Gun Politics and Narrative Shift

Gun violence in America claims 38,000 lives every year—an average of 100 per day—and the proliferation of firearms is astronomical. It is estimated that there are 393 million guns in circulation in the United States.[1] Americans are twenty-five times more likely to be killed in a gun homicide than people in other high-income countries. For decades, the National Rifle Association (NRA) has successfully obstructed the passage of laws restricting gun ownership in any way. So successful have its efforts been that for years the NRA has been dubbed by the media as “the most powerful lobby in America,” a mantle the organization has worn with pride. Its “scorecard,” in which the NRA grades politicians from A to F depending on their responses to a candidate questionnaire, alongside the millions of dollars it spends on federal and state election campaigns, have, until recently, effectively muzzled lawmakers. This is in spite of the fact that a majority of Americans favor stricter gun laws.[2] One resulting dominant narrative has been that any politician who crosses the NRA will lose their bid for election or reelection.

The power of this narrative was on display in 2013 after the Sandy Hook tragedy in which twenty young children and six adults were murdered in their elementary school. Public support for a federal law to require universal background checks for all gun sales stood at 90 percent, but a modest bipartisan bill to that effect introduced by Senators Manchin (D-WV) and Toomey (R-PA) failed to pass after the NRA announced its opposition and sent an e-mail to all senators warning them the organization would “score” their vote; a vote in favor of the bill would negatively affect their NRA rating and lead to retaliation in their next election from an influential and united segment of their constituency: NRA members and supporters.

2013 was also a year in which there were stirrings of a new grassroots gun safety movement that would begin to challenge and disrupt the expectations around the NRA’s power and consequently the old narrative. This case study describes the ongoing shift that is taking place around one of the most controversial issues facing the country.

INTERVIEWEES

- Clark Neily, libertarian attorney behind the Heller lawsuit, Vice President for Criminal Justice, Cato Institute

- Robyn Thomas, Executive Director, Giffords Law Center

- Lori Haas, Senior Director of Advocacy, National Coalition to Stop Gun Violence

- Josh Horwitz, Executive Director, National Coalition to Stop Gun Violence

OTHER SOURCES CONSULTED:

- Chris Murphy, The Violence Inside Us: A Brief History of an Ongoing American Tragedy. Random House, 2020.

- Michael Waldman, The Second Amendment: A Biography. Simon & Schuster, 2014.

- Shannon Watts, Fight Like a Mother: How a Grassroots Movement Took on the Gun Lobby and Why Women Will Change the World. Harper One, 2019.

- Adam Winkler, Gun Fight: The Battle Over the Right to Bear Arms in America. W.W. Norton & Company, 2013.

MEDIA AND SOCAL MEDIA RESEARCH

To identify media trends, we developed a series of search terms and used the LexisNexis database, which provides access to more than 40,000 sources, including up-to-date and archived news. For social media trends we utilized the social listening tool Brandwatch, a leading social media analytics software that aggregates publicly available social media data.

BACKGROUND

The national debate over gun policy did not really begin until the 1970s. Before that, the National Rifle Association, which was founded in 1871 to promote gun safety and marksmanship among gun owners, did not actively oppose government regulation. The slogan prominently posted in 1958 on its then new headquarters in Washington, D.C., stated the organization’s mission succinctly: FIREARMS SAFETY EDUCATION, MARKSMANSHIP TRAINING, SHOOTING FOR RECREATION. But elements within the NRA began to press for a more political role after Congress passed the Gun Control Act of 1968, the first federal gun control law in 30 years. The law was passed in the wake of the assassinations of Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr., and the wave of civil disturbances that then swept the country. It banned gun shipments across state lines to anyone other than federally licensed dealers, banned gun sales to “prohibited persons” (felons, the mentally ill, substance abusers. and juveniles), and expanded the federal licensing system.

When the Gun Control Act was adopted, Franklin Orth, the executive vice president of the NRA, stood behind it. According to Orth, while certain features of the law “appear unduly restrictive and unjustified in their application to law-abiding citizens, the measure as a whole appears to be one that the sportsmen of America can live with.”[3] But some rank and file members rankled not only at the new law, but also at the very idea of gun control. Adam Winkler explains their growing opposition and hostility to the organization’s leadership:

In a time of rising crime rates, easy access to drugs, and the breakdown of the inner city, the NRA should be fighting to secure Americans the ability to defend themselves against criminals. The NRA, they thought, ‘needed to spend less time and energy on paper targets and ducks and more time blasting away at gun control legislation.’[4]

THE NRA ASCENDANT

With its new, militant leadership, the NRA’s membership tripled, its fundraising reached new heights, and its political influence increased. The organization became a prominent member of the burgeoning New Right with its contempt for “big government” in general and any gun regulation in particular. The 1972 Republican platform had supported gun control, pledging to “prevent criminal access to all weapons…with such federal law as necessary to enable the states to meet their responsibilities.” But by the time of Ronald Reagan’s presidential campaign in 1980, the platform stated, “We believe the right of citizens to keep and bear arms must be preserved. Accordingly, we oppose federal registration of firearms.” That year the NRA gave Reagan its first-ever presidential endorsement. A year later, President Reagan narrowly avoided an assassination attempt that grievously wounded his press secretary, James Brady. The shooter, John Hinckley, Jr., suffered from mental illness. He had purchased a .22-caliber revolver for $29 from a pawn shop in Texas.

The eventual passage of the Brady Bill, which President Bill Clinton signed in 1993,[5] represented a rare federal legislative defeat for the NRA, but its fortunes soon improved. In the 1994 midterms, Democrats suffered defeats in congressional races, and Bill Clinton declared it was the gun issue, more than any other, that was to blame.[6] After Republicans took control of Congress, Newt Gingrich announced, “As long as I am Speaker of this House, no gun control legislation is going to move.” From that point on, the “gun lobby,” dubbed “the most powerful lobby in D.C.,” exerted outsized control over Congress by making support of virtually any form of gun regulation a political third rail.

On April 20, 1999 Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, two 17 year olds, shot and killed twelve students and one teacher at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado before turning the guns on themselves. It was the second-worst gun massacre at a school in U.S. history and it shocked the nation. The shooters were able to buy their weapons because of a loophole in the Brady Bill that allowed “private sales” at gun shows to go forward without background checks. The NRA’s response was to go ahead with its annual meeting in nearby Denver in spite of calls for it to be relocated or postponed. On the day of the meeting, the Knight Ridder headline read, “Still grieving Colorado turns out to protest NRA meeting; Gun group remains defiant as 8,000 oppose presence in light of Columbine tragedy.” Charlton Heston, president of the NRA at the time, reassured his supporters, saying, “Each horrible act can’t become an ax for opportunists to cleave the very Bill of Rights that binds us.” The GUNS DON’T KILL PEOPLE; PEOPLE KILL PEOPLE bumper sticker made its appearance, and the NRA continued to oppose legislation to close the private sale loophole.

During the post-Columbine period, the NRA’s power and influence continued to grow, not wane. President Clinton, who was in the throes of his own impeachment proceedings, pushed to close the Brady Bill loophole by requiring universal background checks, but the NRA’s congressional allies killed the bill. The organization was bigger and richer than ever. Flush with membership contributions and large donations from the firearms industry, with active and vocal chapters in all 50 states and with a solid core of single-issue voters, the narrative promoted by the NRA that it was “the nation’s most powerful lobby” was carried by the media and reinforced each time a candidate with a poor NRA rating lost an election.

By the year 2000, the NRA’s political influence was undeniable, and it turned its sights to defeating Al Gore, the Democratic candidate for president. The organization spent millions on behalf of George W. Bush and Republican candidates in Senate races. In a leaked video circulated during the campaign, a high-ranking NRA official claimed, “If we win, we’ll have a president where we work out of their office—unbelievably friendly relations.” At the NRA’s 2000 annual meeting, Charlton Heston, who was to become its president, gave a legendary speech whose soaring rhetoric summed up the gun lobby’s philosophy:

Sacred stuff resides in that wooden stock and blue steel, something that gives the most common man the most uncommon of freedoms…when ordinary hands can possess such an extraordinary instrument that symbolizes the full measure of human dignity and liberty. As we set out this year to defeat the divisive forces that would take freedom away, I want to say those fighting words for everyone within the sound of my voice to hear and to heed—and especially for you, Mr. Gore.

He then held up a replica of a colonial rifle and exclaimed, “From my cold, dead hands!”

The NRA’s political power was solidified during the first decade of the new millennium. Early in his first administration George W. Bush signed a law providing broad immunity from lawsuits for gun manufacturers and sellers, and the NRA’s coffers increased with funding from the industry. Republican candidates came to rely more and more on gun lobby contributions; in the year 2000, the NRA contributed close to $3 million to Republican campaigns, representing 92 percent of its total contributions.[7] In 2004, the assault weapons ban, originally passed in 1994, was allowed to expire. At the state level, the NRA successfully blocked the passage of gun control measures and campaigned for and won state constitutional protections for gun owners. By the mid-2000s, all but six states guaranteed a right to bear arms as a matter of state constitutional law, and nearly all of those explicitly protected an individual right. The stage was now set for a reckoning on the meaning of the Second Amendment.

For 200 years the Second Amendment of the Constitution was virtually invisible. It had come to be known as the “lost amendment” because it was almost never written about or cited by scholars and legal practitioners. Although for decades the NRA had invoked the individual right to bear arms, that concept was not supported by constitutional scholars or by the courts. Rather, the prevailing view was that the Amendment protected the “collective right” of the states to maintain their own militia, like the National Guard.

In the early 1990s the NRA funded a new group, Academics for the Second Amendment, and launched an annual “Stand Up for the Second Amendment” essay contest with a $25,000 cash prize. These efforts bore fruit. During the 1990s, eighty-seven law review articles were published and a majority of fifty-eight adopted the individual-rights position. The dial was moving; the NRA’s interpretation of the amendment was gaining ground in academic circles. In 2001, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit (in Louisiana) became the first federal appeals court to adopt the individual-rights view.[8] By the mid-2000s two lawyers from the libertarian Institute for Justice[9] decided that the time was right to challenge the most restrictive gun law in the country on Second Amendment grounds.

The Firearms Control Regulations Act of 1975 was passed by the District of Columbia City Council in 1976. The law banned residents from owning handguns, automatic firearms, or high-capacity semi-automatic firearms and prohibited possession of unregistered firearms. The law also required firearms kept in the home to be “unloaded, disassembled, or bound by a trigger lock or similar device,” essentially a prohibition on the use of firearms for self-defense in the home. A challenge to the law, orchestrated by Institute for Justice lawyers Clark Neily and Steve Simpson, began to wend its way through the courts and was accepted for review by the Supreme Court in its 2008 term.[10] On June 26, 2008, the Court announced its ruling in District of Columbia v. Heller. In a 5-4 majority opinion authored by Justice Scalia, the Court held that the Second Amendment protects an individual’s right to keep and bear arms, unconnected with service in a militia, for traditionally lawful purposes, such as self-defense within the home, and that the D.C. law was therefore unconstitutional.

Although the Court’s opinion acknowledged that, “[l]ike most rights, the right secured by the Second Amendment is not unlimited” and warned that “[n]othing in our opinion should be taken to cast doubt on longstanding prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill, or laws forbidding the carrying of firearms in sensitive places such as schools and government buildings, or laws imposing conditions and qualifications on the commercial sale of arms,” the gun lobby and its supporters in Congress declared total victory, further strengthening the narrative that the NRA was in control of the gun debate. Over and over again, they invoked “freedom” as the core value protected by the decision:

This is a great moment in American history. It vindicates individual Americans all over this country who have always known that this is their freedom worth protecting.

The Court made the right decision today because federal, state and local governments should not be able to arbitrarily take away freedoms that are reserved for the people by our Constitution.

Today the Supreme Court ruled in favor of freedom and democracy by overturning this unlawful ban.

As we in Congress consider new legislation, we could take a lesson from the Supreme Court today by ensuring that the freedoms granted in the Constitution are a guiding light to the formation of our nation’s legislation.

Following the Columbine massacre, mass shootings occurred in the United States at a steady pace. The year 2007 was an especially deadly year, with four separate incidents including the Virginia Tech mass shooting that left thirty-two people dead.[11] Nevertheless, the NRA’s influence did not wane. In April 2009, a year after the Supreme Court’s Second Amendment decision and one year into the first Obama Administration, in an article entitled “The Public Takes Conservative Turn on Gun Control,” the Pew Research Center reported that:

For the first time in a Pew Research survey, nearly as many people believe it is more important to protect the right of Americans to own guns (45%) than to control gun ownership (49%). As recently as a year ago, 58% said it was more important to control gun ownership while 37% said it was more important to protect the right to own guns.[12]

By the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century, a total of 166 men, women, and children had perished in mass shootings. But while those incidents received the most media coverage, they represented and still represent a tiny fraction of the incidents of gun violence in the country. In 2010, for example, there were 31,672 deaths in the United States from firearm injuries, mainly through suicide (19,392) and homicide (11,078), according to Centers for Disease Control compilation of data from death certificates. The remaining firearm deaths were attributed to accidents, shootings by police, and unknown causes.

Guns were, and still are, by far the most common means of suicide, and the majority of intimate partner homicides are with guns. The number of firearm deaths has increased every year since 2000 and is especially dire in low wealth communities of color. Black Americans are disproportionately impacted by gun violence. They experience nearly 10 times the gun homicides, 15 times the gun assaults, and 3 times the fatal police shootings as white Americans. Black men make up 52% of all gun homicide victims in the United States, despite comprising less than 7% of the population.

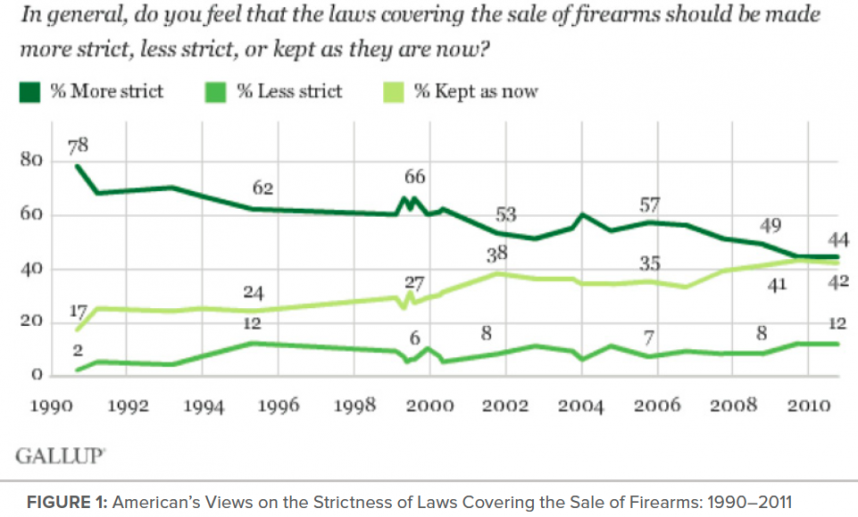

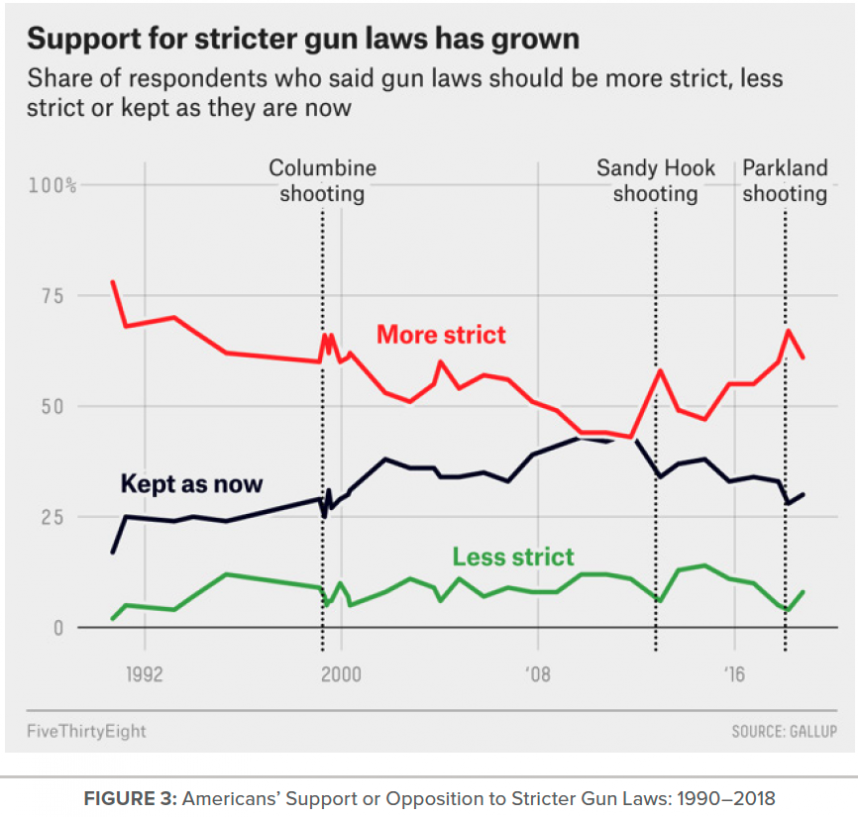

But in spite of these damning statistics, as 2008 rolled into 2009 the NRA was at the pinnacle of its power, and the public’s support for stricter gun laws was at its lowest ebb in 20 years. According to the Gallup Poll, in 1991, 78 percent of the public felt that “the laws covering the sale of firearms should be made more strict.” By 2009 support for stricter laws had dropped to 49 percent and dropped another five points by 2010. At the same time, the NRA was receiving millions of dollars from arms manufacturers including Smith & Wesson, the Beretta Group, and Browning.[13] During his 2008 presidential campaign, Barack Obama released an approving statement when the Supreme Court announced its Second Amendment decision, and he did not campaign on the gun control issue. During his first term in office, Obama did not push for any gun control measures despite the continuing carnage: mass shooting at Fort Hood, Texas (thirteen dead); a mass shooting at an Aurora, Colorado movie theater (twelve dead); and the Tucson, Arizona shooting that left six dead and grievously injured Congresswoman Gabby Giffords. During the run up to the 2010 midterm elections, Republican and Democratic candidates alike sought donations and approval ratings from the NRA and openly opposed gun control measures. When the Republicans won back the House, the writing was on the wall: no restrictions on gun ownership were going to pass on their watch.

SANDY HOOK AND THE STIRRINGS OF A GRASSROOTS GUN SAFETY MOVEMENT

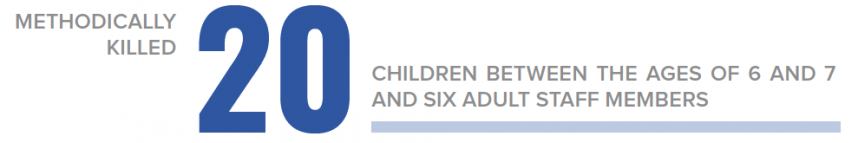

On December 14, 2012 20-year-old Adam Lanza shot his way into the Sandy Hook Elementary School in Fairfield County, Connecticut armed with a Bushmaster XM15-E2S rifle and ten magazines with thirty rounds each. He forced his way into two first grade classrooms and methodically killed twenty children between the ages of 6 and 7 and six adult staff members. Earlier that day he had shot and killed his mother, and after the school massacre, he shot and killed himself. The nation reacted in horror, and the tragedy ushered in a period of soul searching during which the “thoughts and prayers” traditionally offered up by political leaders were soundly rejected as inadequate by a grieving community.

President Barack Obama gave a televised address on the day of the shootings and said, “We’re going to have to come together and take meaningful action to prevent more tragedies like this, regardless of the politics” (emphasis added). The NRA stayed silent for a week; then, on December 21, Executive Vice President Wayne LaPierre issued a statement calling on Congress “to act immediately to appropriate whatever is necessary to put armed police officers in every single school in this nation,” claiming that gun-free school zones attracted killers and that another gun ban would not protect Americans.

The Sandy Hook tragedy proved to be a watershed moment. In the words of Senator Chris Murphy (D-CT), a passionate advocate for gun safety, “there was reason to believe that Sandy Hook, by itself, had fundamentally changed the politics of gun violence.”[14] On the morning of the shooting, in Zionsville, Indiana, Shannon Watts, a mother of five with a background in public relations, stood before her TV “transfixed by the live footage of children being marched out of their school into the woods for safety.” In her 2019 book, Fight Like a Mother, Watts expresses what millions of Americans were feeling that day:

I actually said out loud, ‘Why does this keep happening?’…. In my head, I heard only one word in response to my question, and that word was Enough. Enough waiting for legislators to pass better gun laws. Enough hoping that things would somehow get better. Enough swallowing my frustration when politicians offered their thoughts and prayers but no action. Enough listening to the talking heads on the news channels calling for more guns and fewer laws. Enough complacency. Enough standing on the sidelines.

That night, Watts created a new Facebook page called One Million Moms for Gun Control and the “likes” began pouring in.[15] “Women everywhere were asking how they could join my organization, and I didn’t even realize I’d started one,” she writes. Soon renamed Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America, its message spread rapidly on social media, and a reinvigorated grassroots movement began to take hold.

Sandy Hook also birthed another organization that was to become a major force in the gun safety movement. Congresswoman Gabby Giffords, still undergoing rehabilitation 2 years after she was shot in the head outside a Tucson supermarket, and her husband, NASA astronaut Captain Mark Kelly, now a U.S. senator, were moved to action. In 2013 they founded the organization now known as Giffords. Its mission statement boldly and explicitly took on the powerful gun lobby:

Giffords is fighting to end the gun lobby’s stranglehold on our political system. We’re daring to dream what a future free from gun violence looks like. We’re going to end this crisis, and we’re going to do it together.

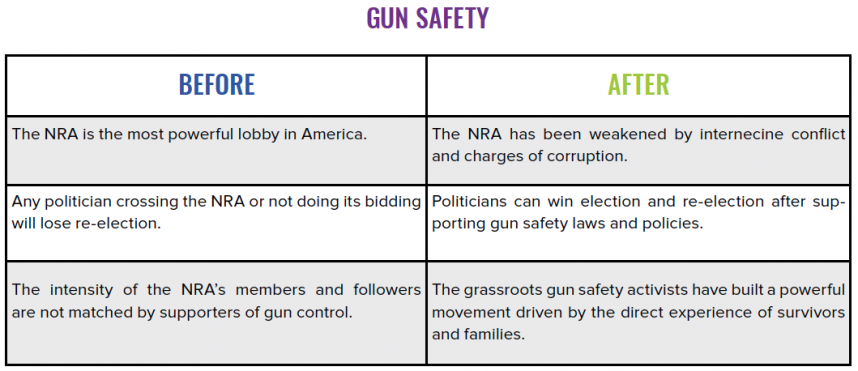

Giffords and Moms Demand Action joined the established gun control organizations—including Brady[16], the National Coalition to Stop Gun Violence[17], and Mayors Against Illegal Guns[18]—to breathe new life into the movement. And they understood that above all, they had to challenge the narrative that for years had been a barrier to the passage of any gun safety laws: The NRA is the most powerful lobby in the nation, and any politician crossing it or not doing its bidding will be punished.

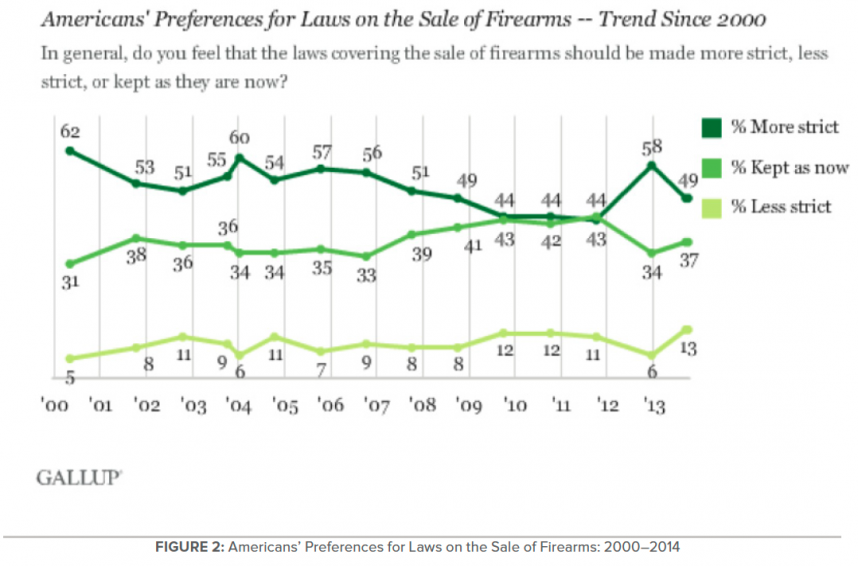

In the immediate aftermath of Sandy Hook, public support for stricter laws covering the sale of firearms shot up to 58 percent, and nine out of ten Americans supported universal background checks. But in spite of public opinion and the demands of the bereaved parents that something had to be done, the effort to close the Brady loophole, a relatively modest goal that would require background checks for gun show and internet sales, still could not command a majority of votes in Congress. As mentioned earlier, a bipartisan bill introduced by Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) and Pat Toomey (R-PA) failed to pass in April 2013 after the NRA announced its opposition and sent an e-mail to all senators warning them the organization would “score” their vote, meaning it would factor into the NRA’s election-year grading system.

The bill failed by only six votes, but gun safety activists realized they needed a new strategy. “After that tough loss, we turned our focus to making challenges at the state level,” said Shannon Watts. Given the federal government’s inaction, several states had already begun to pass significant reforms to rein in gun violence. That year the governors of Connecticut, Delaware, and Maryland signed new gun safety laws, and two out of three of them were re-elected (the third, Martin O’Malley of Maryland, was term-limited).

GUN POLITICS IN TRANSITION

The Manchin-Toomey debacle may have seemed like an NRA victory, but it actually signaled the beginning of a historic realignment in gun politics. The gun rights movement’s political influence had long been attributed to the “intensity gap.” The NRA’s members were not that numerous—it had about 5 million dues-paying members—but what the organization lacked in numbers it made up for in intensity. Its members were highly motivated single-issue voters who could be mobilized rapidly to respond to calls to action. According to Robyn Thomas of the Giffords Law Center:

I’ve been showing up at hearings for a long, long time. For many years it was me and the gun rights activists. They show up in droves to every hearing, big or small. I could testify at a small city council or at a federal congressional hearing and in both cases, it was rooms filled with gun rights activists and no one on our side.

The fate of Machin-Toomey demonstrated how damaging the intensity gap was to any meaningful policy change. Ladd Everitt, then Communications Director for the National Coalition to Stop Gun Violence, lamented:

We’ve always been too polite, by appealing to politicians to do the right thing…appealing to their conscience and hoping they’d come around even when the evidence suggested they wouldn’t. We went too far into the realm of educating the public and ceded the field of politics to the NRA.

While plenty of people support stricter gun laws, few advocated for them or were motivated enough by them to change their voting behavior unless they were personally affected. In the face of overwhelming but passive public support for universal background checks—90 percent favored universal background checks as did 75 percent of NRA members—the gun lobby prevailed. But the status quo was about to be disrupted. Josh Horwitz, Executive Director of the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence, describes the intense public response to Congress’s failure to act:

It wasn’t just the Sandy Hook shooting itself. It was the absolute horror when the Senate did nothing about it. But what happened was people were so appalled that they joined and donated to the movement. They became involved, and our movement became so much bigger and so much stronger as a result.

Moms Demand Action scored some early victories that demonstrated the savvy and potential power of a grassroots movement that united women (and men) from all over the country—north, south, east and west, rural, suburban, and urban. Social media was key to the movement’s success. Within months of its first appearance on Facebook it had attracted tens of thousands of supporters. “Stroller jams” became a popular tactic. Moms would show up for legislative hearings with their babies and toddlers in strollers and, “as a result, lawmakers didn’t have any room to maneuver past us; they had to stop and talk to us.”[19] Activists targeted companies that allowed open carry on their premises.[20] Their campaign “Skip Starbucks Saturday” went viral and forced Starbucks to change its policy and ban all guns from its stores. The organization became adept at using social media to encourage corporate responsibility. Using the hashtag #EndFacebookGunShows, it generated enough support to compel Facebook to announce a series of new policies around gun sales, including deleting posts offering guns for sale without a background check. Its #OffTarget petition garnered nearly 400,000 signatures and soon Target announced:

Starting today we will respectfully request that guests not bring firearms to Target—even in communities where it is permitted by law…. This is a complicated issue, but it boils down to a simple belief: Bringing firearms to Target creates an environment that is at odds with the family-friendly shopping and work experience we strive to create.

These examples of corporate responsibility generated a buzz in both traditional and online media. There were instances of counter-demonstrations by open carry activists who showed up en masse at stores and restaurants carrying guns and rifles. These incidents brought more media attention to the open carry debate and more opportunities for gun safety activists to broadcast their message. Shannon Watts describes how Moms Demand Action exploited these incidents to bring in new members and force companies to change their policies:

The first such event happened at a Jack in the Box in the Dallas-Ft. Worth area when members of a gun extremist group called Open Carry Texas walked into the restaurant carrying long guns. The employees were so scared that they locked themselves inside a walk-in freezer. We issued a press release, launched an online petition, and tweeted photos, with the hashtag #JackedUp, of our members eating at other fast-food restaurants that had safer gun policies. Within days the company announced it would begin enforcing its policy of no guns inside its restaurants. After that, there were similar incidents at Chipotle, Chili’s and Sonic-Drive-In.[21]

On April 16, 2014 the outgoing mayor of New York City and media mogul Michael Bloomberg announced what The New York Times dubbed “A $50 million Challenge to the N.R.A.” —the founding of a new organization called Everytown for Gun Safety. It would bring the two groups Bloomberg already funded, Mayors Against Illegal Guns and Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America, under one umbrella. Bloomberg’s rhetoric made it clear the gloves were off:

They say, ‘We don’t care. We’re going to go after you. If you don’t vote with us we’re going to go after your kids and your grandkids and your great-grandkids. And we’re never going to stop.’ We’ve got to make them afraid of us. (NEW YORK TIMES)

Everytown’s message was simple and straightforward: common-sense gun policies supported by a huge majority of Americans can save lives. Everytown’s goal was to be the NRA’s counterweight. It would back candidates who supported gun safety laws and oppose those who did not. It would mobilize its members to gather en masse at legislative hearings and when votes were taken. It would mount campaigns to compel corporations to exercise responsibility when it came to gun safety. In the words of one journalist, “A bigger, richer, meaner gun-control movement has arrived.”[22] And with its achievements, it would shift the narrative that had impeded progress for so many years and show that the NRA was no longer the most powerful lobby, the voters want action, and voting for “gun sense” laws was a win-win—lives would be saved and backers would win elections.

In its first year, Everytown for Gun Safety was instrumental in passing laws in eight states to keep guns out of the hands of domestic abusers—laws that in the past had been vigorously resisted by the NRA.[23]

As the gun safety movement continued to grow, the country continued to experience the terrible carnage of mass shootings and the death tolls would reach new heights. In June 2015, Dylann Roof, a white supremacist, would murder nine African American worshippers in Charleston, South Carolina. One year later, forty-nine people were killed in the Pulse Nightclub massacre, a gay bar and performance space in Orlando, Florida, in a homophobic attack. In October 2017 in the deadliest mass shooting by a lone shooter in U.S. history, fifty-eight people died at a Las Vegas country music festival. And then came Parkland. On February 14, 2018, Nikolas Cruz, a former student, opened fire with a semi-automatic rifle at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, killing seventeen people and injuring seventeen others.

The reaction to the Parkland shooting was intense and global. Surviving students took to social media and within hours created a cascade of demands for lawmakers to act. Three days after the shooting, a 17-year-old senior named Emma Gonzalez electrified the world with her speech at a gun control rally in Fort Lauderdale:

The people in the government who were voted into power are lying to us. And us kids seem to be the only ones who notice and our parents to call BS. Companies trying to make caricatures of the teenagers these days, saying that all we are self-involved and trend-obsessed and they hush us into submission when our message doesn’t reach the ears of the nation, we are prepared to call BS. Politicians who sit in their gilded House and Senate seats funded by the NRA telling us nothing could have been done to prevent this, we call BS. They say tougher gun laws do not decrease gun violence. We call BS. They say a good guy with a gun stops a bad guy with a gun. We call BS. They say guns are just tools like knives and are as dangerous as cars. We call BS. They say no laws could have prevented the hundreds of senseless tragedies that have occurred. We call BS. That us kids don’t know what we’re talking about, that we’re too young to understand how the government works. We call BS. If you agree, register to vote. Contact your local congresspeople. Give them a piece of your mind!

Days later, Everytown for Gun Safety launched a new campaign called Students Demand Action—End Gun Violence in America, to be led by student activists. Weeks later, Governor Rick Scott (R-FL) signed into law restrictions on firearm purchases and the possession of “bump stocks” in what was reported as “the most aggressive action on gun control taken in the state in decades and the first time Mr. Scott, who had an A-plus rating from the National Rifle Association, had broken so significantly from the group.” On March 24, the organization formed by Gonzalez and other Marjory Stoneman Douglas survivors, Never Again MSD, held The March for Our Lives, a massive protest in Washington, D.C. attended by more than half a million people. Close to 900 sibling events were held across the United States and around the world. A national survey taken 4 days after the shooting showed virtually universal support for background checks (97 percent in favor) and strong majority support for a ban on assault weapons and a mandatory waiting period for all gun purchases.

The March for Our Lives was the largest student-led demonstration since the Vietnam War, and it included many thousands of youth of color from cities beset by gun violence. The student leaders’ commitment to diversity in their organizing work is a long overdue correction to what has been the country’s past racialized attention to the gun violence epidemic. Until recently, movements to end gun violence of long standing in communities of color have been ignored while mass shootings of mostly white people have garnered enormous public attention.

Soon after the Parkland shooting, the Peace Warriors, a group of Black high school students from Chicago who have been fighting gun violence for years without receiving much attention from the outside world, flew to Florida to meet with the Marjory Stoneman Douglas activists. Over the course of several days, young people from one of the safest cities met and got to know young people from a city beset by gun violence and learned from one another. “We found our voice in Parkland,” said Arieyanna Williams, a 17-year-old Peace Warriors member. “We felt like we weren’t alone in this situation and we finally can use our voices on a bigger scale.” Marjory Stoneman Douglas student Sarah Chadwick said, “White privilege does exist and a lot of us have it. If we could use our white privilege to amplify the voices of minorities, then we’re going to use it. The more we ignore it, the worse it gets.”[24]

The NRA waited a week before making any pronouncements on the Parkland shooting. But in his address before the Conservative Political Action Conference, Wayne LaPierre repeated his post-Sandy Hook talking point that “the only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun” and echoed President Trump’s tweet calling for arming the teachers. But the NRA was on the defensive. A Business Insider article titled, “Something historic is happening with how Americans see the NRA” reported that polls following Parkland showed that “[f]or the first time in nearly two decades, Americans have turned against the National Rifle Association” and that “significantly more Americans express a negative opinion of the National Rifle Association than a positive one.”

The mid-term elections of 2018 showed the impact of the new narrative—going against the NRA did not mean certain defeat at the polls. With support from both the Giffords PAC and Everytown for Gun Safety,[25] gun control advocates picked up at least seventeen seats in the House by defeating incumbents backed by the NRA. Many of the victors were women. One of them was Lucy McBath, an African American leader of Moms Demand Action whose 17-year-old son was fatally shot in 2012 and who made gun violence the centerpiece of her campaign to represent a Georgia district once held by Newt Gingrich. In a tweet celebrating her victory, McBath wrote, “Absolutely nothing—no politician & no special interest—is more powerful than a mother on a mission.” Another winner was Arizona’s Ann Kirkpatrick, who had been a staunch NRA defender and boasted an A rating from the organization, but in 2018 she won the Democratic primary on the promise to ban assault weapons and enact universal background checks. “I’ve changed my mind,” she explained.

By spring 2019, another shift in the narrative was taking place as an attempted coup erupted at the NRA’s annual meeting in Indianapolis. In an article titled, “Insurgents Seek to Oust Wayne LaPierre in N.R.A. Power Struggle,” The New York Times reported:

Turmoil racking the National Rifle Association is threatening to turn the group’s annual convention into outright civil war, as insurgents maneuver to oust Wayne LaPierre, the foremost voice of the American gun rights movement. The confrontation pits Mr. LaPierre, the organization’s longtime chief executive, against its recently installed president, Oliver L. North, the central figure in the Reagan-era Iran-contra affair, who remains a hero to many on the right.

La Pierre eventually beat back the attack and North and his supporters were forced to resign, but media coverage from that point on dwelled on the severe problems the NRA was facing, from a serious decline in revenue to the launch of an investigation by the New York State Attorney General, Leticia James, into its finances and tax-exempt status. Headlines described an organization riven by scandal and division.

- “Major donors fire back against NRA; Turmoil has some keeping their cash while others sue,” Chicago Tribune, November 22, 2019

- “Could turmoil at NRA be a game changer?” USA Today, August 9, 2019

- “Turmoil persists as NRA sidelines its top lobbyist,” The Washington Post, June 21, 2019

- “NRA beset by infighting over whether it has strayed too far,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 25, 2019

On September 12, 2019 presidential hopeful Beto O’Rourke stole the show during that evening’s Democratic presidential primary debate when, in response to a direct question from the moderator about his gun control plan, he said, “Hell yeah, we’re going to take your AR-15! If it’s a weapon that was designed to kill people on the battlefield, we’re going to buy it back.” This was only one month after forty-six people were gunned down at a Walmart in his hometown of El Paso. Twenty-three died and twenty-three were injured. Most of the Democratic contenders had already announced their support for more gun restrictions by that point in the primary process, leading a Senior Politics writer from USNews.com to observe, “Democrats Are No Longer Gun Shy.”

SPOTLIGHT ON VIRGINIA

Virginia has long been considered a “gun friendly” state and a fitting home for the NRA’s national headquarters. But over the past decade, gun politics in the Commonwealth has undergone a 180-degree turn, and narrative shift, propelled by an expanding gun safety movement, has played a dominant role. As a result, Virginia went from being a state with virtually no restrictions on gun ownership to being the harbinger of a new gun safety sensibility in America. In April 2020, Governor Ralph Northam signed a package of five gun control measures into law—all of them priorities of the gun violence prevention movement:

Universal background checks for all gun sales in Virginia;

- A one-per-month limit on the purchase of handguns;

- A requirement for the loss or theft of a firearm to be reported within 48 hours (with a civil penalty of up to $250 for failure to report);

- An increase in penalties for reckless storage of loaded and unsecured firearms in a way that endangers children younger than 14 years of age;

- A “red flag” bill, which provides for a procedure for the temporary removal of guns from people at high risk of self-harm or harm to others.[26]

Governor Northam’s quote in the official press release acknowledged the role played by the advocacy community and echoed its message: “We lose too many Virginians to gun violence, and it is past time we took bold, meaningful action to make our communities safer. I was proud to work with legislators and advocates on these measures, and I am proud to sign them into law. These commonsense laws will save lives.”

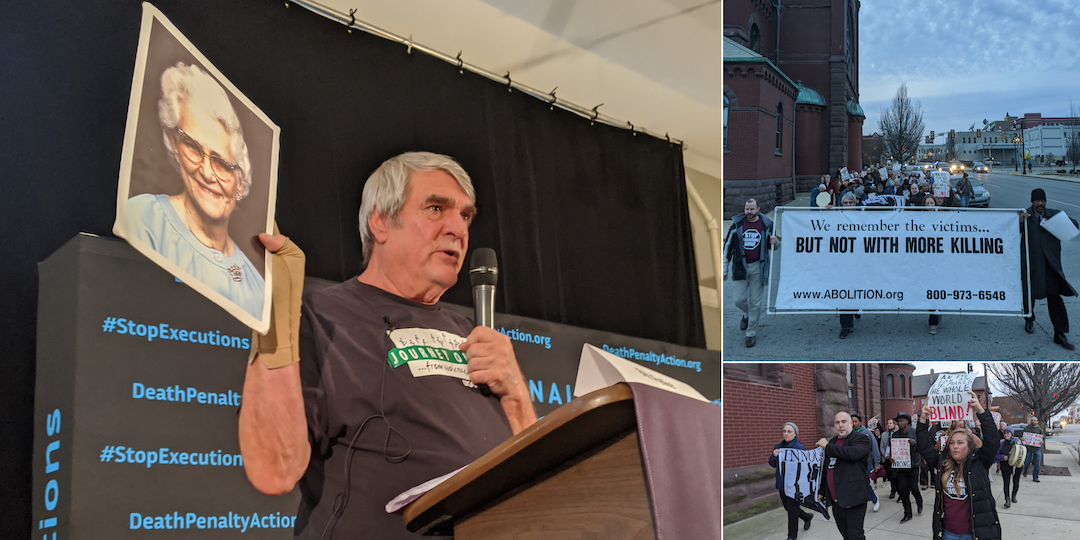

This outcome was more than a decade in the making and was largely the result of organizing spearheaded by families impacted by the 2007 Virginia Tech mass shooting in which thirty-two students, professors, and administrators were killed and seventeen others were wounded. Lori Haas of Richmond, whose daughter Emily is a Virginia Tech survivor, recalls that “after coming out of the fog” of the disaster, she and others started trying to figure out “what went wrong. We started asking questions and speaking up, and then we got it: We don’t have any laws! The shooter didn’t have to have a background check. Nobody’s watching. Nobody’s paying attention.” Haas became a volunteer with the Virginia Center for Public Safety[27] and in 2009 became the Senior Director of Advocacy for the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence. Her first several years as a gun violence prevention (GVP) advocate in Virginia were frustrating. The Republican Party controlled the Senate, the House of Delegates, and the governorship, and the gun lobby held sway. Not only were GVP advocates unable to get a meaningful hearing of their proposals, but also the gun lobby succeeded in passing a bill allowing concealed carry permit holders to carry their weapons into restaurants and bars. But the mood among voters was changing. Haas explains:

We began to be joined in our testimony by others who are affected by gun violence. People were willing to step up and talk about the awful shootings that occur throughout the Commonwealth in too many places. During that time our numbers were growing. We were going out across the Commonwealth speaking at every place we could: faith groups, book clubs, city councils, to ordinary everyday citizens. People would raise their hands and say, ‘will you come and talk to us in Charlottesville or in Roanoke or in Hampton Roads or Northern Virginia?’ The interest was growing by leaps and bounds and people kept asking, ‘Why can’t we get it done? Background checks are so simple. It’s such a low bar.’ And we would respond, ‘Let your voices be heard. And if you can’t change your representatives’ minds, you have to change their seats.’

This outcome was more than a decade in the making and was largely the result of organizing spearheaded by families impacted by the 2007 Virginia Tech mass shooting in which thirty-two students, professors, and administrators were killed and seventeen others were wounded. Lori Haas of Richmond, whose daughter Emily is a Virginia Tech survivor, recalls that “after coming out of the fog” of the disaster, she and others started trying to figure out “what went wrong. We started asking questions and speaking up, and then we got it: We don’t have any laws! The shooter didn’t have to have a background check. Nobody’s watching. Nobody’s paying attention.” Haas became a volunteer with the Virginia Center for Public Safety[27] and in 2009 became the Senior Director of Advocacy for the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence. Her first several years as a gun violence prevention (GVP) advocate in Virginia were frustrating. The Republican Party controlled the Senate, the House of Delegates, and the governorship, and the gun lobby held sway. Not only were GVP advocates unable to get a meaningful hearing of their proposals, but also the gun lobby succeeded in passing a bill allowing concealed carry permit holders to carry their weapons into restaurants and bars. But the mood among voters was changing. Haas explains:

We began to be joined in our testimony by others who are affected by gun violence. People were willing to step up and talk about the awful shootings that occur throughout the Commonwealth in too many places. During that time our numbers were growing. We were going out across the Commonwealth speaking at every place we could: faith groups, book clubs, city councils, to ordinary everyday citizens. People would raise their hands and say, ‘will you come and talk to us in Charlottesville or in Roanoke or in Hampton Roads or Northern Virginia?’ The interest was growing by leaps and bounds and people kept asking, ‘Why can’t we get it done? Background checks are so simple. It’s such a low bar.’ And we would respond, ‘Let your voices be heard. And if you can’t change your representatives’ minds, you have to change their seats.’

The turning point came in 2013. By then polls were running in favor of more restrictions. A survey conducted by Lake Research Partners in two districts in southwestern Virginia, considered the most pro-gun districts in the state, showed that an overwhelming 94 percent of gun owners favored universal background checks and more than 70 percent of voters opposed guns on campuses.[28] All three Democrats running for statewide office that year made gun safety a prominent issue in their campaigns. In their gubernatorial debate, candidate Ken Cuccinelli (R) declared, “I’m running against the only F-rated candidate from the NRA,” to which candidate Terry McAuliffe (D) responded:

Now whatever rating I may get from the NRA, I’m gonna stand here and tell you today that as governor, I want to make sure that every one of our citizens in the Commonwealth of Virginia are safe. Every one of our children, when they go into a classroom, should know that they are safe. When any one of our loved ones goes into work…. We need to eliminate guns from the folks who should not own guns.

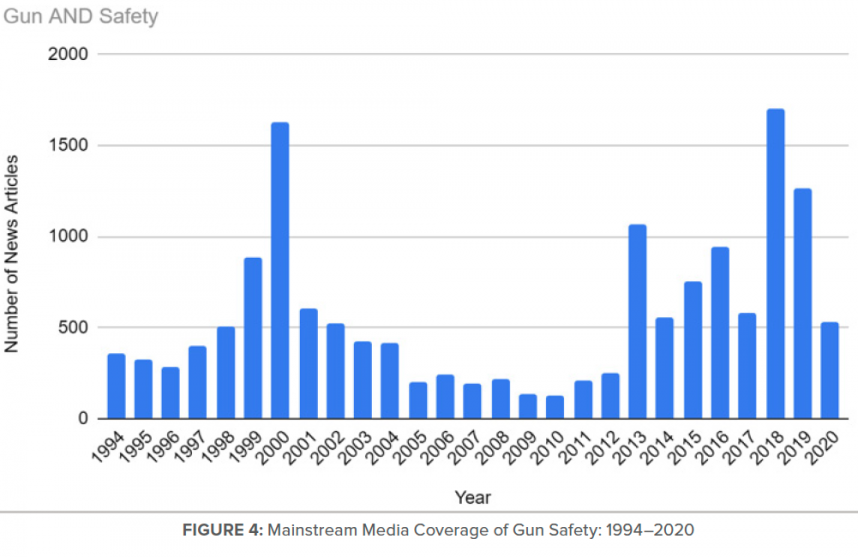

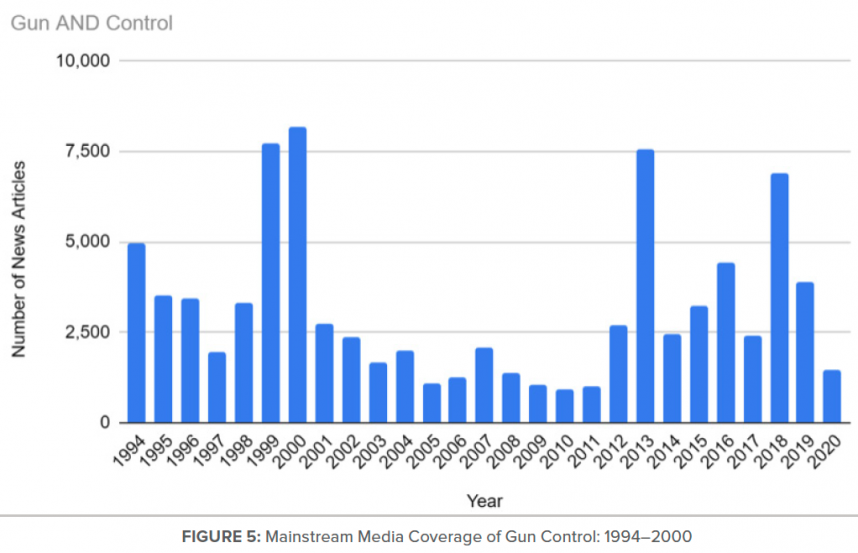

This turning point is seen in a dramatic increase in media coverage of gun violence in 2013. Between 1994 and 2020, roughly 85,600 news media articles were published in mainstream outlets in the United States referring to “gun control,” while another 15,300 articles were published with specific reference to “gun safety.” As seen in Figures 4 and 5, 1999–2000 saw a significant increase in media engagement with the topics of gun control and safety. This was followed by a decline in engagement, which remained stable until another major spike in coverage in 2013. Between 2012 and 2013, references to “gun control” nearly tripled (increasing from roughly 2,700 articles in 2012 to more than 7,500 articles in 2013), while references to “gun safety” more than quadrupled in sampled articles (increasing from 248 articles in 2012 to more than 1,060 articles in 2013).

Alongside the increase in mainstream news media focus, a growing number of politicians became willing to speak out against the status quo. Ralph Northam, who was running for lieutenant governor at the time, was outspoken about his opposition to the gun lobby, and Mark Herring’s first political ad after winning the nomination for attorney general highlighted the responsibility of leaders “to protect our families from gun violence.” All three won their elections.

Despite the success that gun violence prevention groups enjoyed in the 2013 elections, however, efforts to strengthen gun laws in the state legislature remained stalled. The Virginia legislature even failed to act on legislation to keep guns out of the hands of domestic abusers—a law that passed with broad bipartisan support in a number of other states—despite its successful passage in the state Senate in 2014 after a 29-6 vote. Sen. Adam P. Ebbin (D-Alexandria) put forward a measure to make allowing a child 4 years old or younger to use a firearm a misdemeanor, saying, “I hope we can all agree that toddlers should not be allowed to play with a gun.” But the NRA lobbyist countered that the bill “would impose an arbitrary minimum age at which a person would be allowed to receive firearms training,” and the bill failed.[29]

The 2017 gubernatorial election between Democrat Ralph Northam and Republican Ed Gillespie amounted to a state referendum on guns, with Michael Bloomberg and the Everytown for Gun Safety Action Fund contributing close to $2 million to elect Northam and his two running mates, Mark Herring for attorney general and Justin Fairfax for lieutenant governor. In the midst of the campaign, a shooter fired 1,000 rounds of ammunition on the crowd attending a music festival in Las Vegas, killing sixty people and wounding more than 400. A New York Times article was published several days later with the headline, “In Virginia, Gun Control Heats Up the Governor’s Race,” and the candidate’s dueling responses captured the partisan divide on the issue. Northam argued, “We as a society need to stand up and say it is time to take action. It’s time to stop talking.” Gillespie, who touted his “A” rating from the NRA, said it was “too early to discuss policy responses to gun violence.” In November Northam defeated Gillespie, winning by the largest margin for a Democrat in more than 30 years. On taking office in January 2018 Gov. Northam introduced several gun safety measures, but they failed in the Republican-controlled General Assembly. Then, on May 31, the Virginia Beach mass shooting happened, in which twelve people were killed at the city’s municipal center by a heavily armed lone gunman.

The 2017 gubernatorial election between Democrat Ralph Northam and Republican Ed Gillespie amounted to a state referendum on guns, with Michael Bloomberg and the Everytown for Gun Safety Action Fund contributing close to $2 million to elect Northam and his two running mates, Mark Herring for attorney general and Justin Fairfax for lieutenant governor. In the midst of the campaign, a shooter fired 1,000 rounds of ammunition on the crowd attending a music festival in Las Vegas, killing sixty people and wounding more than 400. A New York Times article was published several days later with the headline, “In Virginia, Gun Control Heats Up the Governor’s Race,” and the candidate’s dueling responses captured the partisan divide on the issue. Northam argued, “We as a society need to stand up and say it is time to take action. It’s time to stop talking.” Gillespie, who touted his “A” rating from the NRA, said it was “too early to discuss policy responses to gun violence.” In November Northam defeated Gillespie, winning by the largest margin for a Democrat in more than 30 years. On taking office in January 2018 Gov. Northam introduced several gun safety measures, but they failed in the Republican-controlled General Assembly. Then, on May 31, the Virginia Beach mass shooting happened, in which twelve people were killed at the city’s municipal center by a heavily armed lone gunman.

Days after the shooting, the Northam Administration held a somber press conference at which the governor announced he would call for a special session of the General Assembly in July to take up gun safety measures. At the special session, however, the Republican majority adjourned the session after only 90 minutes without debating any bills. As voters contemplated the November 2019 midterm legislative elections, a Washington Post–George Mason University poll found gun safety to be their top issue, and the gun safety movement went into high gear. Democratic candidates embraced the issue. John Bell, running for a previously red Loudoun County Senate seat, aired a prime-time television ad that showed him striding across a school athletic field to pick up a bullet casing as he promised he was “not afraid of the NRA.” Dan Helmer, an army veteran, ran on the slogan, “You shouldn’t need the body armor I wore in Iraq and Afghanistan to go shopping. This country has a gun violence crisis. We need action now.” On November 12, 2019 Virginia Democrats won both the House of Delegates and the State Senate and Democrats took full control of state government for the first time since 1994.

GUN POLITICS ONLINE

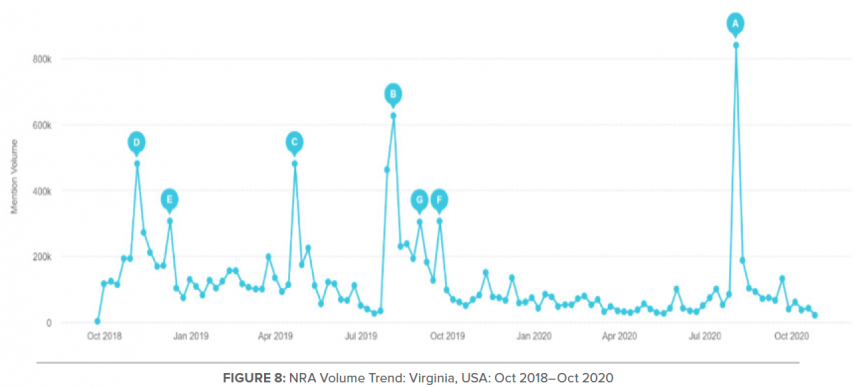

The declining influence of the NRA is visible in online discourse that reveals the growing prominence of pro-gun safety messaging and the heightened ability of pro-safety advocates to challenge well-established NRA talking points and dog whistles. Since October 2018, more than 10 million posts were generated making specific reference to “gun control,” “gun laws,” “gun safety,” and “gun politics” from roughly 2 million unique authors. In the same timeframe, Virginia, which emerged as a key battleground state in the transformation of the gun violence narrative, saw nearly 200,000 distinct social media messages referring to “gun control,” “gun safety,” and related terms, with roughly 32,000 unique users participating in this statewide discussion. In a reflection of the dominant role the NRA has played and continues to play in national discourse related to gun violence, specific reference to the “National Rifle Association” or “NRA” generated 12 million mentions, from roughly a million unique users. However, a closer look at this content reveals the changing dynamic of the organization’s online interactions, as the tone and focus on online discourse has shifted in the past few years and the NRA has found itself on the defensive.

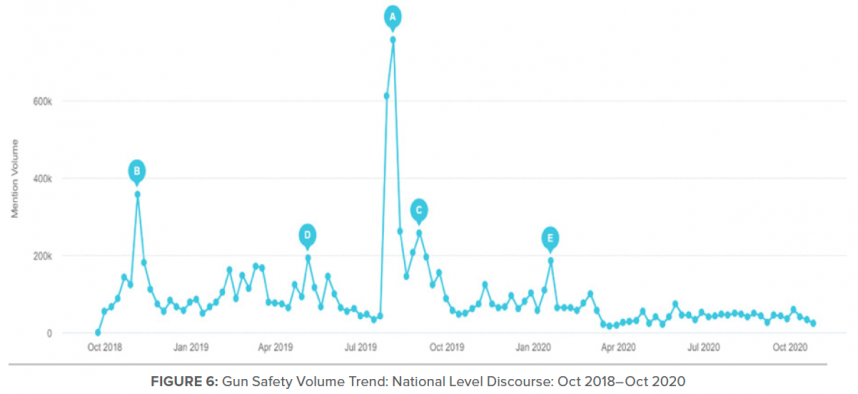

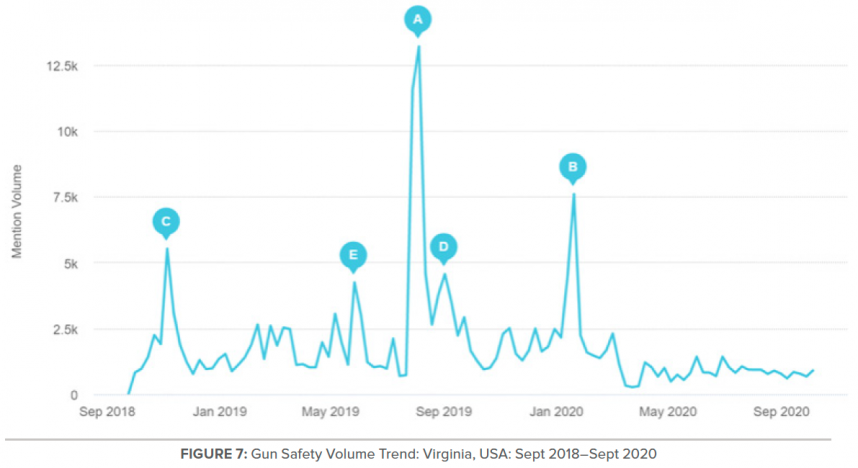

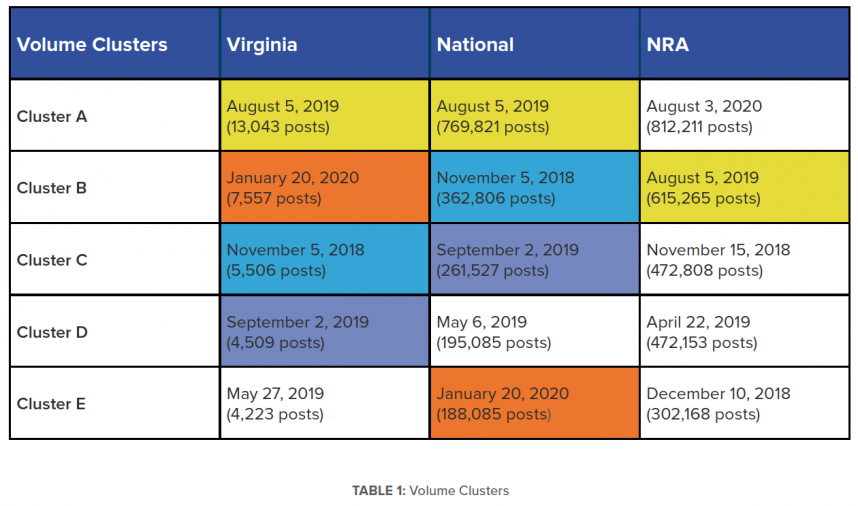

An exploration of volume trends, the number of unique posts generated over time, tells a complex story of how the gun control narrative has ebbed and flowed in recent years and the role of state-level advocacy in shaping the wider national discourse. Figure 6, 7, and 8 depict the various peaks and declines in online engagement. Letters A–F show the largest clusters of engagement when there was a significant increase in the number of unique social media posts generated about a given topic and a corresponding increase in the number of authors engaging in discussions about this topic.

In the past 2 years, there has been much overlap in the timeframes that have seen significant increases in engagement in Virginia and at the national-level discourse, with all but one increase in Virginia also seen at the national level. The majority of spikes were a direct result of widespread media coverage and public reactions following mass shootings events. As shown in Table 1, these pivotal dates include August 5, which saw two mass shootings in a 13-hour window in El Paso and Dayton, Ohio, and November 5, 2018, the day of the mid-term elections, in which candidates’ support or opposition to gun control legislation took center stage. A variety of announcements and events sparked the increased that peaked on September 2, 2019, including a mass shooting in the West Texas cities of Midland and Odessa on August [31], 2019 and Walmart’s announcement of its plans to reduce its gun and ammunition sales.

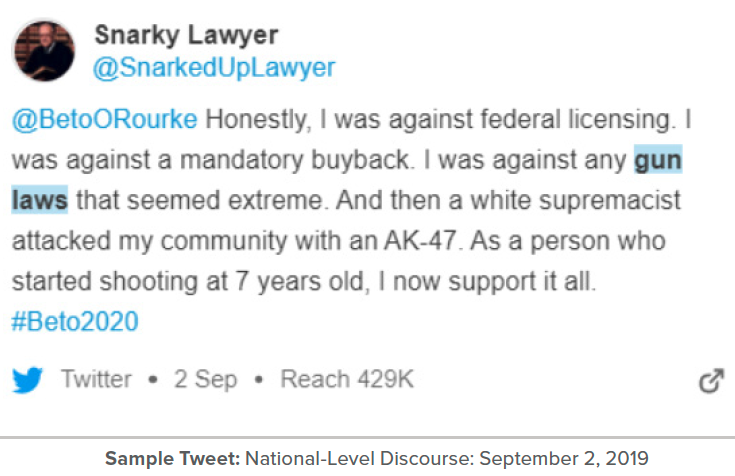

Within this timeframe, then Democratic presidential hopeful Beto O’Rourke featured heavily in online content for his outspoken condemnation of the NRA and staunch support for stricter gun laws. One of the most widely circulated tweets on September 2, 2020 came from self-proclaimed “Snarky Lawyer,” who explicitly called out the connection between guns and white supremacist violence and expressed support for Beto O’Rourke:

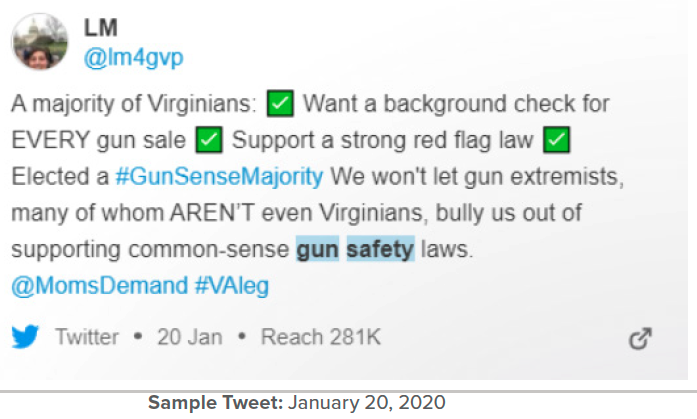

The volume clusters also indicate that Virginia took the lead in shaping national-level discourse on several occasions in the past few years. January 20, 2020 is the clearest example of the impact of Virginia and state-level advocacy on wider online discourse. The significant increase seen in cluster B is a direct result of the gathering in Richmond, Virginia of thousands of gun safety opponents (many of them armed), who came to protest Gov. Northam’s promise to pass a host of control measures. These events in Virginia were mirrored in national online discourse related to gun safety, as #GunSenseMajority, #VAleg, and @MomsDemand became trending topics. In the same 2-year period, volume trends related to the NRA remained largely distinct from national-level discourse related to gun control, gun safety, and related topics, reflecting the NRA’s strategy of deflecting or minimizing the issue of gun violence following mass shootings.

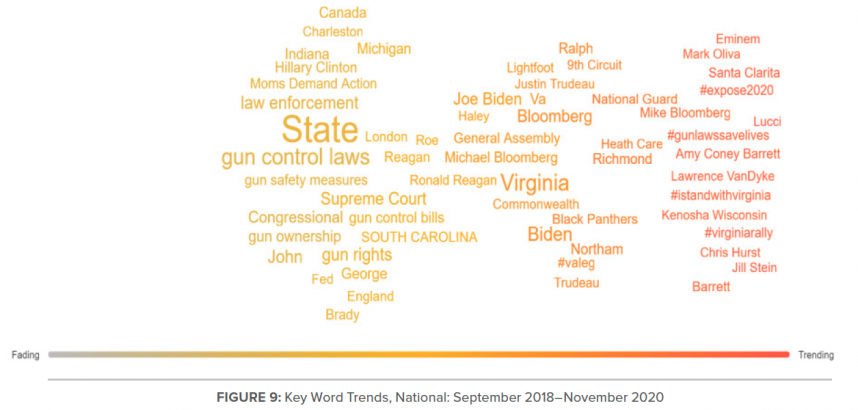

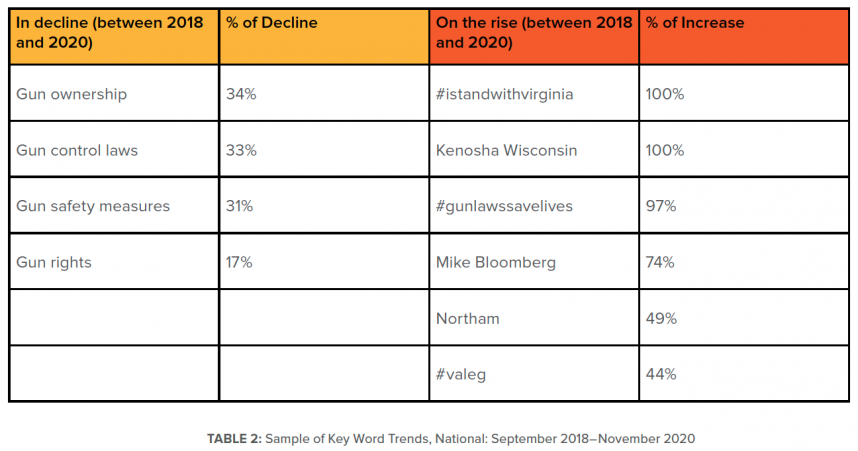

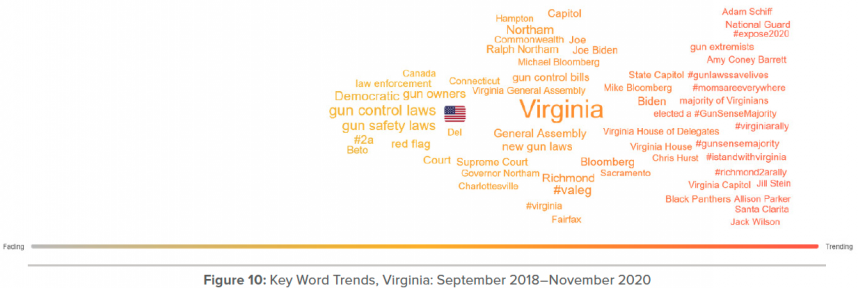

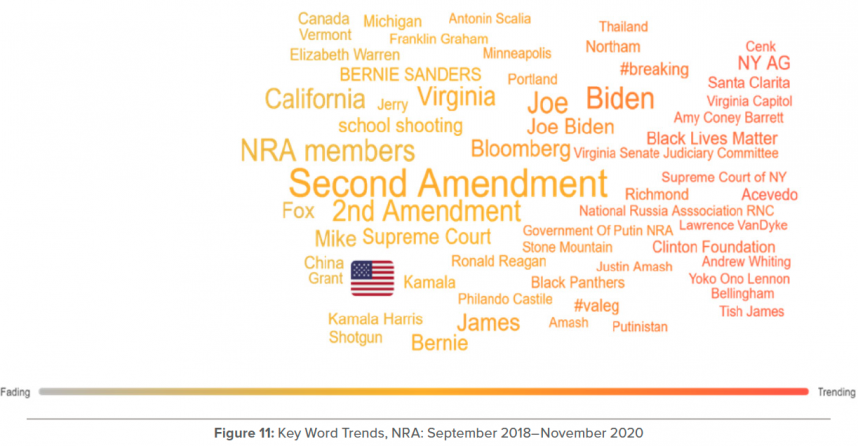

Alongside an examination of the volume of online content, the key phrases and terms that have tended to be included in posts reveal how language and terminology have shifted over time. Figures 9, 10, and 11 visualize the key phrases that have been used in association with gun safety between October 2018 and November 2020. The phrases on the right-hand side and shaded in darker orange have seen an increase in use, while the phrases on the left and shaded in lighter orange have seen a gradual decline.

At the national level, there has been a shift in the language used to discuss gun safety measures, with a 34 percent decline in use of “gun ownership” and a 33 percent decrease in use of “gun control laws” between 2018 and 2020. At the same time, references to “#istandwithvirginia” (and other phrases related to Virginia) and “Mike Bloomberg” have seen a dramatic increase. (During this time, Bloomberg also launched a bid for the Democratic presidential nomination, which could account for many of these references.) Kenosha, Wisconsin has also seen a 100 percent increase in mentions related to gun violence as a direct result of the killing of two protesters by 17-year-old Kyle Rittenhouse during a protest against police brutality.

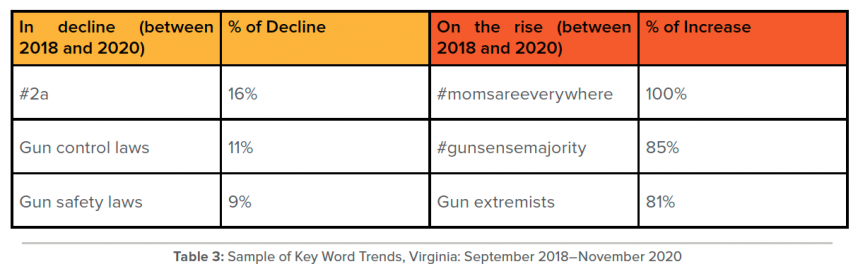

At the state level in Virginia, the gradual shift in language reflects the efforts and strategy of gun safety advocates, with #2a seeing a 16 percent decrease in the state, while “#momsareeverywhere,” “#gunsensemajority,” and “gun extremists” have seen significant increases over time.

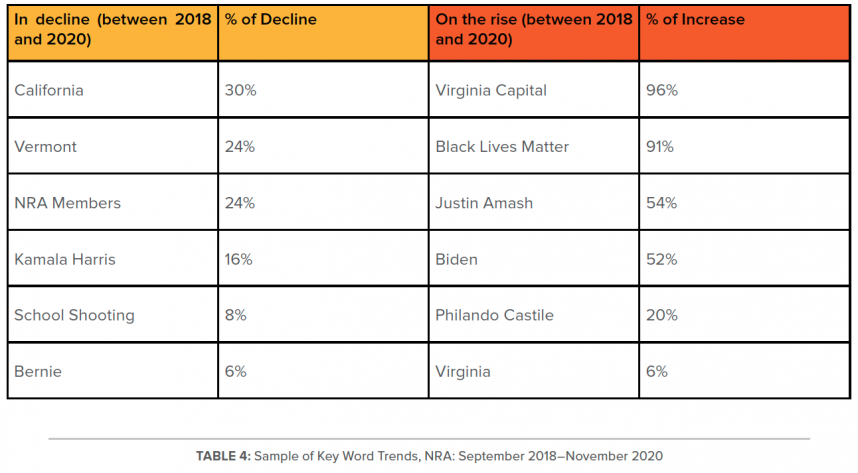

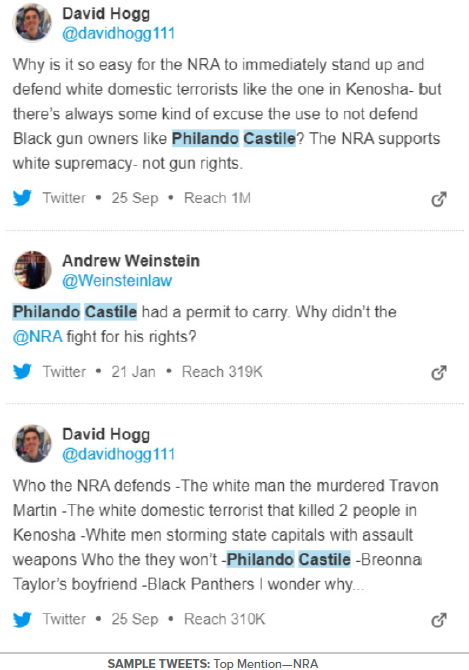

Finally, language trends related to the NRA reflect the shifting priorities and focus of the organization as mentions of “California” and “Vermont” have seen a significant decline, while a focus on “Virginia” saw a sharp increase. Key word trends also reveal the declining engagement of NRA members and the growing ability of NRA opponents to set the organization’s messaging agenda. As seen in Table 4, reference to “NRA Members” declined by 24 percent between 2018 and 2020, while references to “Black Lives Matter and “Philando Castile” saw a significant increase as a result of anti-NRA voices online.

The sample of tweets below showing the relationship between mentions of “Philando Castile” and the “NRA” are just a few examples of how gun safety advocates have explicitly called out the NRA as a racist and white supremacist organization in recent years.

CONCLUSION

On December 10, 2020 Everytown for Gun Safety released its “roadmap” for how the new Biden Administration can “tackle gun safety through executive action in the first hundred days and beyond.” The roadmap lists four actions that are prioritized by the gun safety movement.31 At the same time, the organization released the findings of a new poll demonstrating that a large majority of voters support the movement’s goals. According to the survey of more than 15,000 voters, an unusually large sample, 70 percent, agree that gun violence “is an urgent issue that the federal government needs to address quickly next year, alongside the economy & COVID-19” and 68 percent agree that “our nation’s gun laws should be stronger than they are now.”[32]

As the country enters a new era of gun politics with a new administration that supports stricter gun laws, the new narrative will be put to the test. Gun safety proposals that have been languishing in Congress will advance and generate intense debate. If the past is any guide, we know that the gun lobby and its supporters will mount strong opposition to any tightening of the rules. But today a new three-point narrative is taking hold:

- The NRA is no longer the most powerful lobby.

- The voters want action.

- Voting for “gun sense” laws is a win-win—lives will be saved and backers will win elections.

Will this shift embolden a majority of members of Congress to vote for new federal gun safety regulations?

1 Gun sales hit a record high during the pandemic and Black Lives Matter protests. Three million more guns than usual had been sold as of July 2020, and first-time buyers were driving the increase. https://www.npr.org/2020/07/16/891608244/protests-and-pandemic-spark-record-gun-sales

2 According to the Gallup Poll, 57 percent of Americans favored stricter gun laws in 2020. Note that this figure tends to rise and fall with news of mass shootings. For example, in 2018, the year that saw the killing of seventeen students and faculty members at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, FL and the public outcry that followed, 67 percent favored stricter gun laws. https://news.gallup.com/poll/1645/guns.aspx

3 Adam Winkler, Gun Fight, p. 253.

4 Adam Winkler, Gun Fight, p. 254.

5 The Brady Bill, named for James Brady and spearheaded by his wife, Sarah, mandated a 5-day waiting period for handgun purchases so that law enforcement could undertake a background check.

6 Alec MacGillis, “This is How the NRA Ends,” The New Republic, May 28, 2013.

7 https://www.opensecrets.org/orgs/totals?id=d000000082

8 United States v. Emerson, 270 F.3d 203, cert. denied, 536 U.S. 907, is a decision by the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit holding that the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution guarantees individuals the right to bear arms.6 Alec MacGillis, “This is How the NRA Ends,” The New Republic, May 28, 2013.

9 Based in Arlington, VA, the Institute for Justice describes itself as a “libertarian public interest law firm…that litigates to promote property rights, economic liberty, free speech, and school choice.”

10 Initially, the NRA did not support this litigation. At the time, it was not clear that a majority of Justices would endorse the individual right interpretation of the Second Amendment and the organization was afraid that a ruling would be unfavorable. The organization eventually came to support the effort and filed a friend-of-the-court brief.

11 The other mass shootings in 2007 were Trolley Square Mall, Salt Lake City, five dead; post-homecoming party at an apartment, Crandon, WI, six dead; Westroads Mall, Omaha, eight dead.

12 The change was driven by a thirteen-point increase in the percentage of white men who prioritized the right to own guns over gun control, from 51 percent in 2008 to 64 percent in 2009.

13 In 2011, the Violence Policy Center calculated that the NRA had received between $14.7 million and $38.9 million from gun industry “corporate partners.” Blood Money: How the Gun Industry Bankrolls the NRA, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T4pI_9R2Dmg.

14 Chris Murphy, The Violence Inside Us: A Brief History of an Ongoing American Tragedy, p. 161.

15 Shannon Watts admits that she didn’t realize that in 2000 there had been a Million Mom March on the National Mall calling for gun reform after the Columbine shooting. That march had been organized by a group of volunteers to fall on Mother’s Day, and it attracted some three-quarters of a million people with satellite events happening in more than 70 cities around the country. Million Mom March chapters formed and soon merged with one of the country’s oldest gun violence prevention organizations, the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence. But the energy generated by the march dissipated in the face of such an inhospitable political environment (Waldman, p. 151).

16 Formerly known as Handgun Control, Inc. and founded in 1980.

17 Founded in 1974.

18 Founded by Mayor Michael Bloomberg of New York City and Mayor Thomas Menino of Boston in 2006.

19 Shannon Watts, Fight Like a Mother: How a Grassroots Movement Took on the Gun Lobby and Why Women Will Change the World, p. 29.

20 Open carry refers to the practice of “openly carrying a firearm in public,” as distinguished from concealed carry, where firearms cannot be seen by the casual observer. Thirty-one states allow open carrying of a handgun without a license or permit; fifteen states allow it with some form of license or permit.

21 Shannon Watts, Fight Like a Mother: How a Grassroots Movement Took on the Gun Lobby and Why Women Will Change the World, p. 107

22 Alec MacGillis, “This is How the NRA Ends,” The New Republic, May 28, 2013.

23 Minnesota, Indiana, Louisiana, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont, Wisconsin, and Washington.

24 Melissa Chan, “‘They Are Lifting Us Up.’ How Parkland Students Are Using Their Moment to Help Minority Anti-Violence Groups,” Time, March 24, 2018.

25 The Giffords PAC spent close to $5 million backing gun sense candidates, and Everytown spent more than $30 million.

26 Two additional gun-control bills were signed that year after Northam proposed amendments to them. One of those bills requires evidence that anyone subject to a protective order has surrendered their firearms within 24 hours and was amended so that those who fail to comply would be found in contempt of court. The other bill allows for municipal regulations of firearms in public buildings, parks, and recreation centers and during public events.

27 The Virginia Center for Public Safety is a small nonprofit founded in 1992 dedicated to reducing gun violence in the state.

29 Rachel Weiner, “Gov. McAuliffe’s gun control efforts for Virginia die in Senate Committee,” Washington Post, January 26, 2015.

30 Reid J. Epstein, “Bloomberg’s gun control group calls for a raft of executive actions from Biden,” The New York Times, December 10, 2020.

31 1. Keep guns out of the hands of people who shouldn’t have them by strengthening the background check system. 2. Prioritize solutions to the city gun violence devastating communities every day. 3. Heal a traumatized country by making schools safe, confronting armed hate and extremism, preventing suicide, and centering and supporting survivors of fun violence. 4. Launch a major firearm data project and protect the public with modern gun technology.

32 https://everytown.org/documents/2020/12/everytown-mc-analysis.pdf/