The term “racial profile” first entered the American lexicon in January 1998 when an AP story titled “Veteran Cop Goes on Trial; Race an Issue in Traffic Stop” was published in several regional newspapers. The article described the trial of Aaron Campbell, a Black man who happened to be a police officer, who was pulled over by sheriff’s deputies in Orange County, Florida and then pepper sprayed, wrestled to the ground, and arrested when he objected to the stop:

Campbell is scheduled to go on trial today on charges of felony assault and resisting arrest with violence. His lawyer said the stop was illegal, and the only thing Campbell was guilty of was DWB, driving while black, and fitting a profile that Orange County deputies use to identify motorists to be stopped and searched for contraband…. The Orange County sheriff’s office says stops aren’t based on a racial profile. (AP, January 12, 1998)

“Racial profiling” was mentioned in a smattering of newspaper articles over the course of 1998, but by 1999 it had vaulted to the top of the nation’s public policy agenda. It was the subject not only of thousands of articles, editorials, and television and radio broadcasts, but also of Congressional and state legislative hearings and proposals. In 2000, both presidential candidates, Al Gore and George W. Bush, deplored it during their campaigns, and both vowed to issue executive orders banning it if elected. By 2001, more than a dozen state legislatures had passed new laws requiring their law enforcement agencies to collect race and ethnicity data for all traffic stops. By the end of 1999, a majority of Americans, both Black and white, believed that racial profiling was both widespread and unfair.[1]

This case study describes the narrative shift that occurred in just 3 years, between 1999 and 2001, and how advocates made it happen. It also describes the gradual weakening of resolve to end racial profiling in the aftermath of 9/11 and the reemergence of the anti-racial profiling narrative in the years since the murder of Trayvon Martin in 2012 and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement.

METHODOLOGY

INTERVIEWEES:

- John Crew, Founding Director of the ACLU’s Campaign Against Racial Profiling

- Ira Glasser, former Executive Director of the ACLU

- David A. Harris, author of Profiles in Injustice

- Wade Henderson, former President and CEO of The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights

- Laura W. Murphy, former Director of the ACLU Washington Legislative Office

- Reggie Shuford, Executive Director of the ACLU of Pennsylvania and former lead racial profiling litigator for the ACLU

OTHER SOURCES CONSULTED:

- Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. The New Press, 2010.

- Frank R. Baumgartner, Derek A Epp, and Kelsey Shoub, Suspect Citizens: What 20 Million Traffic Stops Tell Us About Policing and Race. Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- David Cole, No Equal Justice: Race and Class in the American Criminal Justice System. The New Press, 1999.

- David A. Harris, Profiles in Injustice. The New Press, 2002.

- Khalil Gibran Muhammad, The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America. First Harvard University Press, 2019.

- Craig Reinarman and Harry G. Levine (Eds.), Crack In America: Demon Drugs and Social Justice. University of California Press, 1997.

MEDIA AND SOCAL MEDIA RESEARCH

To identify media trends, we developed a series of search terms and used the LexisNexis database, which provides access to more than 40,000 sources, including up-to-date and archived news. For social media trends we utilized the social listening tool Brandwatch, a leading social media analytics software that aggregates publicly available social media data.

BACKGROUND

The dangers of “driving while Black” were well known to Black people long before the late-1990s, as Ric Burns’s recent film of the same name documents so effectively. Efforts to control African Americans’ mobility date back to the arrival of the first enslaved Africans in the New World in 1619. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1783 authorized local governments to seize and return escapees to their owners and empowered any white person to question any Black person they saw. But the “war on drugs,” declared by President Reagan in 1982, introduced a new tool to impede the free movement of motorists of color. In 1986, in the midst of the crack cocaine “epidemic,” which was depicted as a Black, inner-city problem, the Drug Enforcement Agency launched “Operation Pipeline.” This drug interdiction program ultimately trained 27,000 law enforcement officers in 48 states to use pretext stops (e.g., going slightly over the speed limit or failing to signal) in order to search for drugs. The training encouraged the police to use a race-based “drug courier profile” to pull over motorists; consequently, civil rights organizations saw an uptick of complaints of unfair treatment on the nation’s highways. By the early-1990s, the uptick had become a flood. Disturbing stories like the following examples began to appear in the media, often in the context of civil rights lawsuits brought by racial profiling victims:

An elderly African-American couple sued the Maryland State Police yesterday, alleging that a search of their vehicle and possessions along Interstate 95 by troopers was an unlawful act of racial discrimination and false imprisonment. The suit, stemming from a July 12, 1994, traffic stop in Cecil County, was filed in Baltimore County Circuit Court by the American Civil Liberties Union on behalf of Charles Carter, 66, and Etta Carter, 65. The Carters of Mount Airy, Pa., allege that they were traveling home on their 40th anniversary after visiting a daughter in Florida when they were stopped and detained for several hours while police “methodically examined the contents of virtually every item” in their rented minivan, scattering items on the roadside.

Officials in Eagle County, Colorado paid $800,000 in damages in 1995 to Black and Latino motorists stopped on Interstate 70 solely because they fit a drug courier profile. The payment settled a class-action lawsuit filed by the ACLU on behalf of 402 people stopped between August 1988 and August 1990 on I-70 between Eagle and Glenwood Springs, none of whom were ticketed or arrested for drugs.

In California, San Diego Chargers football player Shawn Lee was pulled over, and he and his girlfriend were handcuffed and detained by police for half an hour on the side of Interstate 15. The officer said that Lee was stopped because he was driving a vehicle that fit the description of one stolen earlier that evening. However, Lee was driving a Jeep Cherokee, a sport utility vehicle, and the reportedly stolen vehicle was a Honda sedan.

In addition to compelling stories of innocent Black people being stopped, searched, and humiliated on interstate highways, the lawsuits led to the collection of hard data to prove the plaintiffs’ contention that racial profiling was real. Dr. John Lamberth, a Temple University Professor of Psychology with expertise in statistics, was retained by plaintiffs to carry out a series of studies. He designed a research methodology to determine first, the rate at which Black people were being stopped, ticketed, and/or arrested on a section of a given highway, and second, the percentage of Black people among drivers on that same stretch of road. He also measured the population of violators of traffic laws, broken down by race to see whether disproportionate stops of drivers of color were due to their driving behavior, rather than racial profiling. These studies were carried out in New Jersey, Maryland, Illinois, and Ohio, and they all came to the same conclusion: state troopers were singling out motorists of color for discriminatory treatment. In Maryland, although only 17 percent of the drivers on the relevant roadway were Black, well over 70 percent of those stopped and searched were Black. In New Jersey, the race of the driver was the only factor that predicted which cars police stopped. Professor David A. Harris, who has written widely on the subject, observed:

These findings and those in other studies—performed in different places, at different times, with different data, and involving different police departments—all point in the same direction: The disproportionate use of traffic stops against minorities is not just a bunch of stories, or a chain of anecdotes strung together into the latest social trend. On the contrary, it is a real, measurable phenomenon.[2]

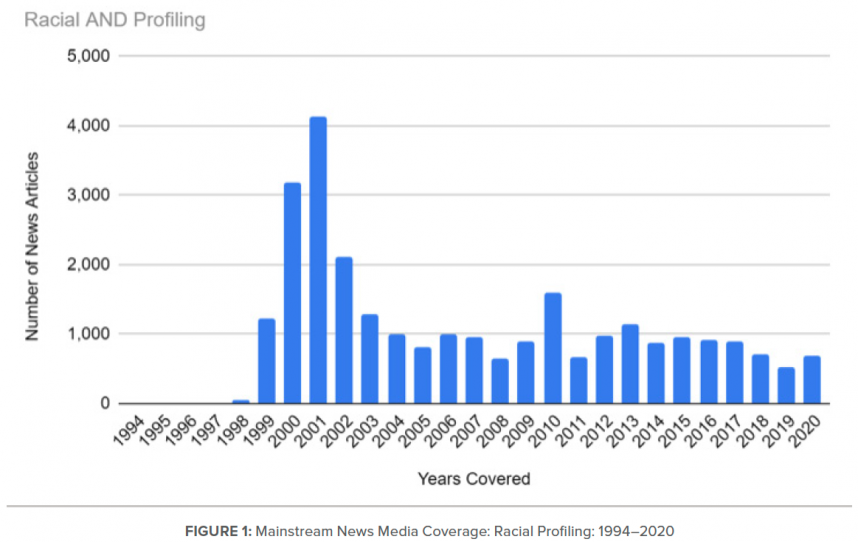

The release of these statistics generated more media coverage. The number of stories about racial profiling published in U.S. newspapers increased tenfold between 1998 and 1999. Calls for action were coming from civil rights and civil liberties organizations and African American elected leaders as complaints from their constituents poured in. At community meetings and legislative hearings around the country, racial profiling victims were testifying, oftentimes in tears, about their experiences. The New Jersey Legislative Black and Latino Caucus, for example, held three regional public hearings in April 1999 and concluded:

The testimony and other evidence adduced at the Caucus hearings confirmed what minority motorists have known for years—racial profiling has long been the ‘unofficial’ modus operandi of the State Police. The State Police hierarchy has unofficially encouraged, condoned and rewarded the practice. Reverend Reginald Jackson, Executive Director of the Black Ministers Council of New Jersey explained the situation in stark terms: ‘Racial profiling was the worst kept secret in New Jersey.’

The New Jersey hearings were closely followed by the media, and headlines served to frame the issue:

- “Hearing probes trooper racism,” Asbury Park Press, April 14, 1999

- “In Hearing, Blacks Tell of Stops by Troopers; Legislators Examine Profiling Complaints,” The Record (Bergen County), April 14, 1999

- “Minorities describe humiliation by State Police,” The Star-Ledger (Newark, New Jersey), April 14, 1999

At the federal level, Rep. John Conyers, Jr. (D-MI) introduced the Traffic Stops Statistics Act, which would have required that police departments collect demographic data on each traffic stop and that the U.S. Attorney General then conduct a study based on the data. It passed the House in 1998 without a single dissenting vote, but it died in the Senate.[3]

In the meantime, pushback from the police establishment was increasing. In a much-quoted statement, the superintendent of the New Jersey State Police, then under scrutiny by the courts and the state legislature, opined, “The drug problem is mostly cocaine and marijuana. It is most likely a minority group that’s involved with that.” In the fall of 1998, Attorney General Janet Reno held a national summit on the problem of race and traffic stops. In addition to local, state, and federal law enforcement representatives and U.S. attorneys from around the country, several advocacy organizations, including the National Urban League and the ACLU, were in attendance. Those from law enforcement struck a defensive tone according to one of the participants, claiming: “There is no such thing as racial profiling. It doesn’t exist. Collection of data on traffic stops that tracked race would be unnecessary and dangerous and an insult to every person who wore a badge. Merely raising the issue was a slap in the face to the brave officers who risked their lives to keep the peace.”[4]

All the lawsuits, hearings, and media coverage were still not producing the kind of policy changes that were needed. Every hour of every day, motorists of color were still being stopped; searched; and, in some cases, traumatized on the nation’s roads and highways. More had to be done. As frustration mounted, the ACLU decided to escalate its campaign.

THE ACLU’S CAMPAIGN AGAINST RACIAL PROFILING

The ACLU’s first challenge to racial profiling had been in the form of a class-action lawsuit against the Maryland State Police (MSP) on behalf of Robert L. Wilkins, an African American attorney who was stopped, detained, and searched in 1992 while driving to Washington, D.C., from Chicago. When he refused to consent to a search, the police told him, “You’re gonna have to wait here for the dog.” Wilkins and the other members of his family who were passengers were forced to get out of the car and stand in the dark and the rain by the side of the highway until the canine patrol arrived and confirmed there were no drugs in the car. The case was settled in 1993 and the settlement decree included a requirement that the state monitor highway searches for any pattern of discrimination. Three years later, the data showed that the MSP was still engaging in racial profiling. In his report to the court, statistician John Lamberth concluded:

While no one can know the motivations of each individual trooper in conducting a traffic stop, the statistics presented herein, representing a broad and detailed sample of highly appropriate data, show without question a racially discriminatory impact on blacks and other minority motorists from state police behavior along I-95.

Other lawsuits followed, and as the cases mounted, the ACLU’s National Legal Department assigned one of its staff attorneys to work with the organization’s fifty-plus state affiliates to generate more cases.

In February 1999 the ACLU of Northern California launched its Driving While Black or Brown campaign. Under the direction of staff attorney Michelle Alexander and communications director Elaine Elinson, it “aimed to inspire a shift in public consciousness on race and criminal justice.” The campaign established a “DWB Hotline” and aggressively publicized the stories it received. It held press conferences so that people who had called the hotline could speak directly to the media. It put up fifty billboards in African American and Latino neighborhoods advertising the campaign and the hotline and it produced several radio ads that dramatized the experience of being unfairly pulled over by the police. All this activity succeeded in growing a coalition that included civil rights and civic and faith organizations. According to Alexander and Elinson:

In many respects, the campaign was a greater success than we ever hoped or imagined. When the campaign began, the terms ‘racial profiling’ or ‘DWB’ were not widely used, and the problems associated with those practices were not part of the political discourse. At the peak of the campaign, those terms, and the problems they represented, permeated the political discourse in communities of all color in California and nationwide. Thousands of people participated in grassroots organizing efforts. Personal stories of racial profiling filled the airwaves.[6]

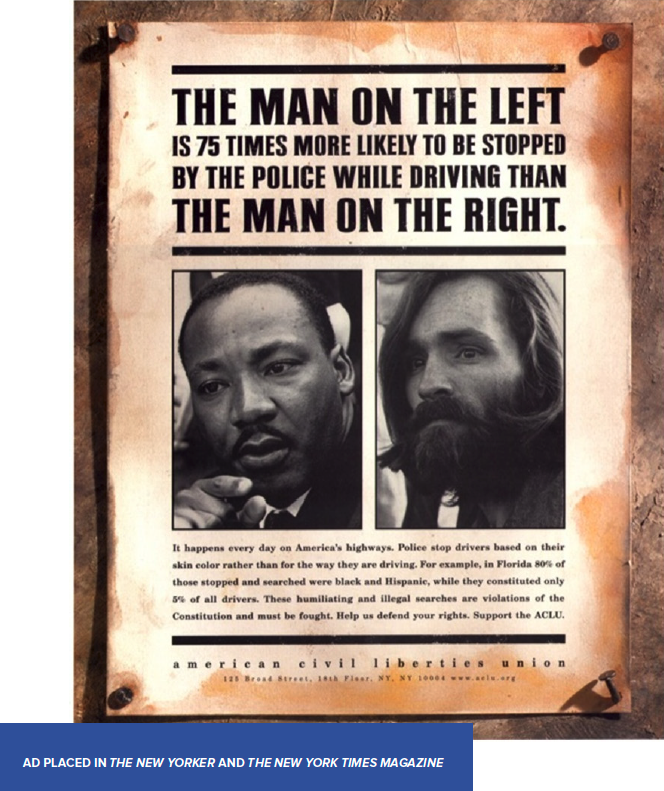

The national ACLU decided to adopt the Northern California affiliate’s model. On June 2, 1999 the organization held a press conference at its headquarters in New York City to announce the launch of a new national campaign. “We are here today to demand an end to racial profiling. The ACLU is using all of its available legal resources as well as advertising, public service announcements, statistical reports and yes, the media, to get our message out. Racial profiling of minority motorists is restoring Jim Crow justice in America,” said Executive Director Ira Glasser. The press conference was the occasion for the release of a 43-page report, “Driving While Black: Racial Profiling on Our Nation’s Highways.” Authored by David A. Harris, then a Professor of Law at the University of Toledo College of Law, the report linked the increase in racial profiling to the war on drugs and articulated the narrative that the ACLU was committed to “getting out”:

From the outset, the war on drugs has in fact been a war on people and their constitutional rights, with African Americans, Latinos and other minorities bearing the brunt of the damage. It is a war that has, among other depredations, spawned racist profiles of supposed drug couriers. On our nation’s highways today, police ostensibly looking for drug criminals routinely stop drivers based on the color of their skin. This practice is so common that the minority community has given it the derisive term, ‘driving while black or brown’—a play on the real offense of ‘driving while intoxicated.’

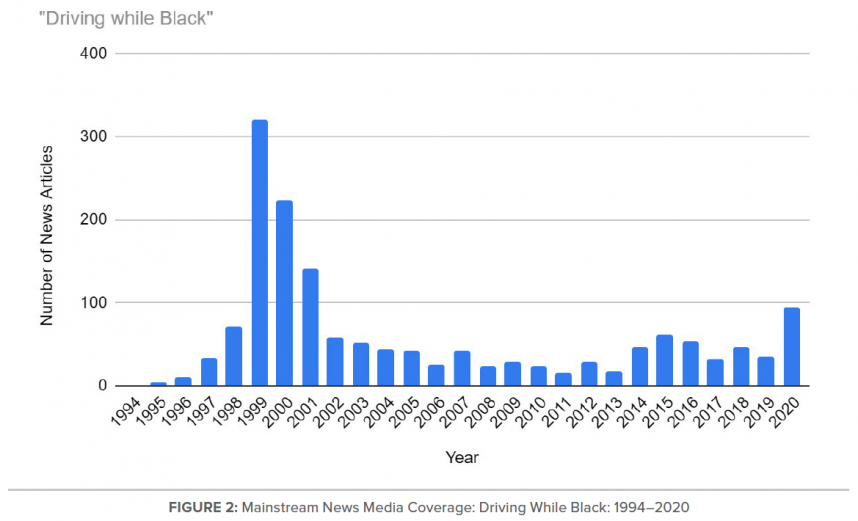

The announcement and the report received widespread media coverage, with articles referring specifically to “driving while Black” increasing from just 72 articles in 1998 to more than 300 in 1999.

Some of the headlines that clearly named the problem included:

- “Racial Profiling is Rising Nationwide, an ACLU Study Reports the ‘War on Drugs’ Targets Minorities, it says. Among its Suggestions: That Police Keep Better Data on Traffic Stops,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, June 3, 1999

- “ACLU report blasts racial profiling,” The Boston Globe, June 3, 1999

- “ACLU seeks end to racial profiling,” The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, June 2, 1999

- “Racial Profiling in Drug War Like Jim Crow: ACLU,” New York Daily News, June 3, 1999

The ACLU’s strategy was based on the adage that “sunlight is the best disinfectant.”[7] People would oppose injustice if only they knew about it. Glasser explains:

Racial profiling on our highways had long been a secret kept from most Americans and virtually from all white Americans. But it was never a secret to its victims…. And so it became important to us at the ACLU to spread this news around. It became our mission and our agenda to gather the information as systematically as we could and to make it as widely known as we could.

A nationwide toll-free hotline was established (1-877-6-PROFILE) for victims to call, and a complaint form was featured on the ACLU’s website. A full-page ad was placed in Emerge, then a popular magazine for Black audiences, and a public service announcement publicizing the hotline aired on Black radio stations nationwide. A “Driving While Black or Brown” kit composed of a sample letter to members of Congress in support of the Traffic Stops Statistics Act, stickers with the hotline number, and the ACLU’s so-called “bust card” explaining what to do if stopped by the police, was distributed in the tens of thousands. The organization’s Public Education Department kept up a steady stream of press releases and backgrounders for reporters and placed speakers, including victims of racial profiling, at conferences and on TV and radio broadcasts. Its Washington Legislative Office provided testimony and worked with the Congressional Black Caucus to drum up support for federal legislation. Its state affiliates worked with their allies, including the NAACP, the Urban League, and Black police organizations to generate support for state legislation and to pressure law enforcement agencies to collect data on a voluntary basis. It was all hands on deck.

Because the ACLU had offices in every state, the organization was able to generate activity on multiple fronts. Community speak-outs with journalists in attendance were held to give voice to victims of racial profiling. Advocates representing state and local civil rights coalitions engaged in public speaking and appeared in radio and television broadcasts and called for concrete action. The first step was to enact laws requiring the collection of data to establish that racial profiling was taking place. Once established, advocates would then lobby for legislation to ban it. The first state to pass legislation requiring data collection was North Carolina, with the ACLU of North Carolina working closely with the state legislature’s Black Caucus. Other states followed suit with substantial editorial support from all regions of the country:

- “An end to profiling,” The Courier-Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), April 23, 2000

- “State must do what it can to stop racial profiling,” The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, October 18, 1999

- “Racial profiling real and should cease,” San Antonio Express News, June 20, 1999

- “Stop Racial Profiling,” St. Petersburg Times (Florida), December 23, 2000

- “Act Now on Racial Profiling,” The San Francisco Chronicle, January 19, 2000

By any measure, the campaign was impactful. A week after the initial press conference and release of the Harris report in June 1999, President Bill Clinton declared that racial profiling was “morally indefensible” and ordered federal law-enforcement agencies to compile data on the race and ethnicity of people they question, search, or arrest to determine whether suspects were being stopped because of the color of their skin. A Gallup poll released in December 1999 revealed that 59 percent of the public believed that racial profiling was widespread, and 81 percent disapproved of its use by police. In 1999 alone, fifteen states considered legislation mandating the collection of traffic-stop information and, ultimately, twenty-nine of the forty-nine state police agencies with patrol duties would require the collection of race and ethnicity data.[8] Media coverage increased dramatically over the course of the campaign, from 2,741 stories in 1999 to close to 9,000 stories in 2001. In his February 27, 2001 address to a Joint Session of Congress, newly elected President George W. Bush declared that “racial profiling is wrong and we will end it in America.”

But the campaign’s most profound impact was its disruption of a deeply entrenched American narrative—what Ta-Nehisi Coates calls “the enduring myth of Black criminality.”

THE MYTH OF BLACK CRIMINALITY

Negative stereotypes about Black people abound in America, and one of the oldest is the stereotype that they are violent and predisposed to crime. In his 2015 lengthy essay “The Black Family in the Age of Mass Incarceration” (published in The Atlantic magazine) Ta-Nehisi Coates avers that “Black people are the preeminent outlaws of the American imagination”:

Black criminality is literally written into the American Constitution—the Fugitive Slave Clause, in Article IV of that document…the crime of absconding was thought to be linked to other criminal inclinations…. Nearly a century and a half before the infamy of Willy Horton, a portrait emerged of Blacks as highly prone to criminality, and generally beyond the scope of rehabilitation.

Like other negative racial stereotypes, Black criminality has proven to be a long-lived feature of American culture. One scholar, writing in the Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, observes:

In American society, a prevalent representation of crime is that it is overwhelmingly committed by young Black men. Subsequently, the familiarity many Americans have with the image of a young Black male as a violent and menacing street thug is fueled and perpetuated by typifications everywhere. In fact, perceptions about the presumed racial identity of criminals may be so ingrained in public consciousness that race does not even need to be specifically mentioned for a connection to be made between the two because it seems that talking about crime is talking about race.[9]

The myth and stereotype of Black criminality was reinforced and magnified during the 1980s and ’90s when crack cocaine became a national obsession. The media depicted crack as a Black, inner-city phenomenon. Local and national news shows were rife with footage of police breaking down the doors of “crack houses” and of Black and Brown men and women being carted off in handcuffs. Time and Newsweek each devoted five cover stories to crack and the drug crisis in 1986 alone, and CBS aired 48 Hours on Crack Street, featuring Black drug dealers. In The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander writes:

Thousands of stories about the crack crisis flooded the airwaves and newsstands, and the stories had a clear racial subtext. The articles typically featured black ‘crack whores,’ ‘crack babies,’ and ‘gangbangers,’ reinforcing already prevalent racial stereotypes of black women as irresponsible, selfish ‘welfare queens,’ and black men as ‘predators’—part of an inferior and criminal subculture.[10]

Intensified street-level enforcement of the drug laws in low-income communities of color filled the jails and prisons with Black and brown people, further reifying the myth of Black criminality. Politicians, eager to prove their anti-crime bona fides, introduced and passed a raft of new drug laws, lengthening sentences and eliminating parole. By 1994, more Americans named crime as “the most important problem facing this country today” than any other problem, and 85 percent of the public thought courts were not harsh enough. That year a bipartisan Congress would pass and President Clinton would sign the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, which incentivized states to enact mandatory sentencing laws and pumped close to $10 billion into new prison construction. That same year, the U.S. Justice Department announced that the prison population topped 1 million for the first time in U.S. history. What has come to be known as “mass incarceration” was well underway.

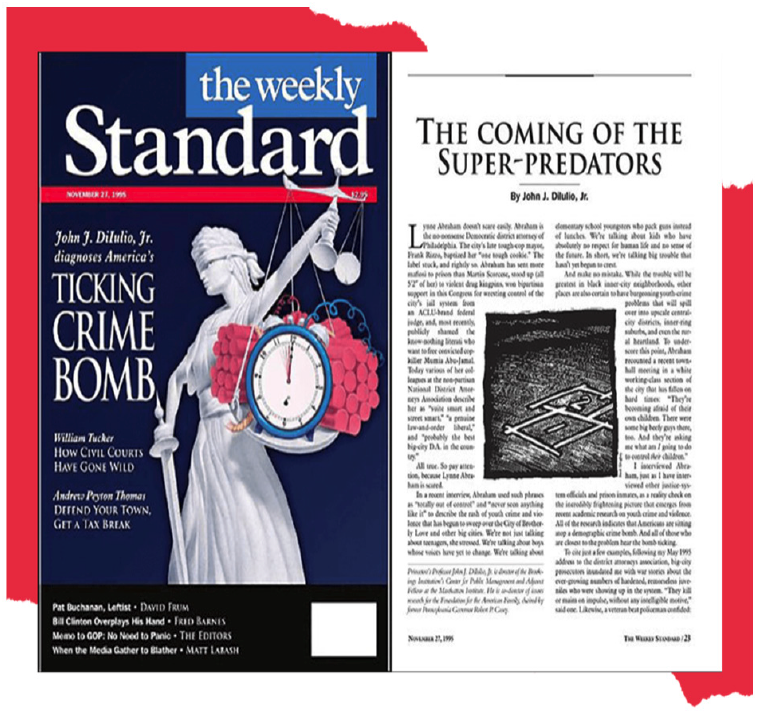

Then, in 1995, the myth received another boost. In November of that year, Princeton political scientist John DiLulio published an essay that would receive enormous media attention. Titled “The Coming of the Super-Predator” and appearing in The Weekly Standard, a then new conservative magazine, DiLulio darkly warned that like a contagion, Black criminality would spread beyond the ghetto and into “even the rural heartland”:

We’re not just talking about teenagers. We’re talking about boys whose voices have yet to change. We’re talking about elementary school youngsters who pack guns instead of lunches. We’re talking about kids who have absolutely no respect for human life and no sense of the future. In short, we’re talking big trouble that hasn’t yet begun to crest. And make no mistake. While the trouble will be greatest in black inner-city neighborhoods, other places are also certain to have burgeoning youth-crime problems that will spill over into upscale central-city districts, inner-ring suburbs, and even the rural heartland.

The term was quickly adopted by the media; researchers found nearly 300 uses of the word “super-predator” in forty leading newspapers and magazines from 1995 to 2000.[11] Those researchers point out that just a few years before, the news media had introduced the terms “wilding” and “wolf pack” to the national vocabulary, to describe five teenagers—four Black and one Latino— who were convicted and later exonerated of the rape of a woman in New York’s Central Park. This incident incited sensationalist coverage that declared the teenagers guilty before trial and led then hotel mogul Donald Trump to call for their execution. Kim Taylor-Thompson, a law professor at New York University, noted: “This kind of animal imagery was already in the conversation. The super-predator language began a process of allowing us to suspend our feelings of empathy towards young people of color.”

This was the political and cultural environment in which the ACLU and its allies sought to build public opposition to racial profiling. Racial profiling and the myth of black criminality were, and are, inextricably intertwined. By focusing on how a system preyed upon the innocent, the campaign to end racial profiling disrupted the myth and complicated things, allowing a new narrative about race and criminal justice to emerge. The mistreatment of Black people by law enforcement was not a matter of a few bad apples among the police; it was a matter of policy decisions that were made by those in authority. In spite of a deluge of dog whistles and overtly racialized media coverage linking criminality with Black people, a very substantial majority of Americans—81 percent according to the Gallup poll—did not want the police to target people based on skin color. Racial profiling was wrong.

CAMPAIGN INTERRUPTED

In August 2001 hearings were held before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary concerning the End Racial Profiling Act of 2001. The Act, which was sponsored by Sen. Russ Feingold (D-WI) and Rep. Conyers and had bipartisan sponsors from both chambers, had been hammered out with input from civil rights and civil liberties advocates as well as law enforcement experts and practitioners. It would have required federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies to take steps to cease and prevent the practice, including implementing effective complaint procedures and disciplinary procedures for officers who engaged in the practice.[12] In his welcoming remarks, Sen. Feingold said, “Racial profiling is a shame on our society that must be stopped. It is unjust. It is un-American.” He noted that, “There is an emerging consensus in America that racial profiling is wrong and should be brought to an end” and emphasized the profound harms it caused to African Americans:

I have also heard from African American parents that they feel they must do something that would not even cross the minds of white parents: instruct their children from a very early age about the prospect and even likelihood of being stopped by the police when they haven’t done anything wrong. That to me is a chilling fact. Racial profiling leads to our children being taught from an early age, as a matter of self-protection, that they will not be fairly treated by law enforcement based on the content of their character, but instead will be seen as suspicious based on the color of their skin.[13]

By September 10 headlines indicated that the Act and various efforts around the country to bring racial profiling under control were underway and still had considerable media traction:

- “NJ kicks off two-day summit on racial profiling,” The Associated Press, September 10, 2001

- “Racial Profiling New Police Policy is a Good Step Toward Ending Abusive Practice,” Editorial, The Post-Standard (Syracuse, NY), September 10, 2001

- “Justice Dept. to begin nationwide study of racial profiling with voluntary participation by police,” The Associated Press, September 10, 2001

- “Forum on Racial Profiling Aims to Ask Questions,” The Virginian-Pilot (Norfolk, VA), September 10, 2001

- “Officials answer racial profiling questions at NAACP event,” The Kansas City Star, September 10, 2001

Then 9/11 happened.

The events of 9/11 and its aftermath stymied the campaign to end racial profiling. The new narrative—that racial profiling was systemic, wrong, unconstitutional, and un-American—was not yet strong enough or capacious enough to resist the calls for the widespread ethnic profiling that was a key feature of the domestic “war on terror.” In a white paper published by The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, the country’s largest and most diverse civil rights coalition deplored the breakdown of a “national consensus against racial profiling”:

In the months preceding September 11, 2001, a national consensus had developed on the need to end racial profiling. The enactment of a comprehensive federal statute banning the practice seemed imminent. However, on 9/11, everything changed. In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks, the federal government focused massive investigatory resources on Arabs and Muslims, singling them out for questioning, detention, and other law enforcement activities. Many of these counterterrorism initiatives involved racial profiling.[14]

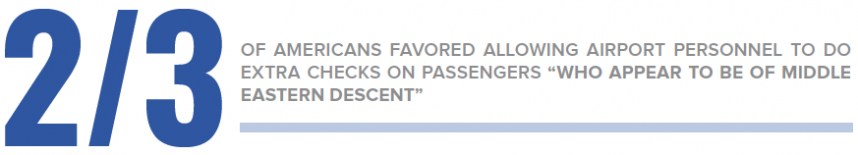

Ethnic profiling, by both law enforcement and the general public, would go on for years, and although it was challenged in numerous lawsuits and criticized by a broad coalition that included leaders representing the gamut of religious faiths, most Americans accepted it as a necessary tool to prevent new acts of terrorism. On the 1-year anniversary of the attack, the Pew Research Center conducted a survey and found that two-thirds of Americans favored allowing airport personnel to do extra checks on passengers “who appear to be of Middle-Eastern descent.”[15]

The national debate over immigration, which reached a.crescendo in the spring of 2007 when the U.S. Senate was considering the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act, further weakened the nation’s commitment to end racial and ethnic profiling. The Act, which had the support of President Bush during his final year in office, would have provided legal status and a path to citizenship for the approximately 12 million undocumented immigrants. In spite of the fact that public opinion surveys showed substantial support for comprehensive reform, the anti-immigrant movement led by media personalities such as Rush Limbaugh and Bill O’Reilly mobilized followers to inundate the Senate with anti-reform mail and the Act was shelved.

In this increasingly hostile political environment, the ethnic profiling of suspected “illegal aliens” reached new heights in 2010 with Arizona’s passage of the Support Our Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhoods Act (SB 1070). The law sanctioned profiling by requiring state law enforcement officers to determine an individual’s immigration status during a “lawful stop, detention or arrest” when there was “reasonable suspicion that the individual is an illegal immigrant.” The law was immediately denounced by immigrants’ rights organizations and their allies and several lawsuits were quickly filed, including one by the U.S. Department of Justice, challenging the law’s constitutionality. But polls taken during the controversy showed that a majority of Americans supported the law, including 70 percent of Arizona voters.

It is fair to say that during the first decade of the twenty-first century, the nation’s commitment to ending racial profiling was in retreat. The issue did not disappear, and flare-ups such as the arrest of Henry Louis Gates as he entered his own home and the subsequent “beer summit” held by President Obama continued to draw headlines. But the narrative that had propelled so much discussion, protest, and policy advocacy during the period leading up to 9/11 had lost its urgency as the public discourse shifted its focus to national security, immigration, and other hot button issues.

Most of the laws passed by states mandating the collection of data stayed in effect for just 2 or 3 years as their purpose was to determine whether law enforcement was engaging in racial profiling. In most instances, the data were never even analyzed, and when they were, few meaningful steps were taken to address the racial disparities that were found.[16] North Carolina, which was the very first state to enact a data collection law, had accumulated data on 20 million traffic stops before an analysis was finally undertaken by three academics in 2015.[17] Although it was reintroduced year after year by Rep. Conyers, the End Racial and Religious Profiling Act was never passed. By 2011, when The Leadership Conference issued its white paper urging the restoration of a “national consensus” to end racial profiling and the passage of The End Racial Profiling Act (of 2010), the campaign was sputtering.

CAMPAIGN REENERGIZED

In early 2012, a tragedy rekindled the campaign to end racial profiling. On the night of February 26, Trayvon Martin, an unarmed 17-year-old African American high school student, was followed, shot, and killed by self-styled neighborhood watchman George Zimmerman in Sanford, Florida. Protests erupted nationwide as the police initially declined to arrest Zimmerman. From the start, Martin was said to be a victim of racial profiling—a young Black man wearing a hoodie and walking alone in a gated community. The myth of Black criminality was never far from the surface in such scenarios. At a demonstration at the state capitol in Tallahassee 3 weeks after the killing protesters called for a task force to be formed to address racial profiling: “Trayvon Martin is dead because of racial profiling,” one of the organizers said. “We all deal with it every single day and we want the governor to pay attention to that.”[18] Finally, after weeks of nationwide “Justice for Trayvon” demonstrations and an announcement by the U.S. Justice Department of plans to investigate the killing, Zimmerman was charged with second-degree murder.

The case went to trial in June 2013 and received massive coverage in the media, and the issues of race and racial profiling were front and center. “Zimmerman and profiling go on trial,” read one headline in USA Today. A CNN reporter described it as the case that “sparked a protest and passionate debate about race and racial profiling.” So potent was the term “racial profiling” that the trial judge granted the defense’s request that it not be allowed and ruled that only the word “profiling” could be used by the prosecution. On July 13, 2013 the jury acquitted Zimmerman of all charges, provoking a nationwide outcry. Protests were held in more than 100 cities. In her statement following the verdict, Roslyn Brock, chairman of the NAACP said, “This case has re-energized the movement to end racial profiling in the United States.” And on July 14, Patrisse Cullors, an artist, author, and educator, reposted a message about the acquittal originally posted on Facebook by activist Alicia Garcia and used the hashtag #blacklivesmatter for the first time.

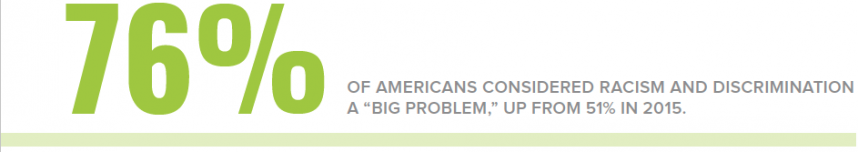

In the years since #blacklivesmatter went viral, the myth of Black criminality has been under siege and the narrative communicated by the original campaign against racial profiling—that it was systemic and based on anti-Black animus—has made enormous headway in the public discourse. A public opinion survey carried out by the Washington Post in June 2020 asked: “Do you think the killing of George Floyd was an isolated incident or is a sign of broader problems in treatment of black Americans by police?” 69 percent chose the latter explanation.[19] Another poll taken during the same period found that 76 percent of Americans considered racism and discrimination a “big problem,” up from 51 percent in 2015.[20] Brittany Packnett Cunningham, co-founder of Campaign Zero,[21] explains:

Six years ago, people were not using the phrase systemic racism beyond activist circles and academic circles. And now we are in a place where it is readily on people’s lips, where folks from CEOs to grandmothers up the street are talking about it, reading about it, researching on it, listening to conversations about it.[22]

Since its birth in 2014, the Black Lives Matter movement has, in essence, accomplished what the original ACLU campaign sought to accomplish: to expose a “secret kept from most Americans and virtually from all white Americans” and to “spread this news around”—but today with the benefit of the smartphone, police body cameras, and social media.

The ability to capture not only police interactions, but also ordinary or “casual” acts of profiling and discrimination carried out by white members of the public—for example, “shopping while Black,” “jogging while Black,” and “birdwatching while Black” —and then to share the videos via different social media platforms has accelerated the narrative shift in ways that would have seemed inconceivable in 1999. In September 2020 the Center for Technology Innovation at the Brookings Institution hosted a webinar on the role of technology in support of the Black Lives Matter Movement. Dr. Rashawn Ray, a sociologist and fellow at the Brookings Institution explained that he and a group of researchers have been “collecting and curating data on social media and the Black Lives Matter movement”:

We have a large digital archive of Tweets, starting in 2014 when Michael Brown was killed, and we’ve just continued to curate those data, millions and millions of Tweets…. The way that the movement for Black lives has been able to use social media is unprecedented. Let’s go back to five or six years ago. For Michael Brown, Freddie Gray, Sandra Bland, and so many others who weren’t so fortunate as to have a hashtag, the level of public support at that time was significantly lower. People were trying to figure out Black Lives Matter. But support for the Black Lives Matter movement has significantly increased in a short period of time because people affiliated with the movement have figured out how to use social media. They’ve particularly figured out how to use social media algorithms. So, part of what happened more recently with George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor is that whether people are using hashtags on Twitter, Instagram, SnapChat, or TikTok, the algorithm loads up additional videos for people to see to show that what happened to George Floyd is not isolated. That instead, it’s part of a broader pattern of systemic racism and police brutality. Not only that—the videos also show white people behaving in similar ways, but getting treated significantly differently than Black people. And I think that’s one of the biggest things. And it’s led to this racial awakening.”

PERMIT PATTYS, BBQ BECKYS, AND KARENS: THE EVOLUTION OF RACIAL PROFILING DISCOURSE ONLINE

As the Black Lives Matter movement propelled the issue of systemic racism into global public discourse, a smaller subsection of social media content has focused specifically on the everyday profiling of people of color. The so-named “Karen” video has become a regular trending topic on popular social media channels in recent years and points to an important shift in public understanding of the issue. The proliferation of smartphones has enabled people of color to capture not only instances of racial profiling carried out by the police and other government authorities, but also everyday instances of racism perpetrated by members of the general public.

While the exact origin of the term “Karen” (and the male equivalent “Ken”) remains a topic of debate, it is generally used to describe white women who behave in an entitled, rude, or authoritative way, usually toward people of color and other traditionally marginalized groups. Beginning as a pejorative, “Karen” has evolved into a catchall to describe a broader range of entitled behaviors (and even a hairstyle), with “mask Karen” (white women caught on camera refusing to wear masks in public in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic) being the latest example of the evolution of the term. As noted by journalist Helen Lewis in her piece on the development of the term and its link to a longer history of racism and sexism in America:

One phrase above all has come to encapsulate the essence of a Karen: She is the kind of woman who asks to speak to the manager. In doing so, Karen is causing trouble for others. It is taken as read that her complaint is bogus, or at least disproportionate to the vigor with which she pursues it. The target of Karen’s entitled anger is typically presumed to be a racial minority or a working-class person, and so she is executing a covert maneuver: using her white femininity to present herself as a victim, when she is really the aggressor.[23]

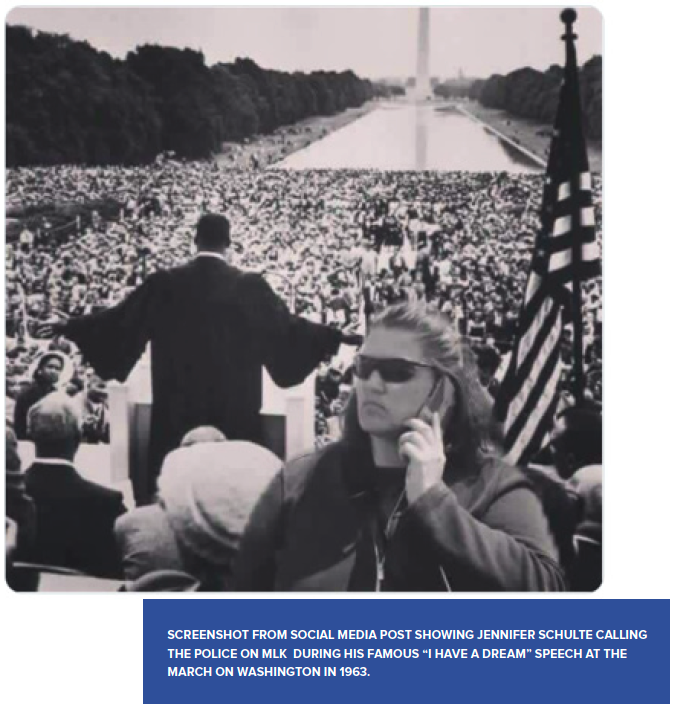

The genesis of the “Karen” video and its connection to wider narratives about racial profiling are visible in social media and traditional news media. References to “Permit Patty” and “BBQ Becky” first emerged in news media coverage in 2018 as a result of several viral videos depicting Black people being confronted by white women for engaging in everyday activities. One of most widely shared videos was uploaded in April 2018 and captured Jennifer Schulte, later dubbed “BBQ Becky,” calling the police on two Black men for the offense of using a charcoal grill in a designated grilling area in Lake Merritt Park in Oakland, California. The video of the encounter, which shows Schulte being questioned by a bystander for her decision to call the police, went viral and gave way to a surge of articles and “BBQ Becky” memes (often depicting Schulte calling the police on historical Black figures). Nearly 200 articles were published in mainstream news media in 2018 alone about Jennifer Schulte and other individuals caught on video calling the police on Black people.

“Permit Patty” and “BBQ Becky” have been joined by dozens of other viral videos depicting Black people being questioned and threatened in public parks; swimming pools; or, at times, in their own apartment buildings. Between 2018 and 2020, nearly 500,000 unique social media posts were generated referring to “Karens,” “BBQ Becky,” and other popular variants. At the same time, just over 3,700 news media articles have been published on the phenomena, with some of the headlines including:

- “BBQ Becky, White Woman Who Called Cops on Black BBQ, 911 Audio Released: ‘I’m Really Scared! Come Quick!’,” Newsweek, September 4, 2018

- “What exactly is a ‘Karen’ and where did the meme come from?” BBC News, July 30, 2020

- “A Brief History of Karen,” New York Times, July 31, 2020

- “The Mythology of Karen: The meme is so powerful because of the awkward status of white women,” The Atlantic, August 24, 2020

The most recent video to go viral featured Amy Cooper in Central Park calling the police on birdwatcher Christian Cooper after he requested that she put her dog on a leash. Amy Cooper was subsequently charged with filing a false police report following widespread media coverage of the encounter. Her case was dismissed after she completed therapeutic and educational programs on racial justice.

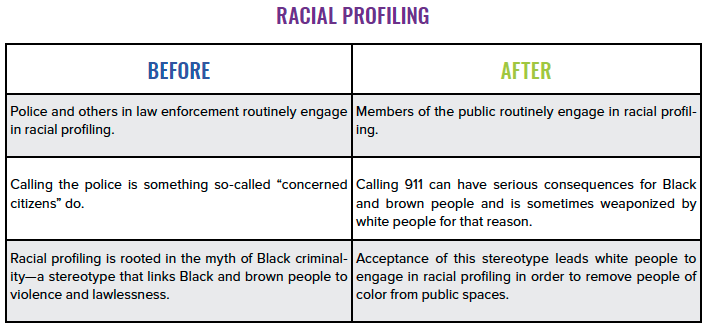

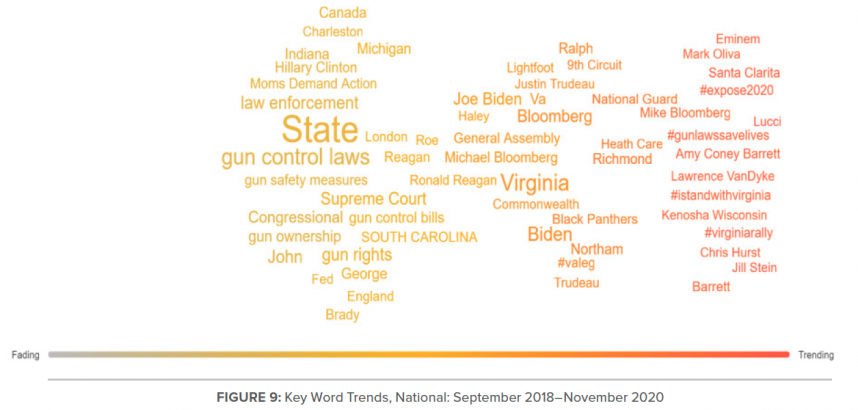

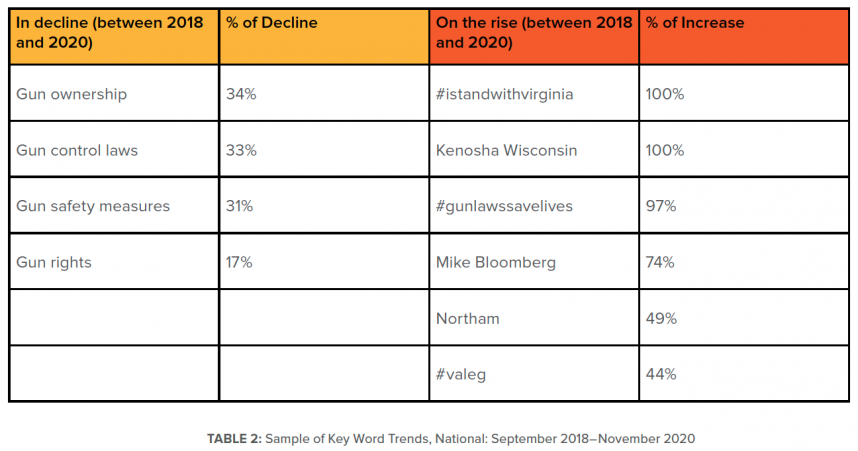

Beyond providing a space for Black and brown Americans to document their experiences and uplift the casual and, at times, absurd manifestations of racism, “Karen” videos have resulted in several municipalities across the country passing or proposing ordinances to tackle the issues of discriminatory 911 calls. The CAREN Act (Caution Against Racially Exploitative Non-Emergencies) introduced by Shamann Walton, a member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, is just one example of such measures. While online discussion of racial profiling remains overwhelmingly focused on law enforcement, an exploration of trending topics associated with racial profiling since 2018 reveals an important shift in the framing of the issue and a 98 percent increase in references to the “consequences” of racial profiling. Other notable shifts include the following:

CONCLUSION

In her book Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, Isabel Wilkerson shows how America, now and throughout its history, has been shaped by a hidden caste system in which Black people occupy the lowest rung. She compares America to an old house in which signs of deterioration may not be visible. You may not want to investigate “what is behind this discolored patch of brick,” but “choose not to look at your own peril.” She writes, “You cannot fix a problem until and unless you can see it.” Profiling is, and has always been, one of the many tools used to maintain systemic discrimination in our country and to keep Black people “in their place.”

Racial progress in this country has been a maddeningly slow process punctuated by periods of upheaval. Decades can pass without real change, causing conditions to worsen, and then events occur that bring the festering problem into the light. Such was the televised spectacle of fire hoses and dogs being turned on nonviolent protesters in the South in the 1960s, the vicious beating of Rodney King by Los Angeles police officers in 1991, and the murder of George Floyd in 2020. The Black Lives Matter movement is carrying the campaign to end racial profiling forward by exposing its ubiquity and its dire consequences. Surveys taken in June 2020 during the massive protests following George Floyd’s murder showed that a majority of white adults supported the movement.[24] And the participation of tens of thousands of white people in protests throughout the nation was unprecedented. Along with exposure comes narrative shift. Racial profiling is real, it is wrong, and it must end.

1 A Gallup poll released on December 9, 1999 showed that 59 percent of the public believed racial profiling was widespread, and an overwhelming 81 percent disapproved of its use by police.

2 David A. Harris, “When Success Breeds Attack: The Coming Backlash Against Racial Profiling Studies,” Michigan Journal of Race and Law, V. 6, 2001:237.

3 In August 2001, the End Racial Profiling Act was introduced in both houses but did not pass. The Act has been reintroduced virtually every year since.

4 Harris, p. 108

5 Wilkins is now a federal judge serving on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia.

6 Alexander and Elinson, unpublished manuscript.

7 Justice Louis Brandeis.

8 Bureau of Justice Statistics Fact Sheet: “Traffic Stop Data Collection Policies for State Police, 2004.”

9 Kelly Welch, “Black Criminal Stereotypes and Racial Profiling,” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, Vol. 23, August 2007.

10 P. 52

11 Carroll Bogert and Lynnell Hancock, “Superpredator: The Media Myth that Demonized a Generation of Black Youth,” The Marshall Project, November 20, 2020.

12 The bill also conditioned certain federal funds to state and local law enforcement agencies on their compliance with these requirements and authorized the attorney general to provide incentive grants to assist agencies with their compliance with this Act. Finally, the bill would have required the attorney general to report to Congress 2 years after enactment of the Act and each year thereafter on racial profiling in the United States.

13 BANNING RACIAL PROFILING, Federal Document Clearing House Congressional Testimony, August 1, 2001, Wednesday.

14 “Restoring a National Consensus: The Need to End Racial Profiling in America,” The Leadership Conference, March 2011.

16 David A. Harris, “Racial Profiling: Past, Present, and Future?” American Bar Association, January 21, 2020.

17 Frank R. Baumgartner, Derek A Epp, and Kelsey Shoub, Suspect Citizens: What 20 Million Traffic Stops Tell Us About Policing and Race. Cambridge University Press, 2018. The study’s conclusion: “When we look across all police agencies in the entire state, and no matter if we base our estimates of the population on census data or more refined estimates of who is driving, we see strong, consistent, and powerful evidence that black and white drivers face dramatically different odds of being pulled over.” P. 77.

18 Tallahassee Democrat.

20 https://www.monmouth.edu/polling-institute/reports/monmouthpoll_us_060220/

21 https://www.joincampaignzero.org/#campaign

22 Adam Serwer, “The New Reconstruction,” The Atlantic, October 2020 issue.

23 Helen Lewis, “The Mythology of Karen: The meme is so powerful because of the awkward status of white women,” The Atlantic, August 2020.

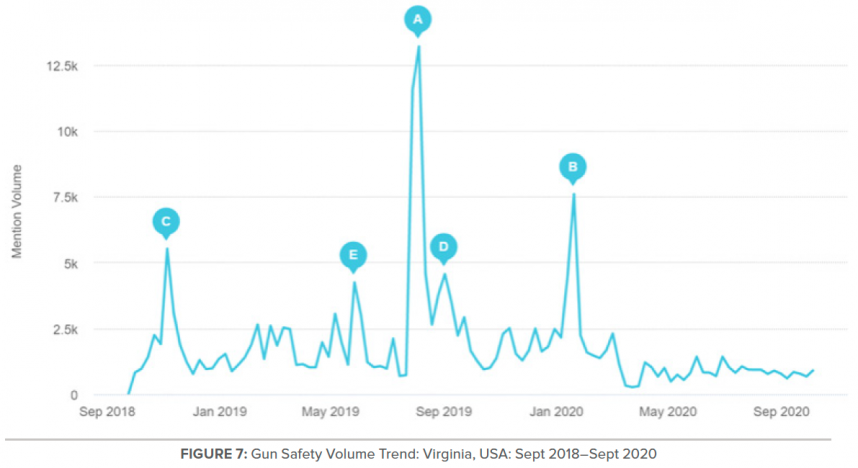

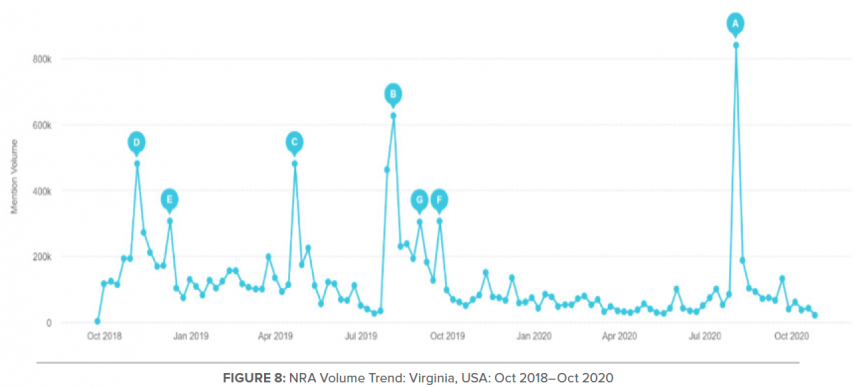

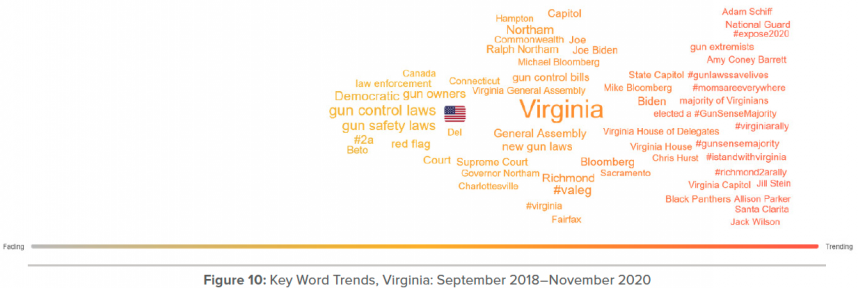

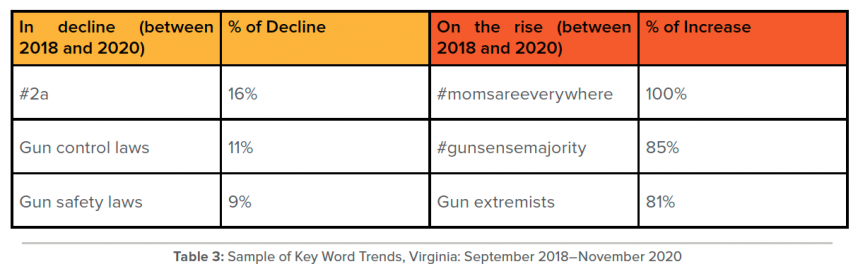

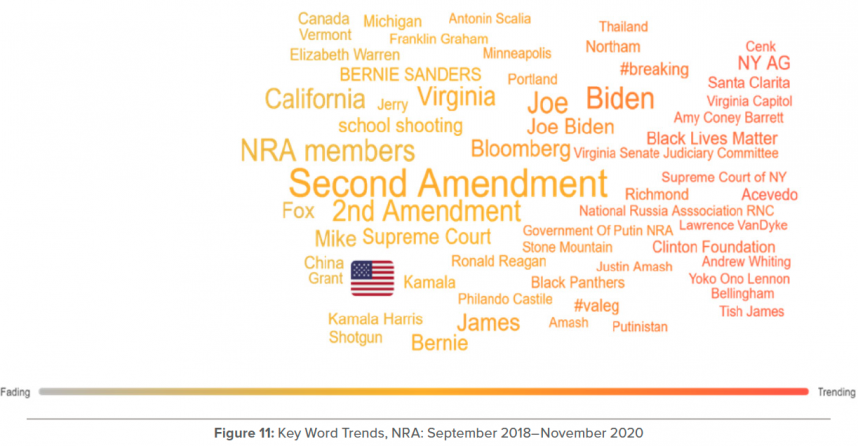

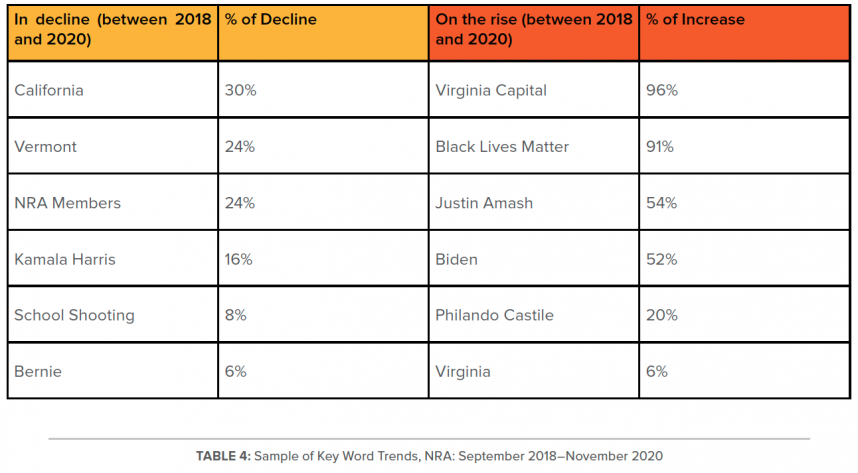

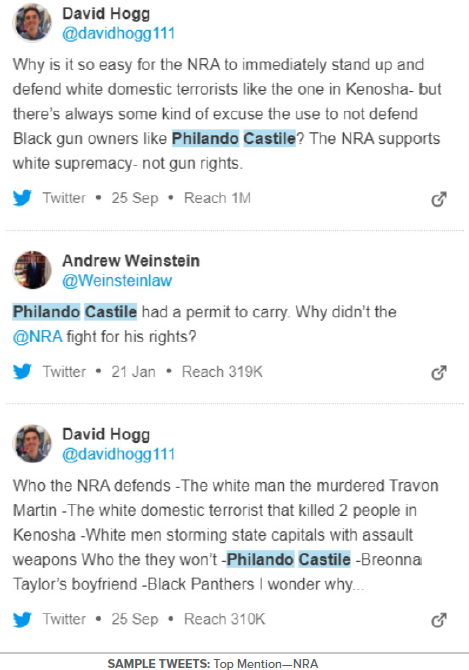

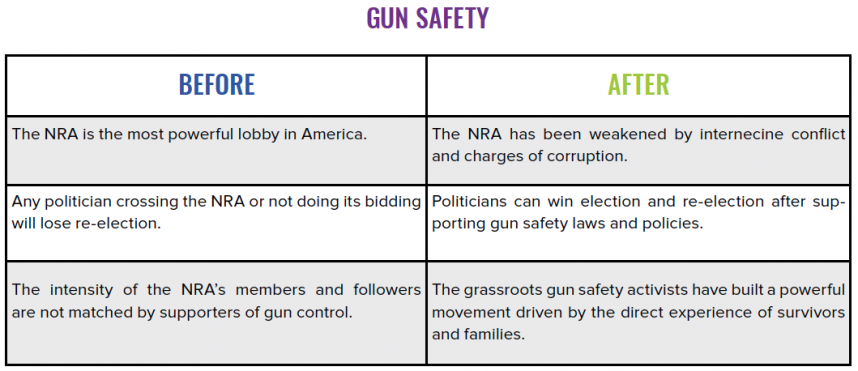

The 2017 gubernatorial election between Democrat Ralph Northam and Republican Ed Gillespie amounted to a state referendum on guns, with Michael Bloomberg and the Everytown for Gun Safety Action Fund contributing close to $2 million to elect Northam and his two running mates, Mark Herring for attorney general and Justin Fairfax for lieutenant governor. In the midst of the campaign, a shooter fired 1,000 rounds of ammunition on the crowd attending a music festival in Las Vegas, killing sixty people and wounding more than 400. A New York Times article was published several days later with the headline, “In Virginia, Gun Control Heats Up the Governor’s Race,” and the candidate’s dueling responses captured the partisan divide on the issue. Northam argued, “We as a society need to stand up and say it is time to take action. It’s time to stop talking.” Gillespie, who touted his “A” rating from the NRA, said it was “too early to discuss policy responses to gun violence.” In November Northam defeated Gillespie, winning by the largest margin for a Democrat in more than 30 years. On taking office in January 2018 Gov. Northam introduced several gun safety measures, but they failed in the Republican-controlled General Assembly. Then, on May 31, the Virginia Beach mass shooting happened, in which twelve people were killed at the city’s municipal center by a heavily armed lone gunman.

The 2017 gubernatorial election between Democrat Ralph Northam and Republican Ed Gillespie amounted to a state referendum on guns, with Michael Bloomberg and the Everytown for Gun Safety Action Fund contributing close to $2 million to elect Northam and his two running mates, Mark Herring for attorney general and Justin Fairfax for lieutenant governor. In the midst of the campaign, a shooter fired 1,000 rounds of ammunition on the crowd attending a music festival in Las Vegas, killing sixty people and wounding more than 400. A New York Times article was published several days later with the headline, “In Virginia, Gun Control Heats Up the Governor’s Race,” and the candidate’s dueling responses captured the partisan divide on the issue. Northam argued, “We as a society need to stand up and say it is time to take action. It’s time to stop talking.” Gillespie, who touted his “A” rating from the NRA, said it was “too early to discuss policy responses to gun violence.” In November Northam defeated Gillespie, winning by the largest margin for a Democrat in more than 30 years. On taking office in January 2018 Gov. Northam introduced several gun safety measures, but they failed in the Republican-controlled General Assembly. Then, on May 31, the Virginia Beach mass shooting happened, in which twelve people were killed at the city’s municipal center by a heavily armed lone gunman.

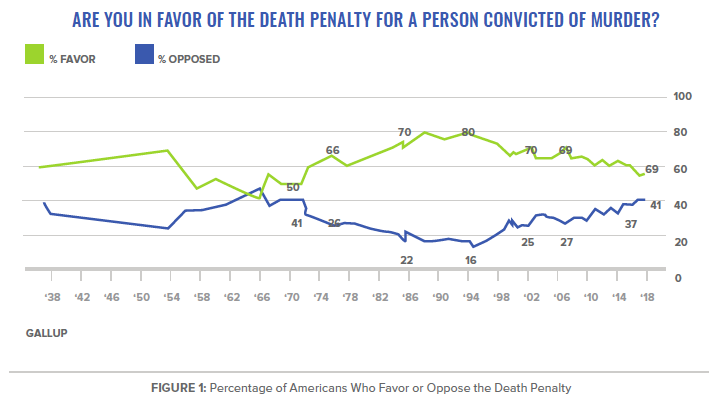

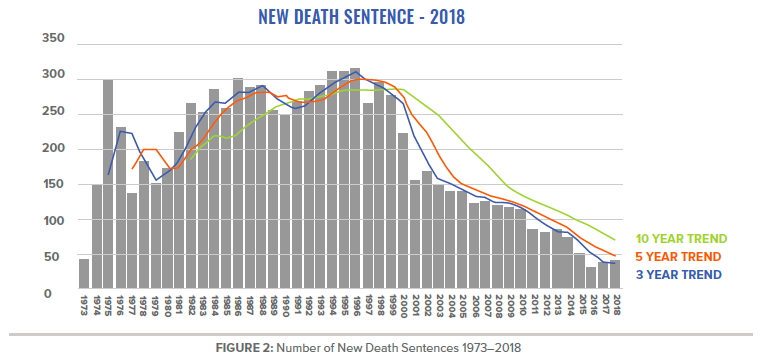

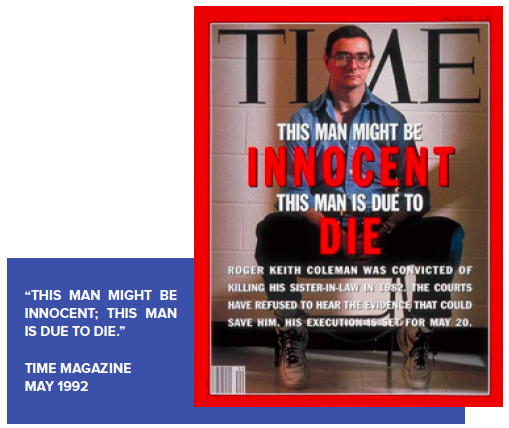

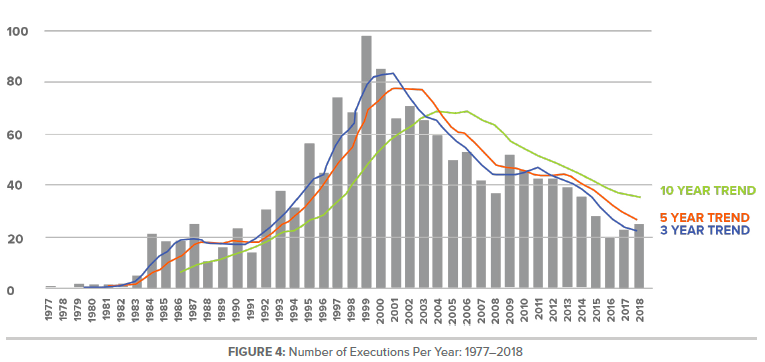

These recent policy reforms would not have been possible were it not for the erosion of public support for the death penalty. In the peak year of 1995, 80 percent of Americans supported the death penalty and only 16 percent opposed it for people convicted of murder. Today support for the death penalty is the lowest it has been in the past 40 years, with 56 percent in favor and 42 percent opposed. The decline in public support, in turn, is reflected in the imposition of fewer death sentences by juries. In 2018, 42 new death sentences were imposed as compared to 315 in 1996.

These recent policy reforms would not have been possible were it not for the erosion of public support for the death penalty. In the peak year of 1995, 80 percent of Americans supported the death penalty and only 16 percent opposed it for people convicted of murder. Today support for the death penalty is the lowest it has been in the past 40 years, with 56 percent in favor and 42 percent opposed. The decline in public support, in turn, is reflected in the imposition of fewer death sentences by juries. In 2018, 42 new death sentences were imposed as compared to 315 in 1996.

New voices entered the debate, most significantly family members of murder victims who opposed the death penalty, and Murder Victims’ Families for Human Rights was founded. Affiliates of the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty ramped up their efforts to expose the flaws in their states’ systems, issuing public reports and engaging in legislative advocacy and local media outreach. According to Diann Rust-Tierney:

New voices entered the debate, most significantly family members of murder victims who opposed the death penalty, and Murder Victims’ Families for Human Rights was founded. Affiliates of the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty ramped up their efforts to expose the flaws in their states’ systems, issuing public reports and engaging in legislative advocacy and local media outreach. According to Diann Rust-Tierney: