In this case study, The Opportunity Agenda explores a narrative shift that transpired over a period of almost 50 years—from 1972, a time when the death penalty was widely supported by the American public, to the present, a time of growing concern about its application and a significant drop in support. It tells the story of how a small, under-resourced group of death penalty abolitionists came together and developed a communications strategy designed to raise doubts in people’s minds about the system’s fairness that would cause them to reconsider their views.

In its early days, the abolition movement was composed of civil liberties and civil rights organizations, death penalty litigators, academics, and religious groups and individuals. Later, new and influential voices joined who were directly impacted by the death penalty, including family members of murder victims and death row exonerees. Key players used a combination of tactics, including coalition building—which brought together litigators and grassroots organizers—protests and conferences, data collection, storage, and dissemination, original research followed by strategic media placements, and original public opinion research.

This case study highlights the importance of several factors necessary in bringing about narrative shift. Key findings include:

- It can be a long haul. In the case of issues like the death penalty, with its heavy symbolic and racialized associations, change happens incrementally, and patience and persistence on the part of advocates are critical.

- Research matters. Although limited to a few focus groups, the public opinion research undertaken in 1997 was critical in terms of both informing the communications strategy going forward and building unity among stakeholders.

- Going on the offensive can change the game. Armed with an effective communications strategy, advocates can reset the terms of the debate and make considerable headway.

- Bring in diverse voices. New messengers, especially “strange bedfellows”—in this case, families of murder victims who oppose the death penalty—can have a big impact.

METHODOLOGY

Our research methodology included in-depth interviews with key stakeholders, a document review, and a scan and analysis of traditional and social media.

INTERVIEWEES:

- Richard Dieter, founding director of the Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC)

- Robert Dunham, current director of DPIC

- Sister Helen Prejean, longtime abolition activist and author of Dead Man Walking

- Diann Rust-Tierney, director of the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty (NCADP)

- Bryan Stevenson, founding director of the Equal Justice Initiative and author of Just Mercy

We analyzed both public opinion data and traditional and social media content to corroborate and validate our interviewees’ observations. Leading research organizations such as Roper, Gallup, and Pew have been measuring changes in public opinion on the death penalty for many years, making it possible to see trends clearly. We also had access to proprietary qualitative research conducted by the ACLU. To identify media trends, we developed a series of search terms and used the LexisNexis database. For social media trends we utilized the Crimson Hexagon online data library. Our interviews with key stakeholders and our review of public opinion and media/social media trends reveal a dynamic relationship that continues to reshape the public narrative about the death penalty in America.

Based on a series of historical benchmarks, we identified five time periods and their external (i.e., events beyond the control of the advocates) and field-wide tipping points that comprised the stages of narrative shift:

EARLY YEARS: 1972–1980

EXTERNAL TIPPING POINTS

- A 4-year moratorium begins following the 1972 Supreme Court decision in Furman v. Georgia. The death penalty statutes in 40 states are voided as arbitrary, cruel, and unusual in violation of the Eighth Amendment.

- Surveys show public support for the death penalty for those convicted of murder is less than 50 percent.

- States undertake reforms and the Supreme Court reinstates the death penalty in 1976 in Gregg v. Georgia.

- The execution by firing squad of Gary Gilmore, the first person to be executed post-Gregg, has intense media coverage

- An uptick in crime reported and sensationalized by media occurs.

FIELD-WIDE TIPPING POINTS

- The National Coalition Against the Death Penalty is established.

- Strategies other than litigation are explored and implemented.

THE 1980s

EXTERNAL TIPPING POINTS

- Fear of crime increases. “If it bleeds, it leads” media coverage (i.e., fear-based media coverage focusing on murder and mayhem because it increases sales) intensifies it.

- Law and order and racist dog-whistle political rhetoric increases, and Ronald Reagan is elected.

- As new death sentences increase, appeals and procedural delays come under attack.

- Support for the death penalty climbs; politicians take note.

- The Supreme Court rejects racial bias argument in McClesky v. Kemp.

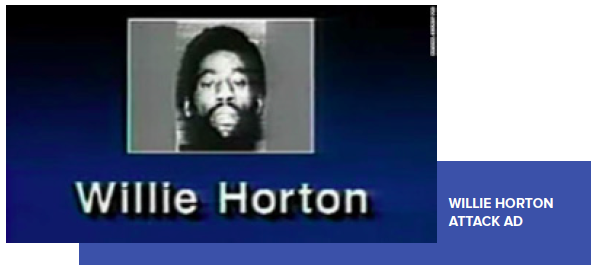

- Bush/Dukakis campaign, the “Willie Horton ad,” and Dukakis’s anti-death penalty stance are shown to be a political liability.

FIELD-WIDE TIPPING POINTS

- None: Abolition movement on the defensive.

THE 1990s

EXTERNAL TIPPING POINTS

- Candidate Clinton presides over the Arkansas execution of a mentally disabled man.

- In reaction to the Oklahoma City bombing, the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act was enacted.

- New death sentences and executions reach an all-time high.

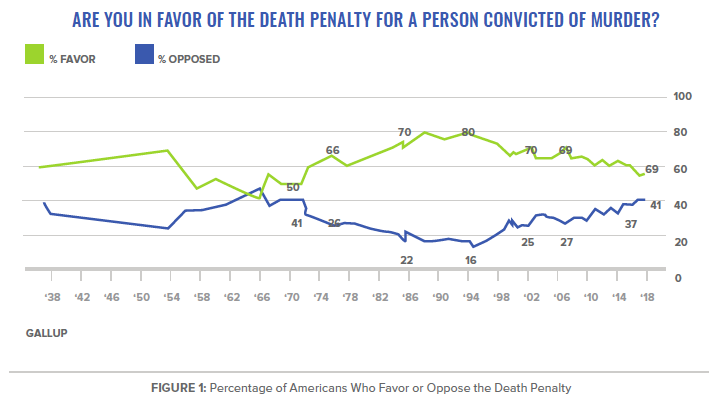

- Eighty percent of the public favors the death penalty for persons convicted of murder.

FIELD-WIDE TIPPING POINTS

- The Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC) is established.

- The Innocence Project and the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) are founded.

- 60 Minutes airs a feature story about EJI’s efforts to free Walter McMillian from Alabama’s death row.

- Dead Man Walking and The Green Mile films are released.

- Kirk Bloodsworth becomes the first death row inmate to be exonerated through DNA testing.

- The American Bar Association passes a resolution calling for a moratorium on executions.

- The Northwestern School of Law holds a conference with 29 “death row refugees.”

- ACLU commissions focus groups; researchers recommend focusing on systemic unfairness.

- A 3-day gathering at the Musgrove Conference Center of leaders from around the country is held to hammer out a new communications strategy to move hearts and minds.

THE 2000s

EXTERNAL TIPPING POINTS

- Illinois Governor George Ryan declares first moratorium on executions.

- Executions and new death sentences begin to decline.

- The U.S. Supreme Court ends execution of people who have mental disabilities and people who committed crime as juveniles.

- Exonerations receive increasing media attention; Congress passes the Innocence Protection Act.

- The public supports life sentence without parole over death penalty.

- Botched lethal injection controversy grows.

- Pope Francis says the death penalty is “an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person.”

- Public support drops to a four-decade low.

- Gov. Newsom orders moratorium on executions in California, the state with the largest death row.

FIELD-WIDE TIPPING POINTS

- The National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty grows to more than 100 affiliates and adopts a state-by-state strategy.

- The DPIC website becomes a one-stop shop for journalists covering the issue; media coverage focuses on systemic flaws.

- Murder Victims Families for Human Rights is founded.

2007-2020

EXTERNAL TIPPING POINTS

- New Jersey is the first state to abolish capital punishment legislatively; nine more states follow suit.

- Governors in four states—California, Colorado, Oregon, and Pennsylvania—declare moratoriums on executions.

- Editorial support for abolition grows.

- Public support for death penalty falls to lowest point since the 1970s.

FIELD-WIDE TIPPING POINTS

- Conservatives Concerned About the Death Penalty is founded.

- Just Mercy by Bryan Stevenson is published and sells more than 1 million copies; a major film based on the book is released.

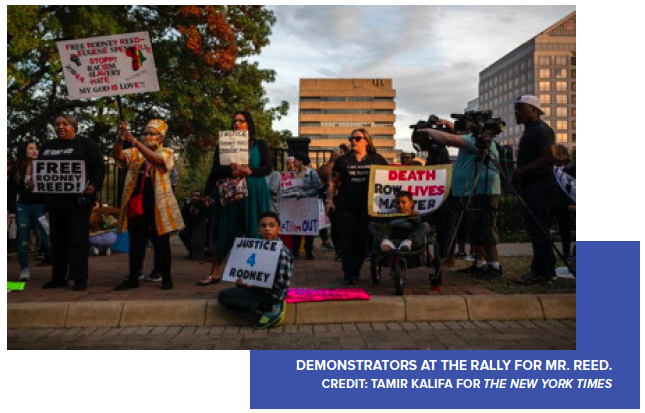

- The campaign to save Rodney Reed, a Texas death row inmate convicted by an all-white jury, wins indefinite stay of execution.

BACKGROUND

On March 23, 2020 Colorado became the twenty-second state to abolish the death penalty and the tenth to do so since 2007. Once assumed to be a permanent fixture in the nation’s criminal justice system, with a few notable exceptions the death penalty has been in retreat since the early ’00s as one state after another has either repealed their death penalty statute or imposed a moratorium on executions. As of 2020, for the first time in U.S. history the death penalty is in perfect equipoise: 25 states retain it, and 25 states reject it, either through repeal (22) or moratorium (3). Once considered a third rail in politics, opposition to the death penalty has become sufficiently mainstream for elected leaders to openly embrace it.

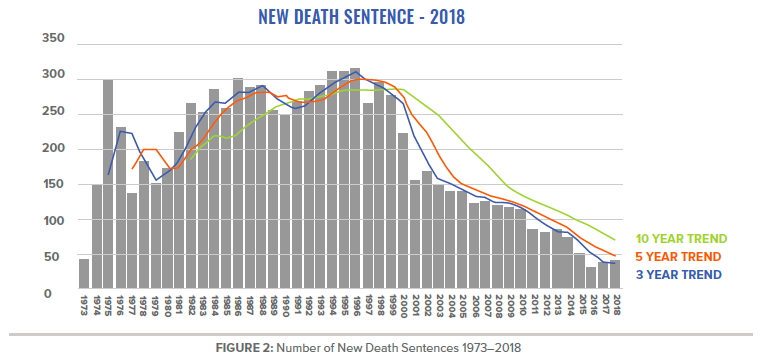

These recent policy reforms would not have been possible were it not for the erosion of public support for the death penalty. In the peak year of 1995, 80 percent of Americans supported the death penalty and only 16 percent opposed it for people convicted of murder. Today support for the death penalty is the lowest it has been in the past 40 years, with 56 percent in favor and 42 percent opposed. The decline in public support, in turn, is reflected in the imposition of fewer death sentences by juries. In 2018, 42 new death sentences were imposed as compared to 315 in 1996.

These recent policy reforms would not have been possible were it not for the erosion of public support for the death penalty. In the peak year of 1995, 80 percent of Americans supported the death penalty and only 16 percent opposed it for people convicted of murder. Today support for the death penalty is the lowest it has been in the past 40 years, with 56 percent in favor and 42 percent opposed. The decline in public support, in turn, is reflected in the imposition of fewer death sentences by juries. In 2018, 42 new death sentences were imposed as compared to 315 in 1996.

This case study describes the role that public narrative, as expressed through media coverage, popular culture, and the opinions of influential voices, has played in causing Americans to reconsider their position on what had, for decades, been a hot button issue. We look at how a relatively small movement of death penalty litigators and abolitionist advocates and activists representing arguably the most stigmatized constituency in America—people on death row—used the tools at their disposal to change the story.

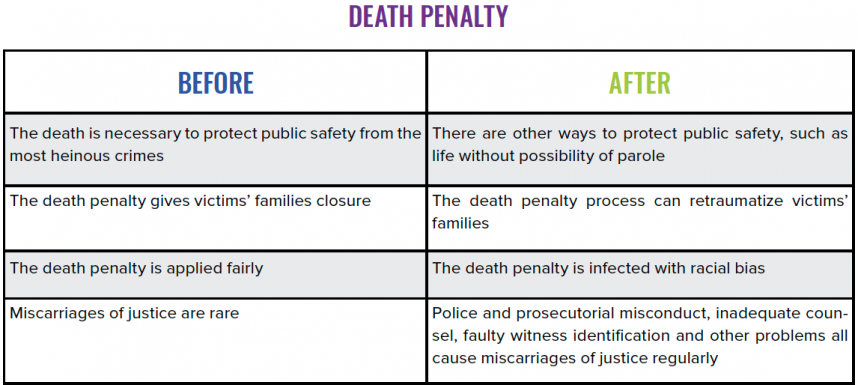

THE DEATH PENALTY NARRATIVE, THEN AND NOW

THEN

We need the death penalty to punish those who break society’s rules and bring order to a criminal justice system that does not protect the public’s safety. The finality of the death penalty brings order to chaos and brings closure for the victims’ families.

NOW

The death penalty as it’s applied in this country is flawed, is infected with racial bias, and can’t be fixed. There are other ways to protect the public’s safety that are less costly, are just as effective, and don’t run the risk of executing innocent people.

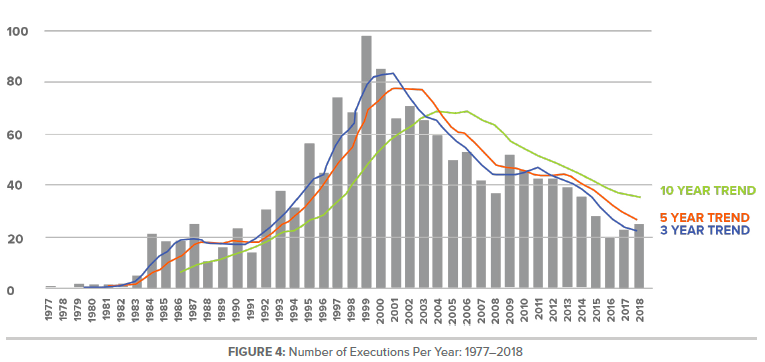

Executions were rare in this country prior to the mid-1980s. In 1965 there were seven executions nationwide, four of them in Kansas. In 1966 there was one, and in 1967 there were two. Because of how rarely it was carried out, the death penalty was relatively uncontroversial. That changed in 1972, when the U.S. Supreme Court rendered its decision in Furman v. Georgia, holding that the death penalty statute in question violated the Eighth Amendment prohibition against cruel and unusual punishments because it was applied “arbitrarily and capriciously.” The 5-4 decision had the effect of abrogating every death penalty statute in the country. All pending death sentences were reduced to life imprisonment, and states understood that they had to go back to the drawing board if they wanted their statute to pass constitutional muster.[1]

The Furman decision was the result of a litigation strategy. Diann Rust-Tierney explains:

The same tools that were available to address civil rights violations were applied here by the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund. When you have a primarily legal argument it makes you think about issues a certain way, and it makes you think about your audience a certain way. The way that the LDF and others prosecuted these cases was to amass a great deal of information and facts and data and arguments and put them before the Court, and the Court makes a ruling. At the time there was the expectation that once a case was won the issue was settled. But states went right back to the drawing board. We learned that litigation strategies have to be accompanied by the work of changing public opinion.

In the aftermath of Furman, 37 states enacted new death penalty laws, and in 1976, in the case of Gregg v. Georgia, the Supreme Court ended the de facto moratorium when it reviewed five new statutes (Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Florida, and North Carolina) and found them to be constitutional. The number of new death sentences climbed rapidly, from just under 50 in 1973 to 300 in 1975, and that number would remain relatively constant until 2001.The number of executions grew slowly at first and then rose rapidly beginning in the mid-1990s. Ninety-eight executions were carried out in the peak year of 1998. The fact that 81 percent of those executions were carried out by southern states was not insignificant. Bryan Stevenson argues that “the death penalty is lynching’s stepchild”:

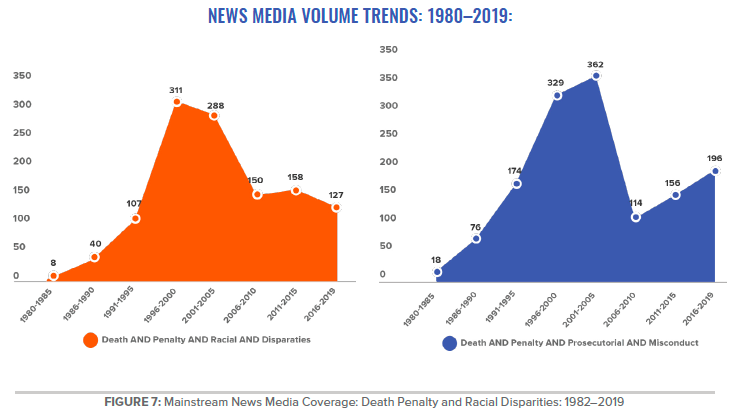

The race of the victim is the greatest predictor of who gets the death penalty in America. We moved lynchings from outside to inside in the 1940s and ’50s when the political pressure on these communities that tolerated this spectacle of violence got so great that they no longer felt they could do it with impunity. I think that connection is directly linked to what we tolerated during the era of lynching. And we use this lethal threat of violence from an electric chair to replace the threat that was created through hanging. I don’t think it’s an accident that the states with the highest lynching rates are the states with the highest execution rates. Nor do I think it’s an accident that communities in those states feel deeply burdened by our continuing willingness to kill people in this racialized way.[2]

The reinstatement of the death penalty arrived as law and order rhetoric came to dominate the public discourse. The Reagan Administration loudly attacked constitutional “technicalities” like the Exclusionary Rule and the Miranda warnings, claiming they “tied the hands of the police.” The war on drugs was declared, and politicians, concerned with being labeled “soft on crime,” enacted a raft of harsh anti-crime laws at the state and federal levels. “If it bleeds, it leads” came to dominate local media coverage, and fear of crime intensified. Underlying the growing support for the death penalty was the extent to which crime in America was racialized (i.e., experienced by whites, and others, in racial terms). According to public opinion surveys, white Americans overestimated (and still overestimate) the proportion of crime committed by people of color and the proportion of people of color who committed crime. And social science research shows that attributing crime to people of color limits empathy toward the accused and encourages retribution as the primary response to crime.[3] The death penalty, of course, is the ultimate form of retribution. The narrative promoted by “tough on crime” pundits that judges were too lenient and prisons were like country clubs also gained ground. In this environment, the death penalty was viewed as all that stood between the public and the most heinous crimes.

Prior to the Supreme Court’s 1976 decision reinstating the death penalty, there was minimal organizing and advocacy against it and abolitionists relied almost exclusively on litigation to press their case. A small group of legal organizations, most notably the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund and the ACLU, and a handful of attorneys and academics worked together to coordinate court challenges to various aspects of the death penalty. Days after the Gregg decision, Henry Schwarzschild, the head of the ACLU’s Capital Punishment Project, sent out a tersely worded mailgram to leaders of the small abolition movement:

In light of the Supreme Court decision on death sentences, we are convening a working meeting on non-litigation strategy to prevent executions and abolish capital punishment. Your attendance is urgently invites. Please advise.

The meeting, held just a few days later, led to the founding of the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty (NCADP) and the earliest efforts to mobilize a grassroots movement.[4] As the organization’s name makes clear, the goal was, and still is, the complete eradication of the death penalty in the United States. Within its first year, 40 state affiliates had joined the coalition, representing faith, civil rights, and civil liberties organizations. Eventually growing to more than 100 affiliated organizations, the NCADP spread its message of abolition, grounded in opposition to all “state-sponsored killing,” through public speaking engagements, publications including Execution Alerts that reported impending executions, and vigils.

The 1980s: “Endless Appeals and Procedural Delays”

During the decade of the 1980s the death penalty became a potent symbol of toughness on crime, and its favorability rating among the public climbed steadily. Between 1980 and 1985, media coverage of the death penalty more than tripled. By the end of 1985, the death row population exceeded 1,500 people but executions were still relatively rare, and procedural delays in carrying out executions became a contentious issue. Headlines about legally thwarted executions such as the following were common:

- Gray Execution Blocked Again (The Washington Post, July 7, 1983)

- Convicted Murderer Gets a Stay in Louisiana (Christian Science Monitor, February 12, 1981)

- Execution of Child-Killer Stayed by U.S. Court (The New York Times, March 1, 1982)

- Killer Wins Reprieve (Miami Herald, October 22, 1982)

- State High Court Overturns 2 More Death Sentences (Los Angeles Times, October 24, 1986)

The Washington Legal Foundation, Criminal Justice Legal Foundation, and other pro-death penalty organizations aggressively lobbied for limiting the appeals process and shortening the length of time between sentencing and execution. In 1989, a special committee of federal judges, set up at the request of Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist to study the judicial system’s handling of death penalty cases, recommended strict new limits on the multiple appeals filed by death row inmates. Pressure built for Congress to enact legislation curtailing the rights of people on death row.

As the 1980s came to an end, death penalty opponents were in an acutely defensive position. In 1987 the movement suffered a major legal defeat when the Supreme Court issued its ruling in McCleskey v. Kemp, rejecting the argument based on powerful statistical evidence that the application of the death penalty was racially biased.5 In 1988, the presidential race between George H. W. Bush and Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis reinforced the message that the death penalty was needed to protect public safety and that opposition to it was a definite political liability. First, the Bush campaign aired the “Willie Horton” TV attack ad.

Considered one of the most racially divisive ads in modern political history, it depicted an African American man who had been convicted of murder, who raped a white woman and stabbed her partner while furloughed from prison under a Massachusetts program in place when Dukakis, the Democratic nominee, was governor. In a voiceover, the narrator says: “Dukakis not only opposes the death penalty, he allowed first-degree murderers to have weekend passes from prison.” Between 1988 when the ad first launched and 1990, more than 1,600 articles were published in mainstream media outlets making reference to Willie Horton.

Then, during a televised debate between the candidates, Gov. Dukakis was asked whether he would support the death penalty if his wife were raped and murdered. He responded, “No, I don’t… I think you know that I’ve opposed the death penalty during all of my life. I don’t see any evidence that it’s a deterrent and I think there are better and more effective ways to deal with violent crime.” Labeled “Dukakis’ Deadly Response” by Time magazine, pundits attributed his election defeat to his answer to this question.

In spite of the opposition’s efforts to sway the public through protest, argument, and litigation, by the end of the decade the dominant narrative about the death penalty was deeply embedded in the public discourse: The death sentence was needed as a deterrent to crime and an expression of the American public’s desire to punish wrongdoers, and the delays in executions brought about by defense lawyers and liberal judges violated the public’s trust. Politicians opposed it at their peril. Abolition leaders knew that a course correction was imperative.

In the 1980s, most of us were trying to just survive the tough on crime rhetoric and we were on the defensive. In the 1990s, some of us started to talk about what we needed to do to be proactive, and that’s what gave rise to the effort around creating concerns about the death penalty as applied, rather than in the abstract.

The 1990s: The Beginning of a Contest Over Narrative

In early 1990, a small group of leading abolitionists met in New York City to come up with a plan to break through what they viewed as a stalemate. They feared that the debate had been reduced to confrontations outside prisons on the eve of executions, with one side praying and the other side calling for death. Convened by journalist and philanthropist John “Rick” MacArthur, those present expressed their frustration with the limits of what they believed had been a mostly “philosophical” argument about the morality of capital punishment. They agreed with what Justice Thurgood Marshall had written in his opinion in Furman v. Georgia: If Americans knew all the facts, they would be against the death penalty. How, then, to bring all the facts to the attention of the public?

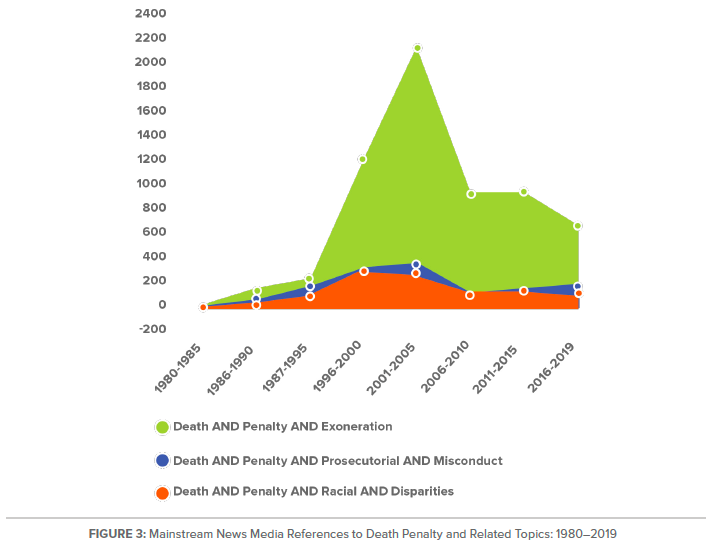

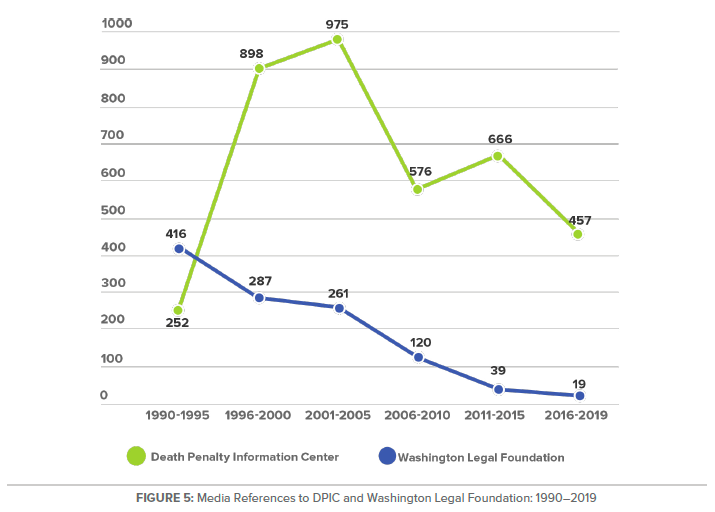

The result of that meeting was the birth of the Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC), whose mission was to “serve the media and the public with analysis and information on issues concerning capital punishment.” DPIC, with a full-time staff of one, was initially housed in the offices of Fenton Communications, a public relations agency founded by David Fenton to further the goals of the movements for the environment, public health, and human rights. DPIC engaged in intensive media relations, identifying and working with journalists to tell a different story about the death penalty. It began to publish special reports focusing on the systemic flaws in its implementation, including racial bias, prosecutorial misconduct, inadequate defense, and so on.

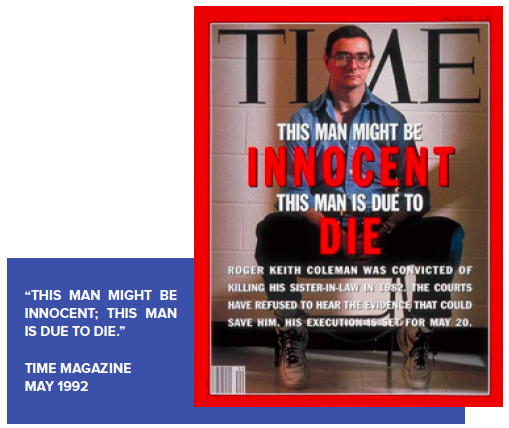

At first there was some resentment within the abolition movement about the funding of DPIC. At a time when the death penalty defense bar had so few resources, some felt the money would be better spent on providing more and better legal services to the condemned. But several early breakthroughs that demonstrated the power and potential of favorable media coverage began to win those detractors over, including:

- In May 1992 Time magazine published a cover story about Roger Keith Coleman, on Virginia’s death row for the murder of his sister-in-law. The cover headline, superimposed over a photograph of Coleman, read “THIS MAN MIGHT BE INNOCENT; THIS MAN IS DUE TO DIE.”

- In the fall of 1992 CBS’ 60 Minutes aired a feature story about Bryan Stevenson’s efforts to free Walter McMillian from Alabama’s death row, illuminating the role of racism in the railroading of an innocent black man in the Deep South.

- In June 1993, the exoneration of Kirk Bloodsworth, the first person on death row to be released as a result of DNA evidence, was covered in close to 200 stories in major U.S. newspapers and featured on television news programs nationwide.

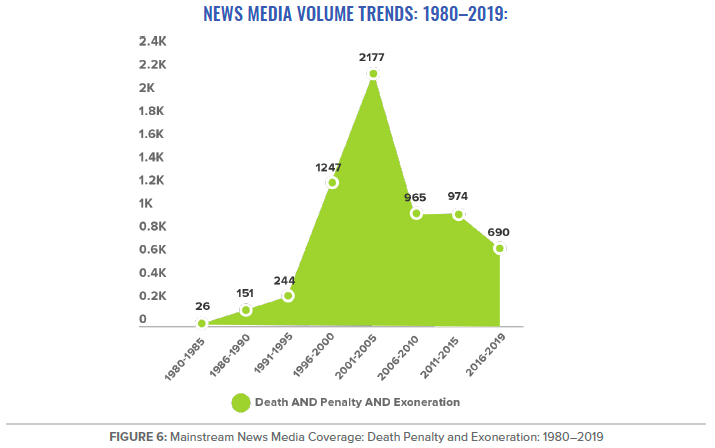

These “earned media” stories were the results of hard work by advocates armed with a proactive communications strategy. They, and others like them during the early 1990s, were at the forefront of what would become a steady stream of stories that complicated, and gradually undermined, the widespread belief that the death penalty was fair and that miscarriages of justices were rare. In 1992 two professors at Cardozo Law School, Peter Neufeld and Barry Scheck, founded the Innocence Project, putting the spotlight on the risk of miscarriages of justice by using DNA evidence to reopen cases, and the number of death row exonerations began to grow.[6] The Innocence Project, which eventually expanded into a large network of projects throughout the country, has been hugely influential in the narrative shift process. Since its founding, it has been featured in close to 7,000 news media articles. In April 2020 Netflix released a nine-part documentary series, The Innocence Files, which features the work of the Innocence Project.

Other events during this decade also contributed to growing unease about the death penalty. Two award-winning films based on best-selling books were released. In 1996, Dead Man Walking, based on a book by Sister Helen Prejean of the same title, came out to wide critical acclaim. The film introduced a mass audience not only to Sister Prejean, played by Susan Sarandon, and her moral crusade against the death penalty, but also to the character of Earl Delacroix, the father of one of the victims, who opposed the execution of his son’s murderer. The film’s portrayal of a grieving father who disputed the claim that the execution would help him find “closure” presented viewers with a counternarrative to the one they had been given. In 1999, The Green Mile, a fantasy crime drama starring Tom Hanks and based on a book by Stephen King, told the story of the execution of an innocent black man and the emotional toll it took on the prison official supervising the execution. Speaking of the impact murder victims’ families and corrections officials would have in voicing this counternarrative, Sister Helen Prejean explains:

When the New Jersey legislature was having hearings about the death penalty, sixty-two murder victims’ families testified saying ‘don’t kill for us.’ More and more victims’ families are saying the death penalty re-victimizes us. It puts your grief in the public spotlight. Every time there’s a change in the status of the case the media is at your door. You can’t grieve. You’re in trauma. It doesn’t help. Then there are the voices of wardens who have to carry out executions, and guards that are part of the execution squad. One warden in Florida has said publicly that he will be in therapy for the rest of his life: ‘I participated in the killing of someone who had been rendered defenseless.’

Events in Illinois were unfolding that would have an impact on public opinion nationwide. A spate of death row exonerations, some of them brought about through the investigatory efforts of journalism students at Northwestern University, put a spotlight on police and prosecutorial corruption and misconduct. By 1998, the Illinois death penalty score stood at 11 executed (since the reinstatement of the penalty in 1977) and nine exonerated. In November, the Northwestern School of Law held a conference that brought together on one stage 29 “death row refugees,” eight from Illinois and the rest from other states. An AP photo of the exonerees along with Professor Anthony Amsterdam, a well-known abolitionist attorney, was a jolting image of how serious the risk of executing the innocent really was.

Two months after the conference, the Chicago Tribune published a five-part series by two investigative reporters entitled, “Trial & Error. How Prosecutors Sacrifice Justice to Win.” A month after this hard-hitting series was published, in early 1999, another Illinois death row prisoner, Anthony Porter, was exonerated within 48 hours of his scheduled execution when an investigator hired by the Northwestern project obtained a video-recorded confession from the man who actually committed the murder. The Porter exoneration was swiftly followed by three more–Steven Smith, Ronald Jones, and Steven Manning—setting the stage for the new governor, George Ryan, to declare the country’s first moratorium on executions in January 2000. It was clear that the risk of executing the innocent was a key component of a new narrative about the death penalty. As Richard Dieter put it:

We had to reach a critical mass in the amount of information people heard about innocence. They had to hear it again and again. Innocence opened the door and you started to hear political leaders saying the reason they were stopping executions or voting to abolish the death penalty was the risk of an innocent person being put to death. Innocence was the breakthrough that was needed to deflate the pro-death penalty argument.

The progress in shifting the narrative did not lead to policy change right away. In fact, the abolition cause suffered a setback after the Oklahoma City bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in April 1995. President Bill Clinton, who had demonstrated his death penalty bona fides in 1992 when he interrupted his campaign for president to preside over the Arkansas execution of Ricky Ray Rector, a mentally disabled man, signed the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 into law. The bipartisan act greatly limited the ability of federal courts to grant writs of habeas corpus, often the only legal relief available to those on death row.[7] The number of executions was climbing steadily at this juncture, and abolition advocates felt a new sense of urgency.

In 1997, the ACLU commissioned a series of focus groups to inform the organization and its allies about the general public’s attitudes toward the death penalty. Participants were either somewhat supportive of the death penalty or had no opinion on the issue. At the time the focus groups were held, public opinion surveys showed that three-quarters of Americans supported the death penalty. In a report titled, “Making the Case for Abolishing the Death Penalty,” the research firm of Belden Russonello & Stewart advised that “overall, the groups uncovered deeply-held support for the death penalty among these participants, but the discussions also identified some possible ways to begin to erode this support through long-term education.” The report and its recommendations were shared and discussed widely with the abolition community.

The views expressed by the focus group participants demonstrated that calling for abolition had little chance of success in the near term. According to the researchers’ analysis, the overarching theme that emerged from the focus groups was “don’t get rid of the death penalty, but use it wisely.” Participants believed that the death penalty was at times administered unfairly, but they did not see the problems as serious enough to warrant ending its use. In response to a story about an innocent person who had been sentenced to death, for example, a focus group participant said:

I just don’t think that’s a good reason to not kill the people that are guilty for fear that you might make a mistake and kill someone who’s innocent. You have to hope that the judicial system is fair and is structured so that it catches those mistakes.

The direction for changing the dominant narrative became clear: The anti-death penalty movement had to expose the many ways that the judicial system was riddled with errors and unfairness and use all the tools at its disposal to communicate those problems to the American public. In other words, follow Justice Thurgood Marshall’s admonition to “shock the conscience” of the “average American.”

In 1998 the ACLU received a grant to underwrite a convening of movement leaders to build unity around a new narrative—one based on exposing and challenging systemic flaws in the administration of the death penalty, state by state. For some organizations and individuals, this approach was problematic and smacked of “greasing the rope”—fixing the death penalty system so that it worked better. Bringing everyone on board would require the time and space for in-depth discussion and debate. The convening took place over several days at the Musgrove Retreat and Conference Center on St. Simons Island, Georgia. It included a presentation by the public opinion research firm that had conducted the ACLU’s focus groups. By the end of the convening, agreement had been reached on a new narrative and the state-based strategy. According to Richard Dieter, who participated in the Musgrove convening:

The narrative shifted from a theoretical, philosophical debate to a more pragmatic approach. And that brought in a broader group of people who questioned the death penalty but didn’t necessarily oppose it on principle. The broader approach, the ‘bigger tent,’ has been effective on this issue.

From 2000–2006: A New Narrative Takes Hold

By the turn of the new millennium, support for the death penalty in cases of murder had begun its downward trajectory.[8] On January 27, 1999, Pope John Paul II condemned it as “both cruel and unnecessary” during his Papal Mass in St. Louis, reinforcing the moral imperative for a moratorium. The abolition movement had reached a critical mass in terms of influencing the debate through public appearances, media outreach, and other forms of communication. As Robert Dunham points out, the movement had also grown increasingly diverse:

There are many organizations that have made a tremendous impact. The Southern Center for Human Rights, the Equal Justice Initiative, Witness to Innocence, and the Catholic Mobilizing Network. Celebrities like Oprah Winfrey, Sister Helen Prejean and Susan Sarandon, because of her role in Dead Man Walking, attracted media attention. The National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty, the American Bar Association, Amnesty International, the Innocence Project, and the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund. Some of the most important people are the institutional capital defenders, because without them you would not see the stories of all the miscarriages of justice. They all play a vital role.

With the arrival of the internet, the Death Penalty Information Center became an even more efficient “one stop shop” for news and analysis. Between 1990 and December 31, 2019, 3,869 news articles were published in the mainstream U.S. news media referencing DPIC. In terms of overall share of media coverage, DPIC significantly outpaced its major opposition, the Washington Legal Foundation, a pro-death penalty organization.

New voices entered the debate, most significantly family members of murder victims who opposed the death penalty, and Murder Victims’ Families for Human Rights was founded. Affiliates of the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty ramped up their efforts to expose the flaws in their states’ systems, issuing public reports and engaging in legislative advocacy and local media outreach. According to Diann Rust-Tierney:

New voices entered the debate, most significantly family members of murder victims who opposed the death penalty, and Murder Victims’ Families for Human Rights was founded. Affiliates of the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty ramped up their efforts to expose the flaws in their states’ systems, issuing public reports and engaging in legislative advocacy and local media outreach. According to Diann Rust-Tierney:

The focus on changing the law at the state level—that was huge. Before, all of us thought our job was to just keep talking to people and if we convinced them to oppose the death penalty, something would happen. It was when we linked the communications strategy to actual state policy reforms that we began to see a light at the end of the tunnel.

A survey of coverage in major U.S. newspapers during this period reveals the shifting narrative in real time. More and more, journalists focused on issues that the abolition movement was pressing: the role of race and poverty; the problems of prosecutorial misconduct and inadequate counsel that led to miscarriages of justice and exonerations; the cruelty of “botched” executions. These stories reinforced the public’s growing unease and also revealed the systemic fault lines that the movement had been trying to expose. In particular, the availability of post-conviction DNA testing revealed how high the risk of executing an innocent person really was.

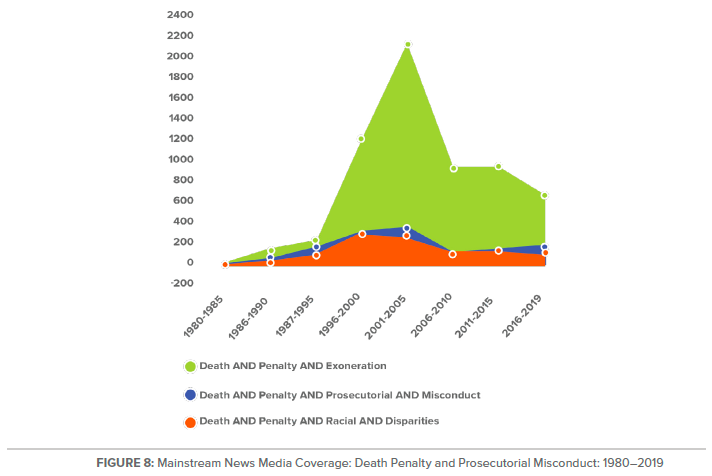

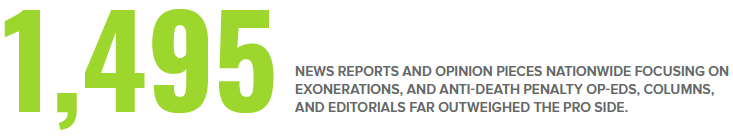

News coverage of death row exonerations began to increase in 2001 and spiked in 2003. That year there were more than 500 stories published in major U.S. newspapers highlighting the rising number of exonerations. Hundreds of stories reported on Gov. George Ryan’s moratorium on executions and his decision to grant blanket commutations during his last days in office for all 156 people still on Illinois’s death row. His statement that “Our capital system is haunted by the demon of error: error in determining guilt and error in determining who among the guilty deserves to die” received wide coverage in the print and broadcast media. Other stories reported on individual cases of exoneration around the country, some occasioned by new DNA evidence and others by evidence of prosecutorial misconduct or racial bias among jurors. Between 2003 and 2006, there were 1,495 news reports and opinion pieces nationwide focusing on exonerations, and anti-death penalty op-eds, columns, and editorials far outweighed the pro side. Other flaws in the system, including prosecutorial misconduct, incompetent defense, and racial disparities also received increasing media attention during this period.

From 2007–2020: An Era Drawing to a Close

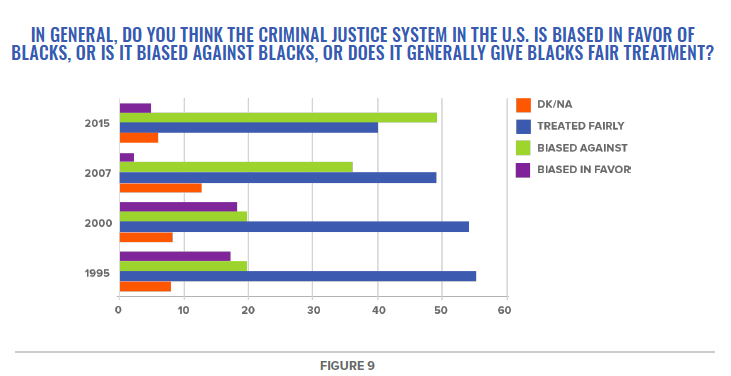

This period saw a marked increase in the number of police shootings of unarmed black men and an uptick in media coverage of these incidents. The frequency and number of police killings gave birth to the Black Lives Matter movement and a marked shift in the public’s consciousness about racial bias in the criminal justice system overall. In 1995, a majority of Americans believed the criminal justice system gave black people “fair treatment.” By 2007, the percentage that thought the system was “biased against Blacks” was on the rise, and between 1995 and 2015 it increased by almost 30 points.[9] This growing acceptance of the reality of systemic racial bias added to people’s disquiet over the death penalty.

By 2007, the efforts to shift the death penalty narrative began to bear fruit in the policymaking context. In December of that year, New Jersey became the first state to abolish capital punishment legislatively. (New York’s statute had been declared unconstitutional by the state’s high court in 2004.) New Jersey was followed by New Mexico (2009), Illinois (2011), Connecticut (2012), Maryland (2013), Nebraska (2015), Delaware (2016), Washington (2018), New Hampshire (2019), and Colorado (2020). In 2019 moratoriums were declared by the governors of four states: Pennsylvania, California, Oregon, and Colorado. The statements made by the governors explaining their reasons for suspending executions reflected the new narrative:

Our death penalty system has been, by all measures, a failure. It has discriminated against defendants who are mentally ill, black and brown, or can’t afford expensive legal representation. It has provided no public safety benefit or value as a deterrent. It has wasted billions of taxpayer dollars. But most of all, the death penalty is absolute. It’s irreversible and irreparable in the event of human error.

This moratorium is in no way an expression of sympathy for the guilty on death row, all of whom have been convicted of committing heinous crimes. This decision is based on a flawed system that has been proven to be an endless cycle of court proceedings as well as ineffective, unjust, and expensive. Since the reinstatement of the death penalty, 150 people have been exonerated from death row nationwide, including six men in Pennsylvania.

If the State of Colorado is going to undertake the responsibility of executing a human being, the system must operate flawlessly. Colorado’s system for capital punishment is not flawless.

The death penalty as practiced in Oregon is neither fair nor just; and it is not swift or certain. It is not applied equally to all.

Important new voices joined the chorus. Former prison wardens who had overseen executions, including Ron McAndrew of the Florida State Prison at Starke, Ohio Corrections Director Reggie Wilkinson, and San Quentin Warden Jeannie Woodford, publicly express their opposition. Newspapers in death penalty states published powerful editorials. In 2008, the Dallas Morning News called upon Texas, with its hyperactive death chamber, to stop the executions: “It’s the view of this newspaper that the justice system will never be foolproof and, therefore, use of the death penalty is never justified.” That same year, the Richmond Times-Dispatch, which had long supported the death penalty, changed its position stating, “The government ought to limit itself to protecting the public—and ought to refrain from playing God.” In 2013, a group of conservative thinkers and publishers formed Conservatives Concerned About the Death Penalty under the banner, “We are questioning a system marked by inefficiency, inequity, and inaccuracy.”

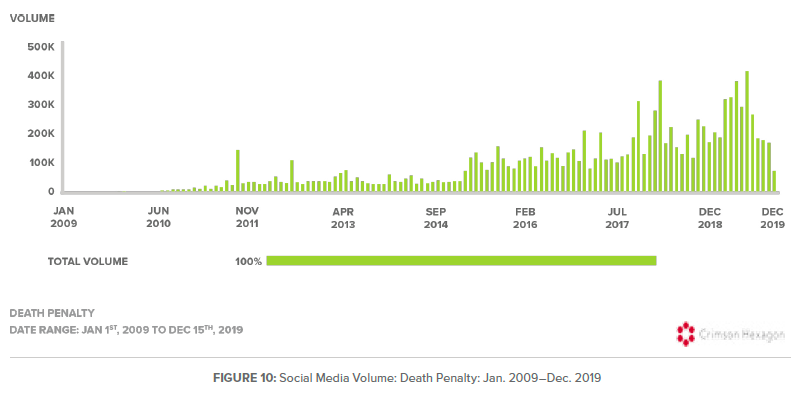

Social media came to play a significant role in the narrative shift process, and the available data show a growing public engagement with the issue. Between January 2009 and December 2019, more than 11.6 million social media posts were generated making reference to the death penalty, capital punishment, and related terms, averaging roughly 88,000 posts per month. The first significant spike occurred in September 2011 preceding and following the execution of Troy Davis in Georgia.[10] Overall online engagement with the death penalty began a steady and sustained increase beginning in March 2015, reaching a peak in July 2019 when the Trump Department of Justice announced its plan to resume executions after an almost two decade de facto moratorium.

There were significant developments in the cultural field as well, most notably the publication of Bryan Stevenson’s book Just Mercy, recounting the racist railroading and eventual release from Alabama’s death row of his client, Fred McMillian. The book remained on The New York Times best seller list for more than a year, selling more than a million copies. A film based on the book, starring Michael B. Jordan and Jamie Foxx, was released in December 2019 to critical acclaim.

CONCLUSION

Slow but steady progress characterizes the narrative shift when it comes to the death penalty. Armed with a proactive communications strategy based on fundamental American values (in this case, fairness) this case study shows that advocates can change the story even when the dominant narrative is firmly embedded in the public consciousness.

The power of the new narrative was on display in the nationwide campaign to win a stay of execution for Rodney Reed, an African American man sentenced to death by an all white jury in Texas in 1998. Reed, who has always maintained his innocence, was scheduled to be executed on November 20, 2019, but an outpouring of public support won him an indefinite stay of execution so that he could introduce new evidence of prosecutorial misconduct. In the weeks leading up to the execution, nearly 3 million people signed a petition to stop it, and celebrities including Kim Kardashian, Beyonce, QuestLove, and Oprah Winfrey spoke out. Supporters protested outside Gov. Abbott’s mansion, and the governor received pleas from the Catholic Bishop of Austin, the European Union, and the American Bar Association. On November 8, 26 bipartisan members of the Texas House of Representative sent a letter to the governor seeking a reprieve to allow for DNA testing, followed by a similar call by a bipartisan group of 16 Texas state senators. On November 10, the Houston Chronicle published an editorial that opened with the simple declarative: “Don’t kill, wait.”

On November 15, just days before the scheduled execution, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, in what the press called a “stunning decision” and a “dramatic turn of events” issued an indefinite stay, directing the Bastrop County district court to review Reed’s claims that prosecutors suppressed exculpatory evidence and presented false testimony and that he is actually innocent. The campaign to spare Rodney Reed from the busiest death chamber in the country has amplified the narrative that the death penalty is fatally flawed.

In his 1972 concurring opinion in Furman v. Georgia, Justice Thurgood Marshall wrote, “Assuming knowledge of all the facts presently available regarding capital punishment, the average citizen would, in my opinion, find it shocking to his conscience and sense of justice.” Thirty years ago, the abolition movement set itself the task of educating the “average citizen” about the many flaws in the application of the death penalty, but the ultimate goal was always to “shock the conscience” to the point where the average citizen would find it morally unacceptable. Since 2001, the Gallup’s annual Values and Beliefs Survey has been asking the following question: “Do you believe that in general the death penalty is morally acceptable or morally wrong?” In 2019 60 percent said they still believed it was morally acceptable. Although still a majority belief, the percentage has dropped 10 points since 2005.

1 Furman v. Georgia was brought by the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund.

2 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_vAKvlsKXHs

3 The Opportunity Agenda, “A New Sensibility: An Analysis of Public Opinion Research on Attitudes Towards Crime and Criminal Justice,” pp. 40–41. This publication can be found at www.opportunityagenda.org/explore/resources-publications/new-sensibility.

4 According to the NCADP’s publication, “A 30th Anniversary History,” 26 organizations comprised the new coalition at its birth. In addition to the ACLU, they included, most notably, the Southern Poverty Law Center, American Friends Service Committee, NAACP LDF, U.S. Jesuit Conference, United Presbyterian Church, and National Conference of Black Lawyers.

5 The NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund (LDF) represented an African American man sentenced to death in Georgia for killing a white police officer during a robbery. On appeal, LDF presented the Court with statistical evidence showing that racial bias played a role in the state’s capital punishment system: African Americans were more likely to receive a death sentence, and African American defendants who killed white victims were the most likely to be sentenced to death. In a 5-4 decision, the Court held that the “racially disproportionate impact” shown by the statistics was not enough to overturn the guilty verdict without showing a “racially discriminatory purpose.”

6 By the end of the 1990s, eight people on death row had been exonerated and released as a result of DNA testing.

7 A writ of habeas corpus allows a defendant (now called the petitioner) to raise many issues that cannot be raised in an appeal because a writ is not limited to re-arguing points that were raised and lost below.

8 There was a brief uptick in support following 9/11.

9 New York Times/CBS News Poll on Race Relations in the U.S., July 23, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/07/23/us/document-new-york-timescbs-news-poll-on-race-relations-in-the-us.html. A 2019 poll of North Carolina voters showed that a majority (57 percent) believed it was likely that racial bias affected whether or not a person received a death sentence.

12 The execution of Troy Davis, who maintained his innocence, received massive media coverage and was highly controversial. World figures, including Pope Benedict XVI and former U.S. President Jimmy Carter, human rights groups, and commentators urged the execution to be halted.