Updated July 2020

As we strive to improve conversations about race, racism, and racial justice in this country, the environment in which we’re speaking seems to be constantly shifting, which shows that these conversations are more important than ever. We’ve put together some advice on finding entry points based on research, experience, and the input of partners from around the country. This is by no means a complete list, but it is a starting point for moving these discussions forward.

Please note that while there are many reasons to communicate with various audiences about racial justice issues, this memo focuses on messaging with the primary goal of persuading them toward action. There are many times when people need to communicate their anger, frustration, and pain to the world and to speak truth to power. Doing so may not always be persuasive, but that obviously doesn’t make it any less important. Since we’re considering persuasion a priority goal in this memo, please consider the following advice through that lens.

1. Lead with Shared Values: Justice, Opportunity, Community, Equity

Starting with values that matter to your audience can help people to “hear” your messages more effectively than dry facts or emotional rhetoric would. Encouraging people to think about shared values encourages aspirational, hopeful thinking. When possible, this can be a better place to start when entering tough conversations than a place of fear or anxiety.

Sample Language:

Sample 1: To work for all of us, the people responsible for our justice system have to be resolute in their commitment to equal treatment and investigations based on evidence, not stereotypes or bias. But too often, police departments use racial profiling, which singles people out because of their race or accent, instead of evidence of wrongdoing. That’s against our national values, it endangers our young people, and it reduces public safety. We need to ensure that law enforcement officials are held to the constitutional standards we value as Americans—protecting public safety and the rights of all.

Sample 2: We’re a better country when we make sure everyone has a chance to meet their full potential. We say we’re a country founded on the ideals of opportunity and equality and we have a real responsibility to live up to those values. Discrimination based on race is contrary to our values and we need to do everything in our power to end it.

2. Use Values as a Bridge, Not a Bypass.

Opening conversations with shared values helps to emphasize society’s role in affording a fair chance to everyone. But starting conversations here does not mean avoiding discussions of race. We suggest bridging from shared values to the roles of racial equity and inclusion in fulfilling those values for all. Doing so can move audiences into a frame of mind that is more solution-oriented and less mired in skepticism about the continued existence of discrimination or our ability to do anything about it.

Sample Language:

It’s in our nation’s interest to ensure that everyone enjoys full and equal opportunity. But that’s not happening in our educational system today, where children of color face overcrowded classrooms, uncertified teachers, and excessive discipline far more often than their white peers. If we don’t attend to those inequalities while improving education for all children, we will never become the nation that we aspire to be.

Example:

A beautiful thing about this country is its multiracial character. But right now, we’ve got diversity with a lot of segregation and inequity. I want to see a truly inclusive society. I think we will always struggle as a country toward that—no post-racial society is possible or desirable—but every generation can make progress toward that goal. – Rinku Sen, Race Forward, to NBC News[1]

3. Know the Counter Narratives.

Some themes consistently emerge in conversations about race, particularly from those who do not want to talk about unequal opportunity or the existence of racism. While we all probably feel like we know these narratives inside out, it’s still important to examine them and particularly to watch how they evolve and change. The point in doing this is not to argue against each theme point by point, but to understand what stories are happening in people’s heads when we try to start a productive conversation. A few common themes include:

- The idea that racism is “largely” over or dying out over time.

- People of color are obsessed with race.

- Alleging discrimination is itself racist and divisive.

- Claiming discrimination is “playing the race card,” opportunistic, hypocritical demagoguery.

- Civil rights are a crutch for those who lack merit or drive.

- If we can address class inequality, racial inequity will take care of itself.

- Racism will always be with us, so it’s a waste of time to talk about it.

4. Talk About the Systemic Obstacles to Equal Opportunity and Equal Justice.

Too often our culture views social problems through an individual lens – what did a person do to “deserve” his or her specific condition or circumstance? But we know that history, policies, culture and many other factors beyond individual choices have gotten us to where we are today.

When we’re hoping to show the existence of discrimination or racism by pointing out racially unequal conditions, it’s particularly important to tell a full story that links cause (history) and effect (outcome). Without this important link, some audiences can walk away believing that our health care, criminal justice or educational systems work fine and therefore differing outcomes exist because BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and/or People of Color) are doing something wrong.

Example:

“The widely-discussed phenomenon of ‘driving while black’ illustrates the potential abuse of discretion by law enforcement. A two-year study of 13,566 officer-initiated traffic stops in a Midwestern city revealed that minority drivers were stopped at a higher rate than whites and were also searched for contraband at a higher rate than their white counterparts. Yet, officers were no more likely to find contraband on minority motorists than white motorists.” – The Sentencing Project publication, “Reducing Racial Disparity in the Criminal Justice System: A Manual for Policymakers”[2]

“Native Americans and Alaska Natives are often unable to vote because there are no polling places anywhere near them. Some communities, such as the Duck Valley Reservation in Nevada and the Goshute Reservation in Utah, are located more than 100 miles from the nearest polling place.” – Julian Brave NoiseCat, Native Issues Fellow at the Huffington Post[3]

5. Be Rigorously Solution-Oriented and Forward-Looking.

After laying the groundwork for how the problem has developed, it’s key to move quickly to solutions. Some people who understand that unequal opportunity exists may also believe that nothing can be done about it, leading to “compassion fatigue” and inaction. Wherever possible, link a description of the problem to a clear, positive solution and action, and point out who is responsible for taking that action.

Sample Language:

Sample 1: Asian Americans often face particularly steep obstacles to needed health care because of language and cultural barriers, as well as limited insurance coverage. Our Legislature can knock down these barriers by putting policies in place that train health professionals, provide English language learning programs, and organize community health centers.

Sample 2: The Department of Justice, Congress, local and state legislatures, and prosecutors’ offices should ensure that there is fairness in the prosecutorial decision-making process by requiring routine implicit bias training for prosecutors; routine review of data metrics to expose and address racial inequity; and the incorporation of racial impact review in performance review for individual prosecutors. DOJ should issue guidance to prosecutors on reducing the impact of implicit bias in prosecution.[4]

Example:

“Organizing to achieve public policy change is one major aspect of our larger mission to create freedom and justice for all Black people. Our aim is to equip young people with a clear set of public policy goals to organize towards and win in their local communities.” –BYP 100, “Agenda to Keep Us Safe,” website[5]

6. Consider Audience and Goals.

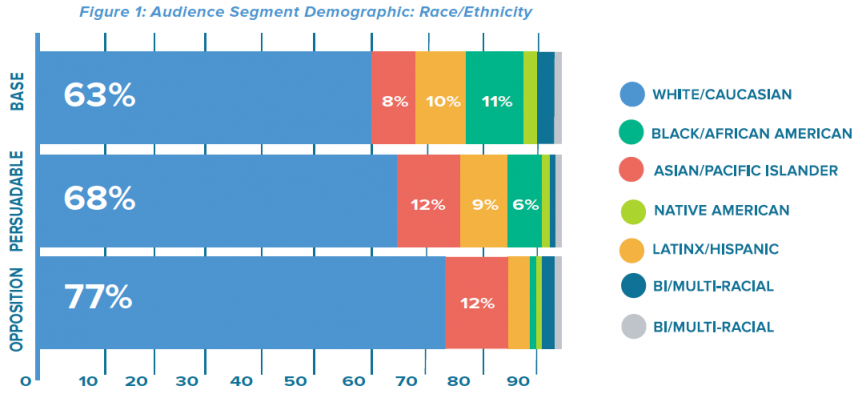

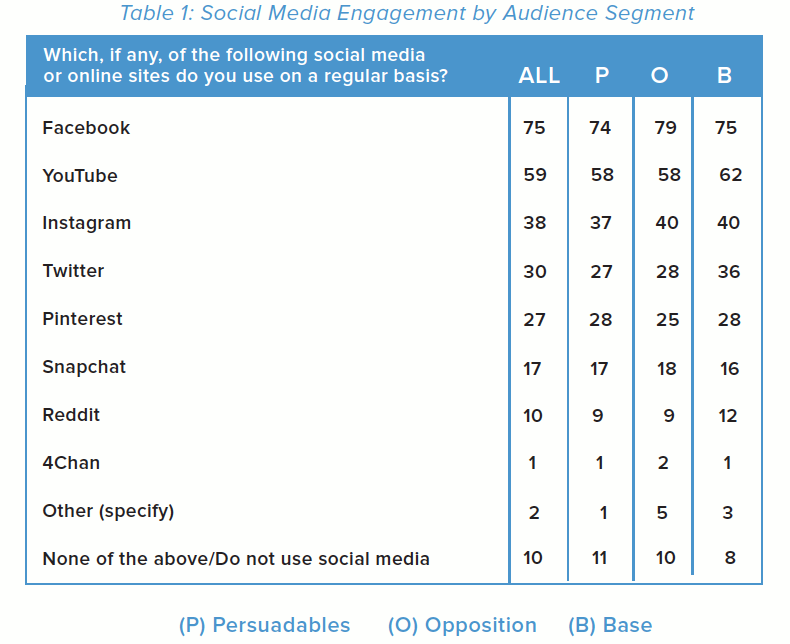

In any communications persuasion strategy, we should recognize that different audiences need different messages and different resources. In engaging on topics around race, racism, and racial justice, this is particularly important. We all know that people throughout the country are in very different places when it comes to their understanding of racial justice issues and their willingness to talk about them. While white people in particular need anti-racism resources and messaging that brings them into conversations about racism, there exists uncertainty or inexperience in other groups when it comes to talking about, for instance, anti-Black racism, stereotypes around indigenous communities, or anti-immigrant sentiments that are highly racialized. In strategizing about audience, the goal should be to both energize the base and persuade the undecided. A few questions to consider:

| Who are you hoping to influence? | Narrowing down your target audience helps to refine your strategy. |

| What do you want them to do? | Determine the appropriate action for your audience and strategy. Sometimes you may have direct access to decision makers and are working to change their minds. Other times you may have access to other people who influence the decision makers. |

| What do you know about their current thinking? | From public opinion research, social media scans, their own words, etc. |

| What do you want to change about that? | Consider the change in thinking that needs to happen to cause action. |

| Who do they listen to? | Identify the media they consume and the people who are likely to influence their thinking. This may be an opportunity to reach out to allies to serve as spokespeople if they might carry more weight with certain audiences. |

7. Be Explicit About the Intertwined Relationship Between Racism and Economic Opportunity and the Reverberating Consequences.

Many audiences prefer to think that socio-economic factors stand on their own and that if, say, the education system were more equitable, or job opportunities more plentiful, then we would see equal opportunity for everyone. Racism perpetuates poverty among BIPOC and leads these communities to be stratified into living in neighborhoods that lack the resources of white peers with similar incomes. That said, we need to be clear that racism causes more and different problems than poverty, low-resourced neighborhoods or challenged educational systems do and that fixing those things is not enough. They are interrelated, to be sure, but study after study, as well as so many people’s lived experiences, show that even after adjusting for socio-economic factors, racial inequity persists.

Example:

Black boys raised in America, even in the wealthiest families and living in some of the most well-to-do neighborhoods, still earn less in adulthood than white boys with similar backgrounds, according to a new study that traced the lives of millions of children.

White boys who grow up rich are likely to remain that way. Black boys raised at the top, however, are more likely to become poor than to stay wealthy in their own adult households.

Even when children grow up next to each other with parents who earn similar incomes, black boys fare worse than white boys in 99 percent of America. And the gaps only worsen in the kind of neighborhoods that promise low poverty and good schools.[6]

8. Describe How Racial Bias and Discrimination Hold Us All Back.

In addition to showing how discrimination and unequal opportunity harm people of color, it’s important to explain how systemic biases affect all of us and prevent us from achieving our full potential as a country. We can never truly become a land of opportunity while we allow racial inequity to persist. And ensuring equal opportunity for all is in our shared economic and societal interest. In fact, eight in ten Americans believe that society functions better when all groups have an equal chance in life.[7]

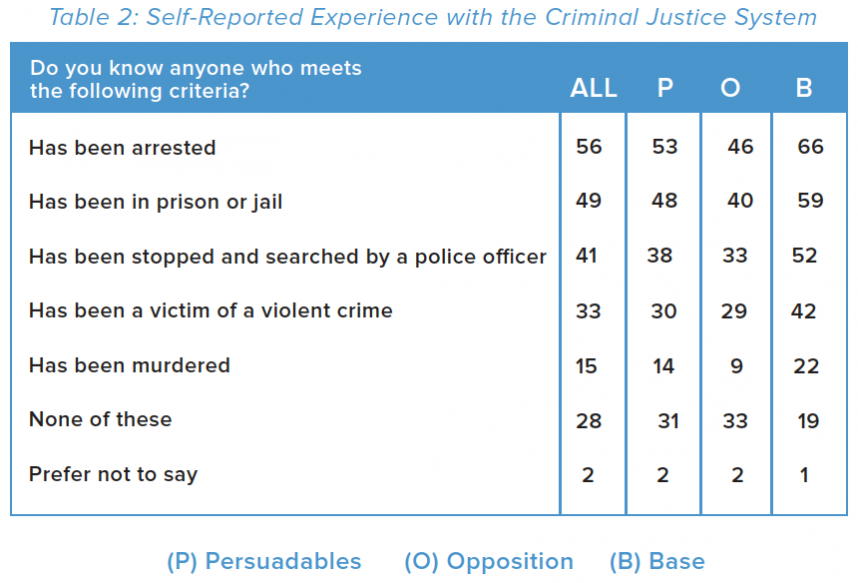

Research also shows that people are more likely to acknowledge that discrimination against other groups is a problem – and more likely to want to do something about it – if they themselves have experienced it. Most people have at some point felt on the “outside” or that they were unfairly excluded from something, and six in ten report that they’ve experienced discrimination based on race, ethnicity, economic status, gender, sexual orientation, religious beliefs or accent.[8] Reminding people of this feeling can help them think about what racism and oppression really mean for others as well as themselves.

Sample Language:

Virtually all of us have been part of a family with kids, some of us are single parents, and many of us will face disabilities as we age. Many of those circumstances lead to being treated differently – maybe in finding housing, looking for a job, getting an education. We need strong laws that knock down arbitrary and subtle barriers to equal access that any of us might face.

Examples:

“Discrimination isn’t just an insult to our most basic notions of fairness. It also costs us money, because those who are discriminated against are unable to make the best use of their talents. This not only hurts them, it hurts us all, as some of our best and brightest players are, in essence, sidelined, unable to make their full contributions to our economy.” – David Futrelle, Economic Reporter in Time Magazine[9]

“Racial inclusion and income inequality are key factors driving regional economic growth, and are positively associated with growth in employment, output, productivity, and per capita income, according to an analysis of 118 metropolitan regions. … Regions that became more equitable in the 1990s—with reductions in racial segregation, income disparities, or concentrated poverty—experienced greater economic growth as measured by increased per capita income.” – PolicyLink publication, “All-In Nation”[10]

9. Listen to and Center the Voices of BIPOC.

As social justice advocates, we should be accustomed to centering the voices of those who are most affected by any issue. It should go without saying that when talking about racism, that BIPOC should lead the strategies about how to counter it and dismantle white supremacy. This means:

- Taking cues from anti-racist BIPOC leaders on things like preferred language and strategy;

- Reducing erasure and unpaid labor by giving credit and/or compensation to BIPOC who have sparked movements, coined terms, tested and spread language and so on; and

- Being vigilant in ensuring that those who have power in our movement share that power with BIPOC, particularly those whose voices have been marginalized and those who experience multiple barriers due biases that affect them intersectionally on many levels.

Centering anti-racist BIPOC voices does not mean expecting members of each group to relive their particular oppression by describing it — or examples of it — for the benefit of the larger movement.

It also does not mean expecting only BIPOC to speak out about racism and oppression. There is room for many voices and a role for different people with different audiences to do the work of changing the narrative about race in this country.

10. Embrace and Communicate Our Racial and Ethnic Diversity while Decentering Whiteness as a Lens and Central Frame.

Underscore that different people and communities encounter differing types of stereotypes and discrimination based on diverse and intersectional identities. This may mean, for example, explaining the sovereign status of tribal nations, the unique challenges posed by treaty violations, and the specific solutions that are needed. At the same time, we need to place whiteness in the context it deserves: as a part of the larger whole and not the center of it. Too often even well-meaning language assume white as the “norm,” which implies that anyone else is an “other.”

Sample Language:

The United States purports to revere the ideals of equality and opportunity. But we’ve never lived up to these ideals, and some of us face more barriers than others in achieving this because of who we are, what we look like or where we come from. We have to recognize this and move toward the ideal that we should all be able to live up to our own potential, whether we are new to this country, or living in disadvantaged neighborhoods, on reservations that are facing economic challenges, or in abandoned factory towns.

Example:

“We affirm our commitment to stand against environmental racism and to support Indigenous sovereignty. Across the United States, Black and Brown communities are subject to higher rates of asthma and other diseases resulting from pollution and malnutrition; as demonstrated recently not only at Standing Rock but also through the water crisis in Flint, Michigan. Our neighborhoods are more likely to have landfills, toxic factories, fracking, and other forms of environmental violence inflicted on them. We will not let this continue.” – Million Hoodies, blog[11]

“At best, white people have been taught not to mention that people of colour are ‘different’ in case it offends us. They truly believe that the experiences of their life as a result of their skin colour can and should be universal. I just can’t engage with the bewilderment and the defensiveness as they try to grapple with the fact that not everyone experiences the world in the way that they do.

They’ve never had to think about what it means, in power terms, to be white, so any time they’re vaguely reminded of this fact, they interpret it as an affront. Their eyes glaze over in boredom or widen in indignation. Their mouths start twitching as they get defensive. Their throats open up as they try to interrupt, itching to talk over you but not to really listen, because they need to let you know that you’ve got it wrong.” – Reni Eddo-Lodge, author[12]

“The internment was a dark chapter of American history, in which 120,000 people, including me and my family, lost our homes, our livelihoods, and our freedoms because we happened to look like the people who bombed Pearl Harbor. … ‘National security’ must never again be permitted to justify wholesale denial of constitutional rights and protections. If it is freedom and our way of life that we fight for, our first obligation is to ensure that our own government adheres to those principles. Without that, we are no better than our enemies. … The very same arguments echo today, on the assumption that a handful of presumed radical elements within the Muslim community necessitates draconian measures against the whole, all in the name of national security.” – George Takei, actor, in the Washington Post[13]

Applying the Lessons

VPSA: Value, Problem, Solution, Action

One useful approach to tying these lessons together is to structure communications around Value, Problem, Solution, and Action, meaning that each message contains these four key components: Values (why the audience should care, and how they will connect the issue to themselves), Problem (framed as a threat to the shared values we have just invoked), Solution (stating what you’re for), and Action (a concrete ask of the audience, to ensure engagement and movement).

EXAMPLE

Value

To work for all of us, our justice system depends on equal treatment and investigations based on evidence, not stereotypes or bias.

Problem

But many communities continue to experience racial profiling, where members are singled out only because of what they look like. In one Maryland study, 17.5% of motorists speeding on a parkway were African-American, and 74.7% were white, yet over 70% of the drivers whom police stopped and searched were black, and at least one trooper searched only African American. Officers were no more likely to find contraband on black motorists than white motorists. These practices erode community trust in police and make the goal of true community safety more difficult to achieve.

Solution

We need shared data on police interactions with the public that show who police are stopping, arresting and why. These kinds of data encourage transparency and trust and help police strategize on how to improve their work. They also help communities get a clear picture of police interactions in the community.

Action

Urge your local police department to join police from around the country and participate in these important shared databases.

EXAMPLE

Value

We’re a better country when we make sure everyone has a chance to meet his, her, or their potential. We say we’re a country founded on the ideals of opportunity and equality and we have a real responsibility to live up to those values. Racism is a particular affront to our values and we need to do everything in our power to end it.

Problem

Yet we know that racism persists, and that its effects can be devastating. For instance, African American pregnant women are two to three times more likely to experience premature birth and three times more likely to give birth to a low birth weight infant. This disparity persists even after controlling for factors, such as low income, low education, and alcohol and tobacco use. To explain these persistent differences, researchers now say that it’s likely the chronic stress of racism that negatively affects the body’s hormonal levels and increases the likelihood of premature birth and low birth weights.

Solution

We all have a responsibility to examine the causes and effects of racism in our country. We have to educate ourselves and learn how to talk about them with those around us. While we’ve made some important progress in decreasing discrimination and racism, we can’t pretend we’ve moved beyond it completely.

Action

Join a racial justice campaign near you.

EXAMPLE

Value

We believe in treating everybody fairly, regardless of what they look like or where their ancestors came from.

Problem

But what we believe consciously and what we feel and do unconsciously can be two very different things and despite our best attempts to rid ourselves of prejudices and stereotypes, we all have them – it just depends how conscious they are. All of us today know people of different races and ethnicities. And we usually treat each other respectfully and joke around together at work. But for most of us – Americans of all colors – the subtle or not so subtle attitudes of our parents or grandparents, who grew up in a different time, are still with us, even if we consciously reject them.

Solution

Personally, I look forward to the day when we can all see past color—all of us, white and black, brown and Asian. To do that, we all have to be aware of what’s going on in our own heads right now. And how that collective bias has shaped our history and where we are now.

Action

But we’re just not there yet. Let’s make it a priority to get there. [14]

[1] http://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/envisioning-enacting-racial-justice-rinku-sen-force-behind-race-forward-n459996

[2] The Sentencing Project. Reducing Racial Disparity in the Criminal Justice System: A Manual for Policymakers, 2008

[5] http://agendatobuildblackfutures.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/BYP100-Agenda-to-Keep-Us-Safe-AKTUS.pdf

[7] The Opportunity Agenda/Langer Associates. The Opportunity Survey, 2014.

[8] Ibid.

[12] Reni Eddo-Lodge: Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race, The Guardian (May 31, 2017) https://www.theguardian.com/news/audio/2017/may/31/why-im-no-longer-talking-to-white-people-about-race-podcast

[13] George Takei: They interned my family. Don’t let them do it to Muslims Washington Post (November 18, 2016). https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2016/11/18/george-takei-they-interned-my-family-dont-let-them-do-it-to-muslims/?utm_term=.8e15097e3b44

[14] Modified from messages tested in Speaking to the Public about Unconscious Prejudice: Meta-issues on Race and Ethnicity. Drew Westen, Ph.D. March 2014

The Central Park Five case involved the assault and rape of a White female jogger and the wrongful arrest and conviction of four African-American and one Latinx teenagers—Kevin Richardson, Antron McCray, Yusef Salaam, Kharey Wise, and Raymond Santana. The young men spent between six and 13 years in prison before being exonerated in 2002 when another man confessed to the crime.

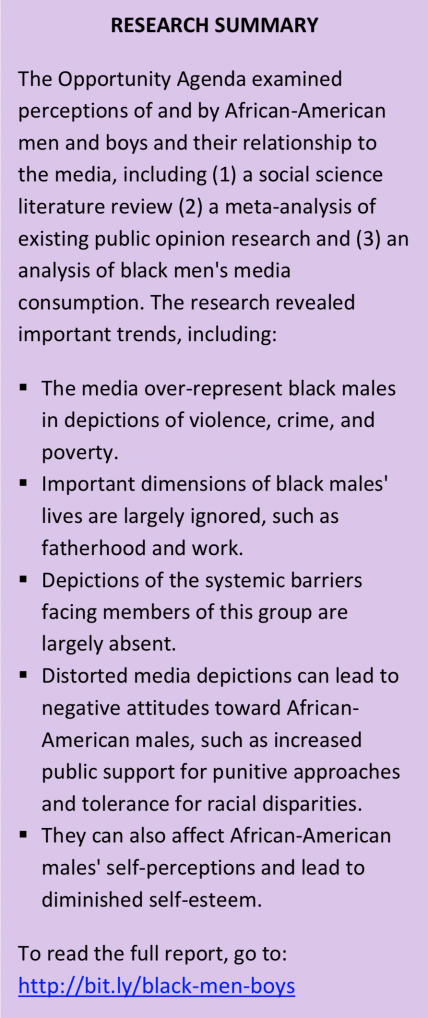

The Central Park Five case involved the assault and rape of a White female jogger and the wrongful arrest and conviction of four African-American and one Latinx teenagers—Kevin Richardson, Antron McCray, Yusef Salaam, Kharey Wise, and Raymond Santana. The young men spent between six and 13 years in prison before being exonerated in 2002 when another man confessed to the crime. Stereotypes and popular myths. Distorted media coverage and portrayals have contributed to the perception that Black men and boys should be viewed as threats and sources of violence. Our research shows that Black men and boys are more likely to be depicted as threatening, and news outlets are more likely to depict Black men and boys as committing crimes when compared to their arrest rates. These media stories contribute the myth of Black criminality contrary to what research shows.

Stereotypes and popular myths. Distorted media coverage and portrayals have contributed to the perception that Black men and boys should be viewed as threats and sources of violence. Our research shows that Black men and boys are more likely to be depicted as threatening, and news outlets are more likely to depict Black men and boys as committing crimes when compared to their arrest rates. These media stories contribute the myth of Black criminality contrary to what research shows.