The U.S.-‐Mexico border and the communities surrounding it represent many things: billions of dollars in trade, shared histories and cultures between the countries, and home to millions of people. But these communities are also a pawn in political discourse and misguided calls to “secure the border,” all while avoiding a meaningful dialogue on reforming immigration policies and policing practices. The resulting buildup in border enforcement and policing has a profound effect on the individuals and families in the region, including those living up to 100 miles away from the actual border, and beyond. While this buildup disproportionately affects communities on our southern border with Mexico, many of Border Patrol’s misguided policies and tactics also affect the quality life for communities across our northern border with Canada. In fact, roughly two-‐thirds of the U.S. population lives within 100 miles of an international border.

This memo includes guidance for telling a story about policing in border communities that will bolster public opinion for positive policies that grow and sustain communities rather than policies that disrupt and divide them.

Current Public Opinion

Although policymakers most often connect border policy to conversations about immigration, it’s important to recognize that, for the millions of residents who call border communities home, holding U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) accountable to policing best practices is also a matter of promoting public safety and community trust. With roughly 44,000 armed officers, including Border Patrol, CBP is our nation’s largest law enforcement agency.

Support for increased enforcement in border communities is based on how politicians and the media portray those communities. The story that generates people’s concerns and bolsters support for enforcement is one of a chaotic border with little order, dangerous people, and drug and gang activities. That is not, however, the border region that most people living there would recognize. In fact, we know that most border residents feel safe in their communities, and that those communities are, in fact, among the safest in the country. 1 2

Misperceptions of border communities—and connecting their issues only to the larger debate about immigration—serve to fuel a dominant narrative that we must “secure the border.” As a result, we see a lack of support for commonsense policies at the border as current public opinion reflects concerns about the state of the border and translates to support for increased enforcement and policing.

We need to change the underlying story about border communities and policing in order to influence public opinion and change policy. Immigration advocates and others talking about border policies must move away from “border security first” messaging. We have to replace this failed messaging with an emphasis on economic opportunity, public safety, human rights, and community trust. Doing so will build opportunity for both immigration policy reform and policing reforms in border communities that put an end to military-‐style and discriminatory policing that offends American values of equality and justice. Below are three tips to consider when telling a new story.

1. Control the Context: Community vs. Chaos, People vs. Political Rhetoric

Telling stories about particular Border Patrol abuses and human rights violations is not sufficient to change the overarching story about the border region. As storytellers, it’s key to shape the entire narrative, centering it on stories about communities and people. That way, audiences have a picture in their heads of a community similar to their own, with similar concerns, challenges, and opportunities. It’s through this lens that they can better understand why excessive policing is a problem and why a militarized force is undesirable.

Sample Language

The border region is economically vibrant and culturally diverse. It’s home to millions of people, from San Diego to Brownsville, who want to be able to enjoy life in their communities the same as any of us. Families whose roots here go back centuries share the region with newcomers from around the country and around the world. It’s an economic cornerstone and international trade hub, and 1 in 24 jobs across the country depend on it. It is a region where responsible investment can be prosperous for the entire nation.

The border is more than a line. Millions of people live in border communities and many more know someone who does. Border communities have much to offer the nation economically and culturally, but these contributions have been stunted or overshadowed by an irresponsible buildup of border enforcement.

Focus on Goals, Values, and People

Research completed by a coalition of immigrant rights and border region groups in 2013 recommends relying on two main themes while telling this story: goals and people. Our goals should be to maintain the safety of our communities while upholding our values. And we should consistently insert people into the story to remind audiences that we are talking about communities, not barren desert or battle zones, as some of the rhetoric would suggest.

Goals: Values + Safety

We want immigration laws and law enforcement to uphold the American values of justice and fairness for all, while ensuring public safety. The current system is ineffective and it violates our values—it is unfair and inhumane.

People: Families, Workers, Children, Community Members

People sacrifice so much coming to America to make a better life, sometimes to escape desperate poverty and violence. Many are families with children. They work hard, pay taxes, and volunteer in their communities. They love America and want to contribute to our country.3

Border communities want safe, efficient, and effective border policies that respect the culture and community of the borderlands. When Border Patrol agents racially profile and detain community residents who are commuting to work and school at checkpoints located up to 100 miles away from the international border, their biased policing offends American values of equality and justice and hurts public safety by creating mistrust.

Additional Sample Language

Throughout the Southwest border region, there are urban and rural communities with deep roots and a long history of diversity, economic vibrancy, and cooperation. Border communities, like communities throughout the country, are entitled to human rights, due process, and policies that recognize their dignity, humanity, and the constitutional protections that this nation values.

Unfortunately, policymakers have far too often thrown border communities under the bus by pursuing policies that are ineffective and wasteful for security. These injustices, which go against equality, fairness, and law and order, are frustrating to Americans and completely avoidable. We can and should make commonsense policy changes to uphold human rights and due process in all of our communities.

We live in a democracy, and Americans strongly believe that we should all have a say in decisions that affect us. But when it comes to policies that affect border communities, policy makers often ignore community voices and needs. For example, over protests from the community, the border has grown increasingly more militarized as we dump money into drones, checkpoints, and guns. Instead, let’s look at policies that bolster trade and protect human rights at the border through investment in critical infrastructure projects and greater accountability for border agents.

2. Frame the Problem: A Threat to Values

Law enforcement abuses, excessive policing, and militaristic strategies on American soil are central issues in border communities, but they are only part of the problem. The core problem to focus on in telling a new story about border communities and policing is how these tactics threaten the values we hold dear as a country, including protecting due process and human rights, respecting the integrity of communities, and spending our resources wisely.

Rights Violations

Research shows that when talking about these issues, more people are persuaded by conversations that begin by examining what kind of country we want to live in and what kind of values we want to uphold, than by those starting with a focus on the rights of certain groups or individuals, or on specific rights violations—like illegal searches and seizures.

Community Disruption

Paint a picture of checkpoints and daily routines disrupted because of misguided enforcement. Show how racial profiling affects community members, and how law enforcement’s shameful treatment of U.S. citizens and immigrants in border communities does not reflect the kind of country we want to live in.

Sample Language: Op-Ed Excerpt

Unchecked abuse and corruption within Customs and Border Protection (CBP) must be part of any discussion regarding the US southern border and the time has come to talk about reforming the agency. The Obama administration has the means to move us forward and should do so immediately.

Earlier this summer, the administration released a report calling for significant reforms to CBP to prevent widespread corruption and expand much-‐needed oversight. CBP has come under increased scrutiny as a nationwide debate continues around law enforcement’s relationship to communities, especially communities of color.

For years, CBP has failed to hold its officers accountable when they use excessive force and kill unarmed civilians. The agency fails to document and report racial inequities in who its officers stop and search, and fails to detect and deter counterproductive racial profiling that undermines values of fairness and equality. These excesses infringe daily on the rights and dignity of border communities and their residents, who go about their daily lives up to 100 miles away from the physical border yet experience CBP permanent checkpoints and patrols in their neighborhoods. For example, a recent report based on more than 50 complaints in New Mexico and Texas discovered abuses such as racial profiling, unjustified searches and detentions, physical and verbal abuse, intimidation, and interfering with emergency medical treatment. Ninety percent of people reporting these abuses were U.S citizens and 81 percent were Latino.

These incidents are not isolated. An investigation by Politico Magazine found that “between 2005 and 2012, nearly one CBP officer was arrested for misconduct every single day;” that CBP rapidly recruited agents without proper vetting or supervision, making systemic misconduct highly likely; and that, by 2014, the number one criminal priority of the FBI’s McAllen, Texas office was investigating Border Patrol agents.

A review of over 800 complaints provided by CBP’s Office of Internal Affairs reveals that CBP failed to hold officers accountable in 97 percent of the cases in which Internal Affairs completed an investigation. Almost 80 percent of the total complaints are based on physical abuse or excessive force. The rest are based on abuses including misconduct, mistreatment, racial profiling, improper searches, inappropriate touching during strip searches, or sexual abuse. In May, the former Chief of Internal Affairs, James Tomsheck, came forth as a whistleblower, saying that he witnessed a “spike” of more than 35 sexual misconduct cases between 2012 and 2014 and an agency culture that ignored and swept away corruption. A lawsuit brought by mothers and children seeking asylum last summer alleged that CBP officers applied coercion to dissuade them from getting an attorney and asserting their legal rights, in violation of domestic and international law.

Unacceptable Tactics: Racial Profiling

Explain why profiling harms us all, not just people of color or immigrants. This includes harm to our national values of fairness and equal justice, harm to public safety, and harm to Americans who are wrongly detained, arrested, or injured by law enforcement.

- To work for all of us, our justice system depends on equal treatment and investigations based on evidence, not stereotypes or bias.

Define the term racial profiling and fully explain that it is based on stereotypes and not evidence in an individual case. Explain why racial profiling is not an effective police tool and is a rights violation, and counter those who believe racial profiling may be acceptable if it somehow keeps communities safe.

- Too often, law enforcement, including Border Patrol, use racial profiling, which is singling people out because of their race or accent, instead of based on evidence of wrongdoing. That’s against our national values, endangers our young people, and reduces public safety. Border Patrol—part of our nation’s largest police force—should stop claiming to play by different rules than those expected of local police and hold its agents accountable to end this ineffective, harmful practice.

Offer multiple real-‐life examples. The idea of racial profiling is theoretical for some audiences. It’s important to provide multiple examples that include “unexpected” people of color—e.g., business people, faith leaders, honor students—who’ve been wrongly stopped.

Wrong Priorities: Misguided Spending

Current border policies and spending violate our values. We are a country that believes in community, fairness, and human rights. But misguided policies that allocate spending toward drones, weapons, and family detention facilities do not uphold these values.

Sample language

- For decades, failed border enforcement policies have exacerbated migrant deaths, destabilized local economies, and debilitated protections to civil liberties.

- Instead of pouring more money into unnecessary and excessive drones and police forces, we need investments in the ports-‐of-‐entry and infrastructure. Instead of giving Border Patrol free reign and tacitly accepting human rights violations, we need to hold agents accountable and charge them with protecting human rights.

3. Redirect: Talk Choices and Alternative Solutions

Remind audiences of the goals for any policing policy: what does any community want and need from law enforcement? Safety, respect, transparency, and accountability.

When people are detained or profiled, we want to make sure they are treated fairly and that law enforcement respects rights like due process, equality before the law, and access to courts and lawyers—bedrock American legal values.

Keep Solutions Front and Center

Audiences need ideas about what does work and they don’t respond well to attacks on bad policies alone. The public does not respond well if they believe a speaker is only suggesting that existing laws not be enforced and conversations without positive solutions can quickly turn to support for enforcement measures.

Instead, focus on and give context to everyday border residents—college students, mothers and fathers, or business owners—who feel the effects of biased and military-‐ style policing by Border Patrol and are relatable to your audience. Americans understand that policing based on evidence versus bias is not only more effective, but also upholds our values of fairness and equality. Many communities nationwide also relate to concerns of military-‐style policing that emphasize using force over prioritizing de-escalation and protecting the paramount value of human life. When we contextualize Border Patrol abuses as offending our values and hurting everyday border residents, we help our audience broaden their lens and understand more fully who is affected by irresponsible policing practices.

Clearly State Who Should Do What

We need to assign responsibility when talking solutions, making sure we are clear about what we are asking of different entities.

Sample Language

- The White House should direct the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to prohibit the use of racial profiling. CBP should document racial and other inequities in who officers stop, question, and search and publicly share that data. It should also train its officers on Fourth Amendment protections against illegal searches and seizures, on prohibitions against racial profiling, and on implicit bias.

- CBP should scale back military-‐type tactics and equip its officers who interact with the public with body-‐worn cameras paired with privacy protections. CBP should also reduce its zone of operations from 100 to 25 miles from the actual border, and determine in which areas an even shorter distance is reasonable.

- DHS should establish an independent Border Oversight Task Force that includes border communities and has subpoena power over government officials so it can investigate and hold accountable abusive officers. It should also mandate greater oversight in order to end inhumane detention conditions; physical, sexual, or verbal abuse; and inadequate access to medical care. These are just the first steps of many that should be taken.

1. Border Network for Human Rights, Polling Report

2. USA Today, On Border Violence

3. Southern Border Communities Center; CAMBIO, Updated Narrative Messages

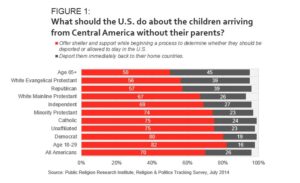

In 2014, The Opportunity Agenda commissioned a groundbreaking nationwide survey to examine what the U.S. public thinks about opportunity in America and to measure public support for policies that expand opportunity across a range of issues, including jobs, education, criminal justice reform, immigration, and housing. Additionally, the research sought to gain a deeper understanding of the multiple factors that influence attitudes on inequality, contribute to an individual’s worldview, and predict people’s willingness to take action on issues they care about. Together, the survey’s findings offer critical insights for social justice leaders and organizations seeking to move hearts, minds, and policy.

In 2014, The Opportunity Agenda commissioned a groundbreaking nationwide survey to examine what the U.S. public thinks about opportunity in America and to measure public support for policies that expand opportunity across a range of issues, including jobs, education, criminal justice reform, immigration, and housing. Additionally, the research sought to gain a deeper understanding of the multiple factors that influence attitudes on inequality, contribute to an individual’s worldview, and predict people’s willingness to take action on issues they care about. Together, the survey’s findings offer critical insights for social justice leaders and organizations seeking to move hearts, minds, and policy.