The vast majority of the social science literature on this topic focuses on problems relating to black males and the media, and is essentially descriptive — that is, it describes and analyzes existing patterns in the media, and in thought and behavior. Since there are so many current patterns that are problematic, much of the scholarship focuses on discovering the scope and details of the problem.

Prescriptive studies are relatively scarce in the literature, especially those that explicitly set out to determine, through the use of empirical evidence, how communicators (in the broadest sense) ought to be addressing the problems and handling relevant topics. The lack of prescriptive social science is related to the gap between theorists and activists noted in Charlotte Ryan’s analysis, “Building Theorist-Activist Collaboration in the Media Arena: A Success Story”:

As currently organized, academic-based framing theory focuses on frames as fossils – the products or remnants of political discourse. Framing theorists rarely involve themselves in a sustained fashion with working framers, the processes framers employ, or the audiences they mobilize. (Ryan, 2005)

This section reviews these areas where research is thin, if available at all.

Little “Good News” About Media Effects

The studies referred to earlier in this report paint a picture of a deep and complex problem. A distorted portrayal in the media taken as a whole leads to flawed and biased thinking about black boys and men, which in turn leads to significant real-world consequences of various kinds.

Much less apparent in the social science literature is evidence of the good effects that may be created by promoting new patterns of media portrayal. What happens when representation is fuller and more accurate, and more sympathetic? What kinds of media patterns help make people less biased, or lead to better outcomes? What is the evidence (if any) about what “works”? While it is implicit in much of the discussion that changes in the media should lead to beneficial outcomes, there is very little evidence cited on this point.

One exception is political scientist Shanto Iyengar’s influential study of the effects of television news choices on viewers’ attitudes (Is Anyone Responsible? How Television Frames Political Issues). In an experimental setting, Iyengar showed subjects different types of news stories focusing on African Americans, embedded within longer news segments, focusing on a variety of topics. Subjects were then asked a series of questions regarding their racial attitudes, and the responses were compared based on whether subjects had seen “episodic” stories, coverage focusing on individuals rather than larger trends or forces, or “thematic” stories, focusing on broad, systemic patterns. The result:

News coverage of black poverty in general and episodic coverage of black poverty in particular increases the degree to which viewers hold individuals responsible for racial inequality. News coverage of racial discrimination has the opposite effect [emphasis added]. (Iyengar, 1991, p. 67)

That is, focusing on the outcomes for individuals ends up promoting counterproductive perspectives, while coverage that focuses on systemic discrimination can help move attitudes in a positive direction. Of course, coverage of the latter type is all too rare, as previously noted.

How to Influence the Media

While some advocates and other actors report successes in influencing media patterns, such as the Maynard Institute’s efforts to raise journalists’ awareness of how they cover race, the review uncovered no social science literature on the topic of how to effectively intervene in the media. That is, while various social scientists have pointed to the need to change various patterns, there is little guidance available from the research about how to insure the greatest likelihood of success in these efforts.

Clearly, some patterns have changed for the better over the generations, presumably in connection with broad cultural shifts in attitude. But how can advocates most effectively address the media in the contemporary context?

Good News from the Laboratory

A review of the relevant literature reveals a large number of social science studies that shed light on hypothetical ways in which the media might potentially help reduce bias against black males. While these studies do not look directly at media or public discourse — and are often not targeted at consideration of black males per se — this large body of research on how to reduce bias effects should certainly be of interest to communicators pursuing the same goal on a societal scale.

For instance, one finding that is intriguing, if difficult to apply, is that exposure to comedy (no matter what the subject of the comedy is) appears to make it easier to distinguish other-race faces from each other, a task that can be quite difficult depending on the subject’s life experience. The mechanisms are unclear here, and may have to do with links between positive emotional states and cognitive performance overall — i.e., not relating to race in particular. (Johnson & Fredrickson, 2005)

A brief review of some other important examples from the literature follows.

Individuation

Psychology researchers have investigated various “individuation” procedures that can reduce unconscious bias against African Americans, e.g., as measured in Implicit Association Tests. (Implicit bias is measured in tasks where reaction times are so fast that conscious consideration is not possible, and often in contexts where it is impossible for subjects to be aware that racial thinking is being tested.) For instance, when white college students receive hours of practice in distinguishing one black face from another, they ultimately show significantly reduced implicit bias, presumably because practice in thinking of blacks as individuals reduces the unconscious tendency to see them in terms of stereotypes. (Lebrecht, Pierce, Tarr, & Tanaka, 2009)

This individuation practice is helpful because researchers note that whites’ unconscious bias against black faces may well represent a default mode of thinking, i.e., “category-based” thinking, in which people are automatically thought of in terms of (often stereotypical) group characteristics — based on age, gender, or race, for instance. (Wheeler & Fiske, 2005)

In another study, subjects were asked to look at a photo of an unknown black face and guess whether the individual would like a particular vegetable (with no particular cultural or emotional significance). In this context, implicit bias was eliminated. The results contrast with a study in which subjects were asked to think about the black individual’s age, which appeared to trigger default, category-based perception. Thinking of the face as belonging to an individual with particular tastes works against unconscious bias and stereotypical thinking.

Explicitly “breaking the habit”

Other researchers have found that explicit training in rejecting stereotypes can help to reduce unconscious bias. Study participants who spent roughly 45 minutes doing tasks such as clicking “No” when viewing a black face paired with a stereotypical description (positive or negative) later showed a reduction in their implicitly measured bias — i.e., reaction times so fast they could not have been consciously controlled. Promisingly, the researchers found in a related task (focusing on biases about skinheads) that effects last for at least 24 hours. On the other hand, the researchers found that significantly briefer training periods had no effect — they liken the training to skill learning that requires repeated and intensive practice. (Kawakami, Dovidio, Moll, Hermsen, & Russin, 2000)

In one of the studies most directly related to media (Ramasubramanian, 2007), the researcher examined the effects of a combination of explicit training about stereotypes, plus examples that implicitly worked against stereotypes. Participants saw one of two twelve-minute videos that either explicitly advised them about media stereotypes (the “media literacy” video) or did not (the “control” video). They then read and summarized five brief written news stories, including two that contained either stereotypes about black males (relating to violence and unemployment) or counter-stereotypes (focusing on “gentleness and entrepreneurial success”). Following these exercises, they participated in a standard type of “lexical decision task” in which faster recognition of stereotype words (e.g., lazy, poor, uneducated) indicates that a stereotype is active in the mind. The results indicated that a combination of “media literacy training” plus seeing counter-stereotypical news stories reduced the activation of negative stereotypes — though neither by itself had this effect.

Reflex training

Experimental researchers have also found that study participants asked to internalize a particular new reflexive response can eliminate unconscious bias in contexts where it usually occurs. For instance, some subjects in the police simulation task discussed earlier were instructed to focus beforehand on the idea that they would think “safe” (rather than “quick”) when seeing a black face, and this procedure ended up reducing or eliminating the tendency to “shoot” more unarmed black males. (Stewart & Payne, 2008)

Note that this type of concrete reflex training procedure proves more effective than training officers not to be biased or not to shoot innocent people.

In another study, subjects were asked to repeat the following to themselves three times and then type it out (and told that this would improve their performance): “If I see a person, then I will ignore his race!” And in fact, these subjects too were able to perform the “shooter” task without race-based bias. (Mendoza, Gollwitzer, & Amodio, 2010)

Importantly, this if-then type of reflex training seems more effective than more “abstract” training in avoiding biased behavior.

Reducing stereotype threat

Researchers have designed controlled experiments to explore communications approaches that can lessen the impacts of stereotype threat, especially in tasks related to educational success. For example, teaching college students that intelligence is malleable rather than fixed (Aronson et al., 2002) or that race is socially constructed rather than biological (Shih et al., 2007) reduces the effects of stereotype threat considerably; and teaching people about the nature of stereotype threat itself has shown benefits. (Johns et al., 2005)

While this experimental work does not directly address public/media communications, there is reason to think that some of the lessons from this research could be applicable to changing the way that both blacks and non-blacks interact with stereotypes.

Motivation

Another body of studies has focused on the kinds of motivation that help people overcome prejudiced responses. For instance, several have suggested that guilt can be an effective tool for learning to reduce automatic bias. When whites are told that they have had negative reactions to unknown black faces, their level of implicit bias tends to go down when they are tested again. (Monteith, Ashburn-Nardo, Voils, & Czopp, 2002)

The important caveat is that this is much more true for people who already have internal motivation to think and act in a less biased way — i.e., people who truly do not want to be biased. This pattern was confirmed in a study that combined an explicit survey of racial attitudes with a test of implicit bias. Whites with an internal belief that bias is wrong, but who were not motivated strongly by external judgment of their racial behavior, showed the least signs of implicit bias. (Devine, Plant, Amodio, Harmon-Jones, & Vance, 2002)

On the other hand, externally imposed guilt can backfire: Researchers reviewing a body of literature on intentional “stereotype suppression” — i.e., experiments where participants were explicitly asked not to think in biased ways — conclude that this often leads to a “rebound effect,” meaning that prejudiced racial thinking can emerge more strongly after being suppressed for a particular interval, particularly when the suppression is based on the idea of being judged by others. (Devine & Sharp, 2009)

In short, censure may be an effective tool for eliminating some types of prejudiced behavior in some contexts, but it is not an effective tool for changing damaging patterns of thinking overall.

While these findings suggest potential directions for advocates — e.g., to avoid messages that focus on censure, or to promote programs to “train” Americans to reject bias — other kinds of work are needed in order to take the types of insights described in this section and apply them effectively to the design of real-world communications.

Messaging

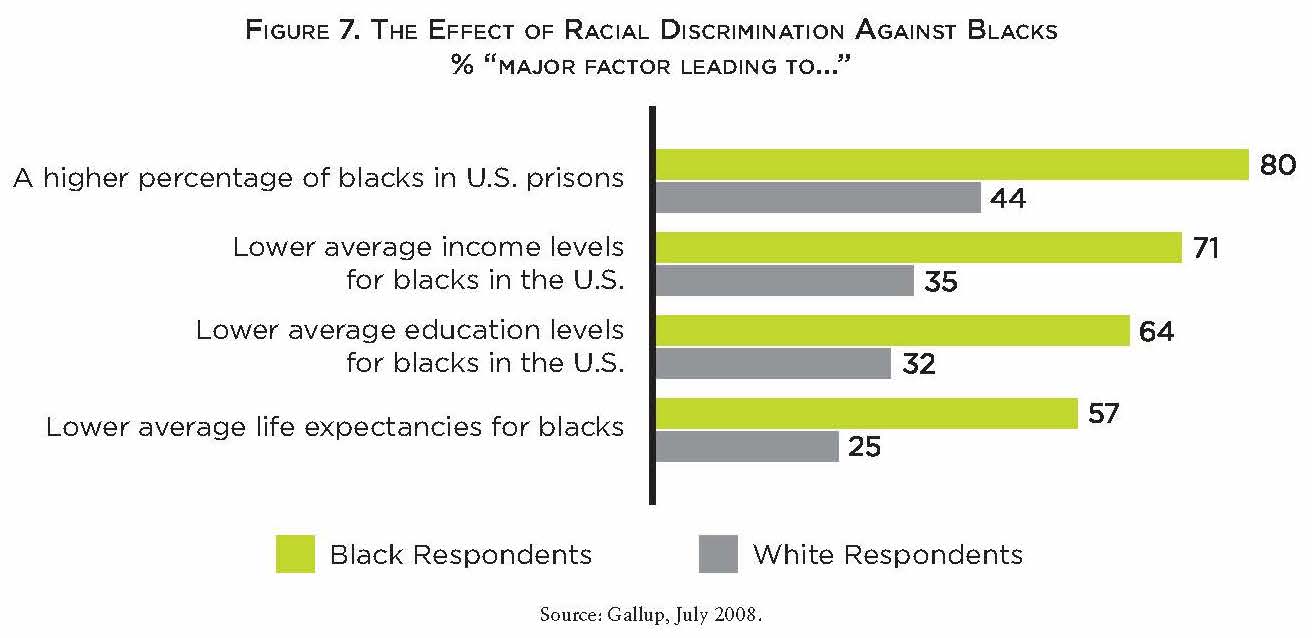

Another virtual gap in the social science literature concerns messaging per se — i.e., what to say about the issues, how to talk effectively about topics such as racial disparities, structural racism, lingering historical effects, and even the media problem itself (as discussed in section 1). There is substantial research on various dimensions of portrayal, but very little on how to talk about or explain key points.

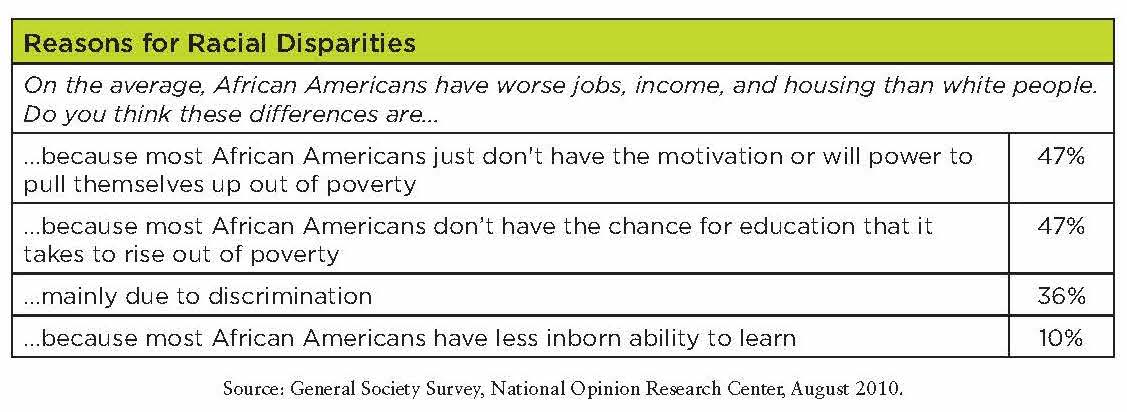

There are certainly some hints in the literature, of course, including learning from public opinion research (which is the focus of the companion report to this social science review). For instance, it seems clear that whites respond more negatively to policy proposals that are framed as helping one group (blacks) at the expense of others, in part because these seem unfair to them, and in part because whites are cued to consider their own self-interest when considering the proposals. (Bobo & Kluegel, 1993)

Confirming this pattern, a study by Franklin Gilliam showed that participants exposed to an explicit statement about the need to treat minorities more “fairly” ended up having the most negative views of policies such as the Earned Income Tax Credit or low-cost home loans for minorities. Some participants read a statement that included the following:

Whether overtly or more subtly, minorities are treated differently when it comes to such things as getting ahead in the classroom, applying for a home loan, and being able to see a doctor. According to this view, we need to renew our commitment to a just society by devoting more resources to policies that recognize and address fairness in our society. (Gilliam, 2008)

These participants ended up having more negative views of various supports for minorities than participants who saw no such statement or ones who saw statements less overtly geared to helping minorities. Indeed, years of public opinion data confirm the general pattern that whites tend to have a special antipathy for programs specifically targeted at helping blacks. (Steeh & Krysan, 1996)

On the other hand, some researchers echo many advocates’ discomfort with avoiding the topic of race. For example in the context of welfare reform:

There may be good reasons for advocates of a racially fair welfare system to avoid invoking race or highlighting the disproportionate presence of black recipients on the welfare rolls. On the other side, however . . . such a strategy risks participating in the silence that surrounds racial inequity in the United States; it fails to name or challenge the social and economic processes that make persons of color more likely to need public assistance. (Schram, 2003)

But the central question for this review concerns evidence about which strategies are likely to be effective, and there are at least some indications that communicators don’t need to avoid the topic of race in order to be successful.

In one of the few social science studies addressing effective messaging practices that mention race explicitly, Gilliam and Manuel conclude that directly addressing race can be effective if communicators emphasize broad values, rather than focusing more narrowly on discrimination. The researchers found, using a national web-based survey, that messages focusing on ideas like prevention, problem-solving, and strengthening all communities do more to promote health and youth-development policies for minorities than messages focusing on how African Americans receive unfair treatment. (Gilliam & Manuel, 2009)

The more effective messages included statements like the following:

[P]reventing problems in African American communities is important because they will eventually become everyone’s problems. Preventing declining school budgets, restrictive lending practices, and a scarcity of health professionals in African American communities will prevent worse problems in the future.

[E]ffective solutions do exist. Progress can be made if programs are routinely evaluated and the good ones brought to scale in African American communities. … smart states have significantly improved conditions in some African American communities … by raising teacher quality, creating lending policies for buying homes, and increasing the number of health professionals.

The reality is that African American communities are not enjoying the same benefits as the rest of the nation. This happens because the efforts that enhance a community’s well-being, like economic development, availability of health care programs, and opportunities for a good education, have not benefited African American communities.

Most other discussions of effective references to race are not social science studies per se. For example, after looking at multiple examples of successful and unsuccessful affirmative action campaigns in several states, the Center for Social Inclusion’s report “Thinking Change” concludes that, “If the goal is to educate the public about racial and gender unfairness to create long-term support for race and gender-conscious programs, the evidence seems to suggest that race-neutral strategies will fail.” (Note that while this CSI document is not a social science study, it is informed by many of the same studies as reviewed in this report.)

As “Thinking Change” points out, the city of Houston was able to fight back an anti-affirmative action ballot initiative through messaging that explicitly referred to race, though not to blacks. The white mayor repeatedly made the point that “Anglo male contractors got between 95 percent and 99 percent of the business before the affirmative action program got started 12 years ago. Today, they still get 80 percent.”6

The mayor’s argument effectively neutralizes both the fairness and zero-sum perspectives that often stand in the way of support for affirmative action, by emphasizing that whites still get the lion’s share of contracts. Another important reason for its success is almost certainly the mayor’s voice itself. If whites feel confident their interests are being understood and looked after, they are less likely to respond negatively.

This example is a hopeful one, but the authors acknowledge that many factors combine to determine the success of a race-related campaign, such as the particular issue at stake, the messengers, and the organizational effectiveness of each side.

In “Moving from Them to Us: Challenges in Reframing Violence among Youth” (Berkeley Media Studies Group), Dorfman and Wallack discuss a promising framework for discussing issues relevant to black males (and particularly youth):

The structural racism framework offered by legal scholars Andrew Grant-Thomas and john powell provides a much more complete understanding of the origins and consequences of racism. In this view, whether a person thrives in society is dependent upon the opportunities available, and opportunities are “produced and regulated by institutions, institutional interactions and individuals” together. Those interactions among institutions have a certain gestalt. Scholars liken it to a bird in a birdcage because it’s the network of bars working together, not a single bar, that traps the bird. (Dorfman & Wallack, 2009, p. 11)

While there is no reason to disagree that this bigger-picture perspective is desirable, there is little available evidence about how to talk about it in ways that effectively engage mainstream audiences and change their thinking.

For the moment, although some current “how-to” books for messaging in support of racial justice are informed by social science insights — see for example, the guides by Wallack et al. (1999) and Cutting and Themba-Nixon (2006) — these works rely mostly on the experience of practitioners rather than systematic research testing of practices and results.

6 The CSI report draws on a Berkeley Media Studies Group report (A New Debate on Affirmative Action: Houston and Beyond, 1998), which in turn quotes Mayor Bob Lanier from The Houston Chronicle, Oct. 26, 1997.