Perceptions of and by Black Men

Since the mid-20th century, the United States has seen an enormous shift in public attitudes toward black-white relations, segregation, and blatant prejudice. At the same time, racial tensions, obstacles, and stereotypes continue, and Americans of different racial and ethnic backgrounds hold divergent understandings of discrimination and the causes of racial disparities.3

Besides contributing to a negative civic environment, stereotypes matter because they may undermine support for efforts to reduce racial disparities. If white people view African Americans as lazy, they are less likely to support government anti-poverty programs. Or, if it is commonly believed that black people are unintelligent or violent, it will hinder efforts for school or neighborhood integration, for example. And if black people believe these negative things about their own group, it may contribute to low self-esteem and other problems.

Public opinion research suggests that positive and negative views toward black people may be grounded in multiple arenas. In other words, while one might assume that a particular experience or aspect of a person’s background would cause an individual to feel either positively or negatively toward a racial group, or to ascribe to one of two opposing views (black people are hardworking or lazy, etc.), research suggests that responses toward a racial group may have different antecedents and be multifaceted.

For example, in research conducted by Patchen, Davidson, Hofmann, and Brown in 1977, they found that:

Positive behaviors toward black people are predicted by racial contact, while negative behaviors are predicted by aggressiveness and family/peer racial attitudes.

Lipset and Schneider, in their 1978 analysis of the Bakke case, and Katz and Hass in their study of “Racial Ambivalence and American Value Conflict” (1988) found that:

Positive attitudes toward black people are based in humanitarianism (sympathy toward the disadvantaged), while negative attitudes are based in individualism (self-reliance).

The conscious attitudes about racial and ethnic groups reviewed in this section probably tell only one small part of the story, and subsequent sections (for example, discussions of personal responsibility and altruism) are highly relevant to attitudes of racial groups as well.

Though it has become less of a focus in recent years, public opinion research has at times measured public assessments of different racial groups, including their character traits. For example, when a Harris poll (2009) asked respondents to rate various racial and ethnic groups on a thermometer scale “with 1 meaning extremely negative and 100 meaning extremely positive,” Americans overall give the highest ratings to “white Americans” (83.2) and the lowest ratings to “Hispanic/Latino Americans” (77.7). Respondents give almost identical ratings to “Black/African Americans” (79.9), “Chinese Americans” (79.9), and “Asian Americans” (79.7).

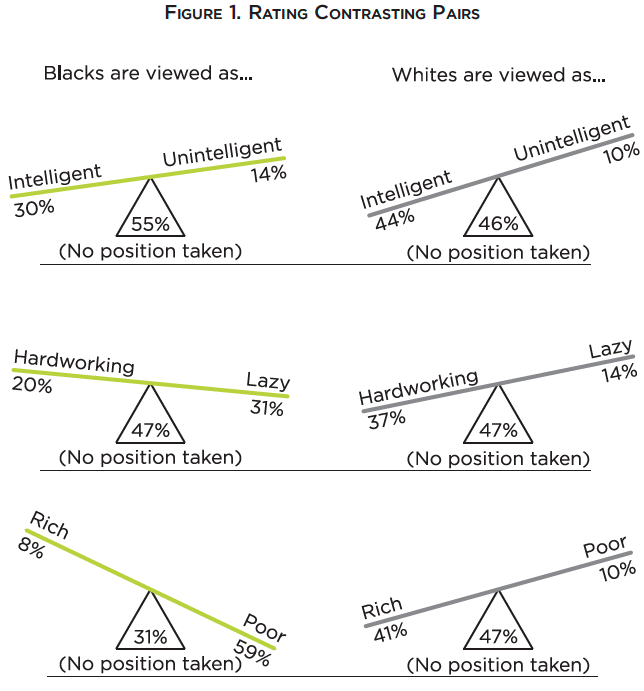

Many studies over the years have found that people are willing to assess groups on a variety of image traits with no description other than racial category. In research done by the National Opinion Research Center in 2010, people were asked to place racial groups on a 1 to 7 scale, with one end of the scale anchored by a particular trait and the other anchored by its opposite trait. Pluralities of survey respondents opted out of rating blacks or whites on intelligence, work ethic, and (to a lesser extent) wealth. However, of those who did give ratings, more said whites are intelligent than said blacks are intelligent (44 percent gave “intelligent” ratings for whites, 30 percent for blacks), and the same pattern held for “hard working” (37 percent for whites and 20 percent for blacks), and “rich” (41 percent and 7 percent, respectively) (see Figure 1).

Source: National Opinion Research Center, August 2010

More black men experience significant challenges than white men, have higher levels of worry, and are harsher in their judgment of black men. Even so, more are focused on achieving success in a career, on living a religious life, and are optimistic about a bright future. In just about every area, black men are their own harshest critics, as well as the most optimistic that things will get better.

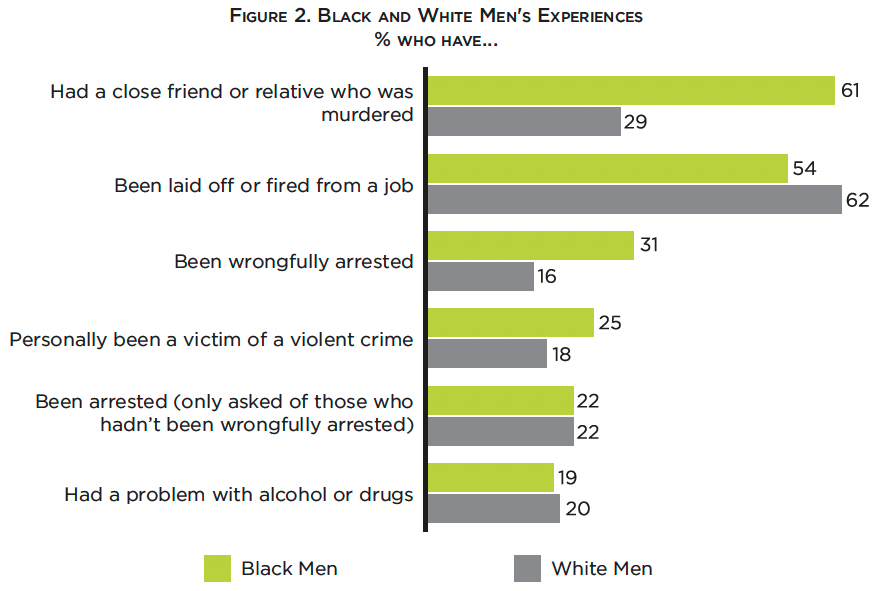

Many black men have faced traumatic experiences in their lives. In a Washington Post/Kaiser Family Foundation/Harvard 2011 study entitled “The Race and Recession Survey,” more black men than white men report having a close friend or relative who was murdered (61 percent and 29 percent, respectively), wrongfully arrested (31 percent, 16 percent), or the victim of a violent crime (25 percent, 18 percent). In only one area surveyed in this study have more white men than black men experienced a challenge — getting laid off or fired from a job (62 percent of white men, 54 percent of black men), a gap closed since the start of the recession (see Figure 2). Now, 27 percent of black people and 21 percent of white people say they have been laid off or lost a job in the past year, and more black people than white people say they are unemployed (44 percent and 40 percent, respectively) or underemployed (17 percent and 12 percent, respectively).

Source: Washington Post/KFF/Harvard, April 2006

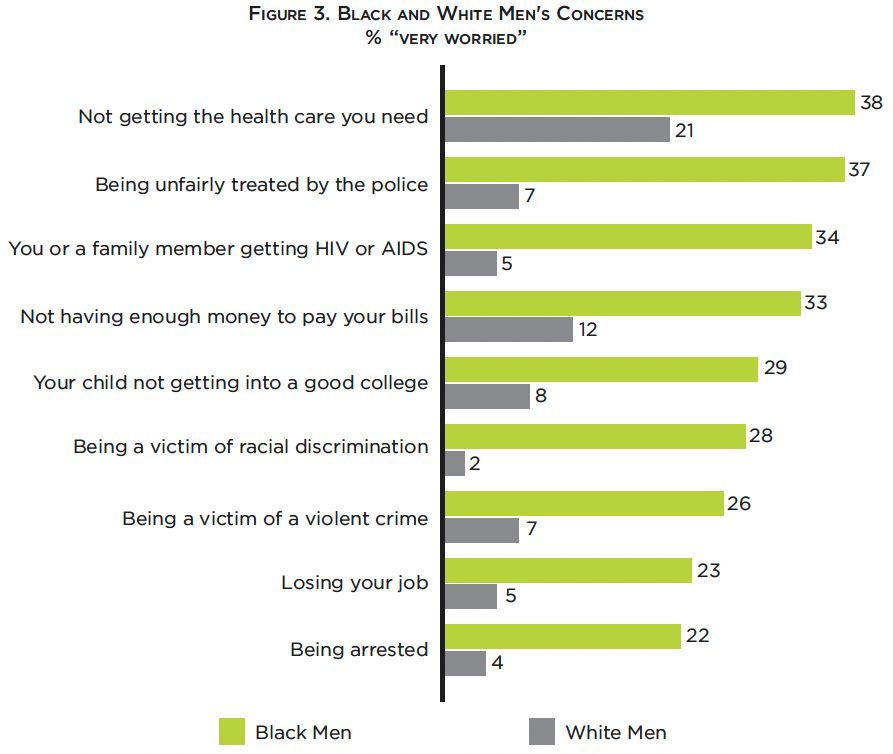

It follows that more black men cite high levels of worry about a range of concerns. Compared with white men, more black men are worried about every problem surveyed, from access to health care to getting arrested. A note of caution: This particular set of findings is based on a survey that occurred two years prior to the economic crash in 2008. It is highly likely that the same questions today would show far higher levels of worry on most measures, but particularly on economic measures. Important dynamics would likely remain unchanged: the gap in levels of worry between white and black men, as well as the high levels of worry on multiple issues among black men (see Figure 3).

Source: Washington Post/KFF/Harvard, April 2006

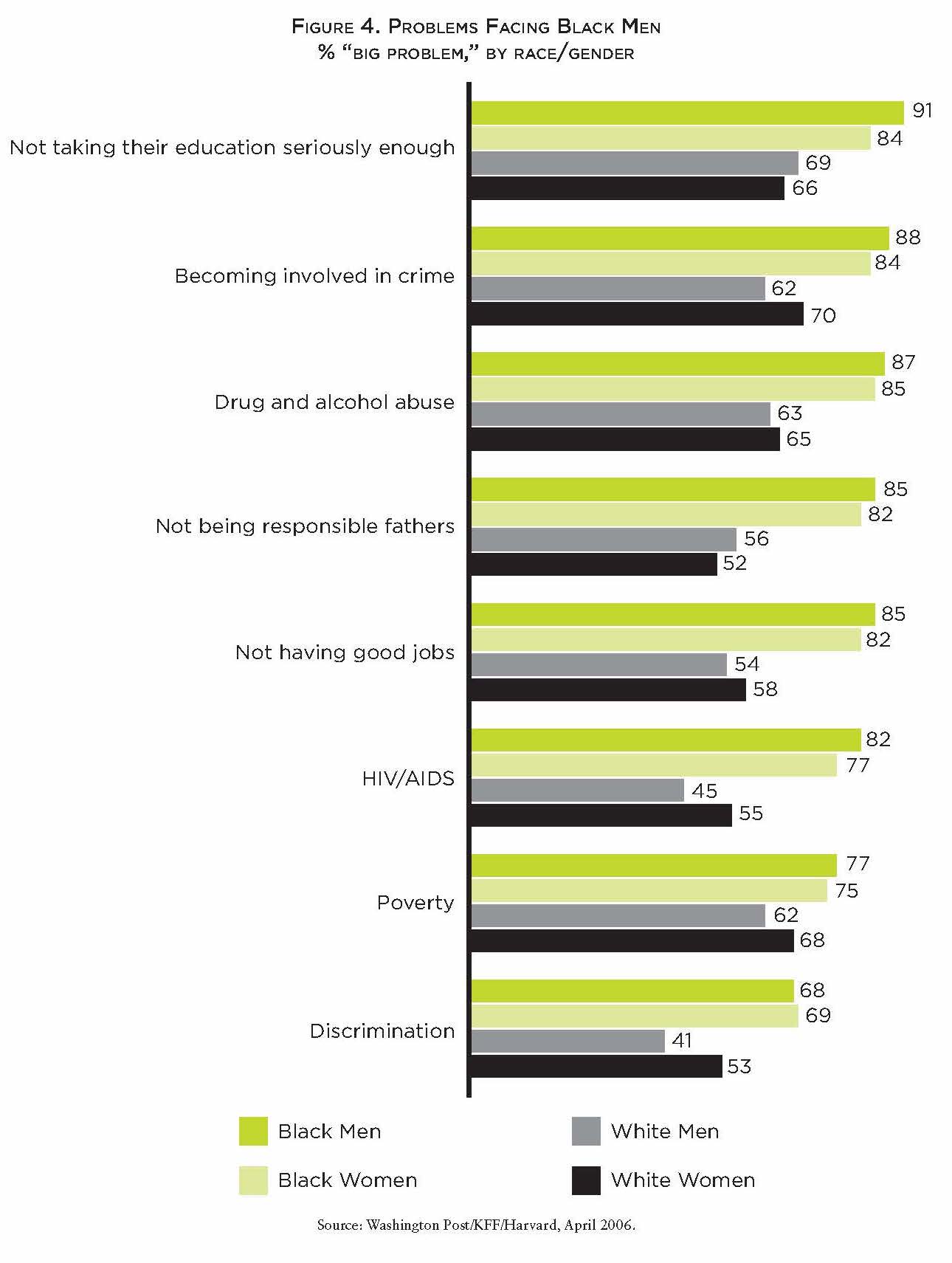

According to the 2006 Washington Post/Kaiser Family Foundation/Harvard study, “African American Men Survey,” in rating a series of problems facing black men, black men themselves are more likely than other audiences to rate a range of problems facing them as severe, including not taking education seriously enough (91 percent), becoming involved in crime (88 percent), drug and alcohol abuse (87 percent), not being responsible fathers (85 percent), not having good jobs (85 percent), HIV/AIDS (82 percent), poverty (77 percent) and, lastly, discrimination (68 percent) (see Figure 4). Black women’s ratings are similarly high, while white men and women are not as grim in their assessment of the problems facing black men. Asked to choose the single biggest problem facing black men, 31 percent of black men chose “not taking their education seriously enough.”

Source: Washington Post/KFF/Harvard, April 2006

Note that many of these “problems” — not taking their education seriously enough, not being responsible fathers, becoming involved in crime, etc. — can be read as admonishment of black men or black families. Black men are their own harshest critics in this regard.

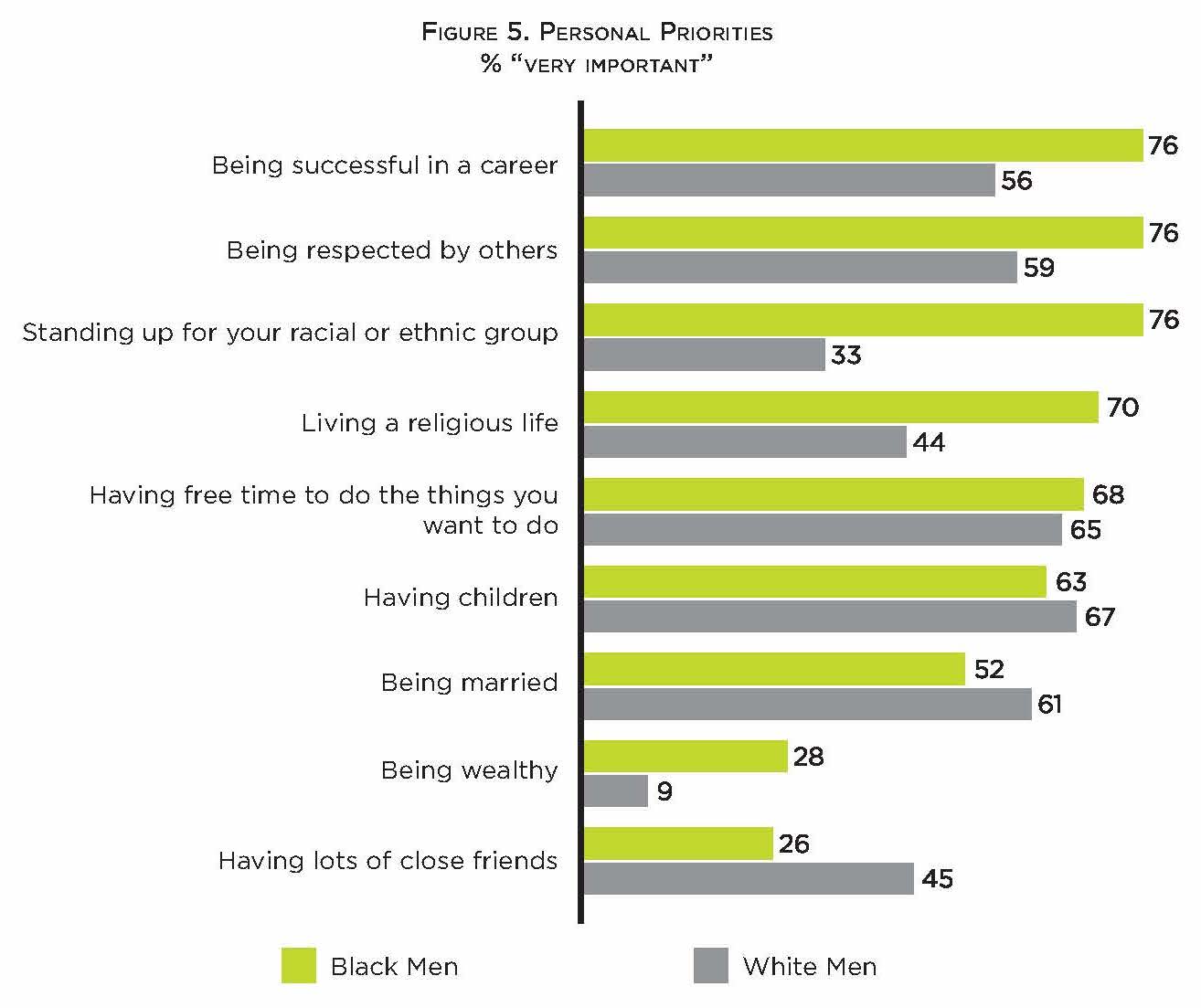

Black men and white men report very different priorities. For example, according to the Washington Post/KFF/Harvard 2006 study, compared with white men, black men put more importance on being successful in a career (76 percent of black men, 56 percent of white men), living a religious life (70 percent, 44 percent), being respected by others (76 percent, 59 percent), and standing up for their racial or ethnic group (76 percent, 33 percent) (see Figure 5).

Source: Washington Post/KFF/Harvard, April 2006

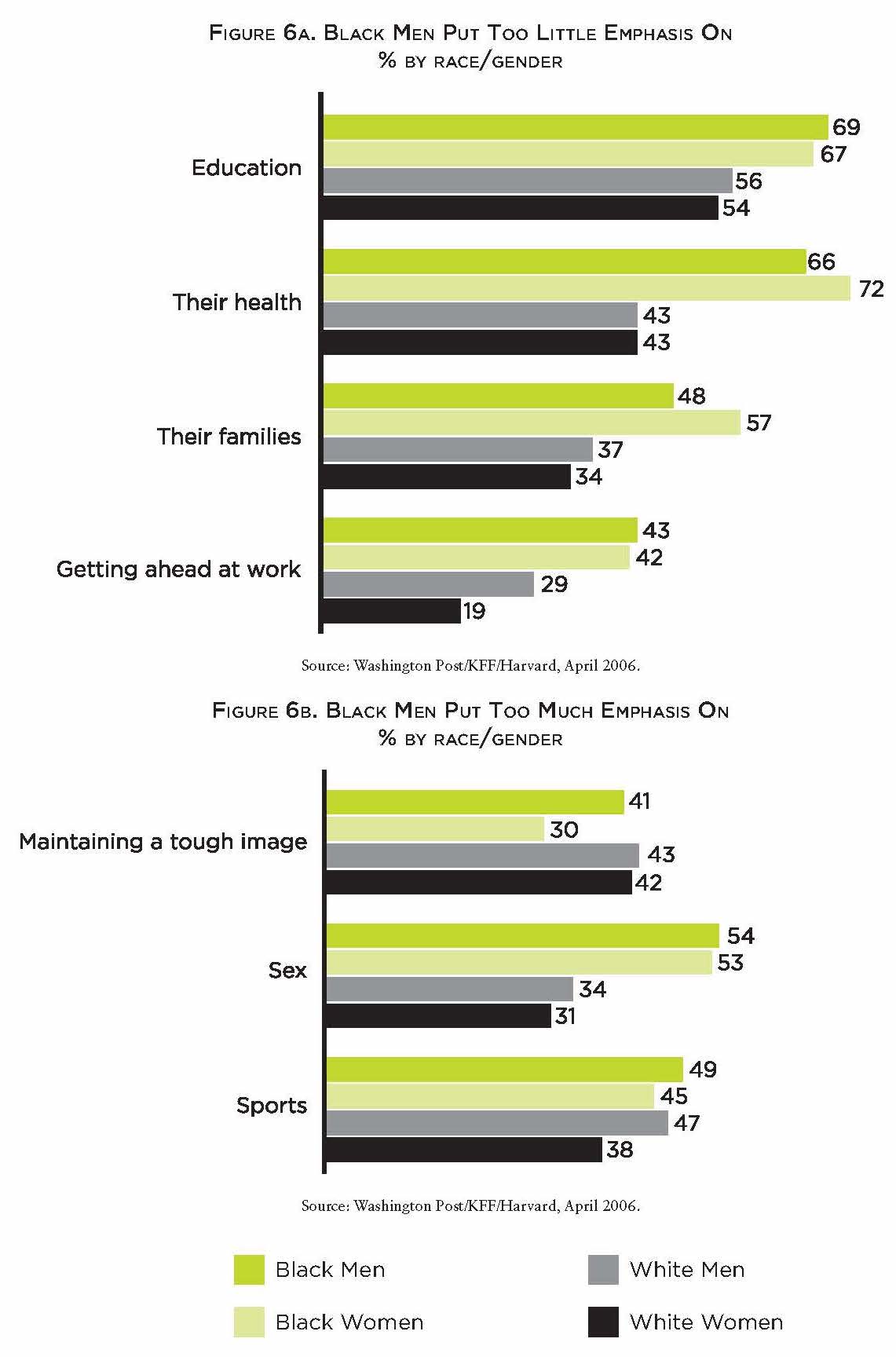

Black men are harshly critical of the priorities of black men generally, saying that black men put too little emphasis on education (69 percent), health (66 percent), their families (48 percent), and getting ahead at work (43 percent), and too much emphasis on sports (49 percent), maintaining a tough image (41 percent), and sex (54 percent) (see Figures 6a and 6b). Black men and black women tend to give far harsher ratings on these measures than white men and white women have of black men’s priorities, except the areas of maintaining a tough image and sports, where opinions converge.

Source: Washington Post/KFF/Harvard, April 2006

Though black respondents express significant worries and see a great number of problems facing black men, they still express great optimism about their future. Fully 85 percent of black respondents are optimistic about their future, compared with 72 percent of white respondents. A majority (59 percent) of black respondents say, “America’s best times are yet to come,” while a majority (53 percent) of white respondents take the alternative view, “America’s best years are behind us.” Overall, ratings on this measure have been surprisingly stable for the last 10 years, with just one noticeable shift shortly after the stock market crash at the end of 2008, with more people than ever (57 percent) saying that the “best times are yet to come.” Sixty percent of black respondents believe their child’s standard of living will be better than theirs, while just 36 percent of white respondents agree. (Washington Post/Kaiser Family Foundation/Harvard University, 2011)

Finally, according to the Pew Research Center’s 2009 report, “Racial Attitudes in America,” people may see socioeconomic status as more relevant than race when it comes to dictating shared values. Both black and white respondents see values between the races as converging, while values between classes may be diverging. Majorities of both white (70 percent) and black (60 percent) respondents say “the values held by black people and the values held by white people have become more similar.” But as black respondents consider class, a majority (53 percent) say the “values held by middle class black people and the values held by poor black people have become…more different.” Only 22 percent of black respondents say, “Middle class blacks and poor blacks have a lot in common.”