Shifting the Narrative

INTRODUCTION

Both research and our lived experience consistently show that the language we use and the stories we tell play a significant role in shaping our views of the world and, ultimately, the policies we support. As the concept of “narrative” has grown in prominence within the advocacy space, more stakeholders are recognizing the centrality of storytelling to systemic change. But how do we define narrative and the elements that contribute to a successful narrative change strategy? Is change inevitable or the product of coordinated efforts that are possible to replicate?

At The Opportunity Agenda, we define narrative as: a Big Story, rooted in shared values and common themes, that influences how audiences process information and make decisions. Narratives are conveyed not only in political and policy discourse, but also in news media, in popular culture, on social media, and at dinner tables across communities.

To lay the groundwork for a sustained 21st century narrative change effort promoting mobility from poverty, criminal justice reform, and opportunity for all, The Opportunity Agenda embarked on a six-part narrative research study, with the aim of identifying the essential and replicable elements of past successful efforts, gleaning the insights captured in academic literature, consulting with diverse leaders from practice, and sharing our analysis and recommendations broadly with the field.

To this end, we chose a range of narrative-shift examples to study. Some were long-term narrative-shift efforts that resulted in shifts to both cultural thinking and policy; others were shorter-term, single-issue–focused campaigns with a particular policy goal that required a shift in narrative to achieve.

Across efforts, it is clear that narrative change does not happen on its own, particularly around contested social justice issues. It typically results from a sophisticated combination of collaboration, strategic communications tactics, and cultural engagement, all attuned to key audiences and societal trends. It requires both discipline and investment. The involvement of people whose lives are directly impacted by the narrative change being attempted is critical in the development and deployment of strategy. The process is a feedback loop because shifting narratives over time requires listening and learning from what is and is not working and incorporating that back into movement goals, more refined research, and narrative evolution.

External circumstances change, moreover, requiring recalibration and, sometimes, reformulation. A human rights narrative that worked before the events of Sept. 11, 2001, for example, would have to evolve in the years immediately after those events. Conversely, a more populist and transformative economic justice narrative became possible after the economic crisis and rising inequality of the past decade. Ignoring those seismic changes risks clinging to a narrative that has become out of date.

Among these very divergent and diverse case studies, there are consistent tactics, trends, and revelations that we found throughout. We believe that the recommendations below, as determined through our analysis, can provide social justice advocates, policymakers, activists, and media commentators with insight into the elements of successful narrative shift efforts, as well as recommendations about what to consider when undertaking such campaigns.

…narrative change does not happen on its own, particularly around contested social justice issues. It typically results from a sophisticated combination of collaboration, strategic communication tactics, and cultural engagement, all attuned to key audiences and societal trends.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Design a long-term strategy that is rooted in values. By clearly communicating what was at stake in the form of core values, many of the actors in these campaigns were able to speak to their audiences’ value systems and emotions. Doing so enabled them to organize their messaging around a constant theme over the long term and use that framework to identify the stories and statistics they needed, depending on the circumstances or messaging opportunity.

In the case of the death penalty and racial profiling, the central values were fairness and equal treatment under the law. Instead of filling their messages with only statistics that showed unequal treatment, advocates consistently tied their arguments back to the systemic racial biases that were causing the statistically bad outcomes. That basic threat to values meant that arguing for small changes to systems that inherently perpetrate unequal treatment was less acceptable to core audiences.

Know and analyze the counternarrative. While this may seem obvious—we are all too familiar with the narratives that work against our strategies—it’s important to take a moment to assess what is really resonating with audiences about the counternarrative.

For instance, in the strategy to “end welfare as we know it” advocates tapped into the stated desire to help those experiencing poverty and fashioned their opposition to anti-poverty programs as concern for their effects on recipients, particularly Black communities. They pointed to purported phenomena like the culture of dependency and the breakdown of the African American family. Doing so allowed them to shift quickly into more racially-charged props such as the welfare queen trope.

Identify and dismantle the assumptions the counternarrative relies on. Anti-death penalty advocates keyed into their opponents’ reliance on what was “working” in the criminal justice system. By focusing on that pragmatism, they were able to flip the script to point out the ways that the death penalty was actually an amplified result of so many things that weren’t working in the system, particularly when it came to racial bias. By throwing into question the assumption that the system was fair, they were able to undermine confidence in execution as a penalty and successfully argue, in many cases, for its abolition. The anti-rape movement began by taking these assumptions head-on and working to dismantle the various “rape myths” that pervaded society. By finding ways to consistently counter these dominant ideas about sexual violence, advocates were able to change the conversation, to some extent, in court rooms, pop culture and everyday conversations.

Establish your own frame and tell an affirmative story. While counternarratives and external factors beyond the direct control of advocates appear to play a significant role in shaping narratives, these studies also indicate that the advocates best positioned to respond to unpredictable external variables—or the activity of the opposition—all gained ground following the adoption of offensive communications strategies.

In the case of both the anti-death penalty and anti-gun movements, going on the offensive changed the game. Armed with an effective communications strategy, advocates can reset the terms of the debate and make considerable headway in challenging the efficacy of the death penalty and the imagined dominance of the National Rifle Association. While the anti-rape movement began very much in reaction to rampant myths and the resulting harmful policies and behavior, advocates were able to reframe the debate into a narrative of empowerment and justice. While still being against something—sexual violence and harassment—the narrative started to become more about being for equal treatment and accountability.

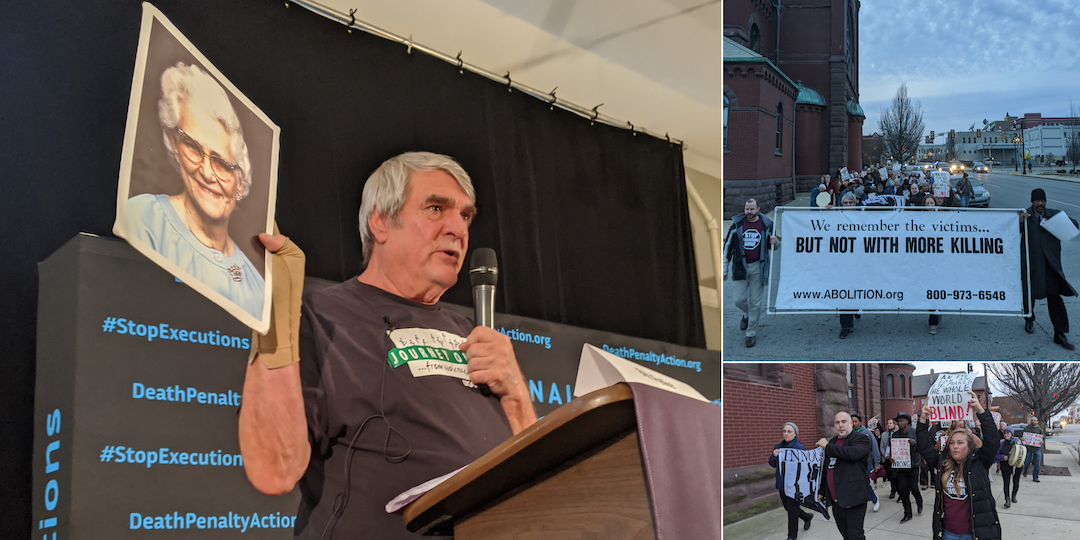

Center the voices of those who are most affected and connect them to systemic solutions. In the cases of the #MeToo, racial profiling, and anti-gun violence movements, the strategy of spotlighting survivors’ stories was a crucial part of developing the narrative. Equally important, from a strategic viewpoint, was linking those stories to systemic solutions to avoid asking audiences only for sympathy for the individuals involved. Instead, advocates were able to present systemic solutions that would require policy-level change. Also strategic is bringing in new, unexpected messengers, as anti-death penalty advocates did when forming alliances with families of murder victims who oppose the death penalty

Broaden the implications of the problem and the benefits of the solution. While it is important from both a narrative and ethical standpoint to center the voices of the people who are most affected, it is also important to compel audiences to see how these issues affect us all. Living in a society that does not tolerate racial bias in the criminal justice system, sexual violence and harassment, the gun violence epidemic to continue to cost so many lives, the inhumane treatment of animals, or people living in extreme poverty in our wealthy nation is better for us all if we want to consider ourselves a nation of conscience.

Make a clear plan, but be ready to be nimble. One of the clearest takeaways from our analysis has been the significant variation in the tools and tactics adopted between cases, in large part due to the significant role of external/unpredictable factors. For instance, in the case of the death penalty, overarching discourse shifted significantly due to crime rates and scientific developments (specifically, DNA analysis). Advocates adopted and shifted tactics as a result of these external tipping points with varying degrees of success. Animal rights activists had long protested whale captivity, as well as other use of animals in captivity for entertainment purposes. By leveraging Blackfish, they were able to take what started as a successful documentary and quickly create an entire campaign. The question remains if they could have taken it further by pushing a larger narrative about captivity that may have then become useful with the somewhat unexpected success of the 2020 series Tiger King.

Living in a society that does not tolerate racial bias in the criminal justice system, sexual violence and harassment, the gun violence epidemic to continue to cost so many lives, the inhumane treatment of animals, or people living in extreme poverty in our wealthy nation is better for us all if we want to consider ourselves a nation of conscience

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Opportunity Agenda wishes to thank and acknowledge the many people who contributed their time, energy, and expertise to the research and writing of this report.

- Bryan Stevenson, Founding Director of the Equal Justice Initiative and author of Just Mercy

- Diann Rust-Tierney, Director of the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty (NCADP)

- Richard Dieter, Founding Director of the Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC)

- Robert Dunham, Executive Director of DPIC

- Sister Helen Prejean, abolition activist and author of Dead Man Walking

- Frances Fox Piven, PhD, Distinguished Professor Emeritus at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York

- Martin Gilens, PhD, Professor of Politics at Princeton University

- Lee Cokorinos, Director of Democracy Strategies

- Rebecca Vallas, Senior Fellow, Center for American Progress

- Caty Borum Chattoo, documentary film producer, author, and Executive Director of the Center for Media & Social Impact at the American University School of Communication

- Louie Psihoyos, Academy Award-winning documentary filmmaker and Executive Director of the Oceanic Preservation Society

- Denise Beek, Chief Communications Officer, “me too”

- Moira O’Neil, PhD, Vice President of Research Interpretation, FrameWorks Institute

- Kenyora Parham, Executive Director, End Rape on Campus

- Nancy Parrish, Founder and Executive Chair, Protect Our Defenders

- Juhu Thukral, Founder + Principal, Apsara Projects LLC

- Brooke Foucault Welles, PhD, Associate Professor in the Department of Communication Studies, Northeastern University

- Fatima Goss Graves, President and CEO of the National Women’s Law Center

- Clark Neily, libertarian attorney behind the Heller lawsuit, Vice President for Criminal Justice, Cato Institute

- Robyn Thomas, Executive Director, Giffords Law Center

- Lori Haas, Senior Director of Advocacy, Coalition to Stop Gun Violence

- Josh Horwitz, Executive Director, Coalition to Stop Gun Violence

- John Crew, Founding Director of the ACLU’s Campaign Against Racial Profiling

- Ira Glasser, former Executive Director of the ACLU

- David A. Harris, author of Profiles in Injustice

- Wade Henderson, former President and CEO of The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights

- Laura W. Murphy, former Director of the ACLU Washington Legislative Office

- Reggie Shuford, Executive Director of the ACLU of Pennsylvania and former lead racial profiling litigator for the ACLU

We further acknowledge the contributions of the extraordinary team that put this report together. Research and authorship of this report was conducted by Loren Siegel, with research and editing support by former Opportunity Agenda Director of Research Lucy Odigie-Turley. Other members of the research team include Lashaya Howie, PhD. candidate in Anthropology at Chicago University; Will Coley of Aquifer Media; and Charlie Sherman of The Opportunity Agenda. Illustrations were created by Sharon Bach of 13milliseconds, and design and layout were completed by Lorissa Shepstone of Being Wicked. Margo Harris served as copy editor. The Opportunity Agenda Communications and Editorial Director Elizabeth Johnsen oversaw outreach and distribution coordination, and Director of Narrative and Engagement Julie Fisher-Rowe authored and managed the research outcome and recommendation process. Overall supervision and guidance was provided by The Opportunity Agenda President Ellen Buchman.

Finally, this report would have not been possible without the support of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

METHODOLOGY

Authors used a mix of interviews and literature reviews, which are detailed in each case study, to describe the timeline, strategy, turning points, and the like for each campaign. In addition, social media analysis was incorporated into each study using the following methodology.

SOCIAL MEDIA ANALYSIS

Existing research has pointed to the usefulness of keywords tracking, sentiment analysis, and social media volume in examining how particular topics come in and out of public interests and the news cycle. However, as noted by James P. Houghton and colleagues in their journal article exploring approaches to social media discourse analysis, these traditional methods present important limitations, specifically the inability to connect volume trends, positive or negative sentiment, and topic clusters with the embedded meaning and values that members of the public may prescribe to any given event.1 As such,

…To interpret events, individuals must make connections between an event and historical parallels or concepts in the public discourse. It is thus the expressed connections between ideas, not merely the ideas themselves, which must be tracked, categorized, and interpreted as samples “ from an underlying semantic structure” (Houghton JP, Siegel M, Madnick S, et al., 2017, p. 4).

The authors propose a new approach that makes use of “semantic networks” as a strategy for revealing the “distinct clusters of connected ideas.” They argue that as these distinct clusters grow and evolve, they have the potential to influence society’s interpretation and response to events. What this study and other proposed approaches to social media analysis highlight is the centrality of historical context, interpretation, and existing sociological methods to any examination of social media data.

Using our existing understanding of the dominant narratives and themes that have governed the narratives examined in this research, we made use of Brandwatch, a platform that aggregates social media content, to take a closer look at how online discourse has mirrored, and ultimately reshaped, wider public attitudes.

1 Houghton JP, Siegel M, Madnick S, et al. Beyond Keywords: Tracking the evolution of conversational clusters in social media. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Working Paper CISL, 2017.