ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

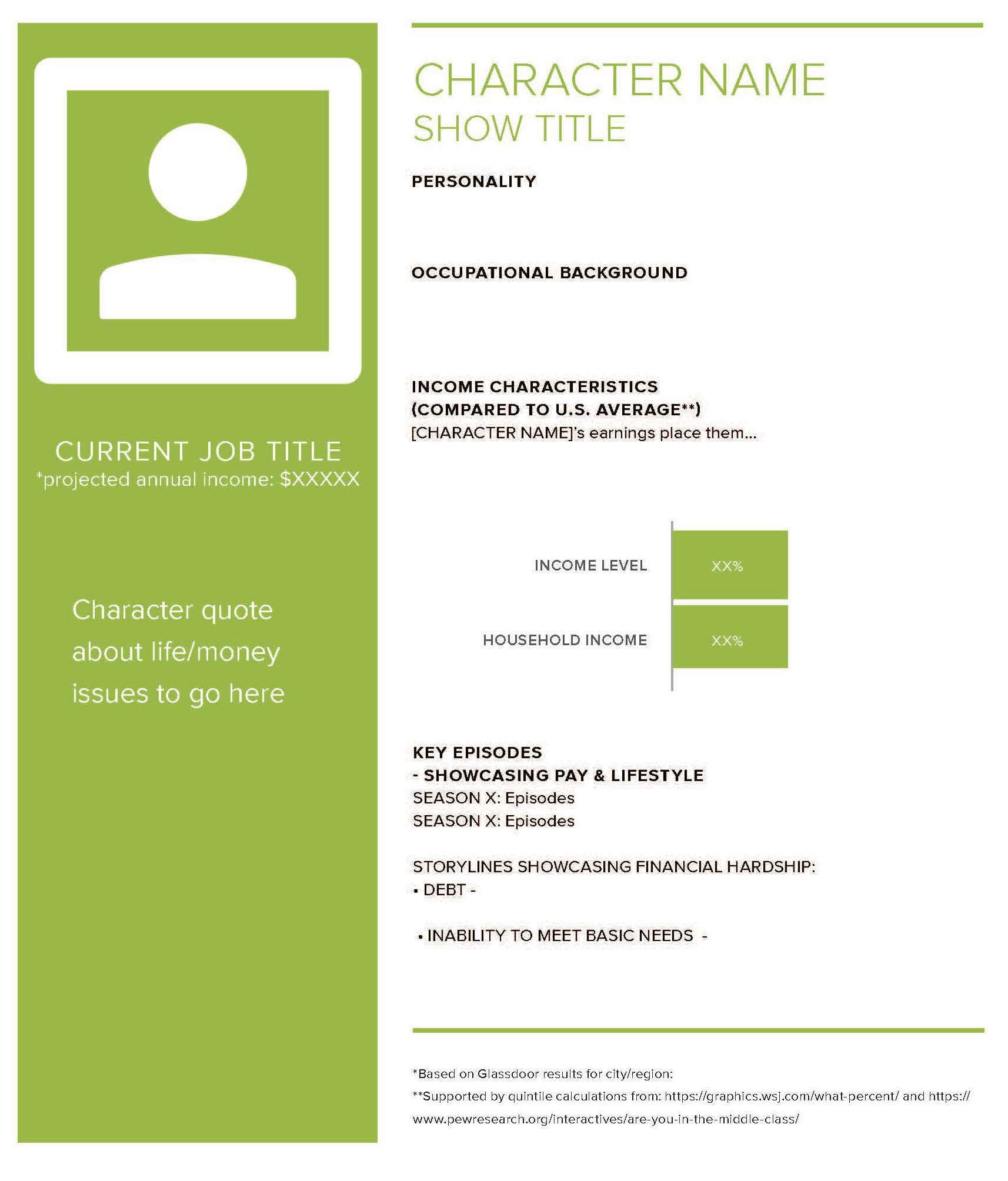

The Opportunity Agenda wishes to first acknowledge the decades of activism that have led to the prominence of the movement to fully invest in healthy communities, which includes the labor and thought leadership of many Black feminists, and to thank and acknowledge the many people who contributed to the history of work and discourse, as well as to the research and writing of this report.

This report’s author is Opportunity Agenda Law & Policy Fellow I. India Thusi, Associate Professor of Law at Delaware Law School. Substantial research support was provided by: Mitch McCloy, Washington and Lee University School of Law class of 2021; Kristen Rosenthal, California Western School of Law class of 2021; and Paul Schochet, St. John’s University School of Law class of 2021. The messaging guidance was written by Julie Fisher Rowe, Director of Narrative and Engagement at The Opportunity Agenda, and Eva-Marie Malone, Director of Training and Criminal Justice at The Opportunity Agenda. Special thanks to those who contributed to the analysis, review, and editing of the report, including Eva-Marie Malone; Adam Luna, Vice President for Program, Strategy and Impact at The Opportunity Agenda. Additional thanks go to Christiaan Perez, Manager of Media Strategy, for outreach support. This report was designed and produced by Lorissa Shepstone and Gordon Clemmons of Being Wicked. Production was coordinated by Elizabeth Johnsen, Outreach and Editorial Director at The Opportunity Agenda. Sarah Wasko created the original artwork on the cover of the report. Overall guidance was provided by The Opportunity Agenda’s President, Ellen Buchman.

Finally, this research would not have been possible without the generous support of The Joyce Foundation, The Annie E. Casey Foundation, The Ford Foundation, and the W.K. Kellogg Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely those of The Opportunity Agenda.

BEYOND POLICING – SUPPORTING #DEFUNDTHEPOLICE

We all deserve to live in communities where we feel safe. And true community safety means feeling safe from violence by the state, which includes the police.

Social inequity has systematically and institutionally permeated our country since its founding, becoming more visible at various times in our history. We are now living in one of those moments of tremendous clarity, and it calls on us to look deeply at the efficacy of the reforms and narratives which preceded it. The deadly consequences of political decisions that create health disparities are now a wound that cannot be unseen as the COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately ravages Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities. At the same moment, Americans of all backgrounds are bearing witness to the pervasive nature of racism in this country as we watch a seemingly endless stream of viral videos of police officers and white supremacist vigilantes murdering Black people.

This storm of violence, awareness, and anger about racial injustice has energized a new social justice movement to address police violence. Protesters around the world have taken to the streets chanting “Defund the Police” and “Black Lives Matter” to eradicate the ongoing threat of police violence. In light of the growing acknowledgment that policing has been an institution that compromises the safety of marginalized communities, the political will to re-imagine the very essence of community safety is growing.

Society must move beyond police and punishment when thinking about community safety, so that we can enjoy solutions and interventions that promote dignity, humanity, anti-racism, and freedom from fear.

Beyond Policing reveals that calls to enact moderate policing reforms are not backed up by a track record of success. Instead, the analysis shows why calls to defund the police open doors to new solutions, which show promise and move beyond the police and punishment. It is intended as a tool for advocates and policymakers to talk about the importance of defunding the police and investing in communities. Beyond Policing includes:

- A 13 city analysis of police departments that have adopted moderate reforms to improve policing but have nevertheless continued to engage in police violence. Our analysis provides support for the #DefundthePolice movement’s acknowledgment that it is past time to look beyond the old reforms and old ways of communicating about police reform.

- A detailed look at numerous community groups and programs that enhance community safety without relying on police involvement. These programs adopt restorative justice, community empowerment, peer mediation, and economic support to address and prevent harm. They provide concrete solutions that address the question, “If not police, then what?”

- Tips for talking about #DefundthePolice, including guidance for supporting a narrative that recognizes that the demand is realistic and needed in this moment.

WHY CALLS FOR “MODERATE POLICE REFORMS” ARE NOT ENOUGH

Advocates are calling for policymakers to #DefundthePolice because many moderate reforms, such as bans on chokeholds and the use of body-worn cameras, that are typically suggested—and often implemented— after incidents of police violence have failed to systemically transform the practice of policing.

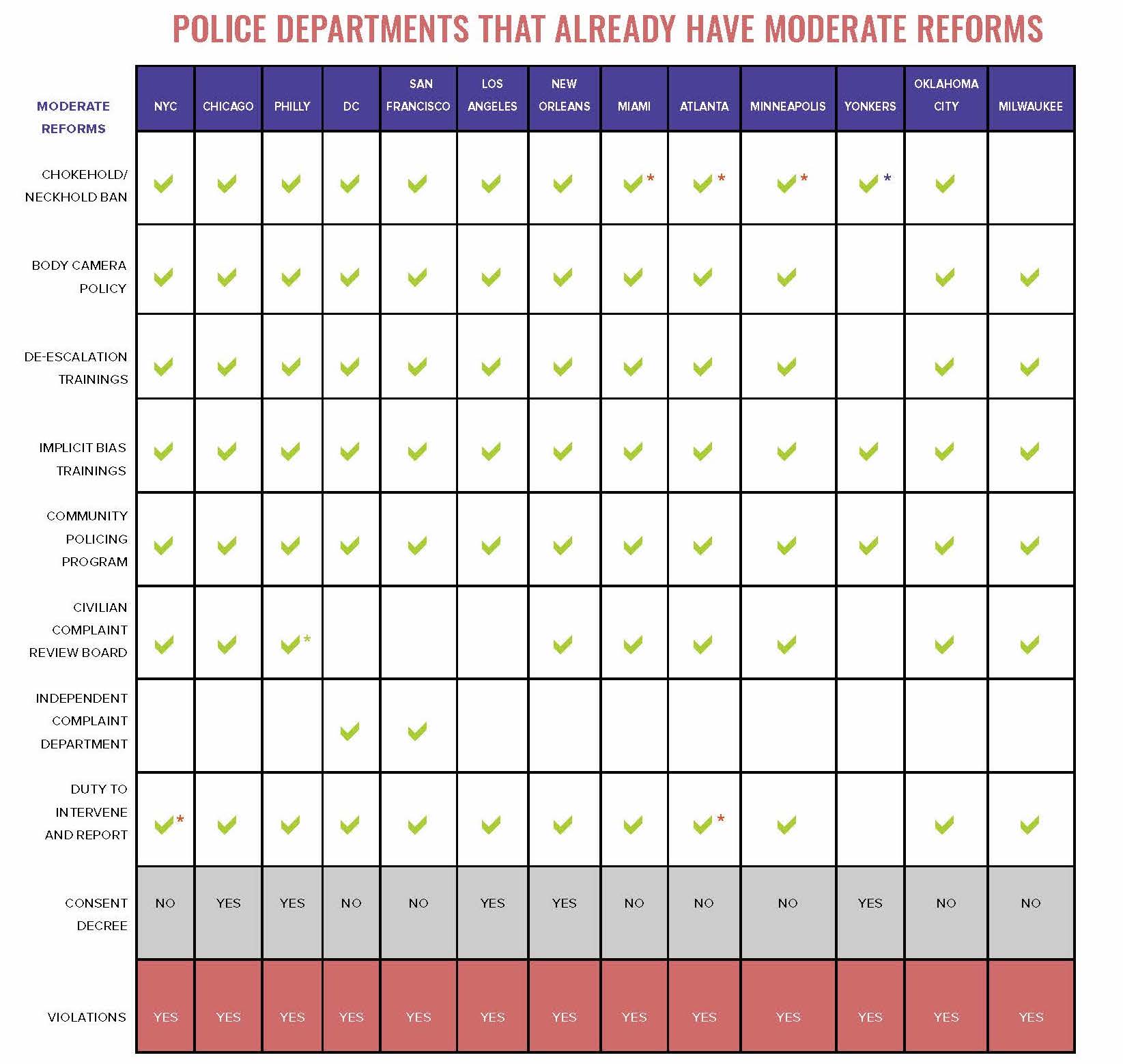

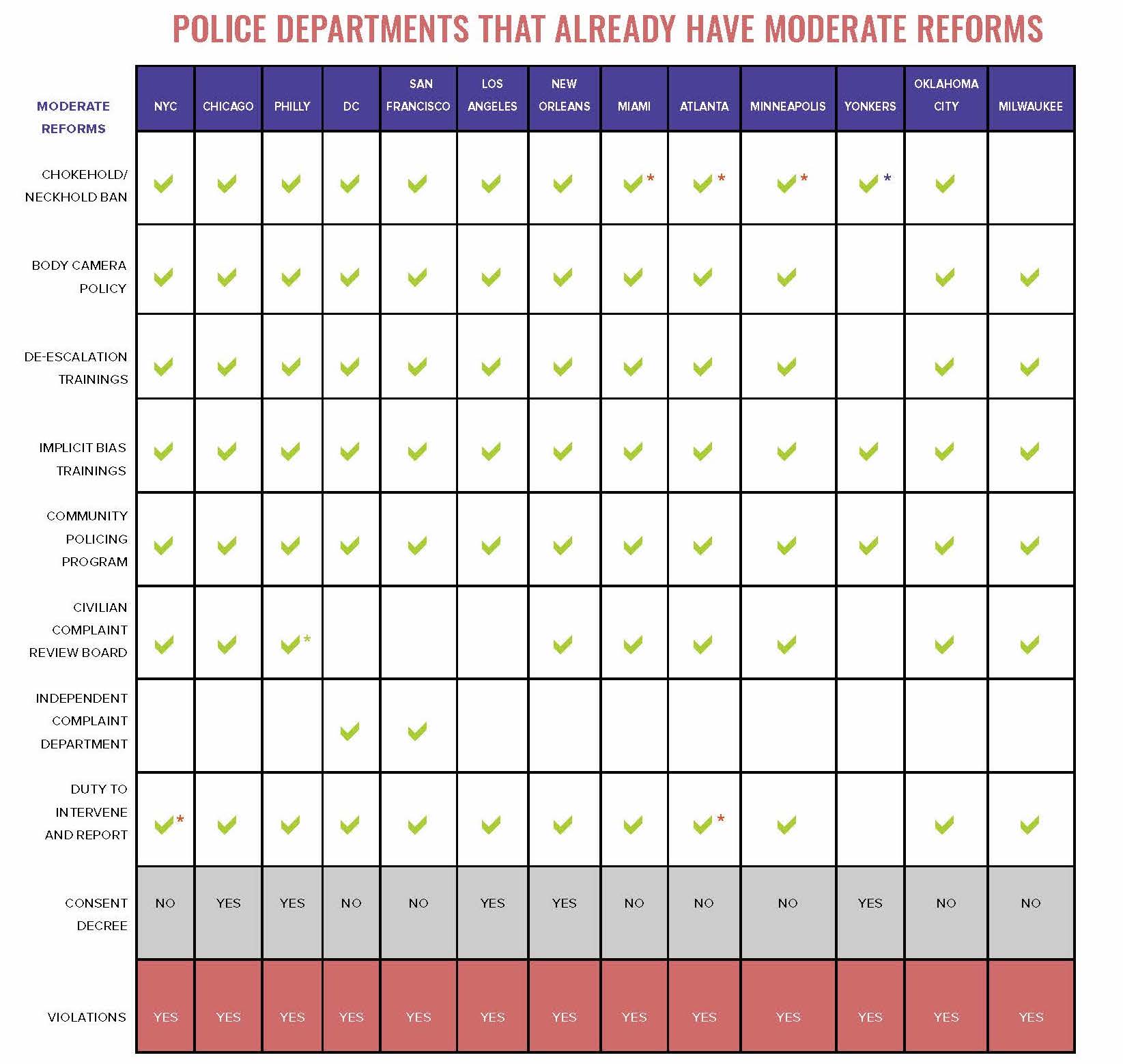

We conducted a survey of existing police department policies in 13 cities to illustrate how these policies have not led to the elimination of pervasive police violence and discriminatory policing. We looked at the policies of the police departments in New York City; Chicago; Philadelphia; Washington, DC; San Francisco; Los Angeles; New Orleans; Miami; Atlanta; Minneapolis; Yonkers; Oklahoma City; and Milwaukee. We compared: (1) bans on chokeholds, (2) de-escalation trainings, (3) implicit bias trainings, (4) “community policing” programs, (5) civilian complaint review boards, (6) body cameras, and (7) duty to intervene and/or report.

We found that the selected police departments have adopted the vast majority of the moderate policing reforms. Every city, except Milwaukee, has adopted a ban on chokeholds.1 Likewise, every city except for Yonkers has adopted a body-camera-wearing policy,2 a de-escalation training course,3 and a duty to intervene against or report misconduct by a fellow officer.4

In addition, all the cities adopted implicit bias training5 and a community policing program.6 Finally, with the exception of Yonkers, each city has an independent department for complaints or civilian complaint review board to evaluate police misconduct.7

In sum, moderate police reform policies have already been adopted across the country.

MODERATE POLICE REFORM POLICIES HAVE ALREADY BEEN ADOPTED ACROSS THE COUNTRY

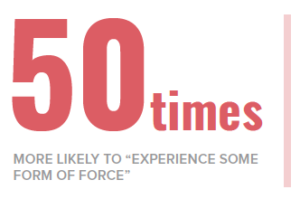

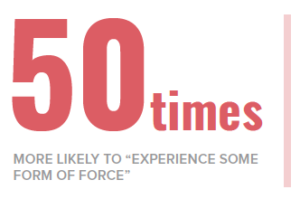

The prevalence of these policies in police departments suggests that moderate reform policies have failed to eliminate systematic police violence. Systemic racial disparities in police enforcement have continued as well. One study found African Americans were nearly three times more likely to die at the hands of police officers than white Americans.8 African Americans are similarly overrepresented in arrest rates. Indeed, in one study of more than 800 jurisdictions across the country, African Americans were five times more likely to be arrested.9 And once arrested, African Americans are, according to one study, 50 times more likely to “experience some form of force.”10 These disparities continue unabated even as departments have adopted the moderate policies that some commentators are suggesting as a response to the ongoing policing crisis.

In some cases, the civil rights violations by officers have been severe enough to require federal intervention. Specifically, cities have entered into “consent decrees” with the federal government, a court order where the city agrees to take or refrain from certain actions.11 Of the cities covered by this memorandum, Chicago, Philadelphia, New Orleans, Yonkers, and Los Angeles (for the county sheriff’s department) are subject to some federal supervision.12

The need for federal intervention and the failure to reverse systemic disparities reveal the limits of moderate reforms. Some of the limits are practical. Implicit bias training, for instance, is helpful, but it is unlikely to change a new officer with a preexisting racial bias.13 Some of the limits are institutional. Duties to report and intervene when another officer is engaging in unauthorized acts of violence are helpful. Yet such requirements cannot overcome ingrained cultures of silence among officers, especially when strong police unions stand ready to fight any accusation against an officer.14 Officers in Buffalo and Chicago, for instance, were fired for reporting a fellow officer’s misconduct.15 Other limits include legal doctrines that shield officers, qualified immunity chief among them.

Yet all these policies share a common thread: they depend on officer buy-in. And officers are buying in. This resistance to reform has been pronounced with body camera requirements. According to a New York City Civilian Complaint Review Board investigation, officers would tip each other off when they had a camera on16 and in Chicago, officers often either did not wear or turn on their body cameras.17 Given these violations, it should come as no surprise that the use of body cameras has shown no statistical impact on a reduction in force.1

Following that trend, the near-uniform ban on chokeholds across the country actually seemed to increase the use of force. In fact, a review by the New York City Civilian Complaint Review Board in 2014 found the practice on the rise.19 And this “banned” technique has caused the death of multiple victims, including Eric Garner, James Thompson, and Gerald Arthur.20 The resistance to the chokehold ban has become so prevalent in Washington, DC, that city legislatures felt compelled to pass a new law to strengthen the ban.21

Moderate reforms have failed to curb racially disparate treatment by police across the country. These policies have been met by resistance and sabotage by the departments the policy is meant to restrain. Thus, cities should look to more systemic change to end racially disparate treatment by the police. Acting under that frame of change, Berkeley, California, recently replaced officers at traffic stops with unarmed, city employees.22 Other police departments across the country should follow Berkeley’s lead by adopting policies that look beyond police for public safety. The following chart outlines the various moderate policies that the selected police departments have already adopted. Advocates can use this chart to respond to the “Why Defund the Police?” question.

The chart below suggests that we need to move beyond the same old reforms if we want to promote true community safety.

* POST-GEORGE FLOYD’S DEATH

* Yonkers police to test body cam program for 90 days in response to the George Floyd killing. https://www.lohud.com/story/news/2020/08/17/yonkers-launch-pilot-police-body-camera-program-thursday/3376672001/.

* Philadelphia has the Philadelphia Police Advisory Commission https://www.phila.gov/departments/police-advisory-commission/.

LOOKING BEYOND POLICE TO PROMOTE TRUE COMMUNITY SAFETY

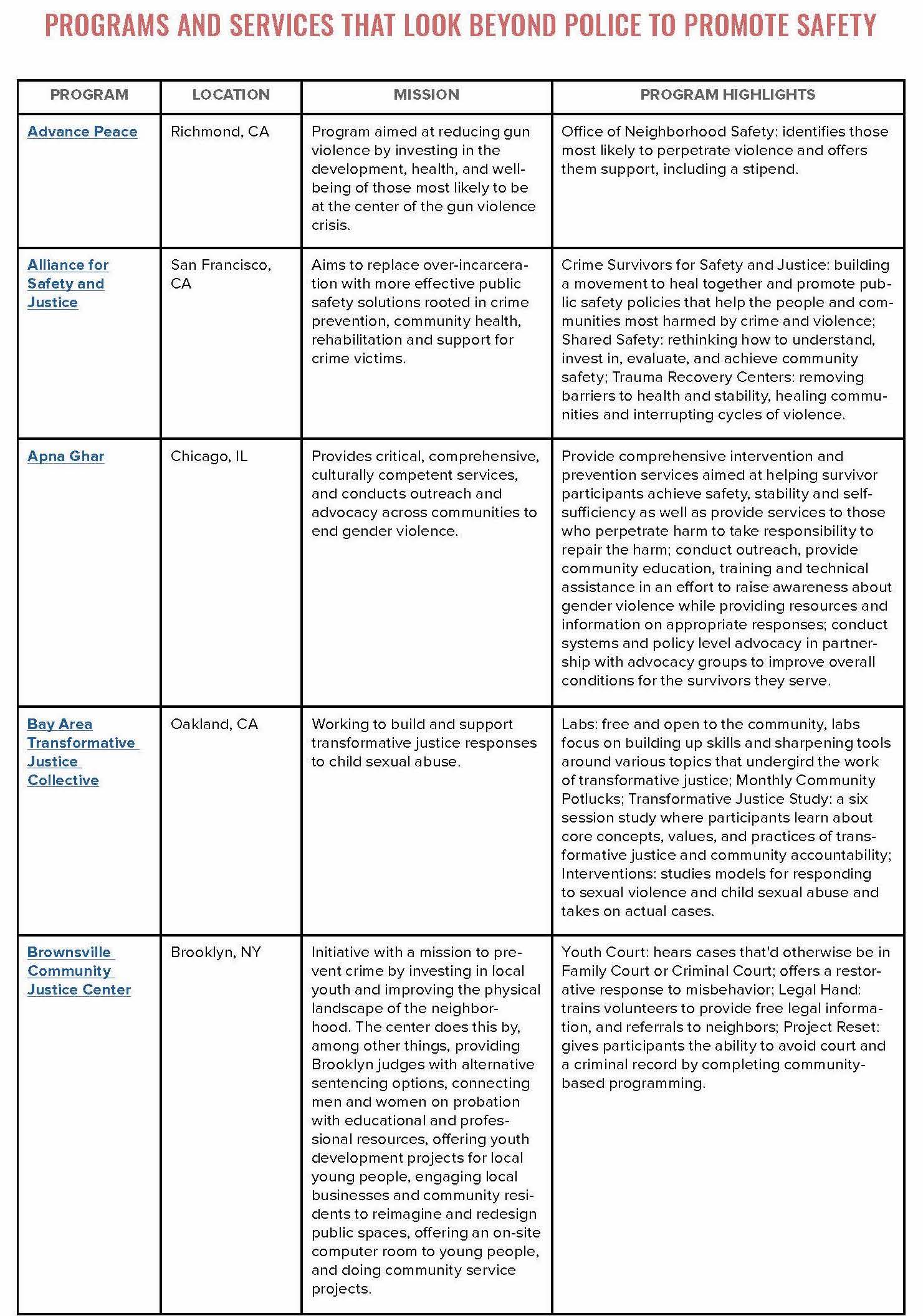

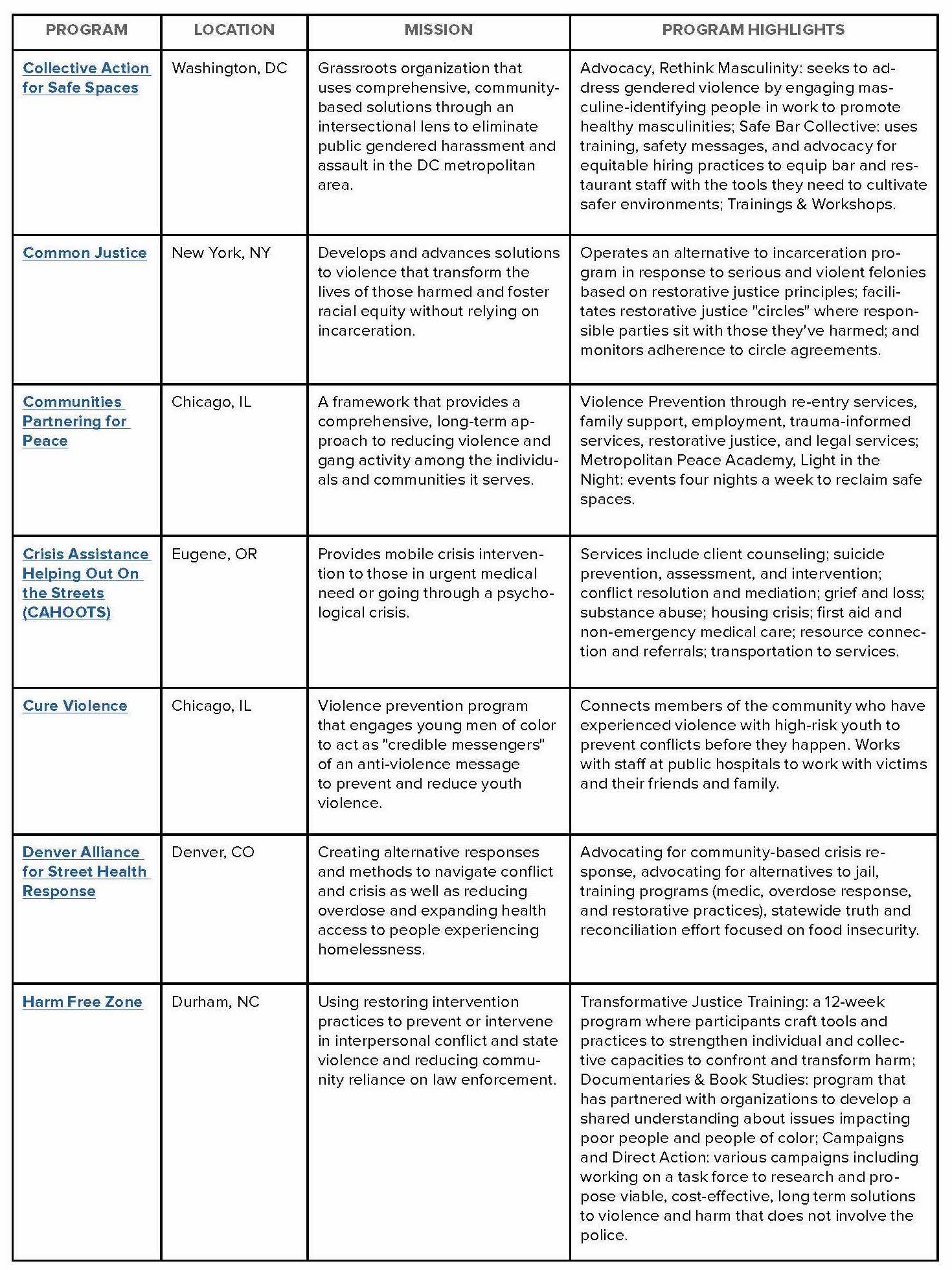

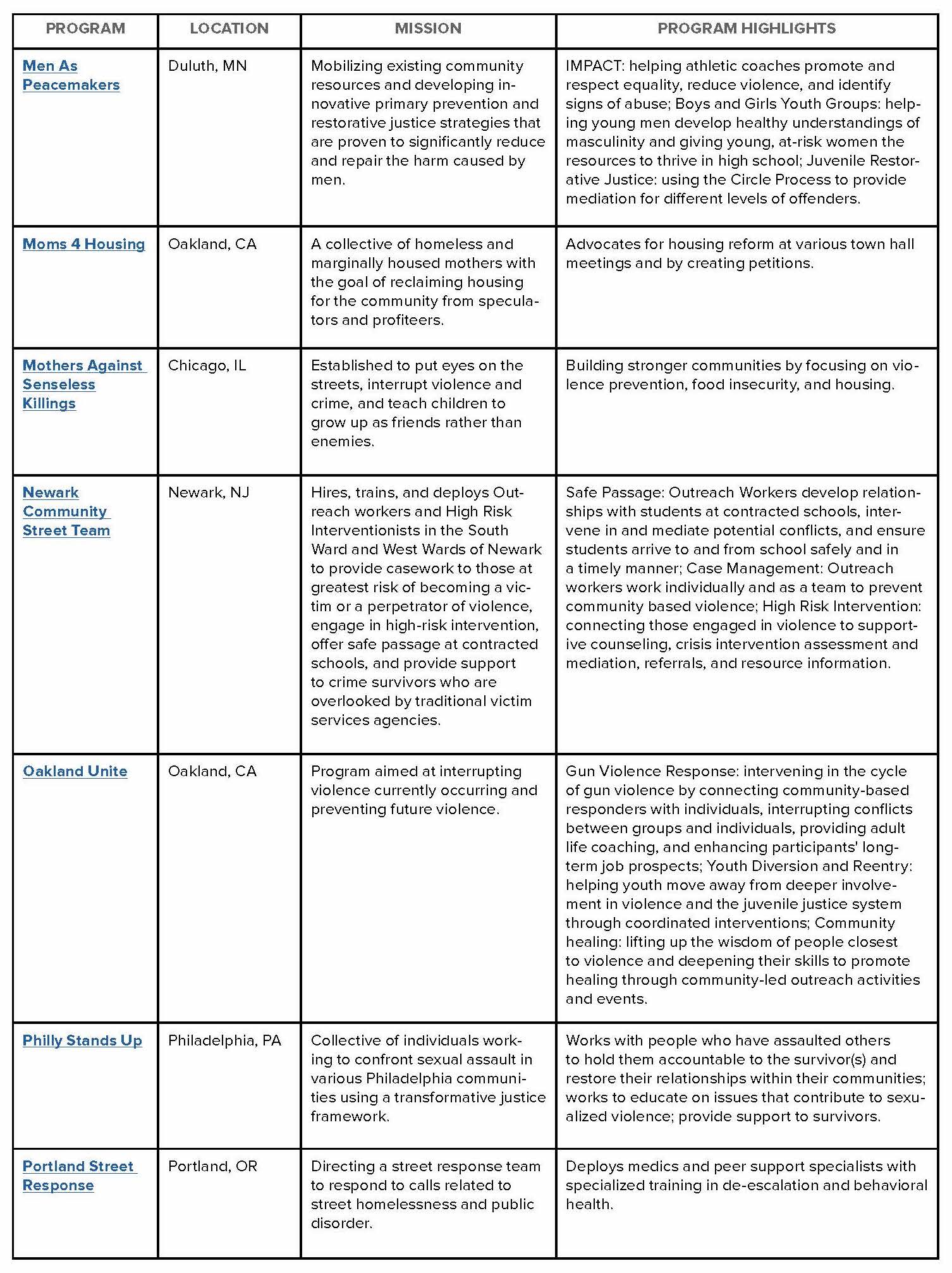

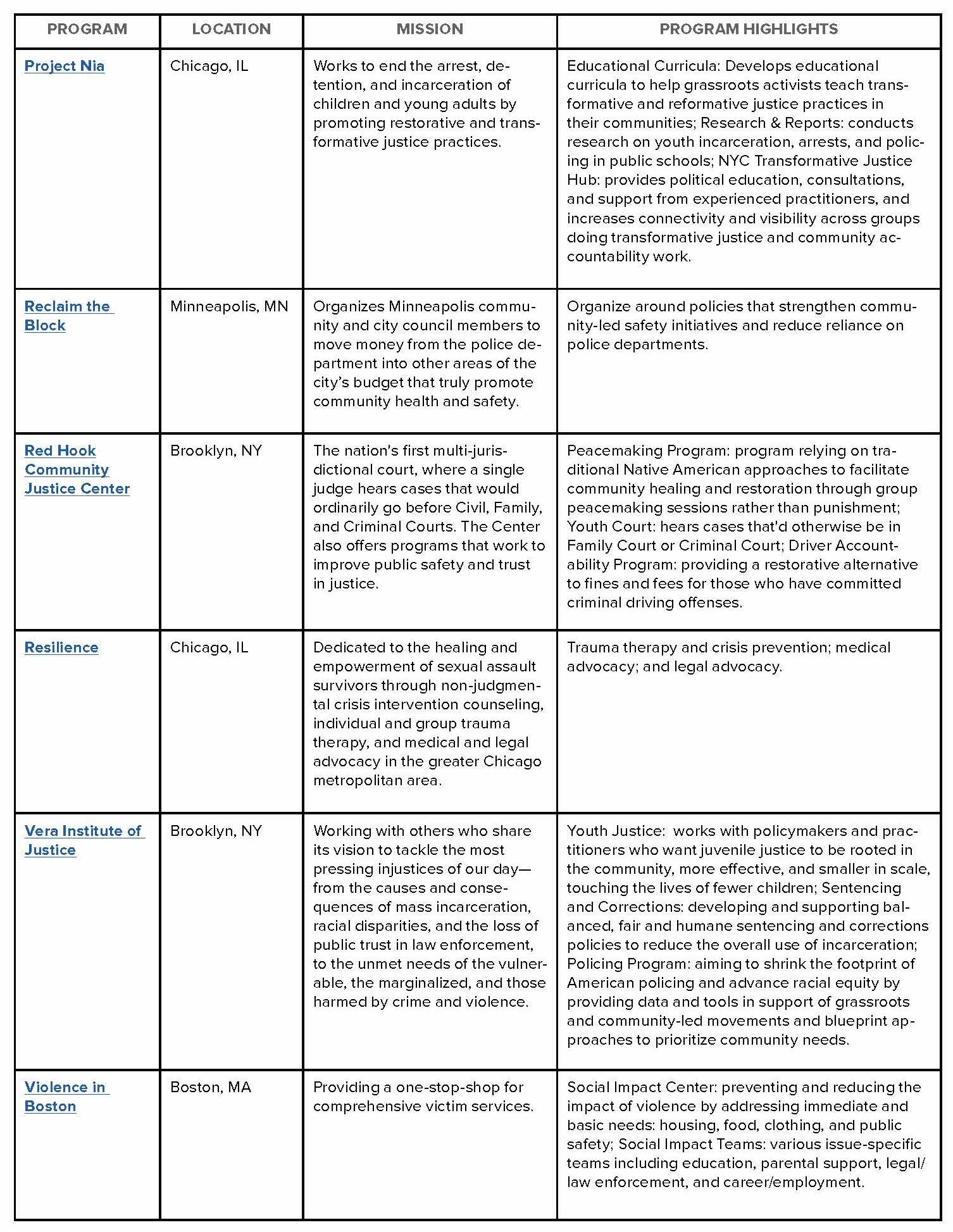

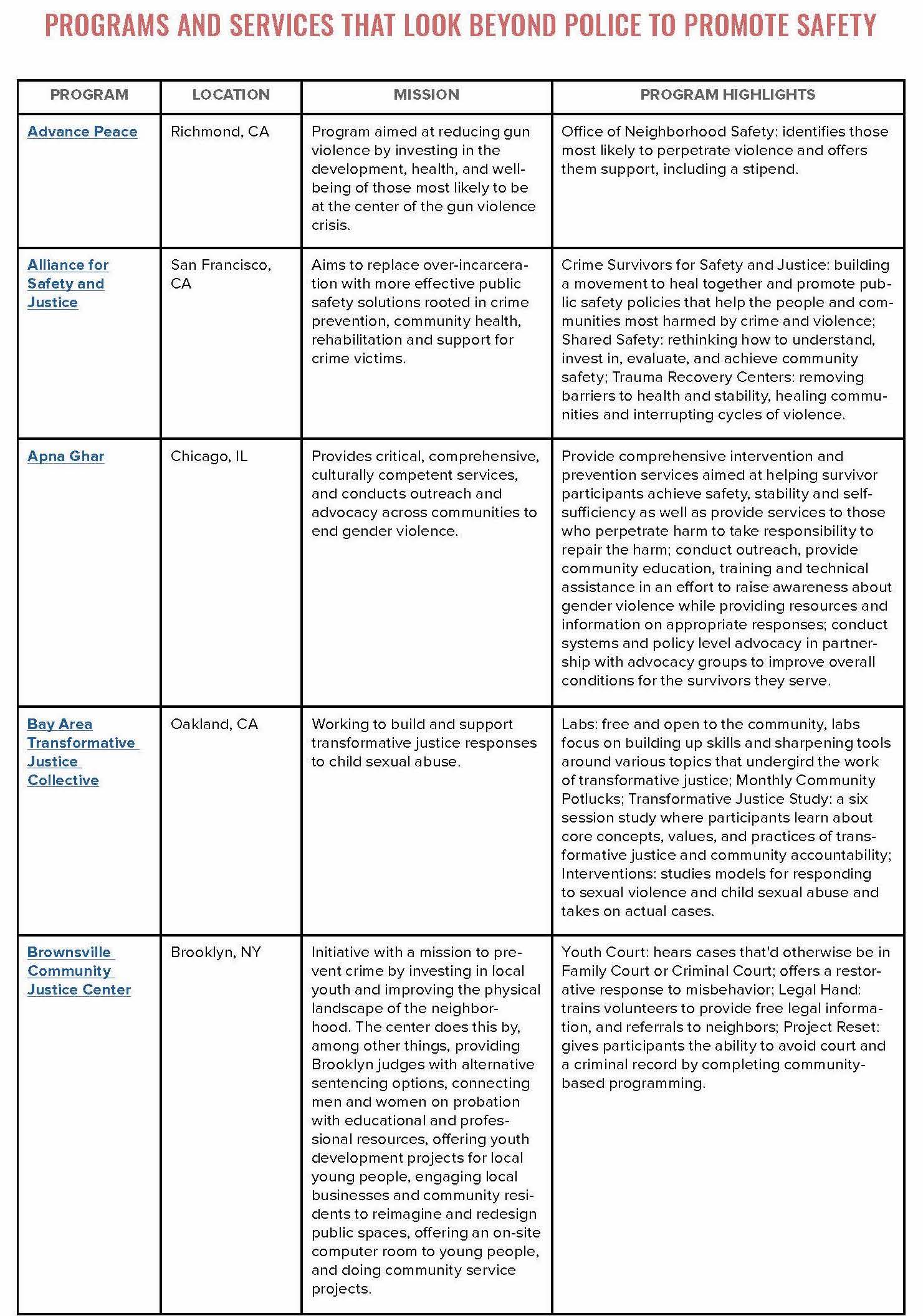

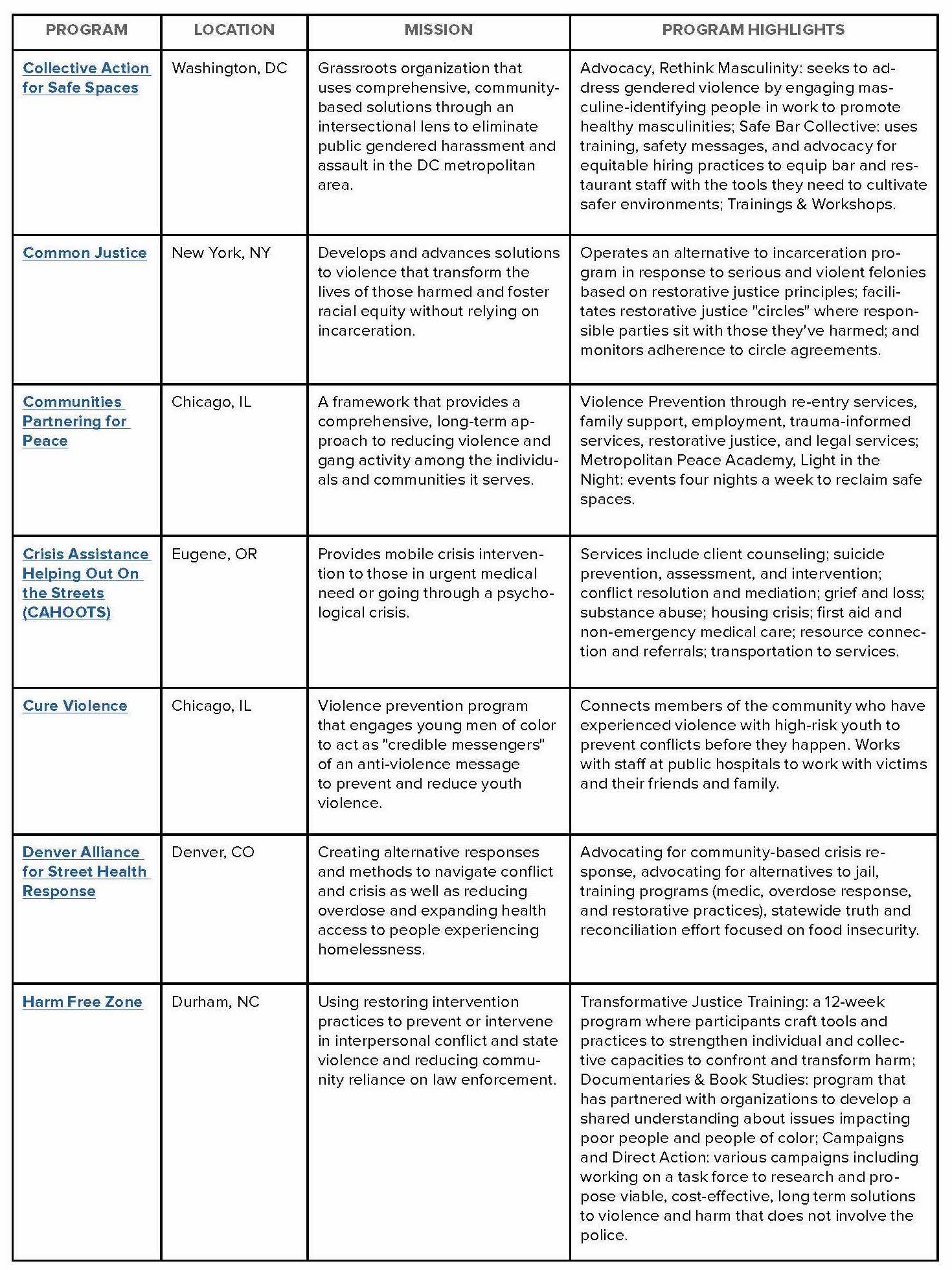

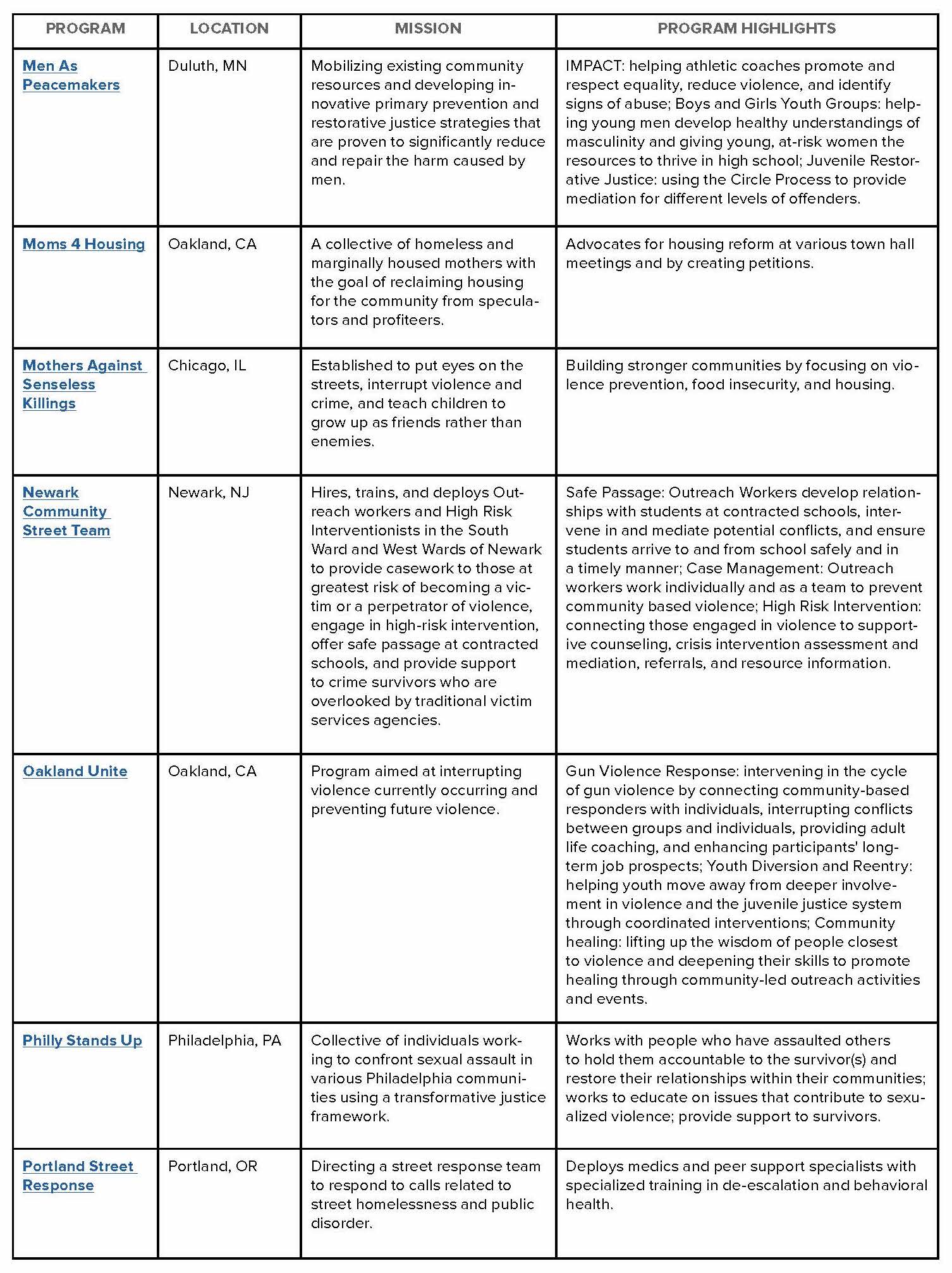

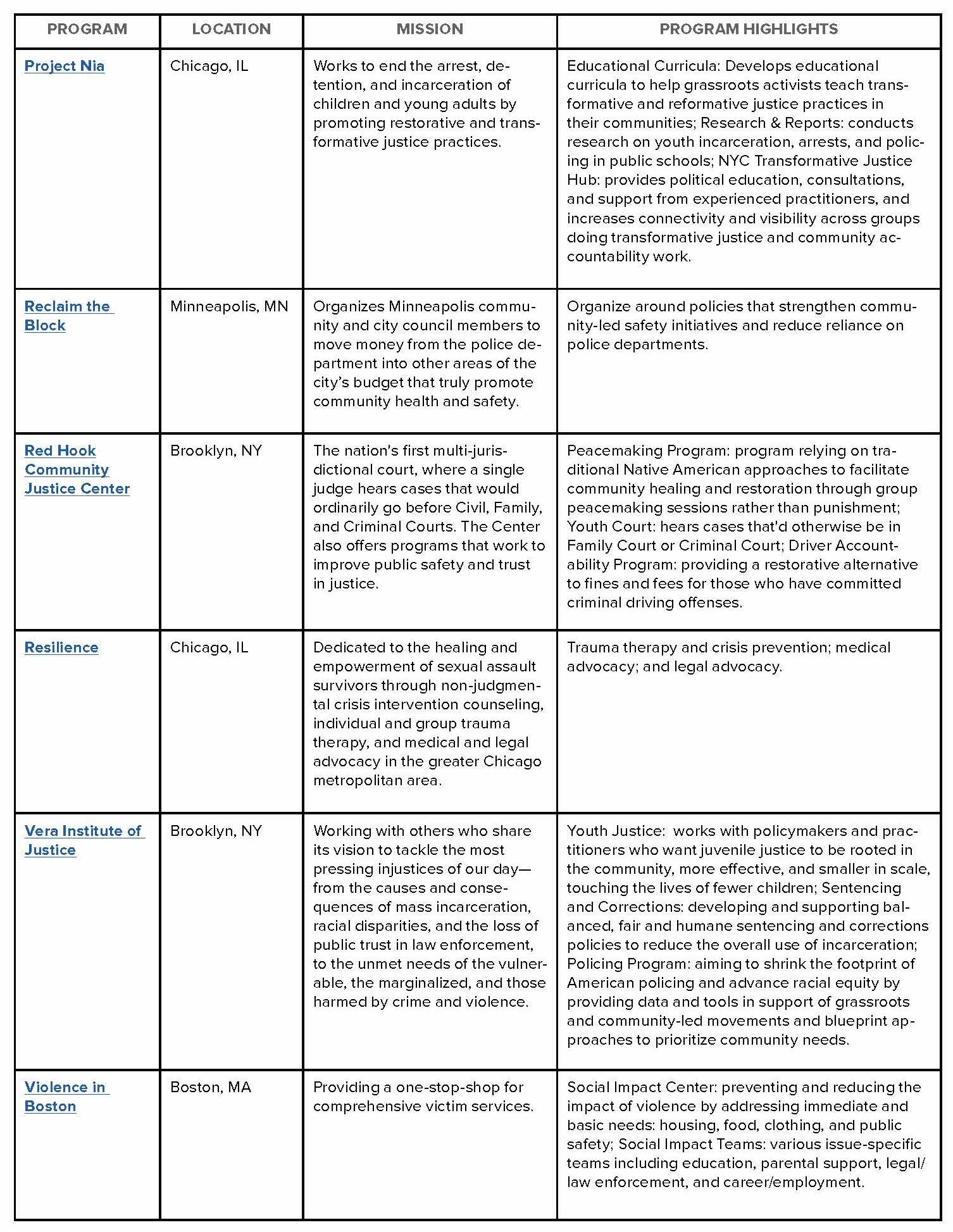

Below is a list of programs and organizations that look beyond policing to promote true community safety. It aims to assist advocates with addressing the question, “If no police, then what?” The techniques surveyed here include the use of violence interrupters, peacemaking circles, mobile crisis intervention systems, the use of stipends, and youth and community courts. The featured programs are illustrative of the potential of a model of community safety that redirects resources from the police to programs that aim to provide true community safety.

RESTORATIVE JUSTICE

Restorative justice organizations with violence interrupter programs employ local members from the community who have experienced violence themselves to connect with young adults to stop violence before it happens.113 Violence interrupters and other community-based outreach workers use their “personal relationships, social networks, and knowledge of their communities to dissuade specific individuals and neighborhood residents in general from engaging in violence.”114 After connecting with high-risk individuals, the program links youth with needed services.115 Organizations with this type of program include Cure Violence, Oakland Unite, the Newark Community Street Team, and the Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective. In October 2017, the John Jay College of Criminal Justice released a study of two Cure Violence programs located in the South Bronx and in Brooklyn.116 The study included analysis of a variety of metrics, including the reduction in social norms that support violence and violent acts. In terms of social norms, the study found that propensity to use violence in petty disputes declined by 20%.117 Overall, young men in neighborhoods with Cure Violence and violence interrupters reported “sharper reductions in their willingness to use violence compared with young men in similar areas without programs.”118

When it came to gun violence, the study found that gun injury rates fell by 50% in the Brooklyn neighborhood with Cure Violence, whereas injury rates only fell by 5% in a Brooklyn neighborhood without Cure Violence.119 In the area of the South Bronx with Cure Violence, gun injuries declined by 37% and shooting victimizations fell by 63%, compared with 29% and 17% in an area of Harlem without Cure Violence.120 Overall, the study concluded that Cure Violence’s approach to violence reduction “may help to create safer and healthier communities.”121

PEACEMAKING CIRCLES

Many restorative justice organizations now use a Native American traditional approach to justice: peacemaking circles. Circles include disputants as well as their family members, friends, and other members of the community, giving them the chance to resolve the dispute but also heal relationships among those involved.122 A number of restorative justice organizations have a peacemaking circle program, including the Red Hook Community Justice Center, the Brownsville Community Justice Center, Philly Stands Up, Common Justice, and Men As Peacemakers.

Several qualitative studies of programs implemented in schools and by restorative justice organizations reveal the beneficial impact peacemaking circles have had on participants. For example, a study focusing on two Chicago schools that used peacemaking circles found that peace circles “effectively provide young people a nonjudgmental, safe, and trusting space to express themselves” and serve as “effective sites of social and emotional learning.”123 A study of the Red Hook Community Justice Center’s peacemaking program showed more mixed results, but generally participants positively responded to the program and felt like they were making progress with the dispute.124 Victims, however, were generally less likely to say the program had a positive impact on them.125 Nevertheless, peacemaking circles can serve as an effective way to resolve disputes through community-led efforts.

MOBILE CRISIS CENTERS

Mobile crisis centers modeled after Eugene, Oregon’s Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets (CAHOOTS) program are promising alternatives to policing. Established in 1989, CAHOOTS is a “community-based public safety system to provide mental health first response for crises involving mental illness, homelessness, and addiction.”126 Rather than deploy police officers, mental health specialists respond to situations to “ensure a nonviolent resolution of crisis situations.”127 In 2019 alone, CAHOOTS responded to 24,000 calls and only requested police backup 150 times.128 In terms of cost, CAHOOTS saves the city of Eugene around $8.5 million every year in public safety costs.129 The CAHOOTS budget of $2.1 million is a fraction of the size of the Eugene and Springfield police departments, which have an annual budget of around $90 million.130

Other cities have responded by implementing their own mobile crisis programs, including Portland, which just last month approved the budget for Portland Street Response.131 Organizations in other cities like Denver are currently advocating for the establishment of mobile crisis centers.132

STIPENDS WITH ADVANCE PEACE

Advance Peace has implemented one of the more unique but encouraging programs to resolve gun violence that does not rely on the police. Upon learning that 70% of shootings in Richmond, California, were caused by 17 people, Advance Peace created a program to identify the most potentially lethal men, invite them to a meeting, and offer to pay them a monthly stipend of up to $1,000 for a maximum period of 9 months to attend meetings, stay out of trouble, and respond to mentoring.133 Advance Peace’s founder explained the reasoning behind the stipend in a New York Times op-ed: “The social context for our prospective fellows was a laundry list of deprivation and dysfunction: high unemployment, fragmented families, inadequate education and a heavy dose of substance abuse.”134 Compared to the massive amount of money spent on law enforcement and prisons used to respond to gun violence, the stipend is modest.135

After 6 years of the program, 94% of the program fellows were still alive, 84% had not sustained a gun-related injury or been hospitalized for one since becoming fellows, and 79% had not been arrested or charged for gun-related activity since becoming fellows.136 After just the first year of the program, Richmond homicides fell by half, from 45 to 22.137

YOUTH AND COMMUNITY COURTS

Community courts are part of a larger “problem-solving courts” movement that “seeks to prevent crime by directly addressing its underlying causes” rather than simply relying on punishment to address social issues.138 The nation’s first community court was established in Manhattan in 1993 as a way to relocate justice from courts to the local community, aiming to encourage communities to enforce social norms, and now there are at least 70 community courts around the world.139 Distinguishing features of community courts include individualized justice through wider access to information about defendants, expanded sentencing options, varying mandate length, offender accountability, community engagement, and community impact.140 Community courts, unlike other problem-solving courts, do not specialize in one particular problem like drugs, mental health, or domestic violence.

In November 2013, the National Center for State Courts released an extensive evaluation of the Red Hook Community Center’s community court in Brooklyn. The study found that adult misdemeanor offenders who went through the community court were to a “statistically significant degree less likely to become recidivists” than adult misdemeanor offenders in a control group.141 The probability of rearrests for offenders that went through the community court reduced by 10%.142 In addition, although the study could not definitively conclude that there was a causal relationship between the opening of the Community Center and a reduction in local arrests, there were “sharp decreases in the levels of both felony and misdemeanor arrests in the catchment area precincts” when the Center opened.143 Overall, the study concluded that “the community court model can indeed reduce crime and help to strengthen neighborhoods” and “the practice of procedural justice in interactions with individual representatives of the justice system…comprise[s] highly effective criminal justice policies.”144

THE COMMUNITY COURT MODEL CAN INDEED REDUCE CRIME AND HELP STRENGTHEN NEIGHBORHOODS

This evaluation of one particular community court falls in line with the results of other studies including an Urban Institute report conducted in 2002. This report focused on youth teen courts in Alaska, Missouri, Arizona, and Maryland and concluded that “teen courts represent a promising alternative for the juvenile justice system” after finding that youth who were sent to teen court were less likely to re-offend than youth in comparison groups.145 Nevertheless, community courts should not be used to expand the reach of the criminal system, nor should they be the primary basis for providing social welfare services. Instead, they should be viewed as an alternative when interaction with the criminal system would otherwise be required.

When it comes to community safety and justice, no one size fits all: each community’s needs are unique and each responds differently to efforts to resolve complicated issues like violence. However, there are effective alternative ways to improve community safety that do not involve the police. The programs outlined here reveal the powerful impact that restorative justice methods can have on communities in terms of both their ability to directly address issues like violence and their potential to strengthen communities as a whole by relying on community members to serve as active participants in community safety.

…THERE ARE EFFECTIVE ALTERNATIVE WAYS TO IMPROVE COMMUNITY SAFETY THAT DO NOT INVOLVE THE POLICE.

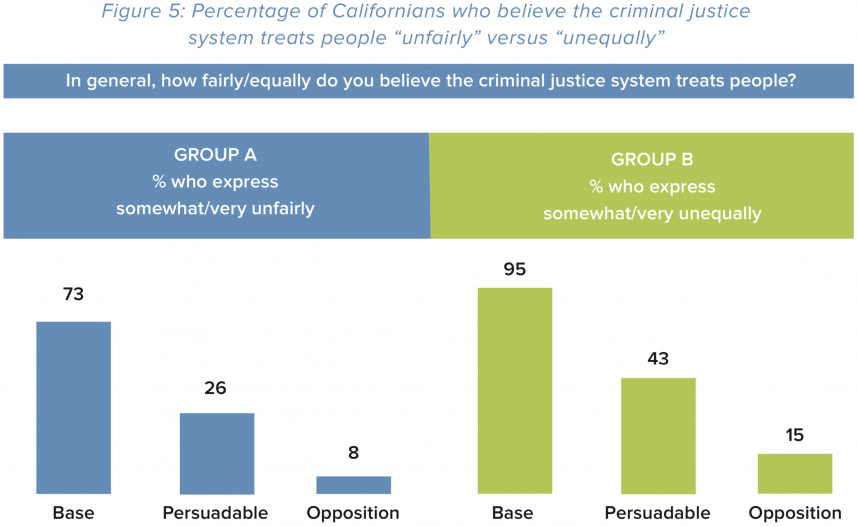

SHIFTING TO A NARRATIVE ABOUT TRUE COMMUNITY SAFETY

The Opportunity Agenda believes that any conversation about policing practices must start with the aspiration to redefine safety and for communities that can live without fear. Below is a guide to shifting to a narrative about true community safety and away from one rooted in state violence.

1. Lead with a Positive Vision and Shared Values.

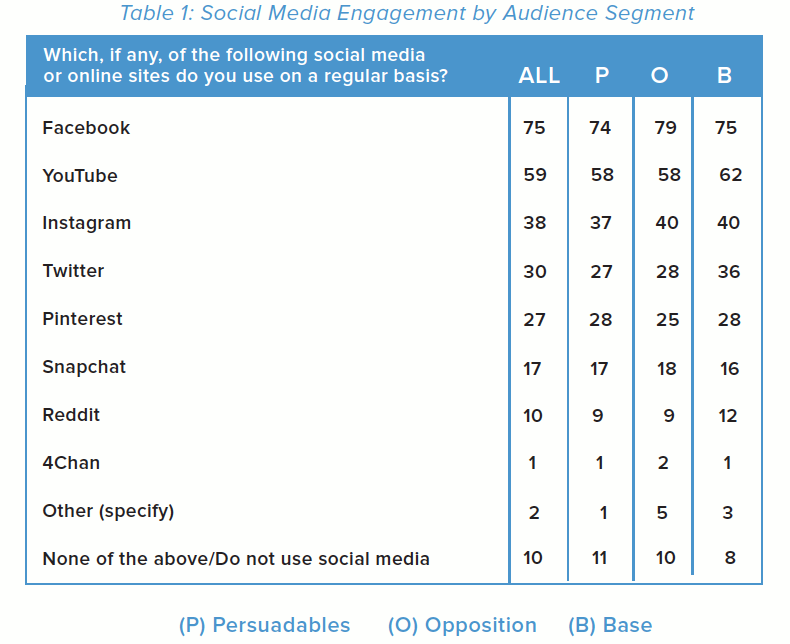

The Opportunity Agenda’s past analysis shows that commentators are often divided about how they discuss criminal justice issues. Uplifting the values that you share with different audiences will allow them to “hear” what you’re saying. Most communicators agree: people don’t change their minds based on facts alone, but rather based on how those facts are framed to fit their emotions and values.

Share a clear and inspiring vision. In many cases, audiences have a difficult time envisioning what a different system would look like. Offer a vision that both shows how a new approach will uphold our values and what that could concretely look like. What would it look like to have first responders who were unarmed mental health specialists work with those experiencing a crisis in public? How would it be different for those experiencing homelessness if they had an ongoing relationship with a trained social worker instead of periodic encounters with police? Paint a clear picture for audiences that shows what defunding looks like and how it benefits the larger community while also protecting those most currently affected by problematic policing policies.

Be prepared to answer tough questions, but don’t dwell on them. Many who are opposed to the idea of defunding the police, or who don’t fully understand the vision it represents, will start with the toughest questions: “What happens when someone is murdered?” “How should we handle school shooters?” and so on. It’s important to have a strategy for these questions and to not appear to dodge them. Then, you can move on to the larger part of the argument that affects far more people: what the country would look like with more and better mental health services, enough affordable housing and robust anti-homelessness programs, and well-funded schools, for instance.

Evoke shared values. Some values to engage audiences in conversations about policing include:

- Equal Justice—the assurance that what you look like, the accent you have, or how much money you make should not affect the treatment you receive in our justice system. Current disparities in the application of laws violate this value, and the emphasis on policing and punishment has contributed heavily to these disparities.

- Community—the notion that we share responsibility for each other and that opportunity is not only about personal success but about our success as a people. Define what a truly healthy and safe community looks like and remind audiences that we can use the resources we expend on policing to promote our shared values by enhancing health and education and protecting family.

- True Community Safety—the belief that we all want to live in communities where our family and property are safe. We should work toward communities where all individuals feel safe and paint a picture of what that can look like and what steps will get us there.

- Voice—the idea that we should all have a say in the decisions that affect us and our communities.

- Basic Rights/Human Rights—the guarantee of dignity and fairness we all deserve by virtue of our humanity, some of which are also itemized in the Constitution.

2. Clearly identify and describe the problem. Emphasize how police violence undermines community safety.

The violence that police inflict upon Black and Brown communities is often unreported and uncounted but nevertheless very dangerous for these communities. This everyday violence may take the form of aggressive searches and verbal abuse on the streets, and it is often overlooked in crime statistics that police officials use to argue that we should rely on police to redress community harms. Remind your audience that the police themselves have undermined safety in many communities through acts of everyday violence that is often unrecorded and without witnesses.

3. Communicate that reforms that fail to name the harms of racial discrimination, namely anti-Black racism, perpetuate the status quo.

The centrality of racism to police violence is apparent, and policymakers should address this issue directly. Adopting colorblind reforms and language that fail to name racism will only continue to exacerbate the racist outcomes that persist in policing. It is time to have the tough conversation about racism in policing and to look for solutions that deal with it head on.

4. Discuss the overreliance on punitive responses to social problems.

Remind your readers about the harms of this country’s overreliance on incarceration and policing to address social issues. Emphasize that there are alternatives for addressing social issues that don’t involve punishment and incarceration, both of which can separate families, punish people for being poor, and come with collateral consequences that keep people from voting and living in public housing after they have been incarcerated.

5. Highlight the failures of moderate reforms that allow police departments to operate as business as usual.

The Opportunity Agenda has provided charts that advocates can use to illustrate the need for transformative demands that move beyond the minor reforms of the past that have been ineffective or moderately successful. Many of these reforms direct more public dollars into the nation’s police departments.

6. Provide solutions that go beyond policing to achieve community safety.

Tell people what works. Put forward specific goals and solutions and show how they support the larger vision.

Talk about the need to re-examine our laws. What should be de-criminalized and what does that look like? How can our laws be fair, be fairly enforced, and lead to true safety?

The Opportunity Agenda chart on effective alternatives to policing (page 10) provides community programs that may serve as examples for thinking about a world that looks beyond police for community safety. Advocates can use this chart to respond to questions about how to provide safety while taking resources away from the police.

7. Be cautious when discussing data and statistics.

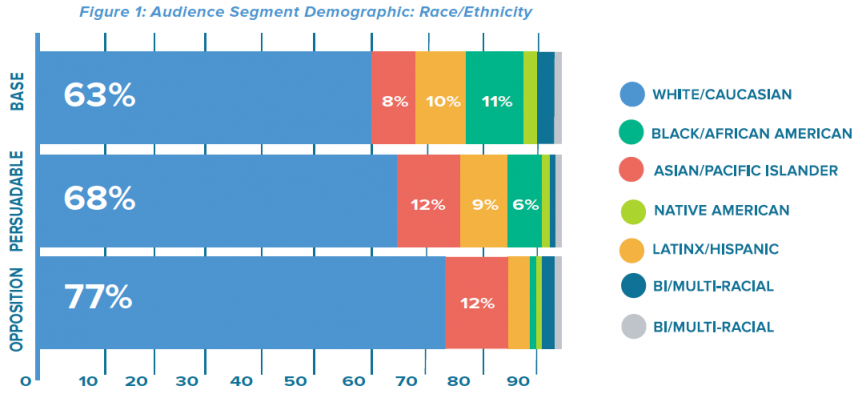

Make sure to frame racial disparities in statistics and data as caused by systemic obstacles to equal opportunity and equal justice. For some audiences, disparities that are not properly framed as the result of systemic obstacles may only reinforce racist views that those audiences already had about why those disparities exist. Explain how systemic biases affect all of us and prevent us from achieving our full potential as a country. We can never truly become a land of opportunity while we allow racial inequity to persist. And ensuring equal opportunity for all is in our shared interest.

8. Redefine the notion of community safety.

Don’t shy away from conversations about safety. #DefundthePolice is about providing safety for everyone and doing so in a manner that respects everyone’s rights and dignity. It’s about well-resourced communities that feel empowered. The goal is to achieve True Community Safety that is centered on empowering communities rather than punishing them.

9. Don’t forget the importance of staying intersectional.

It’s important to keep the conversation intersectional. At times, there can be a tendency to only focus on Black men and boys when talking about police violence. But it’s important to remind your audiences that Black women and girls have experienced unique harms from police violence in this country, as have Black trans people, indigenous women, and others. In addition, people with disabilities, mental health issues, and other communities that have experience with systemic discrimination should remain a part of the conversation.

10. Emphasize the uniqueness of this moment, and invite audiences to imagine a world that matches our values as a society.

We are at a unique moment of our history. Now is the time for us to use our imagination to create the world we would like to see.

BONUS

Call out the fear-based narratives that our opponents will use to undermine the movement.

The call to #DefundthePolice is a call to fundamentally shift power from the police to the community. It is a radical demand, and advocates should expect strong opposition to it. Some of the opposition may come through direct responses to the demand. But much of the opposition will likely come through the manipulation of crime statistics, threats that the police will not enforce the law, and other indirect tactics to stoke fear. Call out these fear-based tactics and narratives for what they are. Remind your audiences that #DefundthePolice is about providing True Community Safety.

VPSA: VALUES, PROBLEMS, SOLUTIONS, ACTION

Value

We all deserve to live in communities where we feel safe. And true community safety means being safe from violence from members of the government, including the police.

Problem

Americans have witnessed the pervasive nature of racism in this country from the steady stream of videos of police officers and vigilantes murdering Black people. These videos demonstrate that racism permeates policing and cannot be addressed by tinkering with the system.

Solution

It’s time for policymakers to defund the police and readjust local budgets to provide resources back to the communities. In NYC, the New York City Council should reallocate $1 billion from the NYPD budget to education, healthcare, and social services for the city’s low-income communities.

Action

Call your city council representative.

REFERENCES

Mariame Kaba, Yes, We Literally Mean Abolish the Police, The New York Times

- Suggesting community care workers replace officers when responding to mental health checks as well as recommending restorative justice groups.

Mariame Kaba and Shira Hassan, Fumbling Towards Repair

- A workbook on facilitating restorative justice groups.

Mariame Kaba and Kelly Hayes, A Jailbreak of the Imagination: Seeing Prisons for What They Truly Are and Demanding Transformation, Truthout.org

- Discusses how rhetoric in response to prison abolition sometimes demands answers for the most extreme cases that there is not necessarily an answer to instead of the vast majority of cases, and how advocates should not feel pressured to answer those questions and should continue to critique the current system.

- “Questions like, ‘what about the really dangerous people?’ are not questions a prison abolitionist must answer in order to insist the prison industrial complex must be undone. These are questions we must collectively answer, even as we trouble the very notion of ‘dangerousness.’ The inability to offer a neatly packaged and easily digestible solution does not preclude offering critique or analysis of the ills of our current system.”

Mariame Kaba, Free Us All: Participatory defense campaigns as abolitionist organizing, The New Inquiry

- Highlighting the importance of defense campaigns as a part of the abolitionist movement, especially for advocating for the freedom of survivors of gender-based violence. Includes a helpful list of ideas to keep in mind when organizing.

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California

- Outlines the dilemma of the Prison Industrial Complex (PIC) in California and how California criminal justice policies were fueled in part by the PIC.

Amna K. Akbar, Toward a Radical Reimagination of Law, 93 New York University Law Review 405 (2018)

- Discussing how the police provides the “armed protection of state interests” and that the law allows for more racialized police violence. Professor Akbar argues that legal scholars should imagine change beyond the current legal bounds, influenced by the social movements driving the change that should be centered.

Allegra McLeod, Developments in the Law: Envisioning Abolition Democracy, 132 Harvard Law Review 1613 (2019)

Allegra McLeod, Prison Abolition and Grounded Justice, 62 UCLA Law Review 1156 (2015)

- Explaining that abolition is less about physically tearing down prisons and is more focused on abolishing the culture of racialized punishment.

- Discussing abolition as a positive and a negative project.

Charlotte Rosen, Abolition or Bust: Liberal Prison Reform as an Engine of Carceral Violence, The Abusable Past

- Explaining why liberal policing reform is harmful from a historical context, branching off of work by Naomi Murakawa’s The First Civil Right.

K. Agbebiyi, Sarah T. Hamid, Rachel Kuo, and Mon Mohapatra, Abolition Cannot Wait: Visions for Transformation and Radical World-Building, WEAR YOUR VOICE

- Discussing the many issues that abolition affects, including anti-white supremacy, anti-capitalism, and anti-imperialism.

INCITE! Community Accountability page.

https://incite-national.org/community-accountability/

Transformharm.org Abolition page generally.

https://transformharm.org/abolition/

1 Monika Evstatieva & Tim Mak, How Decades of Bans on Police Chokeholds Have Fallen Short, NPR (June 16, 2020), https://www.npr.org/2020/06/16/877527974/how-decades-of-bans-on-police-chokeholds-have-fallen-short; Jodie Fleischer & Rick Yarborough, DC Police Banned Neck Restraints Years Ago; Council Wants to Make Law Clear, NBC Washington, https://www.nbcwashington.com/news/local/dc-police-banned-neck-restraints-years-ago-council-wants-to-make-law-clear/2326479/; Nicholas Iovin, San Francisco Police Sue Over City’s Chokehold Ban. Courthouse News Service (Dec. 27, 2016), https://www.courthousenews.com/san-francisco-police-sue-over-citys-chokehold-ban/; Atlanta passes ban on police chokeholds, empowers citizen review board. News Break (June 6, 2020), https://www.newsbreak.com/georgia/atlanta/news/0PWvAnaK/atlanta-passes-ban-on-police-chokeholds-empowers-citizen-review-board; New Orleans Police Department Operation Manual, available at https://www.nola.gov/getattachment/NOPD/NOPD-Consent-Decree/Chapter-1-3-Use-of-Force.pdf/; Oklahoma Police Department policies, available at https://www.okc.gov/home/showdocument?id=17431; Governor Cuomo Signs Legislation Requiring New York State Police Officers to Wear Body Cameras and Creating the Law Enforcement Misconduct Investigative Office, Yonkers Tribune (June 16, 2020), https://www.yonkerstribune.com/2020/06/governor-cuomo-signs-legislation-requiring-new-york-state-police-officers-to-wear-bodycameras-and-creating-the-law-enforcement-misconduct-investigative-office; Skyler Swisher, Miami-Dade Police Department bans chokeholds, Sun Sentinel (June 11, 2020), https://www.sun-sentinel.com/local/miami-dade/fl-ne-miami-dade-neck-restraints-banned-20200611-xzpcv5m2j5dhndnl5t2onmhd7e-story.html.

2 Christina Carrega, Some NYPD officers tip each other off when body cameras are on: watchdog report. ABC (Feb. 27, 2020), https://abcnews.go.com/US/nypd-officers-tip-off-body-cameraswatchdog-report/story?id=69254245; Megan Hickey, How Often Do Chicago Police Officers Fail To Activate Their Body Cameras? It’s Hard To Know, CBS Chicago (July 30, 2019), https://chicago.cbslocal.com/2019/07/30/inspector-general-chicago-police-body-cameras/; Samantha Melamed, What happens when Philly police get body cameras—but don’t turn them on? The Philadelphia Inquirer (July 15, 2020), https://www.inquirer.com/news/philadelphia-police-body-worn-cameras-commissioner-richard-ross-20190709.html; MPD and Body-Worn Cameras. DC.gov, https://mpdc.dc.gov/page/bwc; Megan Cassidy, San Francisco police turned off body cameras before illegal raid on journalist, memo says, San Francisco Chronicle (June 18, 2020), https://www.sfchronicle.com/crime/article/San-Francisco-police-turned-off-body-cameras-15349795.php; LAPD Body-Worn Cameras, ACLU, https://www.aclusocal.org/en/campaigns/lapd-body-worn-cameras; Martin Kaste, New Orleans’ Police Use of Body Cameras Brings Benefits and New Burdens, NPR (Mar. 3, 2017), https://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2017/03/03/517930343/new-orleans-police-use-of-body-cameras-brings-benefits-and-new-burdens; Body Worn Camera Program, Miami Police (2013), https://www.miami-police.org/virtual_policing_unit.html; Equipment and Supplies Policy, available at http://www2.minneapolismn.gov/police/policy/mpdpolicy_4-200_4-200; Body-Worn Cameras, OKC.gov, https://www.okc.gov/government/social-justice/justice-and-the-law/body-worn-camera-pilot-program; Atlanta Police Department Policy Manual, available at https://www.atlantapd.org/Home/ShowDocument?id=3243; Ashley Luther, What you need to know about Milwaukee police body cameras, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel (May 23, 2018), https://www.jsonline.com/story/news/crime/2018/05/23/what-you-need-know-milwaukee-police-body-cameras/635072002/.

3 Specialized Training Section, New York City Police Department, https://www1.nyc.gov/site/nypd/bureaus/administrative/training-specialized.page; Annie Sweeney, Chicago police rolling out new, mandatory “de-escalation” training, Chicago Tribune (Sep. 17, 2016), https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-chicago-police-training-met-20160916-story.html; George Fachner & Steven Carter, Collaborative Reform Initiative: An Assessment of Deadly Force in the Philadelphia Police Department, Philadelphia Police Department https://www.phillypolice.com/assets/directives/cops-w0753-pub.pdf; Metropolitan Police Department Recognizes Crisis Intervention Officer of the Year, DC.gov, https://dbh.dc.gov/release/metropolitan-police-department-recognizes-crisis-intervention-officer-year; Improving our response to crises involving the mentally ill. San Francisco Police Department (July 15, 2020), https://www.sanfranciscopolice.org/your-sfpd/explore-department/crisis-intervention-team-cit; Community Inquiries on LAPD Training and Practice, The Los Angeles Police Department, http://www.lapdonline.org/police_commission/content_basic_view/66647; Ambria Washington, In 2016, NOPD Prioritized De-Escalation Training for New and Veteran Officers, NOPD News (Dec. 13, 2016), https://nopdnews.com/post/december-2016/in-2016,-nopd-prioritized-de-escalation-training-f/; De-escalation in High Risk Tactics, Miami Dade College, https://www.mdc.edu/justice/training-programs/training-de-escalation-high-risk-tactics.aspx; Atlanta Police Training Academy, available at https://citycouncil.atlantaga.gov/Home/ShowDocument?id=340; Minneapolis Recruitment and Training, available at http://www2.minneapolismn.gov/police/policy/mpdpolicy_2-500_2-500; Police Chief Wade Gourley, OKC.gov, https://www.okc.gov/departments/police/about-us/meet-the-chief-of-police; Recommendations. City of Milwaukee, https://city.milwaukee.gov/fpc/Collaborative-Reform-Process/Chapter-5-Use-of-Force-and-Deadly-Force-Practices/Recommendation-15.1.htm.

4 Emma Ockerman, More Police Departments Are Adopting “Duty to Intervene” Policies. But They Didn’t Save George Floyd. Vice (June 5, 2020), https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/m7jvkxmore-police-departments-are-adopting-duty-to-intervene-policies-but-they-didnt-save-george-floyd; Bernard Condon & Todd Richmond, Duty to intervene: Floyd cops spoke up but didn’t step in, Associated Press (June 7, 2020), https://apnews.com/0d52f8accbbdab6a29b781d75e9aeb01; Chicago Police Department Use of Force Policy, available at https://home.chicagopolice.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/G03-02_Use-of-Force_TBD.pdf; Philadelphia Police Department Use of Force Policy, available at https://static1.squarespace.com/static/56996151cbced68b170389f4/t/569adf51d8af100e8508cf64/1452990313758/Philadelphia+less+lethal+force.pdf; Police Complaints Board Releases Report on D.C. Police Officers’ Duty to Intervene, DC.gov (Aug. 28, 2019), https://policecomplaints.dc.gov/release/police-complaints-board-releases-report-dc-police-officers%E2%80%99-duty-intervene; San Francisco Police Department General Order on Use of Force, available at https://www.sanfranciscopolice.org/sites/default/files/Documents/PoliceDocuments/DepartmentGeneralOrders/DGO%205.01%20Use%20of%20Force%20(Rev.%2012-21-16)_0.pdf; Volume 1 of LAPD Manual, available at http://www.lapdonline.org/lapd_manual/volume_1.htm; A Newsletter Of The Police Executive Research Forum, Police Executive Research Forum (July–Sept. 2016), https://www.policeforum.org/assets/docs/Subject_to_Debate/Debate2016/debate_2016_julsep.pdf; Miami-Dade Police Department releases letter to community amid protests, Local10.com (June 8, 2020), https://www.local10.com/news/local/2020/06/08/miami-dade-police-department-releases-letter-to-community-amid-protests/; Atlanta Police Training Academy, supra note 3; Lauren Daniels, Oklahoma City Police respond to nationwide “8 Can’t Wait” campaign, Oklahoma’s News 4 (June 15, 2020), https://kfor.com/news/oklahoma-city-police-respond-to-nationwide-8-cant-wait-campaign/; Amanda St. Hilaire, What Milwaukee police policies really say (and why it matters), Fox 6 Now (June 22, 2020), https://fox6now.com/2020/06/22/what-milwaukee-police-policies-really-say-and-why-it-matters/.

5 Seth Barron, Explicit Danger, City Journal (Aug. 29, 2019), https://www.city-journal.org/implicit-bias-training; Debbie Southorn & Sarah Lazare, Officers Accused of Abuses Are Leading Chicago Police’s “Implicit Bias” Training Program, The Intercept (Feb. 3, 2019), https://theintercept.com/2019/02/03/chicago-police-procedural-justice-training-complaints-lawsuits-racism/; Kelly Cofrancisco, Breaking down the FY21 Philadelphia Police Department’s proposed budget, City of Philadelphia (June 5, 2020), https://www.phila.gov/2020-06-05-breaking-down-the-fy21-philadelphiapolice-departments-proposed-budget/; Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) Academy Sessions, Georgetown Law, https://www.law.georgetown.edu/innovative-policing-program/metropolitanpolice-department-mpd-academy-sessions/; New Orleans Police Department Operations Manual, available at https://www.nola.gov/getattachment/NOPD/Policies/Bias-Free.pdf/; Bias-Free Policing, San Francisco Police Department (updated July 15, 2020), https://www.sanfranciscopolice.org/your-sfpd/policies/bias-free-policing; Volume 1 of LAPD Manual, supra note 4; Candice Wang, Can implicit bias training help cops overcome racism? Popular Science (June 16, 2020), https://www.popsci.com/story/science/implicit-bias-training-police-racism-black-lives-matter/; Atlanta Police Training Academy, supra note 3; Riham Feshir, Minneapolis budgets $300,000 for police bias training, MPR News (Dec. 10, 2015), https://www.mprnews.org/story/2015/12/10/mpls-policebias-training; Council Majority Leader Pineda-Isaac: Repeal 50a and Body Cameras for the YPD, Yonkers Times (June 13, 2020), http://yonkerstimes.com/council-majority-leader-pineda-isaacrepeal-50a-and-body-cameras-for-the-ypd/; Matt Dinger, Oklahoma City officers take long look at themselves and citizens in bias training class, The Oklahoman (Dec. 27, 2016), https://oklahoman.com/article/5531923/oklahoma-city-officers-take-long-look-at-themselves-and-citizens-in-bias-training-class.

6 Neighborhood Policing, New York City Police Department, https://www1.nyc.gov/site/nypd/bureaus/patrol/neighborhood-coordination-officers.page; Chicago Police Department Strategic Plan, available at https://home.chicagopolice.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Chicago-Police-Department-Strategic-Plan-Plan-2019-January.pdf; Philadelphia Police Collaborative Reform Initiative, available at https://www.phillypolice.com/assets/directives/cops-w0792-pub.pdf; MPD Community Outreach, DC.gov, https://mpdc.dc.gov/page/communityoutreach; Community Policing Strategic Plan, San Francisco Police Department (updated July 15, 2020), https://www.sanfranciscopolice.org/your-sfpd/policies/community-policing-strategic-plan; Community Policing Unit, The Los Angeles Police Department, http://www.lapdonline.org/support_lapd/content_basic_view/731; New Orleans Police Department Community Engagement Manual, available at https://www.nola.gov/getattachment/NOPD/NOPD-Consent-Decree/Community-Engagement-Manual-(3).pdf/; Community Policing, Crime Prevention, and Juvenile Programs Evaluation by Miami-Dade Police Department, available at https://www.miamidade.gov/police/library/community-policing.pdf; Reginald Moorman, Community Policing Programs, Atlanta Police Department, https://www.atlantapd.org/services/community-services/community-policing-programs; Minneapolis Community-Oriented Policing and Community Relations Training, available at http://www2.minneapolismn.gov/police/policy/mpdpolicy_6-300_6-300; Yonkers Police Department Public Opinion Survey 2017, available at https://www.yonkersny.gov/home/showdocument?id=16846; Community Programs, okc.gov, https://www.okc.gov/departments/police/community-programs; Office of Community Outreach & Education, Milwaukee Police Department, https://city.milwaukee.gov/police/MPD-Divisions/Community-Outreach-Education.htm.

7 Complaints, NYC, https://www1.nyc.gov/site/ccrb/complaints/complaints.page; Civilian Office of Policy Accountability; City of Chicago, https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/depts/copa.html; About Office of Police Complaints, DC.gov, https://policecomplaints.dc.gov/page/about-office-police-complaints; Department of Police Accountability, available at https://sfgov.org/dpa/; Mark Puente, All-civilian panels could review LAPD misconduct cases starting June 13, Los Angeles Times (June 4, 2019), https://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-police-commission-officer-board-of-rightsdiscipline-20190604-story.html; New Orleans Independent Police Monitor, available at http://nolaipm.gov/history/; Civilian Investigative Panel (CIP), MIAMI, https://www.miamigov.com/Government/Departments-Organizations/Civilian-Investigative-Panel-CIP; Atlanta Citizen Review Board, available at https://acrbgov.org/; OKCPD Citizens Advisory Board, okc.gov, https://www.okc.gov/departments/police/about-us/citizens-advisory-board; Milwaukee Fire and Police Commission, available at https://city.milwaukee.gov/fpc/About.

8 Sarah DeGue, Katherine Fowler, & Cynthia Calkins, Deaths due to use of lethal force by law enforcement: Findings from the National Violent Death Reporting System, 17 U.S. States 2009–2012. Am J Prev Med. 2016 Nov; 51(5 Suppl 3): S173–S187, available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6080222/.

9 Pierre Thomas, John Kelly, & Tonya Simpson, ABC News analysis of police arrests nationwide reveals stark racial disparity, ABC (June 11, 2020), https://abcnews.go.com/US/abc-news-analysis-police-arrests-nationwide-reveals-stark/story?id=71188546.

10 Roland G. Fryer J., An Empirical Analysis of Racial Differences in Police Use of Force, Journal of Political Economy (2017), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w22399.pdf.

11 See DECREE, Black’s Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019).

12 The Department of Justice’s Interactive Guide to the Civil Rights Division’s Police Reforms, available at https://www.justice.gov/crt/page/file/922456/download; Chicago Police Consent Decree, available at http://chicagopoliceconsentdecree.org/resources/; Aaron Mosselle, ACLU: New stop-and-frisk numbers “not what people of Philadelphia deserve,” Whyy (Apr. 28, 2020), https://whyy.org/articles/aclu-new-stop-and-frisk-numbers-not-what-people-of-philadelphia-deserve/.

13 Michael Hobbes, “Implicit Bias” Trainings Don’t Actually Change Police Behavior, HUFFPOST (Updated June 15, 2020), https://www.huffpost.com/entry/implicit-bias-training-doesnt-actually-change-police-behavior_n_5ee28fc3c5b60b32f010ed48.

14 Cf. Douglas Belkin, Kris Maher, & Deanna Paul, Clout of Minneapolis Police Union Boss Reflects National Trend, The Wall Street Journal (July 7, 2020), https://www.wsj.com/articles/robert-krolls-rise-from-barroom-brawler-to-minneapolis-police-union-boss-11594159577?mod=hp_lead_pos5.

15 Justin Sondel & Hannah Knowles, George Floyd died after officers didn’t step in. These police say they did—and paid a price, The Washington Post (June 12, 2020), https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/06/10/police-culture-duty-to-intervene/.

16 Christina Carrega, supra note 2.

17 Megan Hickey, supra note 2.

18 Ethan Zuckerman, Why filming police violence has done nothing to stop it, MIT Technology Review (June 3, 2020). https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/06/03/1002587/sousveillance-george-floyd-police-body-cams/.

19 Monika Evstatieva & Tim Mak, supra note 1.

20 Id.

21 Jodie Fleischer & Rick Yarborough, supra note 1.

22 Summer Lin, California city votes to remove cops from traffic stops, aims to slash police budget, Miami Herald (July 14, 2020), https://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/national/article244221592.html.

23 For a discussion of violations of the reform-policies by police departments, see accompanying memorandum.

24 Monika Evstatieva & Tim Mak, How Decades of Bans on Police Chokeholds Have Fallen Short, NPR (June 16, 2020), https://www.npr.org/2020/06/16/877527974/how-decades-of-bans-on-police-chokeholds-have-fallen-short.

25 Christina Carrega, Some NYPD officers tip each other off when body cameras are on: watchdog report, ABC (Feb. 27, 2020), https://abcnews.go.com/US/nypd-officers-tip-off-body-cameras-watchdog-report/story?id=69254245.

26 Specialized Training Section, New York City Police Department, https://www1.nyc.gov/site/nypd/bureaus/administrative/training-specialized.page.

27 Seth Barron, Explicit Danger, City Journal (Aug. 29, 2019), https://www.city-journal.org/implicit-bias-training.

28 Neighborhood Policing, New York City Police Department, https://www1.nyc.gov/site/nypd/bureaus/patrol/neighborhood-coordination-officers.page.

29 Complaints, NYC, https://www1.nyc.gov/site/ccrb/complaints/complaints.page

30 Emma Ockerman, More Police Departments Are Adopting “Duty to Intervene” Policies. But They Didn’t Save George Floyd, Vice (June 5, 2020), https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/m7jvkx/more-police-departments-are-adopting-duty-to-intervene-policies-but-they-didnt-save-george-floyd.

31 Monika Evstatieva & Tim Mak, supra note 57.

32 Megan Hickey, How Often Do Chicago Police Officers Fail To Activate Their Body Cameras? It’s Hard To Know, CBS Chicago (July 30, 2019), https://chicago.cbslocal.com/2019/07/30/inspector-general-chicago-police-body-cameras/.

33 Annie Sweeney, Chicago police rolling out new, mandatory “de-escalation” training, Chicago Tribune (Sep. 17, 2016), https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-chicago-police-training-met-20160916-story.html.

34 Debbie Southorn & Sarah Lazare, Officers Accused of Abuses Are Leading Chicago Police’s “Implicit Bias” Training Program, The Intercept (Feb. 3, 2019), https://theintercept.com/2019/02/03/chicago-police-procedural-justice-training-complaints-lawsuits-racism/.

35 Chicago Police Department Strategic Plan, available at https://home.chicagopolice.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Chicago-Police-Department-Strategic-Plan-Plan-2019-January.pdf.

36 Civilian Office of Policy Accountability, City of Chicago, https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/depts/copa.html.

37 Chicago Police Department Use of Force Policy, available at https://home.chicagopolice.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/G03-02_Use-of-Force_TBD.pdf.

38 Chicago Police Consent Decree, available at http://chicagopoliceconsentdecree.org/resources/.

39 Monika Evstatieva & Tim Mak, supra note 57.

40 Samantha Melamed, What happens when Philly police get body cameras—but don’t turn them on? The Philadelphia Inquirer (July 15, 2020), https://www.inquirer.com/news/philadelphia-police-body-worn-cameras-commissioner-richard-ross-20190709.html.

41 George Fachner & Steven Carter, Collaborative Reform Initiative An Assessment of Deadly Force in the Philadelphia Police Department, Philadelphia Police Department, https://www.phillypolice.com/assets/directives/cops-w0753-pub.pdf.

42 Kelly Cofrancisco, Breaking down the FY21 Philadelphia Police Department’s proposed budget, City of Philadelphia (June 5, 2020), https://www.phila.gov/2020-06-05-breaking-down-the-fy21-philadelphia-police-departments-proposed-bud get/.

43 Philadelphia Police Collaborative Reform Initiative, available at https://www.phillypolice.com/assets/directives/cops-w0792-pub.pdf; MPD Community Outreach, DC.gov, https://mpdc.dc.gov/page/communityoutreach.

44 Philadelphia Police Department Use of Force Policy, available at https://static1.squarespace.com/static/56996151cbced68b170389f4/t/569adf51d8af100e8508cf64/14529903 13758/Philadelphia+less+lethal+force.pdf.

45 Aaron Mosselle, ACLU: New stop-and-frisk numbers “not what people of Philadelphia deserve,” Whyy (Apr. 28, 2020), https://whyy.org/articles/aclu-new-stop-and-frisk-numbers-not-what-people-of-philadelphia-deserve/.

46 Jodie Fleischer & Rick Yarborough, DC Police Banned Neck Restraints Years Ago; Council Wants to Make Law Clear, NBC Washington, https://www.nbcwashington.com/news/local/dc-police-banned-neck-restraints-years-ago-council-wants-to-make-law-clear/2326479/.

47 MPD and Body-Worn Cameras, DC.gov., https://mpdc.dc.gov/page/bwc.

48 Metropolitan Police Department Recognizes Crisis Intervention Officer of the Year, DC.gov, https://dbh.dc.gov/release/metropolitan-police-department-recognizes-crisis-intervention-officer-year.

49 Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) Academy Sessions, Georgetown Law, https://www.law.georgetown.edu/innovative-policing-program/metropolitan-police-department-mpd-academy-sessions/.

50 MPD Community Outreach, DC.gov, https://mpdc.dc.gov/page/communityoutreach.

51 About Office of Police Complaints, DC.gov, https://policecomplaints.dc.gov/page/about-office-police-complaints.

52 Police Complaints Board Releases Report on D.C. Police Officers’ Duty to Intervene, DC.gov (Aug. 28, 2019), https://policecomplaints.dc.gov/release/police-complaints-board-releases-report-dc-police-officers%E2%80 %99-duty-intervene.

53 Nicholas Iovin, San Francisco Police Sue Over City’s Chokehold Ban, Courthouse News Service (Dec. 27, 2016), https://www.courthousenews.com/san-francisco-police-sue-over-citys-chokehold-ban/.

54 Megan Cassidy, San Francisco police turned off body cameras before illegal raid on journalist, memo says, San Francisco Chronicle (June 18, 2020), https://www.sfchronicle.com/crime/article/San-Francisco-police-turned-off-body-cameras-15349795.php.

55 Improving our response to crises involving the mentally ill, San Francisco Police Department (July 15, 2020), https://www.sanfranciscopolice.org/your-sfpd/explore-department/crisis-intervention-team-cit.

56 Bias-Free Policing, San Francisco Police Department (updated July 15, 2020), https://www.sanfranciscopolice.org/your-sfpd/policies/bias-free-policing.

57 Community Policing Strategic Plan, San Francisco Police Department (updated July 15, 2020), https://www.sanfranciscopolice.org/your-sfpd/policies/community-policing-strategic-plan.

58 Department of Police Accountability, available at https://sfgov.org/dpa/.

59 San Francisco Police Department General Order on Use of Force, available at https://www.sanfranciscopolice.org/sites/default/files/Documents/PoliceDocuments/DepartmentGeneralOrders/DGO%205.01%20Use%20of%20Force%20(Rev.%2012-21-16)_0.pdf.

60 Monika Evstatieva & Tim Mak, supra note 57.

61 LAPD Body-Worn Cameras, ACLU, https://www.aclusocal.org/en/campaigns/lapd-body-worn-cameras.

62 Community Inquiries on LAPD Training and Practice, The Los Angeles Police Department, http://www.lapdonline.org/police_commission/content_basic_view/66647.

63 Volume 1 of LAPD Manual, available at http://www.lapdonline.org/lapd_manual/volume_1.htm.

64 Community Policing Unit, The Los Angeles Police Department, http://www.lapdonline.org/support_lapd/content_basic_view/731.

65 Mark Puente, All-civilian panels could review LAPD misconduct cases starting June 13, Los Angeles Times (June 4, 2019), https://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-police-commission-officer-board-of-rights-discipline-2019060 4-story.html.

66 Volume 1 of LAPD Manual, supra note 96.

67 The Department of Justice’s Interactive Guide to the Civil Rights Division’s Police Reforms, available at https://www.justice.gov/crt/page/file/922456/download.

68 New Orleans Police Department Operations Manual, available at https://www.nola.gov/getattachment/NOPD/NOPD-Consent-Decree/Chapter-1-3-Use-of-Force.pdf/.

69 Martin Kaste, New Orleans’ Police Use of Body Cameras Brings Benefits and New Burdens, NPR (Mar. 3, 2017), https://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2017/03/03/517930343/new-orleans-police-use-of-body-ca meras-brings-benefits-and-new-burdens.

70 Ambria Washington, In 2016, NOPD Prioritized De-Escalation Training for New and Veteran Officers, NOPD News (Dec. 13, 2016), https://nopdnews.com/post/december-2016/in-2016,-nopd-prioritized-de-escalation-training-f/.

71 New Orleans Police Department Operations Manual, available at https://www.nola.gov/getattachment/NOPD/Policies/Bias-Free.pdf/.

72 New Orleans Police Department Community Engagement Manual, available at https://www.nola.gov/getattachment/NOPD/NOPD-Consent-Decree/Community-Engagement-Manual-(3).pdf.

73 New Orleans Independent Police Monitor, available at http://nolaipm.gov/history/.

74 A Newsletter of the Police Executive Research Forum, Police Executive Research Forum (July–Sept. 2016), https://www.policeforum.org/assets/docs/Subject_to_Debate/Debate2016/debate_2016_julsep.pdf.

75 The Department of Justice’s Interactive Guide to the Civil Rights Division’s Police Reforms, supra note 44.

76 Skyler Swisher, Miami-Dade Police Department bans chokeholds, Sun Sentinel (June 11, 2020), https://www.sun-sentinel.com/local/miami-dade/fl-ne-miami-dade-neck-restraints-banned-20200611-xzpcv5m2j5dhndnl5t2onmhd7e-story.html.

77 Body Worn Camera Program, Miami Police (2013), https://www.miami-police.org/virtual_policing_unit.html.

78 De-escalation In High Risk Tactics, Miami Dade College, https://www.mdc.edu/justice/training-programs/training-de-escalation-high-risk-tactics.aspx.

79 Candice Wang, Can implicit bias training help cops overcome racism? Popular Science (June 16, 2020), https://www.popsci.com/story/science/implicit-bias-training-police-racism-black-lives-matter/.

80 Community Policing, Crime Prevention, and Juvenile Programs Evaluation by Miami-Dade Police Department, available at https://www.miamidade.gov/police/library/community-policing.pdf.

81 Civilian Investigative Panel (CIP), Miami, https://www.miamigov.com/Government/Departments-Organizations/Civilian-Investigative-Panel-CIP.

82 Miami-Dade Police Department releases letter to community amid protests, local10.com (June 8, 2020), https://www.local10.com/news/local/2020/06/08/miami-dade-police-department-releases-letter-to-community-amid-protests/.

83 Atlanta passes ban on police chokeholds, empowers citizen review board, News Break (June 6, 2020), https://www.newsbreak.com/georgia/atlanta/news/0PWvAnaK/atlanta-passes-ban-on-police-chokeholds-empowers-citizen-review-board.

84 Atlanta Police Department Policy Manual, available at https://www.atlantapd.org/Home/ShowDocument?id=3243.

85 Atlanta Police Training Academy, available at https://citycouncil.atlantaga.gov/Home/ShowDocument?id=340.

86 Id.

87 Reginald Moorman, Community Policing Programs, Atlanta Police Department, https://www.atlantapd.org/services/community-services/community-policing-programs.

88 Atlanta Citizen Review Board, available at https://acrbgov.org/.

89 Atlanta Police Training Academy, supra note 118.

90 Monika Evstatieva & Tim Mak, supra note 57.

91 Equipment and Supplies Policy, available at http://www2.minneapolismn.gov/police/policy/mpdpolicy_4-200_4-200.

92 Minneapolis Recruitment and Training, available at http://www2.minneapolismn.gov/police/policy/mpdpolicy_2-500_2-500.

93 Riham Feshir, Minneapolis budgets $300,000 for police bias training, MPR News (Dec. 10, 2015), https://www.mprnews.org/story/2015/12/10/mpls-police-bias-training.

94 Minneapolis Community-Oriented Policing and Community Relations Training, available at http://www2.minneapolismn.gov/police/policy/mpdpolicy_6-300_6-300.

95 Minneapolis: Civilian Review, Human Rights Watch, https://www.hrw.org/legacy/reports98/police/uspo87.htm.

96 Duty To Intervene: Floyd Cops Spoke Up But Didn’t Step In, CBS Minnesota (June 7, 2020), https://minnesota.cbslocal.com/2020/06/07/duty-to-intervene-floyd-cops-spoke-up-but-didnt-step-in/.

97 Governor Cuomo Signs Legislation Requiring New York State Police Officers to Wear Body Cameras and Creating the Law Enforcement Misconduct Investigative Office, Yonkers Tribune (June 16, 2020), https://www.yonkerstribune.com/2020/06/governor-cuomo-signs-legislation-requiring-new-york-state-police-officers-to-wear-body-cameras-and-creating-the-law-enforcement-misconduct-investigative-office.

98 Repeal 50a and Body Cameras for the YPD, Yonkers Times (June 13, 2020), http://yonkerstimes.com/council-majority-leader-pineda-isaac-repeal-50a-and-body-cameras-for-the-ypd/.

99 Yonkers Police Department Public Opinion Survey 2017, available at https://www.yonkersny.gov/home/showdocument?id=16846.

100 Oklahoma Police Department policies, available at https://www.okc.gov/home/showdocument?id=17431.

101 Body-Worn Cameras, OKC.gov, https://www.okc.gov/government/social-justice/justice-and-the-law/body-worn-camera-pilot-program.

102 Police Chief Wade Gourley, OKC.gov, https://www.okc.gov/departments/police/about-us/meet-the-chief-of-police.

103 Matt Dinger, Oklahoma City officers take long look at themselves and citizens in bias training class, The Oklahoman (Dec. 27, 2016), https://oklahoman.com/article/5531923/oklahoma-city-officers-take-long-look-at-themselves-and-citizens-i n-bias-training-class.

104 Community Programs, OKC.gov, https://www.okc.gov/departments/police/community-programs.

105 OKCPD Citizens Advisory Board, OKC.gov, https://www.okc.gov/departments/police/about-us/citizens-advisory-board.

106 Oklahoma City Police respond to nationwide “8 Can’t Wait” campaign, Oklahoma’s News 4 (June 15, 2020), https://kfor.com/news/oklahoma-city-police-respond-to-nationwide-8-cant-wait-campaign/.

107 Ashley Luther, What you need to know about Milwaukee police body cameras, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel (May 23, 2018), https://www.jsonline.com/story/news/crime/2018/05/23/what-you-need-know-milwaukee-police-body-cameras/635072002/.

108 Recommendations, City of Milwaukee, https://city.milwaukee.gov/fpc/Collaborative-Reform-Process/Chapter-5-Use-of-Force-and-Deadly-Force-Practices/Recommendation-15.1.htm.

109 Candice Wang, supra note 112.

110 Office of Community Outreach & Education, Milwaukee Police Department, https://city.milwaukee.gov/police/MPD-Divisions/Community-Outreach-Education.htm.

111 Milwaukee Fire and Police Commission, available at https://city.milwaukee.gov/fpc/About.

112 Amanda St. Hilaire, What Milwaukee police policies really say (and why it matters), Fox 6 Now (June 22, 2020), https://fox6now.com/2020/06/22/what-milwaukee-police-policies-really-say-and-why-it-matters/.

113 NYC Young Men’s Initiative: Program Summary—NYC Cure Violence, City of New York, 2012 http://www.nyc.gov/html/ymi/downloads/pdf/cure_violence.pdf.

114 Sheyla Delgado, Laila Alsabahi, Kevin Wolff, Nicole Alexander, Patricia Coba, and Jeffrey Butts, The Effects of Cure Violence in the South Bronx and East New York, Brooklyn, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, October 2, 2017 https://johnjayrec.nyc/2017/10/02/cvinsobronxeastny/.

115 Id.

116 Id.

117 Id.

118 Id.

119 Id.

120 Id.

121 Id.

122 Peacemaking Program, Center for Court Innovation, https://www.courtinnovation.org/programs/peacemaking-program/more-info.

123 Michael Maly, Keeping the Peace: A Study of Restorative Justice Peace Circles in Two Chicago Public Schools, Restorative School Toolkit, Spring 2014, http://restorativeschoolstoolkit.org/sites/default/files/Keeping%20the%20Peace_Final%20Report%20Spring14_Final.pdf.

124 Suvi Hynynen Lambson, Peacemaking Circles: Evaluating a Native American Restorative Justice Practice in a State Criminal Court Setting in Brooklyn, Center for Court Innovation, January 2015 https://www.courtinnovation.org/sites/default/files/documents/Peacemaking%20Circles%20Final.pdf.

125 Id.

126 Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets: Media Guide 2020, White Bird Clinic, 2020 https://whitebirdclinic.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/CAHOOTS-Media-Guide-20200626.pdf.

127 Id.

128 Id.

129 Id.

130 Id.

131 Kaia Sand, TAKE ACTION! Petition City Council to Increase Funding for Portland Street Response, Portland Street Response, June 7, 2020 https://portlandstreetresponse.org/.

132 Work: Community-Based Crisis Response, Denver Alliance for Street Health Response, http://dashrco.org/#:~:text=Since%202018%2C%20Denver%20Alliance%20for,safety%20and%20serve%20our%20communities.

133 Devone L. Boggan, To Stop Crime, Hand Over Cash, New York Times, July 4, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/05/opinion/sunday/to-stop-crime-hand-over-cash.html.

134 Id.

135 Id.

136 A.M. Wolf, A. Del Prado Lippman, C. Glesmann, E. Castro, Process Evaluation for the Office of Neighborhood Safety, National Council on Crime and Delinquency, July 2015, https://www.advancepeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/4%E2%80%94ONS-Process-Evaluation_FINAL.July_.2015.pdf.

137 Id.

138 Cynthia G. Lee, Fred L. Cheesman, David B. Rottman, Rachel Swaner, Suvi Lambson, Mike Rempel, and Rick Curtis, A Community Court Grows in Brooklyn: A Comprehensive Evaluation of the Red Hook Community Justice Center, National Center for State Courts, November 2013, https://www.courtinnovation.org/sites/default/files/documents/RH%20Evaluation%20Final%20Report.pdf.

139 Id.

140 Id.

141 Cynthia G. Lee, Fred L. Cheesman, David B. Rottman, Rachel Swaner, Suvi Lambson, Mike Rempel, and Rick Curtis, Executive Summary: A Community Court Grows in Brooklyn: A Comprehensive Evaluation of the Red Hook Community Justice Center, National Center for State Courts, November 2013, https://www.ncsc.org/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/19113/11012013-red-hook-exeuctive-summary.pdf.

142 Id.

143 Id.

144 Id.

145 Jeffrey Butts, Janeen Buck, Mark Coggeshall, The Impact of Teen Court on Young Offenders, National Criminal Justice Reference Service, April 2002, https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/237391.pdf.