- Public housing authorities are encouraged to use scattered site, low-density housing acquisition as means to deconcentrate racially impacted public housing.29

- States and local governments are encouraged to undertake regional FHP, with the aim of overcoming segregation.30

- In completing their Analyses of Impediments, states “can use available data… to gauge whether impediments to fair housing choice exist and whether there are State regulatory policies, practices, and procedures that encourage segregation by race, income, and/or disability….Upon completion of their AIs, States should take actions that are responsive to the identified impediments.”31

III. Integration in a Multi-Cultural America

As noted above, the legal integration mandate imbedded in the Fair Housing Act generally, and the AFFH duty in particular, applies across all racial and ethnic groups. Indeed, in the Supreme Court’s seminal Trafficante decision, it recognized the standing of white residents of a segregated white community based on “the loss of important benefits from inter-racial associations.”32 Courts have found that segregation of a variety of groups violates the Act.33

As we detail below, the desire for integrated communities is shared by contemporary communities of color. But it is worth noting here that the integration mandate has never been solely a matter of fulfilling the individual choices of African Americans or other minorities. Rather, the Fair Housing Act promotes integration in large part because of its benefits to society as a whole. Lack of enthusiasm, or even opposition at the individual level is not alone sufficient to justify governmental support of segregation.34 Thus, while individuals are free to self-segregate for any number of reasons, government may not enforce that choice,35 and HUD funds may certainly not be used to effectuate or perpetuate it.

That said, we detail below that there is strong evidence that different communities of color generally desire integrated neighborhoods, that past and present discrimination remain barriers to fulfilling that desire in the housing mandate, and that integrated living patterns benefit all groups in significant ways.

IV. Neighborhood Preferences and Causes of Segregation

A large body of research and experience shows that, while most minorities would prefer to live in integrated neighborhoods, they are denied this choice through a combination of segregative forces, including persistent discrimination, the legacy of historical barriers, white response to stereotypes, and narrow options for where they can affordably live.

While one study on Latino communities found that “it makes a difference whether immigrants or their descendants live in an ethnic neighborhood as a result of discrimination or due to their own choice or preference,”36 the meaningful ability to make such a choice is elusive for too many people. Thus, in a St. Louis study, even those residents who stated a preference for living in their West Side neighborhood (with a high concentration of immigrants) also noted a lack of affordable options elsewhere, and were discouraged by concerns about discrimination.37 Other research confirms that while blacks frequently remain segregated despite income, “as Latinos and Asians improve their socioeconomic class standing, their rates of segregation from whites decrease.”38

A body of opinion data indicates that most racial minorities would prefer to live in integrated neighborhoods, though some are hesitant to be pioneers in areas where they envision encounters with prejudice. For example, one study found that “African- Americans overwhelmingly prefer 50-50 areas, a density far too high for most whites –and that their preferences are driven not by racial solidarity or neutral ethnocentrism but by fears of white hostility. Moreover, almost all blacks are willing to move into largely white areas if there is a visible black presence. White preferences also play a key role, since [w]hites are reluctant to move into neighborhoods with more than a few African Americans.”3

Like blacks, both Latinos and Asian Americans have been found to prefer neighborhoods that are approximately 50% Latino or Asian and 50% white. Notably, only 17% of Asian Americans (in a study of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean Americans in Los Angeles) preferred the option of an all-Asian neighborhood when asked about integrating with whites.40 Opinion research has also found that “[o]nly a trivial percentage of blacks, Hispanics, and Asians express objection to living in a largely white neighborhood. The figure is below 10% for each of the minority groups.”41

Because people of color tend to seek greater levels of integration than do whites, even as minorities seek to leave behind their traditional neighborhoods in search of a more integrated life, white prejudice can turn this goal into a fleeting horizon. As minorities integrate communities, their increased population may reach a “tipping point” that causes whites to seek housing elsewhere. Such “‘[t]ipping’ can be seen clearly in cities from all regions of the country, both “sun-belt” and “rust-belt” and both the North and the South, and in cities with both large and small minority shares.”42 However, “tipping points are higher in cities with more tolerant whites, underscoring the role of white preferences in tipping and the dynamics of segregation.”43 While whites are most reluctant to live side- by-side with significant numbers of black neighbors, other races may trigger this as well: one poll found that one-sixth of whites would be upset if a “substantial number” of Chinese Americans moved into their neighborhood, 44 while low-income Asian Americans have been found more likely to cause white flight than either wealthier Asian Americans or Latinos.45 Thus, even where minorities seek to integrate, segregation may be re-imposed on them as whites retreat.

Segregation can become self-perpetuating in part due to negative stereotypes formed about non-white neighborhoods and their attendant lack of services.46 As one researcher stated, “[f]or blacks, Latinos, and Asians, economic and social advancement is associated with greater proximity and similarity to white Americans. For whites, integration – especially with blacks – brings the threat of a loss of relative status advantages. As a result, attitudes on an issue like racial residential integration are likely to have very different meanings to whites than to members of any of the minority groups, even comparatively affluent Asians.”47

Historically and today, people of color – including Latinos, Asian Americans, and Native Americans, as well as blacks – have been subject to discrimination limiting their options in housing. As with African Americans, segregation of other minority communities has been perpetuated by both governmental and private forces, including persistent discrimination in sales by white homeowners;48 disparities in the provision of banking and credit;49 and land use practices. Past practices often sculpt current realities, as in East L.A., where a history of restrictive covenants and other discrimination against Mexican Americans in Los Angeles has concentrated Latinos.50

Like other minorities, Asian Americans have grappled with the effects of both restrictive zoning and individual prejudice. For instance, some of the nation’s earliest zoning ordinances were enacted to contain the Chinese,51 and at least through the 1970s, “Asian families were reluctant to search for housing outside of Chinatown[s] because of racial discrimination… many whites refused to sell to Asians.”52 In Seattle, restrictive covenants barring the sale of land to Asian Americans were pervasive in the first half of the twentieth century, except for a few neighborhoods. As a result, “[p]eople of color had little chance of finding housing except in the central neighborhoods of Seattle.”53

Compared with whites, minorities of all races and ethnicities struggle to obtain fair credit to live where they wish.54 This problem is compounded by inaccurate information among minorities regarding the accessibility of housing. For instance, in a 2003 survey conducted by Fannie Mae, 78% of Spanish-speaking Latinos55 and 43% of blacks believed that loan applicants were required to have perfect a credit rating in order to qualify for a mortgage; 71% of Spanish-speaking Latinos and 51% of blacks believed that applicants with any debt, or who don’t always pay their bills on time, wouldn’t qualify for a mortgage.56

Discrimination in sales and rentals also continues, as minorities are steered toward homes in segregated neighborhoods. In 2003, an Urban Institute report submitted to HUD concluded that “significant discrimination against African American and Hispanic homeseekers still persists in both rental and sales markets of large metropolitan areas nationwide,” with discrimination against Hispanic renters unchanged since 1989.57 For instance, a fair housing audit in Fresno, California, found that Latino prospective renters encountered discrimination 77% of the time, while African American did so 74% of the time;58 in San Antonio, a rental audit yielded discrimination rates of 68% against African Americans and 52% against Latinos.59 A 2001 housing audit in Houston60 found that: 80% of African Americans, and 65% of Hispanics were treated differently when they sought to rent. The abuse of limited English speaking Latino immigrant communities is widespread in the rental and sale of housing. The immigrant Hispanic community is the fastest growing population in Houston. Abuse is manifested in many ways, such as contracts with exorbitant interest rates on mobile home sales, and the charging of rent based on the number of people in a unit. Recently many apartment complexes have been requiring Spanish speaking applicants to provide additional written information, more than normally asked of ‘Americans,’ in a divisive and potentially discriminatory practice.61

Asian Americans are often overlooked in analyses of housing discrimination, but many also encounter disparate treatment when seeking homes, for example in being informed of housing availability and in obtaining financing assistance.62 The 2003 Urban Institute study shows that Asian Americans face significant and consistent levels of discrimination in searching for housing in large metropolitan areas.63

Native Americans, too, find their housing choices shaped by racial steering. The Urban Institute found a “pattern of treatment that favors whites and ultimately limits the housing choices and increases the cost of housing search for American Indians. Discrimination against American Indian renters ranges from 25.7 percent in New Mexico to 33.3 percent in Minnesota, averaging 28.5 percent across all three states. These levels of discrimination are high compared to national estimates for African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians and Pacific Islanders. In all three states, American Indian renters were significantly more likely to be denied information about available housing units than comparable whites.”64 Although approximately two-thirds of Native Americans lives outside of reservations or designated tribal areas,65 racial steering still limits individuals’ living choices.

While anti-‐discrimination enforcement, by HUD and others, ensures that such practices do not reach the pervasive levels of the past, discrimination still contributes to the channeling of minorities into segregated neighborhoods.

V. Benefits of Integration and Harms of Segregation

The harms of segregation and benefits of integration have been well-documented,66 and touch on all ethnic groups. While Americans increasingly inhabit a multi-ethnic society, opportunities continue to be distributed along racial lines. As a result of continuing inequities, segregation and poverty travel together; race makes itself felt not only in the socioeconomic disparities between individuals, but also though the compound effects of concentrated poverty. Segregation also concentrates other effects of discrimination, such as the disproportionate lack of financial and other services; and perpetuates negative stereotypes, sapping confidence and undermining inter-ethnic cooperation. These harms are not limited to black communities: they also resonate in Latino and Asian American neighborhoods, including those of recent immigrants.

While integration is vital to ameliorating the socioeconomic injustices that follow racial boundaries, it is also an important end for the American community at large. As the Supreme Court held in Gladstone, we all have an interest in “the social and professional benefits of living in an integrated society.”67 The pursuit of residential integration provides richer social interactions, enables a wider base of professional and other contributions to draw upon, and mirrors that of educational settings in that it endeavors to create opportunities to learn from each other.68 Like minorities, whites stand to gain from policies that advance integration. Currently, whites are distinguished as America’s most segregated ethnic group: “the average white person in US cities and suburbs lives in a neighborhood that is overwhelmingly white (about 84%) and thus offers little exposure to other racial or ethnic groups.”69

A. Concentration of poverty and other financial inequities

Blacks, Latinos, Native Americans, and many Asian nationalities70 on average earn less than whites;71 but it is the distribution of poverty, not the gap between individuals alone, that has a particularly harmful effect on segregated communities. Minorities are much more likely to live in areas of concentrated poverty, meaning that poverty’s social effects reverberate and are amplified throughout their communities.72 Thus, poor blacks and Native Americans were three times more likely than poor whites to live in extreme- poverty areas. Poor Latinos and Asian Americans were both roughly twice as likely.73

Even when income disparities don’t loom, segregated neighborhoods still suffer more sharply from the effects of poverty because of its distribution. For example, in Riverside- San Bernardino in 2000, “the median household incomes of blacks and whites were $42,600 and $46,600, the smallest black-white difference in any of the 50 metros with the largest black populations. Yet the average black home in Riverside was located in a neighborhood with a poverty rate (18 percent) that exceeded the rate for the corresponding white neighborhood by 42 percent. The former also had 24 percent more unemployment, 24 percent fewer college-educated residents, and 12 percent fewer home- owners. The median household income for Hispanics, $40,700, also was fairly close to the white median. But the neighborhood poverty rate for the typical Hispanic household exceeded the “white” neighborhood rate by 45 percent. And the Hispanic neighborhood had 26 percent more unemployment, 35 percent fewer college graduates, and 12 percent fewer homeowners.”74 Segregation combines with structural inequalities to magnify socioeconomic deficits for minorities.

Differences in income derive partially from a spacial mismatch between job sites and minority residences, in part due to lack of business investment in minority neighborhoods. Where blacks, Latinos, and Asian Americans were most segregated from whites residentially, they also experienced the greatest mismatches between their residences and available jobs.75 Additionally, the very fact of segregation limits the job and other opportunities available to minorities by constricting their social networks.76

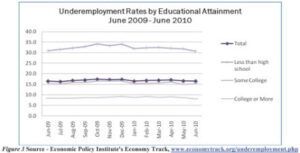

As with other minorities, the segregation of Asian Americans can concentrate poverty and other socioeconomic detriments. “Model minority” stereotypes mask the reality that Asian Americans are widely diverse, with average levels of income and educational attainment varying significantly among nationalities.77 53.3% of Cambodians, 59.9% of Hmong, 49.6% of Lao, and 38.1% of Vietnamese over the age of 25 have less than a high school education, and while Asian Americans are more likely than whites to have incomes over $75,000, they are also more likely to have incomes under $25,000.78 As with blacks and Latinos, high poverty rates among many Asian American sub-groups mean that communities where those ethnicities cluster are characterized by financial deprivation and its attendant effects.

Segregation also creates barriers to building wealth, as financial discrimination in lending and other services further inflicts communities with high concentrations of minorities. Banks and businesses are less likely to invest in neighborhoods with high concentrations of minorities; such neighborhoods continue to be undercapitalized in comparison to economically comparable white neighborhoods.79 Even controlling for socioeconomic characteristics, minority neighborhoods have higher concentrations of payday loans.80

Racial bias in finance also affects individual borrowers living in segregated communities, as reflected in the distribution of subprime loans: borrowers residing in zip codes whose population is at least 50% minority are 35% more likely to receive loans with “prepayment penalties” than financially similar borrowers in zip codes where minorities are less than 10% of the population; high-income African Americans in predominantly black neighborhoods are three times more likely to receive a subprime purchase loan than low-income white borrowers in predominantly white neighborhoods.81

These disparities are not limited to blacks: blacks, Native Americans, Asian Americans, and Latinos pay higher rates for home mortgage loans than whites do, even controlling for factors such as income and credit history.82 Subprime foreclosures are concentrated in predominantly minority – particularly black, Latino, and Native American – neighborhoods.83 For example, in one Arizona county, while Latino borrowers held 11.9% of home loans, they were 34.7% of the foreclosures. As a direct result of each foreclosure, the value of surrounding homes also falls.84 Because of such disparities, minority neighborhoods “will be disproportionately likely to suffer vacant and abandoned properties, as well as increases in crime and decreases in property values, which have been found to result from foreclosure activity.”85

B. Other effects of discrimination on segregated communities

In addition to financial disparities and their attendant effects, high-minority areas suffer from the concentrated effects of myriad forms of discrimination. Such areas are disproportionately exploited in the siting of environmental hazards, even controlling for income levels.86 Minorities are also more likely to be stranded without adequate local services, as municipal incorporation (which generally bundles and delivers those services) often bypasses segregated communities.87 See, e.g., Committee Concerning Community Improvement, et al., v. City of Modesto, County of Stanislaus, Stanislaus County Sheriff (plaintiffs with FHA claim were residents of predominantly-Latino neighborhoods, which were unincorporated “islands” surrounded by Modesto; and which lacked basic infrastructure such as sewer lines, sidewalks, and storm drains);88Lopez v. City of Dallas, Texas89 (alleging that Dallas provided inferior municipal services to residents of Cadillac Heights); Kennedy v. City of Zanesville (alleging decades-long discriminatory government policy of refusing to provide clean water to neighborhood due to its racial makeup). 90

Segregation can exert a particularly harmful influence on children: studies have shown that minority students who attend diverse schools have higher high school and college graduation rates, as well as being aided by the ability to “connect to social and labor networks that lead to higher earning potential as adults.”91 Integrated schools also confer important benefits in the form of lessons about the value of intercultural cooperation.92 The direct link between integrated schools and integrated communities is clear.93 Yet while segregation in schools mirrors residential patterns, it can be even more sharply felt; due to demographic trends, segregation rates among children can be even higher than among the general population.94 School quality is directly impacted by the financial costs of segregation noted above: as incomes and property values are lower, so is the tax base from which schools (and other services) draw.

C. Residential Distance and the Perpetuation of Stereotypes

While segregation is measured by physical distances, it also reflects social distances that hold members of different races permanently at bay. By facilitating exposure to other cultures and contact among individuals, racial integration can dispel harmful stereotypes and help to dismantle the discriminatory cycles that perpetuate racial distrust. Numerous studies demonstrate that meaningful contact between members of different races significantly reduces prejudice among racial groups.95 For instance, in the educational setting, studies of voluntary integration plans demonstrate that students in racially diverse educational environments feel comfortable with, and prepared to work and interact with, members of other races.96

VI. Relevance of Integration on Grounds Other Than Race

Just as racial integration is a necessary element of the AFFH duty, integration on other covered grounds is also important. In addition to considering race and ethnicity, AFFH should encompass the fair housing rights of those with disabilities, as well those of various national origins, religions, and familial status, to participate equally in society without the constraints of segregation.

The integration obligation regarding the disabled is reflected in existing law, including Executive Order 13217, which provides that the federal government should ensure placement of individuals with disabilities, whenever possible, in community settings rather than institutionalized environments; HUD’s regulations on discriminatory housing practices, which prohibit “assigning any person to a particular section of a community, neighborhood or development, or to a particular floor of a building, because of race, color, religion, sex, handicap, familial status, or national origin;”97 and criteria used by HUD in the competitive selection process for awarding funds for the development of housing and supportive services for people with disabilities, which are intended to avoid high concentrations of people with disabilities in one project, or on one site, and that reward siting features that are shown to “facilitate [residents’] integration into the surrounding community and promote their ability to live as independently as possible.”98

Furthermore, housing integration efforts amongst people with disabilities has been shown to yield positive effects. During the 1970s, a wave of legal decisions assisted in shifting housing priorities from institutionalization to community based assistance.99 In addition to increasing scrutiny of rights violations occurring in these institutions, studies testing alternatives to mental health treatment demonstrated positive benefits on employment, self esteem and social groups for patients placed in community placement programs.100

Currently, discourse pertaining to people with disabilities emphasizes the goal of “normalization,” which provides for the integration of people with disabilities with “patterns of life and conditions of everyday living which are as close as possible to the regular circumstances and way of life of society.”101 These objectives seek to address both the integrative potential and therapeutic benefits that residential integration of people with disabilities provides.102

The residential integration of persons of various religions similarly offers both inter- and intrapersonal benefits to communities involved. Exposure to groups from different backgrounds provides a forum for informal learning,103 while emphasis on acknowledging and valuing diversity allows community members to feel comfortable within the broader society.104 A recent British study on faith-based housing associations demonstrated greater cooperation among different faith-based groups, leading to “greater community cohesion,” through increasing “dialogue” and “understanding” between the numerous religious communities.105 Additional studies also illustrate the broad impact of religious diversity on group identification and their contributions to “mainstream culture.”106

VII. Fair Housing and Immigrant Communities

While is clear that desegregation is a crucial consideration in effectively furthering fair housing, it is also important to be sensitive to the varying needs of different communities. This is clear, for instance, in the context of relatively recent immigrants, who are characterized by abundant variation in socioeconomic status and other attributes. As noted in the section on integration above, average levels of income and educational attainment vary significantly among nationalities, and the character of ethnic “enclaves” can vary broadly as well.

Such neighborhoods, though they are frequently segregated by race and ethnicity, can sometimes be an important stepping stone in immigrants’ path to opportunity. As one scholar has noted, “enclave neighborhoods are especially important in facilitating the socioeconomic incorporation of immigrants faced with language and skill barriers. The concentration of linguistically isolated and poor Asian Pacific Americans affirms this central function of enclave neighborhoods. Moreover, it is consistent with the demography of enclave neighborhoods that a larger share of the foreign-born reside in concentrated neighborhoods relative to other neighborhoods types, with only a small share of homeownership indicating a concentration of rental housing and a denser environment.”107

While recognizing the transitional benefits that these neighborhoods provide, however, it is important to recognize that their segregated character takes a toll on the housing and other opportunities of their residents. Thus, while many Asian Americans tend to be well off relative to other Americans, in New York, Los Angeles, Oakland, and San Francisco, urban Chinatowns “have high rates of poverty and linguistic isolation as well as minimal levels of APA homeownership;” many other enclaves, of both urban and suburban location and of various ethnicities, have similar features.108 This pattern is not all-encompassing: other enclaves, for instance, have more recently been settled by middle- and upper class immigrants, and may be “suburban settings…which are quite affluent indicated by high levels of median household income and APA homeownership.”109 However, in general it has been found that “for blacks, Hispanics, and Asians living in metropolitan areas with a high percentage of foreign-born residents (gateway communities) higher education and, to a lesser extent, higher income are associated with higher rates of residential integration with whites.”110

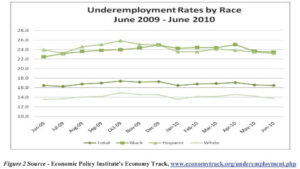

As with native-born minority communities, segregation of immigrants can concentrate poverty and its effects. The Pew Center has documented sharp declines in non-citizens’ income over the past several years, as well as disproportionate unemployment among Latino immigrants.111 Immigrant communities have the added burden of linguistic isolation. For example, among Asian Americans, based on the 2000 Census, 46% of Vietnamese households are linguistically isolated; 41% of Korean households are linguistically isolated; 35.3% of Chinese households are linguistically isolated; 34.8% of Hmong households are linguistically isolated; 11.1% of Filipino households; and 10.8% of Asian Indian households are linguistically isolated. By comparison, only 4.1% of all U.S. households are linguistically isolated.112 24% of Asian schoolchildren are ELLs, as are 31% of Latinos.113

While some minorities – especially recent immigrants – do benefit in some ways from living together in close-knit enclaves, research finds there are both “profits” and “deficits” attached to such communities.114 Thus, while immigrants in these neighborhoods enjoy the accessibility of same-language services and ready access to social networks, they are also likely to suffer from poor educational opportunities, lower housing values (partly attributable to designation as an “ethnic neighborhood”), and low- quality, dilapidated infrastructure.115 While some services are more readily accessible, others are lacking. For instance, “[t]he severe underrepresentation of Latinos in fields such as law, the health professions, and teaching has led to a deepening crisis – namely, an astonishing scarcity of educators, legal service providers, and health care providers with the linguistic resources and cultural sensitivity to serve the growing Latino community.”116 Even as “ethnic enclaves offer assistance to new arrivals, from help in finding housing to securing a job and child care, obtaining familiar food, and celebrating religions and cultural traditions….ethnic enclaves can also be constraining, in that they limit contact with English speakers, who tend to have higher incomes, greater educational attainment, and valuable social networks.”117

One influential study on the dynamics of immigrant assimilation found that “[w]hile children from high socioeconomic status immigrant families in suburbs may likely achieve similar levels of success to their [white] native peers, immigrant families in inner cities are likely to be attended by serious difficulties facing the children of their neighboring native minorities…Ethnic enclaves in communities with strong socio- economic resources may provide support to help assimilation into the middle class. In socioeconomically unprivileged communities, however, assimilation may mean downward social mobility (e.g., high school dropouts, youth delinquency, gang affiliation) because those communities lack the resources necessary to help poor families to steer children from local peer pressures and oppositional cultures.”118

Such barriers to achievement often are reflected in local schools. “New immigrant families tend to reside, at least initially, in lower-cost central city and older ring suburban neighborhoods. This trend places newly arriving school-age children – especially Latino and Asian American students – in schools already troubled by declining resources.”119 As discussed above, residential segregation, because it leads to school segregation, can burden immigrant children with linguistic as well as spacial isolation. Language differences also deter parental participation in schools with heavy immigrant enrollment.120

Additionally, children of immigrants gain from integration with peers who are native speakers of English. As a group of experts explained in a recent Supreme Court brief, “integration benefits advance the interests of [English language learners, i.e. ELLs] as well, who experience segregation particularly acutely, and who experience particular challenges and harms as a result of their racial and linguistic isolation in disadvantaged schools. Despite [the Supreme] Court’s holding in Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974) that ELL students have a right to a “meaningful and effective” education, a large proportion of ELLs are poorly-served in schools characterized by ethnic and linguistic isolation and concentrated poverty. Because ELLs are so likely to attend school with other ELLs and to live in racially and linguistically isolated neighborhoods, they have few contexts in which to interact with English-proficient peers. Integrated schools can create meaningful opportunities for this peer interaction.”121

Just as it is important to note that immigrant enclaves carry benefits as well as deficits for their inhabitants, it is also important to note that the benefits are not inextricably tied to a high degree of segregation. Among immigrants, degrees of integration fall along a varied spectrum: for instance, among Asian Americans in Los Angeles, Filipinos were most likely to live in racially mixed communities; Vietnamese, to live in majority-white communities; and Koreans, to live in either racially-mixed or majority-white communities.122 Those of Vietnamese and Filipino ethnicity were approximately as likely to live in majority-Latino neighborhoods as they were to live in neighborhoods where the majority were their own ethnicity; and all three groups were relatively unlikely to live in neighborhoods where the majority were Asian Americans of another ethnicity.123 Additionally, the composition of ethnic “enclaves” takes a multiplicity of forms and meanings. Surveys taken in Los Angeles found that “about 40% of Chinese American respondents identified Chinatown as a ‘most’ or a ‘very’ important center of business, cultural and social activity in their daily lives, while almost two-thirds identified the San Gabriel Valley similarly. Well over 80% of Korean- and Vietnamese- Americans either identified Koreatown or Little Saigon as a “very” or “most” important center of life or in fact lived in those neighborhoods. As with the tendency to form close friendships [with members of the same ethnicity, as also captured by this poll], this tendency is notably more visible among the newer immigrant groups.”124 Yet, as noted above, the majority of those respondents live in integrated neighborhoods, and even neighborhoods that may leap to mind as marquis ethnic settings in fact reflect an integrated reality – for example, Los Angeles’ commercially vibrant Koreatown is predominantly Latino and only approximately 20% Korean.125

In some cases, as patterns of immigrant settlement (particularly among the middle- and upper-class) shift to the suburbs, “traditional enclaves . . . have evolved into a symbolic community serving as cultural centers” while the majority of the population that patronizes them lives elsewhere.126 The symbolic value of such neighborhoods to some Asian-Americans is illustrated by the efforts of California Filipinos to designate official Filipino Towns that could serve as “visible spatial communities,” after urban renewal and gentrification drove residents from sections of cities including San Francisco, Honolulu and Seattle.127 While illustrating the importance of ethnic communities, these recent endeavors are the result not of segregative settlement patterns, but rather of concerted community efforts and of hard-won entrepreneurial and political capital – in other words, enabled by the same sort of access to resources and networks that heightened segregation is likely to impede.

VIII. Proposed Standards and Criteria for Promoting Integration Across Geographic, Racial, and Other Community Characteristics

HUD’s mandate to AFFH requires that fair housing policy navigate the range of communities across the United States, complete with their myriad demographic features and competing priorities. While applications in the field may vary, AFFH’s foundational objectives – to promote non-discrimination, residential integration, and equal access to the benefits of housing – stand as universal directives. As we have discussed above, segregated communities most often arise because of direct or indirect discrimination and restricted choice. And they most often have a detrimental effect on majority and minority group members alike, across America’s various racial and ethnic communities. This is not to say that members of minority groups may never rationally choose a neighborhood in which their group predominates, or that no benefits can ever flow from that choice. Rather, the law is clear that neither the Federal government nor its grantees may further segregation or ignore achievable integration in the implementation of their programs and activities.

Accordingly, we believe that AFFH rules should include a strong presumption that decision-making and implementation will seek to foster residential integration and will not perpetuate or deepen existing segregation. This presumption should apply, moreover, across all of the jurisdictions receiving HUD support, and across racial, ethnic, and other covered groups and characteristics. Guidelines should make clear that activities which perpetuate or deepen segregation, or that avoid integrative options, will constitute “red flags” warranting further scrutiny and the expectation that funding will be denied, terminated, or rescinded.

At the same time, however, we believe that the presumption against non-integrative uses could conceivably be rebutted in certain narrow, clearly defined circumstances. If, and only if, a proposed or existing use of Federal funds will both (a) substantially increase choice across identity groups; and (b) substantially increase access to other types of opportunity, we believe that a non-integrative approach might be considered under the following circumstances:

- Where the fund recipient is a municipal jurisdiction that is overwhelmingly racially homogenous, the use of funds would substantially increase choice and opportunity for residents of low-opportunity neighborhoods, and no metropolitan or regional approaches are possible. In other words, where there is “no one to integrate with,” and resources would achieve other important fair housing goals. For example, Community Development Block Grants could be used for the rehabilitation of structures and the construction of public facilities in such areas.

- Where funds would increase choice and access to opportunity, would support the transition of new immigrants into American and local society, and would simultaneously facilitate the longer-term integration of community members into the broader jurisdiction or region. That is, jurisdictions may be able to use HUD assistance to maximize transitional assistance to new immigrants in existing immigrant “launch pad” communities.

- Where funds are unlikely to have either a positive or negative impact on integration, but will increase choice and opportunity in low-opportunity segregated neighborhoods. This circumstance is most likely to arise when funds are used for purposed other than affordable housing creation. Accordingly, these principles do not prevent HUD from investing in the improvement of majority- minority neighborhoods, for instance through improved infrastructure or connection to municipal services. Examples of programs through which such funds could be allocated include Community Development Block Grants and the Initiative for Renewal Communities and Urban Empowerment Zones, as well the Public Housing Capital Fund and (working in tandem with the Department of Energy) the Weatherization program.

The most difficult question, in our view, arises when a majority-white jurisdiction seeks to create or expand the availability of affordable housing within a segregated, low- opportunity neighborhood, based in part on expressed demand from that community’s residents – in other words, where minority residents’ expressed “choice” is for expanded housing in their existing, segregated neighborhood.

In our view, HUD funds should rarely if ever be used for this purpose. First, as noted, research shows that people of color typically prefer integration over segregation, especially under low-opportunity conditions. Second, the Fair Housing Act and AFFH obligations do not exist to facilitate minority preference but, rather, to ensure non- discrimination, integration, and access to opportunity – conditions that do not exist in the above scenarios. And third, experience shows that there will frequently be integrative alternatives available to the jurisdictions, such as siting affordable housing at the juncture of existing majority and minority neighborhoods, and in high opportunity locations.

Again, this conclusion does not prevent the use of HUD funds to improve the choices and opportunity available to segregated communities. Rather, it prevents the use of these funds to perpetuate or deepen residential segregation.

Finally, it is worth stating that access to HUD programs, activities, and assistance is a limited resource that must be allocated strategically by the Department and consistent with applicable statutory priorities and parameters. Avoiding applications that would undermine the national interest in integrated communities is an important part of that interest.

IX. The Practical Importance of Attending to Racial Dynamics

Experience shows that failing to consider racial dynamics, or using socioeconomic status as a proxy for race, will frustrate the achievement of the Department’s mission and mandate. Programs implemented in the past have often been missed opportunities for furthering integration, as insufficient consideration was given to racial dynamics. For instance, the Massachusetts Low and Moderate Income Housing Act (nicknamed the Anti-Snob Zoning Law) successfully facilitated the construction of subsidized housing throughout the state by allowing developers to bypass local zoning practices. However, the law has been criticized for benefiting mostly whites and for having “exacerbated racial segregation:” only one-third of the housing was for families, while the remainder was occupied by elderly (white) local residents.128

In the Mount Laurel Cases, the New Jersey Supreme Court struck down a local exclusionary zoning ordinances and required towns in the state to construct their “fair share” of affordable housing.129 In the wake of the remedial phase, however, it was found that minorities were underrepresented in the new inclusionary developments, despite heavy demand. Although desegregation had been a stated goal of the program, it was an unrealized one; segregation in New Jersey has since increased.130The resulting construction chiefly “helped low-income suburbanites retain residency in their areas rather than open up new opportunities for urban people of color.”131 According to opportunity expert John Powell, New Jersey faltered by applying “the false premise that race issues can be reduced to poverty issues,” and mistakenly left the issue of residential segregation to the local authorities’ discretion.132

In contrast, Montgomery County’s inclusionary zoning law, requiring new large developments to provide affordable units, has primarily benefited minorities; the Maryland county is now regarded as “one of the nation’s most racially and economically integrated communities.” Although the program does not apply explicit racial criteria, it includes specific mechanisms to achieve integration. It succeeds by giving the local housing authority (which maintains a long waiting list of people of color) control over a large portion of the units; and by distributing the units by a widely-advertised lottery (thus avoiding the discriminatory tendencies of the housing market). In other cities, similar ordinances lacking such features have failed to ease segregation.133

Especially as we become an increasingly diverse society, it is important that HUD help integrated neighborhoods to flourish. Multifaceted approaches to sustaining integration should be an important consideration in furthering fair housing. An examination of cities in various regions of the United States found that stable, diverse communities typically exhibit common features, including the co-existence of multiple ethnic groups, attractive infrastructure (such as high-quality housing stock), the availability of affordable housing, and relationships with banks and real estate agents. Governmental forces can help nurture such communities, by ensuring access to financial support (such as loans for housing maintenance and business incubation), fostering diversity through anti- discrimination laws, public education measures, and other means.134 Additionally, efforts to integrate individuals should be sensitive to their needs. In terms of countering prejudice, integration has the strongest impact when it results in “meaningful contact,” that is, when “members of different groups have equal status, common goals, are in a cooperative or interdependent setting, and have support from authorities.”135 To the extent possible, HUD and its grantees should coordinate their work with that of other agencies 136 to facilitate integration: for example, with language instruction programs; inclusive vocational training and apprenticeship tracks; and by providing funding to inter-‐ethnic community organizations.

X. Additional Considerations

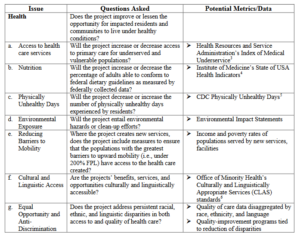

HUD’s AFFH imperative to further integration touches upon all HUD-funded activities, as well as all “programs and activities relating to housing and urban development” that are administered within the purview of Federal regulatory or supervisory authority.137 In addition to the principles described in Section VIII, a number of complimentary strategies can be used to further integration. For instance:

Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher Programs:

HUD should take steps to expand housing options for Section 8 voucher recipients, the majority of whom are minorities,138 in order to further integration by expanding individual choices. Portability requirements among public housing authorities are frequently discretionary, and can raise hurdles for families who seek to move between jurisdictions (even though PHAs are required not to discourage families from making use of portability).139 Procedural obstacles to movement among PHA jurisdictions should be analyzed and addressed.140 For example, among other strategies, HUD should consider implementing regionally-based administration of Section 8 programs in the place of PHA-run programs, to facilitate mobility and counteract NIMBYism among individual PHA jurisdictions.141 Currently, the Section 8 Guidebook142 states that PHAs must provide families with information about available neighborhoods within the PHA’s jurisdiction, as well as about the advantages of moving to a low-poverty neighborhood, but does not require that PHAs provide an in-depth counseling program. Counseling, which has been shown to have measurable benefits, should be provided for both voucher landlords and recipients.143 HUD should also further integration in Section 8 voucher use by affirmative marketing of rental openings in areas of low minority concentration.

HOME Investment Partnerships Program:

Siting of HUD-funded housing should require a comprehensive Opportunity Impact Statement,144 which would include an explicit inquiry into the proposed project’s effect on racial and socioeconomic integration, choice, and access to opportunity. In determining whether a project is to be located in an area of minority concentration, both local and regional data should be considered. Public input should be solicited from potentially impacted communities, including individuals of limited English proficiency. In addition to furthering fair housing, efforts to include Asian Americans in these planning processes should comport with President Obama’s Executive Order restoring the White House Advisory Commission and Interagency Working Group to address issues concerning the Asian American and Pacific Islander community, requiring HUD to, among other things, “identify Federal programs in which AAPIs may be underserved and improve the quality of life for AAPIs through increased participation in these programs…[to] increase public-sector, private-sector, and community involvement in improving the health, environment, opportunity, and well-being of AAPIs; [and to] foster evidence-based research, data-collection, and analysis on AAPI populations and subpopulations, including research and data on public health, environment, education, housing, employment, and other economic indicators of AAPI community well being.”145

Community Development Block Grants:

As with other HUD-funded projects, the CDBG allocation process should encompass an Opportunity Impact Statement146 that explicitly addresses integration.147 HUD should ensure that grantees comply with requirements that they enact plans for diverse citizen participation in planning decisions, as indicated in the Fair Housing Guidebook.148 These plans should encompass outreach to immigrant groups, including people of low English proficiency. As informed by this citizen participation and by robust data collection measures, CDBG spending should redress the effects of discrimination and segregation by ameliorating inequities in service provision, infrastructure, and other programs. HUD should also ensure that CDBG recipients comply with fair housing and nondiscrimination laws, as specified in its Toolkit on Crosscutting Issues for CDBG.149 Neighborhood Stabilization Program funds (a component of CDBG) should be used to expand opportunities in integrated areas.

Increased Outreach and Anti-Discrimination Enforcement for Ethnic Groups:

To promote greater choice in housing, fair housing enforcement funds should be increased and targeted to counter discrimination against all minorities. While blacks suffer the highest reported rates of housing discrimination, enforcement efforts frequently fail to reach other groups. For example, “[t]he inadequacy of efforts to engage Latino communities in the enforcement process and poor federal funding for nonprofit fair housing organizations that serve Latino communities raise further barriers [to fair housing]. Finally, the under-representation of Latinos in the enforcement system itself is a central concern, as is the perceived lack of responsiveness to Latinos at various stages within that system. Consequently, many Latinos are reluctant to file claims, believing that nothing will come of them . . . Native American advocates describe urban Indians as a forgotten minority and contend that government outreach to this group is minimal, leaving many Native Americans unaware of existing support services.”150 For recent immigrants, HUD’s Fair Housing Guide encourages Grantees to study “problems faced by immigrant populations whose language and cultural barriers combine with lack of affordable housing to create unique fair housing impediments;” HUD should ensure that meaningful efforts are made to address such impediments.151

XI. Conclusion

As HUD formulates AFFH guidelines for today’s communities, integration remains a compelling mandate. HUD should assess ways in which it can further integration for all ethnicities, particularly through improved data collection and robust impact assessment practices. In doing so, HUD will advance key aims of the Fair Housing Act, as well as endowing communities with the lasting benefits of both diversity and opportunity. The Opportunity Agenda would welcome the chance for additional discussion regarding these and other elements of fair housing and opportunity for all.

Notes:

1. U.S. Census Bureau, Rankings and Comparisons Population and Housing Table 1.

2. U.S. Dep’t of Commerce, Census 2000 Brief: The Asian Population 1 (Feb. 2002).

3. 42 U.S.C. § 3608(e)(5) (2010).

4. 42 U.S.C. § 3601 (2010).

5. Evans v. Lynn, 537 F.2d 571, 577 (1975) (citing 114 CONG. REC. 9563 (statement of Rep. Celler)).

6. Trafficante v. Metro. Life Ins. Co., 409 U.S. 205, 211 (1972) (citing 114 CONG. REC. 3422 (statement of Sen. Mondale)).

7. Id.

8. Gladstone, Realtors v. Bellwood, 441 U.S. 91, 112 (1979).

9. Havens Realty Corp. v. Coleman, 455 U.S. 363, 376-7 (1982) (acknowledging Gladstone’s precedent that standing could be granted on grounds of deprivation of the “benefits of interracial associations that arise from living in integrated communities free from discriminatory housing practices,” but remanding due to insufficiency of allegations on other grounds).

10. Linmark Assocs., Inc. v. Twp. of Willingboro, 431 U.S. 85, 95 (1977).

11. 114 CONG. REC. 2528; see also 114 CONG. REC. 2281.

12. See Clients’ Council v. Pierce, 711 F.2d 1406, 1425 (8th Cir. 1983).

13. Otero v. New York City Hous. Auth., 484 F.2d 1122, 1133-35 (2d Cir. 1973); Park View Heights v. City of Black Jack, 605 F.2d 1033, 1036 (8th Cir. 1979) (internal cites omitted), cert. denied, 445 U.S. 905 (1980); Metro. Hous. Dev. Corp. v. Vill. of Arlington Heights, 558 F. 2d 1283, 1290 (7th Cir. 1977), cert. denied, 434 U.S. 1025 (1978); Huntington Branch NAACP v. Town of Huntington, 844 F. 2d 926 (2d Cir.), aff’d per curium, 488 U.S.

14. Segregation of Asians and Latinos has also been addressed in the educational setting, as in: Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U.S. 78, 85 (1927); Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Indep. School District, 324 F. Supp. 599 (S.D. Tex. 1970); Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973); Gonzales v. Sheely, 96 F. Supp. 1004 (D. Ariz. 1951); Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475, 479-80 (1954); Santamaria v. Dallas Indep. Sch. Dist., 2006 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 83417 (N.D. Tex. Nov. 16, 2006).

15. 24 C.F.R. §§ 200.600 et seq. (2010).

16. 24 C.F.R. § 941.202 (2010); see also 24 § CFR 983.57 (2010), for similar language governing site selection for project-based voucher programs. See HUD NOTICE: H-09-19, issued Dec. 7, 2009, stating that since 2003, “‘[m]inority neighborhood (area of minority concentration)’ has been defined as one where any one of the following statistical conditions exist: (1) the neighborhood’s percentage of persons of a particular racial or ethnic minority is at least 20 percentage points higher than the percentage of that particular racial or ethnic minority in the housing market area; (2) the neighborhood’s total percentage of minority persons is at least 20 percentage points higher than the total percentage of minorities in the housing market area; (3) in the case of a metropolitan area, the neighborhood’s total percentage of minority persons exceeds 50 percent of its population. The term ‘non-minority area’ is defined as one in which the minority population is lower than 10 percent.” Note that “[s]o far as the court can determine, nothing in any statute, regulation, or policy, or the administrative record, defines ‘area of minority concentration’ or ‘racially mixed area.’ The lack of a statutory or regulatory definition leaves substantial room for HUD to interpret these terms.” Glendale Neighborhood Ass’n v. Greensboro Hous. Auth., 956 F. Supp. 1270 (M.D.N.C. 1996). See also Philip Tegeler, The Persistence of Segregation in Government Housing Programs, in Xavier de Souza Briggs, ed., THE GEOGRAPHY OF OPPORTUNITY (Brookings Institution Press 2005).

17. 24 C.F.R. § 1.4(b)(1)(iii) (2010).

18. Shannon v. HUD, 436 F.2d 809, 819 (3d Cir. 1970); see also Jaimes v. Toledo Metro. Hous. Auth., 715 F. Supp. 835, 839 (N.D. Ohio 1989); Project B.A.S.I.C. v. Kemp, 776 F. Supp. 637, 642 (D. R.I. 1991).

19. Gautreaux v. Romney, 448 F.2d 731 (7th Cir. 1971); United States ex rel. Anti-Discrimination Ctr. of Metro N.Y., Inc. v. Westchester County, 668 F. Supp. 2d 548 (S.D.N.Y. 2009).

20. Shannon v. HUD, 436 F.2d 809 (3d Cir. 1970). See also: Graves v. Romney, 502 F.2d 1062 (8th Cir. 1974); Altshuler v. HUD, 686 F.2d 472 (7th Cir. 1982); Project BASIC v. Kemp, 776 F. Supp. 637, 642-3 (D. R.I. 1991) (internal cites omitted); Pleune v. Pierce, 765 F. Supp. 43, 47 (E.D.N.Y. 1991).

21. NAACP v. Sec’y of Hous., 817 F.2d 149, 155 (1st Cir. 1987).

22. See Shannon v. HUD, 436 F.2d 809 816, noting that “in 1949 the Secretary…possibly could act neutrally on the issue of racial segregation. By 1964 he was directed…to prevent discrimination…In 1968 he was directed to act affirmatively to achieve fair housing.”

23. Id., citing Otero v. N.Y.C. Hous. Auth.. 484 F.2d 1122, 1134 (2d Cir. 1973).

24. Thompson v. HUD, 348 F. Supp. 2d 398 (D. Md. 2005). See also Florence Wagner Roisman, Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing in Regional Housing Markets: The Baltimore Public Housing Desegregation Litigation, 42 Wake Forest L. Rev. 333 (Summer 2007).

25. Langlois v. Abington Hous. Auth., 234 F. Supp. 2d 33, 77 (D. Mass. 2002); United States ex rel. Anti- Discrimination Ctr. of Metro New York, Inc. v. Westchester County, 668 F. Supp. 2d 548, 564 (S.D.N.Y. 2009).

26. Cf Walker v. City of Mesquite, 169 F.3d 973 (5th Cir. 1999), striking down a racially-based siting requirement for new housing in a Texas desegregation decree. The court found that the requirement that new construction be sited in majority-white areas was not narrowly tailored, as a formula based on poverty rates would be effective. See also discussion of Walker by Philip Tegeler, The Future of Race-Conscious Goals in National Housing Policy, in PUBLIC HOUSING AND THE LEGACY OF SEGREGATION (Margery A. Turner et al. eds., The Urban Institute Press 2009).

27. United States ex rel. Anti-Discrimination Ctr. of Metro New York, Inc. v. Westchester County, 668 F. Supp. 2d 548, 564 (S.D.N.Y. 2009).

28. HUD, Fair Housing Planning Guide at 2-28.

29. Id. at 5-17.

30. Id. at 2-11.

31. Id. at 3-6.

32. Trafficante v. Metro. Life Ins. Co., 409 U.S. 210 (1972) (while minority groups were damaged the most from discrimination in housing practices, the proponents of the legislation emphasized that those who were not the direct objects of discrimination had an interest in ensuring fair housing as they too suffered).

33. See, e.g., Gladstone, Realtors v. Bellwood, 441 U.S. 91 (1979); United States v. Sec’y of HUD , 239 F.3d 211 (2d Cir. 2001); Davis v. New York City Hous. Auth., 1992 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 19965 (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 30, 1992); NAACP v. City of Kyle, 2006 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 51226 (W.D. Tex. June 16, 2006); Hispanics United v. Vill. of Addison, 988 F. Supp. 1130 (N.D. Ill. 1997); Huntington Branch NAACP v. Town of Huntington, 844 F.2d 926, 937 (2d Cir. 1988); Anti-Discrimination Ctr. of Metro New York, Inc. v. Westchester County, New York, 668 F. Supp. 2d 548, 564 (S.D.N.Y. 2009); United Farmworkers of Florida Hous. Project, Inc. v. Delray Beach, 493 F.2d 799 (5th Cir. 1974); Jaimes v. Toledo Metro. Hous. Auth., 715 F. Supp. 835 (N.D. Ohio. 1989).

33. 24 C.F.R. §§ 200.600 et seq. (2010).

34. See Green v. County Sch. Bd., 391 U.S. 430 (1968); Bailey v. Ryan Stevedoring Co., Inc., 528 F.2d 551 (5th Cir. 1976).

35. See Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948); NAACP v. Town of Huntington, 844 F. 2d 926 (2d Cir. 1988).

36. Eva Dick, Residential Segregation of Immigrants on St. Paul’s West Side, 38 CURA REP. 1 (Spring 2008) at 10.

37. Id.

38. Camille Zubrinsky and Lawrence Bobo, Prismatic Metropolis: Race and Residential Segregation in the City of the Angels”, 25 SOC. SCI. RES. 335, 339; (1996) (citing Denton and Massey, 1988; Massey and Fong, 1990.); see also Ingrid Gould Ellen, Continuing Isolation: Segregation in America Today, in SEGREGATION: THE RISING COSTS FOR AMERICA 271 (James H. Carr et al. eds., 2008).

39. Maria Krysan & Reynolds Farley, The Residential Preferences of Blacks: Do They Explain Persistent Segregation?, 80 SOC. FORCES 3, 937-80 (2002).

40. Camille Z. Charles, Can We Live Together?, in The Geography of Opportunity at 59-61 (William J. Wilson et. al. eds., Brookings Institution Press 2005).

41. Lawrence Bobo, Attitudes on Residential Integration: Perceived Status Differences, Mere In-Group Preference, or Racial Prejudice?, 74 SOC. FORCES 3, 883-909 (1996).

42. David Card et al., TIPPING AND THE DYNAMICS OF SEGREGATION IN NEIGHBORHOODS AND SCHOOLS 25 (2006).

43. Id.

44. Morrison Wong, Chinese Americans, in ASIAN AMERICANS: CONTEMPORARY TRENDS AND ISSUES 137 (Pyong Gap Min ed. 2006).

45. Ellen, supra fn 38, at 272.

46. “In all likelihood, there are reciprocal effects with attitude shaping location decisions to as great an extent as resources, information, and other considerations allow, while the experience of particular neighborhoods, group relations, and status and service considerations then come to reshape attitudes.” Bobo, supra fn 41, at 900, 902 (citing Galster 1989; Sigelman & Welch 1993).

47. Id. at 904.

48. DOUGLAS S. MASSEY & NANCY A. DENTON, AMERICAN APARTHEID: SEGREGATION AND THE MAKING OF THE UNDERCLASS 91 (Harvard University Press 1993).

49. Id. at 104-105; describing study of how loan distribution had negative correlation with black populations in Dallas and Milwaukee neighborhoods, at 107.

50. Steven W. Bender, Knocked Down Again: An East L.A. Story, 12 HARV. LATINO L. REV. 109, 114-118 (2009). Covenants and their effects are also described in, E.g., Kevin R. Johnson, Hernandez v. Texas: Legacies of Justice and Injustice, 25 CHICANO-LATINO L. REV. 153 (discussing history of restrictive covenants and other discrimination against Japanese-Americans and Mexican Americans in California and Texas); see also Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. at 471, 481.

51. See In re Lee Sing, 43 F. 359 (N.D. Cal. 1890).

52. John Yen Wong, Still Separate and Unequal: A Public Hearing on the State of Fair Housing in America.

53. Amicus brief of AAJC et el. in Parents Involved v. Parents Sch. Distr. No. 1, 551 U.S. 701 (2007) (citing ART CHIN & DOUG CHIN, UPHILL: THE SETTLEMENT & DIFFUSION OF THE CHINESE IN SEATTLE, 39 (Shorey Original Publication 1973) (“[T]he Chinese moved into the First Hill and Beacon Hill areas [located in the central district] only because they were the only districts not covered by the restrictive covenant.”).

54. Nat’l Fair Hous. Alliance, 2008 Fair Housing Trends (2008).

55. Defined as those who spoke primarily Spanish at home.

56. Kathleen Engel & Patricia McCoy, From Credit Denial to Predatory Lending, in SEGREGATION: THE RISING COSTS 94 (James H. Carr et. al. eds., Routledge 2008).

57. Margery A. Turner et. al, Discrimination in Metropolitan Housing Markets: Phase 2 – Asians and Pacific Islanders (March 2003), at ii

58. Fair Hous. Council of Fresno County, Fair Housing Audit of Fresno County (1995); see also John Yinger, Evidence on Discrimination in Consumer Markets, 12 J. OF ECON. PERSP. 2, (1998).

59. San Antonio Fair Hous. Council, San Antonio Metropolitan Area Rental Audit (1997).

60. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Census 2000. (In 2000, Houston was 42% white, 25% black, and 37% Latino).

61. Daniel Bustamante, Executive Director of the Greater Houston Fair Housing Center, Testimony on Housing Discrimination in Houston, TX (hearings conducted by National Commission on Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity, 2008) at 2.

62. Turner et. al., supra fn 57, at 3-8.

63. Id.

64. Margery A. Turner et. al, Discrimination in Metropolitan Housing Markets: Phase 3 – Native Americans (Sept. 2003), at iii.

65. U.S. Bureau of the Census, We the People: American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States (2006; based on 2000 Census data), at 14;

66 See, e.g., MASSEY & DENTON, supra fn 48.

67. Gladstone, Realtors v. Bellwood, 441 U.S. 91, 112 (1979).

68. As one group of advocates phrased it in that context, “Ample studies have shown that exposure to students from a wide range of backgrounds enhances the educational experiences of all students, whether Caucasian American or minority. Thus, Asian Pacific American students, and all other students, benefit from racial and ethnic diversity… Achieving such diversity constitutes a compelling governmental interest.” Brief of Amici Curiae National Asian Pacific American Legal Consortium, Asian Law Caucus, Asian Pacific American Legal Center, et al. in support of respondents in Grutter v. Bollinger, et al., 539 U.S. 306 (2003) and Gratz, et al. v. Lee Bollinger, et al., 539 U.S. 244 (2003), on Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, in 10 ASIAN L.J. 295.

69. Xavier de Souza Briggs, More Pluribus, Less Unum? in THE GEOGRAPHY OF OPPORTUNITY at 24 (Brookings 2005).

70. Stacey Lee, The Truth and Myth of the Model Minority: the Case of Hmong Americans, in NARROWING THE ACHIEVEMENT GAP 171 (Paik et. al. eds. 2007).

71. See MEIZHU LUI ET AL., THE COLOR OF WEALTH (2006).

72. See The State of Opportunity in America (The Opportunity Agenda 2006) at 118-19.

73. Lisa Robinson and Andrew Grant-Thomas, Race, Place, and Home: A Civil Rights and Metropolitan Opportunity Agenda (Civil Rights Project 2004); (citing Jargowsky 2003).

74. Id. at 22.

75. Id. at 25.

76. See MASSEY & DENTON, supra fn 48, at 109, 161.

77. ANGELO ANCHETA, RACE, RIGHTS, AND THE ASIAN AMERICAN EXPERIENCE 113 (Rutgers Univ. Press 1998); see also Robert Teranishi, Southeast Asians, School Segregation, and Postsecondary Outcomes, (NYU Commission on Asian American Research in Higher Education 2004).

78. Lee, supra fn 70, at 172.

79. Id. at 135, 206 (citing data revealed by the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act).

80. JAMES H. CARR & NANDINEE K. KUTTY, SEGREGATION: THE RISING COSTS FOR AMERICA, at 121-23 (Routledge 2008).

81. Nat’l Fair Hous. Alliance, supra fn 54, at 22.

82. Engel & McCoy, supra fn 56, at 92.

83. Id. at 97-98.

84. Id. at 100.

85. Furman Center, The High Cost of Segregation: Exploring the Relationship Between Racial Segregation and Subprime Lending (November 2009); see also Jarrett Murphy, Race and Space: Segregation and Foreclosure in Huffington Post.

86. See, e.g., discussion in Mary Frances Berry et al., Not in My Backyard: Executive Order No. 12,898 and Title VI as Tools for Achieving Environmental Justice, (U.S. Comm’n on Civil Rights, 2003) at 13 et seq.