What are Community Values and why are we promoting them now?

Community Values are long held American values. Community Values say that we share responsibility for each other, that our fates are linked. Whether described as interconnection, mutual responsibility, or loving your neighbor as you love yourself, Community Values are moral beliefs, a practical reality, and an important strategy.

For the past 30 years, the theme of individualism has dominated our national dialogue and common culture. Instead of favoring policy that works for everyone, this approach tells people to go it alone. We see the results in our fragmented healthcare system, the divisive debate on welfare reform, and in recent, though unsuccessful, attempts to overhaul social security.

Americans are becoming tired of this individualistic approach to policy, and to life in general. The country is ready for a new inclusive vision and a new generation of positive solutions. It’s time to reclaim values in the political conversation. It’s time to turn Americans’ attention to our long history of working collectively, standing up for each other, and upholding the common good.

The Community Values Toolkit

Included here are ideas, advice, and resources for moving toward this new political conversation, beginning with the 2008 presidential election.

- Community Values Phrase Basket

- General Talking Points

- Building a Message

- Examples of Language and Usage

- Sample Media Pieces

Community Values Phrase Basket

We’re All in it Together – So Let’s Say the Same Things!

Below we’ve provided the drumbeat terms that we plan to track and measure the use of, to see how Community Values language is faring in the political debate. We’ve also included some terms to use to define the opposition.

It may feel awkward at first to weave the terms into your communications. But if you think about how others have used familiar terms such as “family values” or “tax relief,” you may start to get the idea of what it looks like when a term infiltrates the popular vocabulary.

Phrase Basket

Community Values Phrases: The Opposition:

Drumbeat Phrases:

- Community Values ideology) “You’re on your own” (mentality, approach,

- Policies of Connection “Go it alone” (mentality, approach, ideology)

Policies of Isolation

Also suggested depending on audience:

- (We’re all) In it together Community neglect

- Stronger together Everyone for themselves

- The Common Good Pull yourself up by your bootstraps

- Sharing the ladder of opportunity Pulling up the ladder behind you

- On the same team Standing alone

- Looking our for each other Leaving people behind

- Standing together

- Shared or Linked Fate

General Talking Points

- This is really about Community Values. Are we going to acknowledge that we’re all in this together, and that we need to look out for each other? Or are we going to tell everyone to go it alone?

- What’s missing here are Community Values. Telling people that [issue] is their individual problem is not only unworkable, it’s contrary to our nation’s long-held belief that we’re stronger together, that we look out for each other and work for the common good.

- What we need are more policies of connection that recognize our reliance on each other, and how much more we thrive when we stand together. Simply telling people that they’re on their own is not an American option.

- Look, we’re all on the same team here. This country thrives when we draw on our Community Values to solve our problems. There are those who say that we each need to figure it out on our own, but that go it alone mentality is obviously unworkable and not an option in today’s interconnected world.

- I’m tired of the myth that we should all just pull ourselves up by our bootstraps, buck up, and get on with it. When it comes to health care, to our public school system, to the future of social security, I don’t want politics of isolation to drive public policy. We’re in this together, and we’ll rise together.

- We all know instinctively that we’re stronger together. And history shows that when we work together to solve our problems, placing the common good as a top priority, we all move forward. When we leave people behind, we all suffer. I’m for a country that embraces those kind of Community Values again, let’s leave the “go it alone” mentality behind.

- We have to recognize that we live in an interconnected world. Our actions have consequences beyond ourselves. Our fates are linked. Insisting on an old-fashioned go it alone mentality is not only unworkable, it’s just wrong.

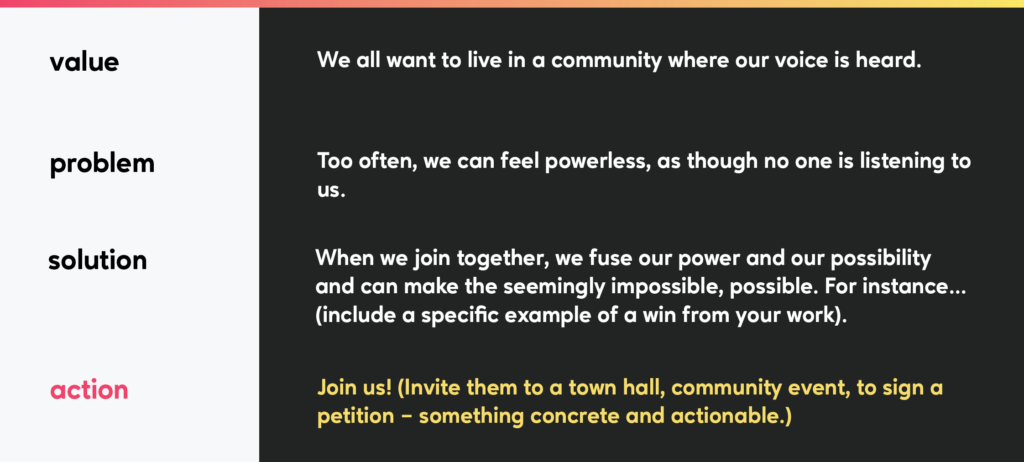

Building a Message

Where possible, our messages should: emphasize the values at risk; state the problem; explain the solution; and call for action.

o Why should your audience care?

o Documentation when possible

o Avoid issue fatigue – offer a positive solution

o What can your audience concretely do? The more specific, the better.

Example:

- Our shared Community Values mean that we come together to solve our problems. We look our for each other and understand that leaving anyone behind is not an option.

- But we’re falling short of that ideal—millions of Americans can’t live on the wages they are paid for full-time work. By refusing to address this situation in a meaningful and realistic way, we’re failing these workers and members of our community.

- We need to ensure that anyone who is working full time can support their family.

- Tell your Member of Congress to support a real and living wage. It’s about workers, families and supporting Community Values.

Messaging Questions

Some useful questions to consider when building a message include:

- Who are the heroes and villains of this story? We need to think through various roles played by the characters in our stories. For instance, a common conservative frame is that of tax relief. If people need “relief” from something, it is an affliction. If taxes are an affliction, they are never good and those who relieve us of them are heroes. Those who propose more affliction are villains. Using this term, then, is not helpful to anyone promoting increased government support for programs.

- Who does the narrative suggest is responsible for solutions? The conservative theme of individualism suggests that as individuals, we should solve the bulk of our problems ourselves. Instead of an inclusive health care system, for instance, we should have individual health savings accounts. Focusing on individual success stories can have the same effect. The story of an immigrant coming to this country, starting a business and becoming a model citizen can be helpful in many ways, but it doesn’t underscore the need for community or societal level programs to help newcomers. The solution is portrayed at an individual rather than a systemic level.

- What are the long term implications of this narrative? Does it point toward the solutions we want? Sometimes, in hopes of providing a dramatic, media friendly story advocates use examples that can lead audiences in unhelpful directions. For example, in appealing for money for a specific child abuse prevention program, advocates might use dramatic statistics of children injured or killed each year by abuse and neglect. These statistics will get media coverage and draw attention to the problem of child abuse. However, they are unlikely to lead audiences to the solution that prevention advocates desire. If the long term goal is to increase funding for prevention programs that support parents, advocates have instead made their audience less sympathetic to parents, and more supportive of punitive measures that do not include prevention.

- Does the story inadvertently invoke unhelpful cultural narratives? For instance, in talking about health care, we sometimes use a consumer frame. But this competitive frame is actually unhelpful if the solution we want to promote is universal care. Consumerism implies that we are economic players competing for limited resources. Instead, we want to promote the idea that the system is stronger when we’re all in it.

- Does the story use our opponents’ narrative? Consider the recent debate about proposed immigration reform. Many advocates engaged in conversations about whether reform would or would not grant “amnesty” to undocumented immigrants. But by focusing on the word “amnesty,” advocates strengthened the “law breaker” narrative. In this story, “illegal” immigrants and those who fail to punish them are the villains. However well intentioned, arguments that immigration reform is “not amnesty” reinforce opponents’ arguments. We should be careful to avoid using such stories, particularly when we talk to persuadable audiences might support our positions if we framed them differently.

Community Values Caveats

Additional considerations when building a community values message.

Attacking personal responsibility

It’s important to note that promoting Community Values should not appear to abandon all forms of individualism. Americans believe strongly in the value of individualism and “personal responsibility.” And that belief cuts across ideological lines.

People want individuals to take responsibility and also to control their own destiny. These worries can prevent them from fully embracing Community Values if they view such values as letting people off the hook, providing handouts, or removing individual choices and empowerment. Bringing the idea of opportunity into the conversation can help us to point out that systemic barriers to opportunity prevent many individuals from moving forward.

Talking about interconnections that harm, rather than help, us.

In stressing community values, we want to emphasize the ties that bind us as neighbors, workers, Americans and humans. Our fates are connected, so it’s in all of our best interests to move forward together. However, we should not imply that we only need to care about other people’s circumstances if it’s in our best interest.

For instance, advocates might make the case that we should cover all immigrants in new health care reform plans because if we don’t, we are at risk of becoming infected with any diseases they carry. While invoking a linked theme, this narrative isn’t helpful in the long-run as it implies 1) that immigrants are a danger to us and 2) that if their health does not affect us, we don’t need to worry about including them.

Instead, we should emphasize that recognizing our connections is important not only to protect our own interests, but also to understand how we’re part of something bigger.

Invoking the charity frame when promoting the common good.

The term common is useful because gives a name to the entity we hope to benefit. It names exactly what we want to win: an outcome that is good for the community. However, this term can also lead people to think of charity first. This idea says that we help others – often termed the “less fortunate” – through “handouts.” There are certainly heroes to this story, but if we’re not careful, those benefiting from charity can be painted as the villains. In addition, this is a judgmental frame that does not empower groups that have typically faced the biggest barriers to opportunity. In invoking the common good, then, it’s important to point out the solutions we seek: shared power and responsibility, not a one-way, “privileged to unprivileged” exchange.

Using exclusive or nostalgic versions of community

Sometimes we lean toward limited or nostalgic Norman Rockwell illustrations of community that call up ideas of “the old days”, the Eisenhower years, childhood neighborhoods, or our own, limited surroundings. This is problematic for several reasons.

Neighborhoods, for one, are rarely inclusive, so that metaphor alone can be troubling. We need Community Values to mean benefit for everyone, not communities pitted against each other only looking out for their “own.”

Similarly, “the old days” didn’t hold a lot of promise for many groups. People do like the idea of old-fashioned small towns where everyone knows each others’ names, families are intact, and white picket fences prevail. But the old days in the form of 1950’s America was also home to racism, segregation, limited opportunity for women, and hostile to gays and lesbians.

Community Values should mean drawing on our shared history of collectively solving our problems. We can do this by using examples of how we’ve solved problems collectively, such as the New Deal or Civil Rights. This is an instance where patriotism can aid our cause by igniting people’s pride in our ability to work together.

- History shows we move forward when we invest in an effective partnership between government and our people. Think of child immunization programs that have wiped out devastating diseases in our country. Think of our Social Security system that has enabled millions of seniors to stay out of poverty. Medicare has kept them safer and healthier without regard to their wealth, race, or region of the country. Think, even, of the interstate highway system, which connected us as a single prosperous nation. To address our health care crisis effectively, we need to invest in those kinds of policies of connection.

Applying Community Values to Health Care

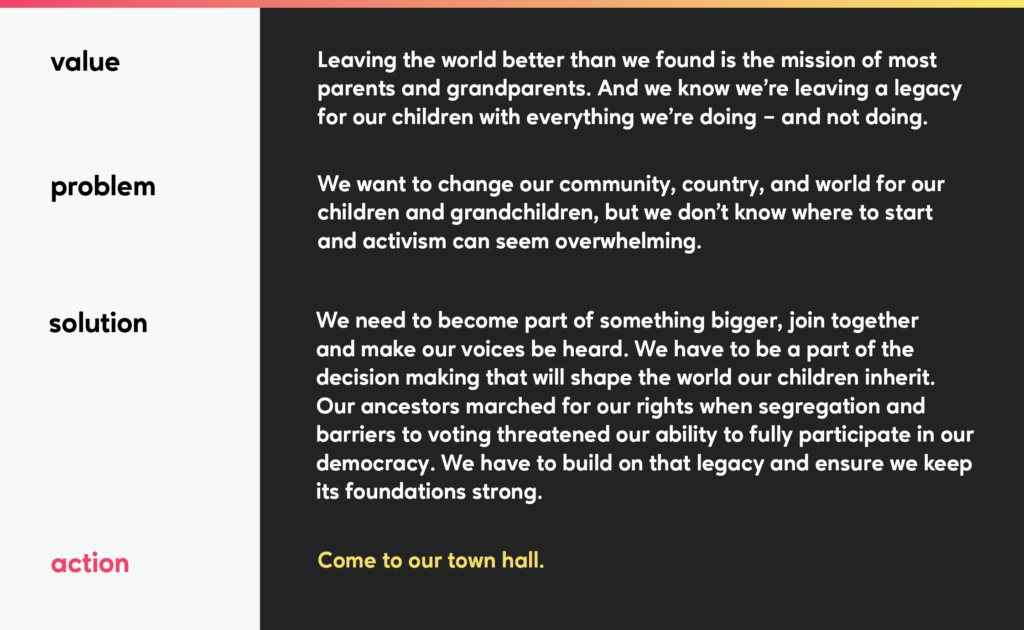

Using the Value, Problem, Solution, Action Model

Value: When it comes to health care, we’re all in it together. We’re a stronger nation when everyone has the health care they need.

Problem: So when 47 million Americans lack health insurance, our whole nation’s health and prosperity are at risk.

Solution: We need policies of connection in our health care system that guarantee access to affordable health care for everyone in our country.

Action: Ask the presidential candidates if they’ll embrace Community Values and guarantee health care for every single member of our nation.

Messaging Examples

- Embracing Community Values means creating a health care system that works for everyone. Anything less leaves people behind to suffer poor health, bankruptcy, and even early death. We thrive when everyone moves forward, so making sure health care is available for everyone is critical to our nation’s success.

- Health care reform should create a system that works for everyone. That means health care has to be universal, free of racial and ethnic bias, comprehensive, and designed to meet community needs. If one element is missing, the system isn’t complete. For example, we might expand insurance to everyone in a state, but that doesn’t mean everyone is getting the same quality of care. We need policies of connection here, that look at and address all the pieces of our health care system equally. In taking a true Community Values approach to health care, we can’t overlook quality, access or other important issues when we think about coverage.

- When it comes to health care, it doesn’t make sense to force people to “go it alone.” We need to promote a Community Values approach. When we spread resources fairly, everyone gets the care they need before problems become costly and more difficult to treat. All social insurance rests on this idea of pooling resources and sharing risk as broadly as possible, recognizing that we’re all in it together. This is particularly important in health care.

- Our history shows that we’re stronger when we tackle tough issues together. When we have worked together for clean and healthy drinking water, to provide child immunizations, or to reduce smoking, we’ve all benefited. We’re currently looking for ways to address childhood obesity together. We know that this Community Values approach will work better than telling families to figure it out on their own.

Applying Community Values to Immigration

Using the Value, Problem, Solution, Action Model

Value: Immigrants are part of the fabric of our society—they are our neighbors, our coworkers, our friends.

Problem: Reactionary policies that force them into the shadows haven’t worked, and are not consistent with our values. Those policies hurt us all by encouraging exploitation by unscrupulous employers and landlords.

Solution: We support policies that help immigrants contribute and participate fully in our society.

Action: Ask your candidates what they would do to ensure that immigrants are treated fairly and given a voice in this country.

Messaging Examples

- For America to be a land of opportunity for everyone who lives here, our policies must recognize that we’re all in it together, with common human rights and responsibilities. If one group can be exploited, underpaid and prevented from becoming part of our society, none of us will enjoy the opportunity and rights that America stands for.

- Reactionary, anti-immigrant policies have repeatedly failed to fix the problem. They’re not workable and they’re not fair to citizens or to immigrants. They hurt all of us and make a bad system worse. We’re all in this together, and such policies of exclusion violate the core sense of community that has always driven the policies that have moved this country forward.

- Our immigration system should reflect that immigrants have always been part of this nation. But immigration isn’t just a domestic issue; it’s an international reality. We need comprehensive immigration reform that works for the good of all and reflects the interdependence of nations, communities, and workers.

- As long as our federal immigration system is broken, it’s up to local communities to decide how to work with immigrants. Would you rather live in a place that understands the meaning of Community Values, of working together with immigrants to find solutions? Or a place that moves toward punitive, exclusionary measures? In this country, we value people, and we value treating them the right way. Cooperation and common sense solutions for the common good are the way to go.

Applying Community Values to Workers’ Issues

Using the Value, Problem, Solution, Action Model

Value: America is supposed to be the land of opportunity, where we rise together and leave no one behind.

Problem: But too many families are living on the edge of this dream, shut out by unfair labor practices and wages that don’t even put them at the poverty level.

Solution: Our policies must recognize that we’re all in it together, with common human rights and responsibilities. If one group can be exploited, underpaid and prevented from becoming part of our society, none of us will enjoy the opportunity and rights that America stands for.

Action: Ask your candidates what they would do to ensure that all workers are treated fairly and given a voice in this country.

Messaging Examples

- Embracing Community Values means that we share a basic concern about one another, and accept that the well being of each one of us, and each of our families ultimately depends on the well being of all of us. As a wealthy nation, we have a shared responsibility to use our collective wealth to establish and support programs that help people rise out of poverty.

- The fates of all workers are connected. When some employers pay workers below the minimum wage or don’t pay them for working overtime, these practices quickly spread and other employers try to profit by following these bad examples. This type of race to the bottom ultimately leaves workers competing with each other over lower wages and fewer benefits. Instead of emphasizing cost-savings and competition, we need to encourage ethical and compassionate business practices that are accountable to the community, and cooperation among workers.

- We, as a community, must demand that all workers are fairly paid for the hard work they do. This doesn’t just make sense from the perspective of workers, but it’s good for society as a whole. Providing workers with a living wage makes it possible for them to better care for their families, save for the future, contribute to the community and build a stronger America.

- A business is just another part of our community. But all too often, most of the people in the community have little or no voice or power in the business decisions that affect the community. We need business interests to recognize that they are part of us and have a responsibility to respect the needs of the community. That means paying workers a fair wage, being good stewards of the environment that we all share, and giving back to the community.

Sample Letter to the Editor

Letters to the editor are a quick and effective way to weigh in on issues that the media frequently cover. Often, more people read the letters page than the pages where the original article appeared or the opinion page. Letters need to be short – about 150 words – so it’s best to focus on one point. In the examples below, the letters focus on weaving Community Values into a call for federal immigration reform.

Letters do not need to be negative. Responding to an article that positively portrayed an issue you care about can set a tone friendlier to Community Values than the confrontational tone central to letters of disagreement.

To the Editor:

Thank you for your informative portrait of one town’s experience with immigration. This piece shows that we have a long way to go. But it also illustrates the community values that will ultimately help us address this issue.

Iowa needs and values immigrants, their work, and their contributions to the community. Yet the state’s ability to welcome its newest residents continues to be strangled by the federal governments’ inability to pass reasonable legislation. Instead of giving into the politics of division and isolation favored by anti-immigration forces, these Iowans have chosen to think about immigration in a community-spirited, humane and practical manner. The federal government should take note.

To the Editor:

Your recent article about immigration was a real eye opener. In the divisive rhetoric we hear in the immigration debates, I feel that this human story of community values is so often lost. Absent in this story were the one dimensional stereotypes of oppressive law enforcement or problematic immigrants. Instead, we saw a community-minded portrait of people working together to make the best of a system over which they have no control.

I believe we need more realistic reflections about what immigration really means to communities. Immigrants are already clearly a part of the community, why can’t the federal government not clear the way for positive integration, so that everyone can move forward?

Sample Press Release

Press releases are more than an opportunity to publicize an event or report. They are also messaging vehicles. While the main text of the release should be primarily informative – who, what, when, where, and why – you have a lot of room in the quotes you provide for elevating Community Values.

Heartland Presidential Forum Challenges Candidates:

How can we embrace community values?

News Release

DES MOINES – Ten presidential candidates will gather at Hy Vee Hall on Saturday, December 1 to answer Iowans’ questions about community issues ranging from health care and education to social justice and factory farming. Organizers, who expect an audience of over 5,000, say the theme of the debate, “Community Values,” is meant to focus candidates’ attention on the idea that the common good is too often overlooked in favor of individual interests.

“These core issues are important to Iowans,” said XXXX. “And it’s important that we focus on solving the challenges they present through the lens of community and the common good. When we think of how we’re stronger together, how we solve our problems more effectively when we’re all involved in the process, we all come out ahead.”

[Event details]

“Community values are such an obvious fit for Iowans,” said XXXX. “We look out for each other here, and we resist the politics of isolation that tell us that we have to solve societal problems on our own. Whether it’s health care or the environment, we’re going to do this together, with a positive role for government, and leave no one behind.”

[Continued details]

“We became involved in this event because of its focus on community,” said XXXX. “There’s a lot of lip service to valuing community, but we wanted to force candidates to explain what that really means to each of them on a policy level. We need more policies of connection that recognize how we’re all in this together, and draw on our collective strength. So we’re actively rejecting the “go it alone” approach to policy.”