EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In The Opportunity Agenda’s Power of POP research series, we explore the impacts of pop culture vis-à-vis scripted television[1] and influencers[2] on social issues. The subject matter we address is related to our work in economic opportunity, immigration, racial justice, and democracy. By considering the leading social issues of the time within a framework of new, values-based narrative goals, we engage in study that we hope bolsters discourse.

We are currently living through a global reckoning on workers’ rights, corporate greed, and economic justice. Across the headlines, we see examples of workers, from John Deere to the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE), who are organizing and striking against exploitative corporate practices that leave them unable to maintain a cost of living or receive adequate health care and workers’ compensation. This developing narrative around what employment should look like in a post-COVID, worker-centered world is also being captured in the scripted works airing on television to mass appeal. In fact, one of the breakout hits of 2021, Squid Game, centers on a character who is traumatized by his experience in a work strike turned violent by company owners and law enforcement—reminiscent of the real-world strike of SsangYong Motor in 2009.[3]

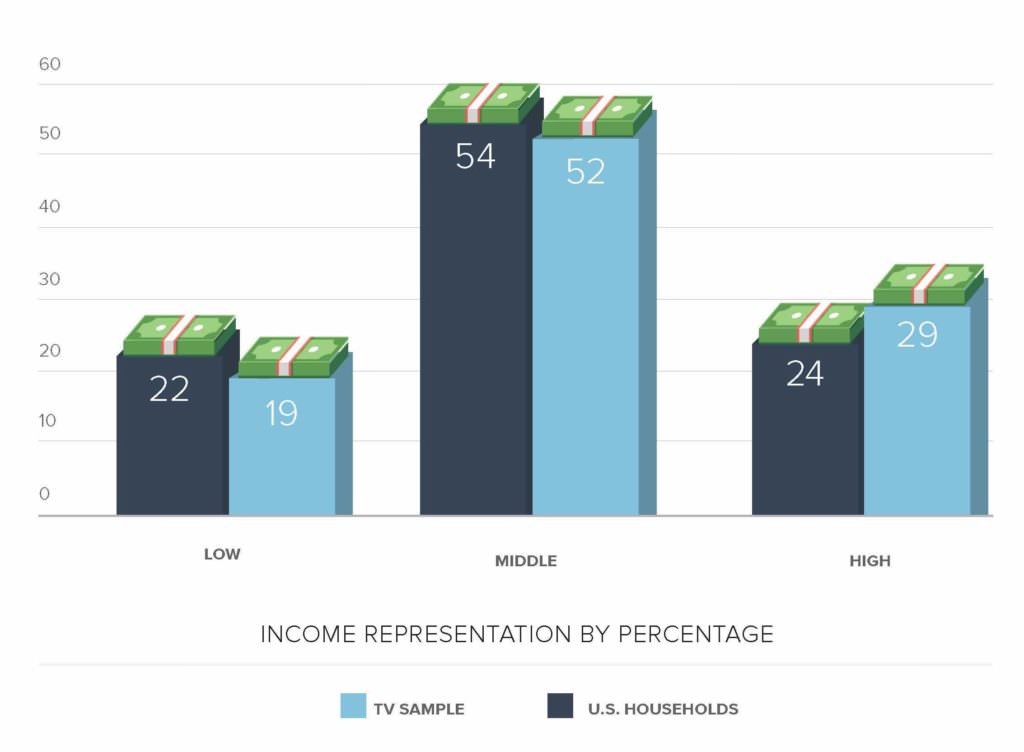

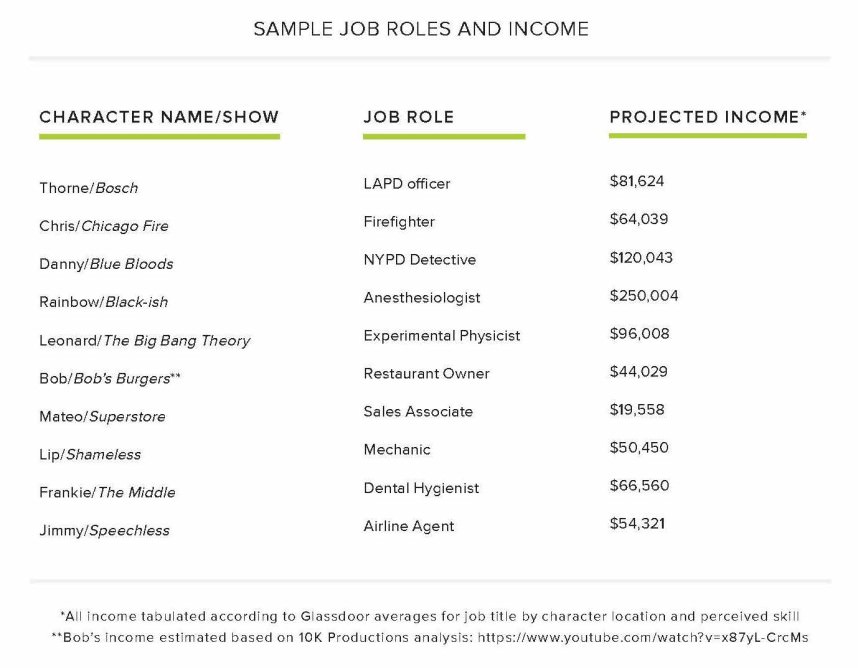

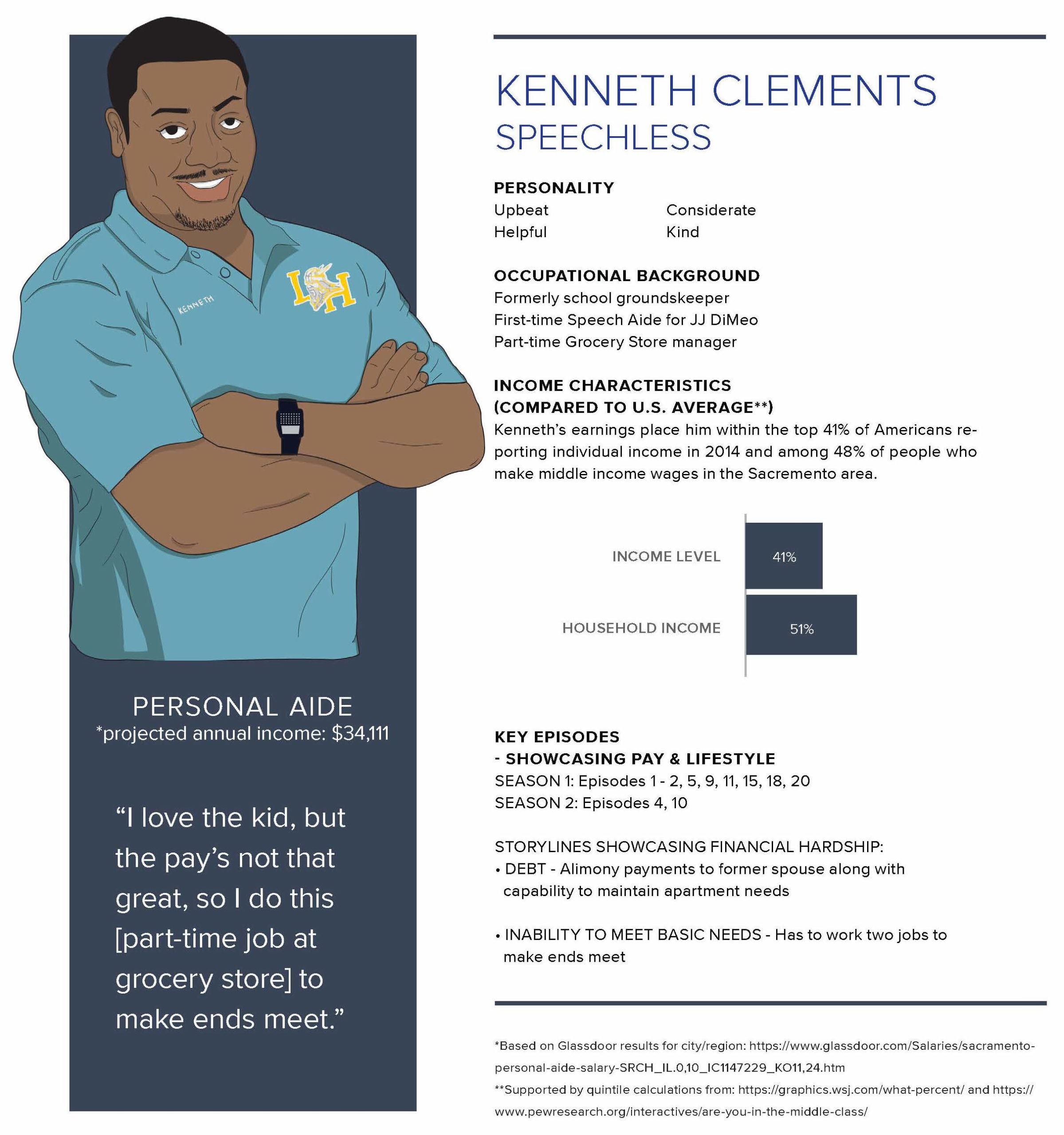

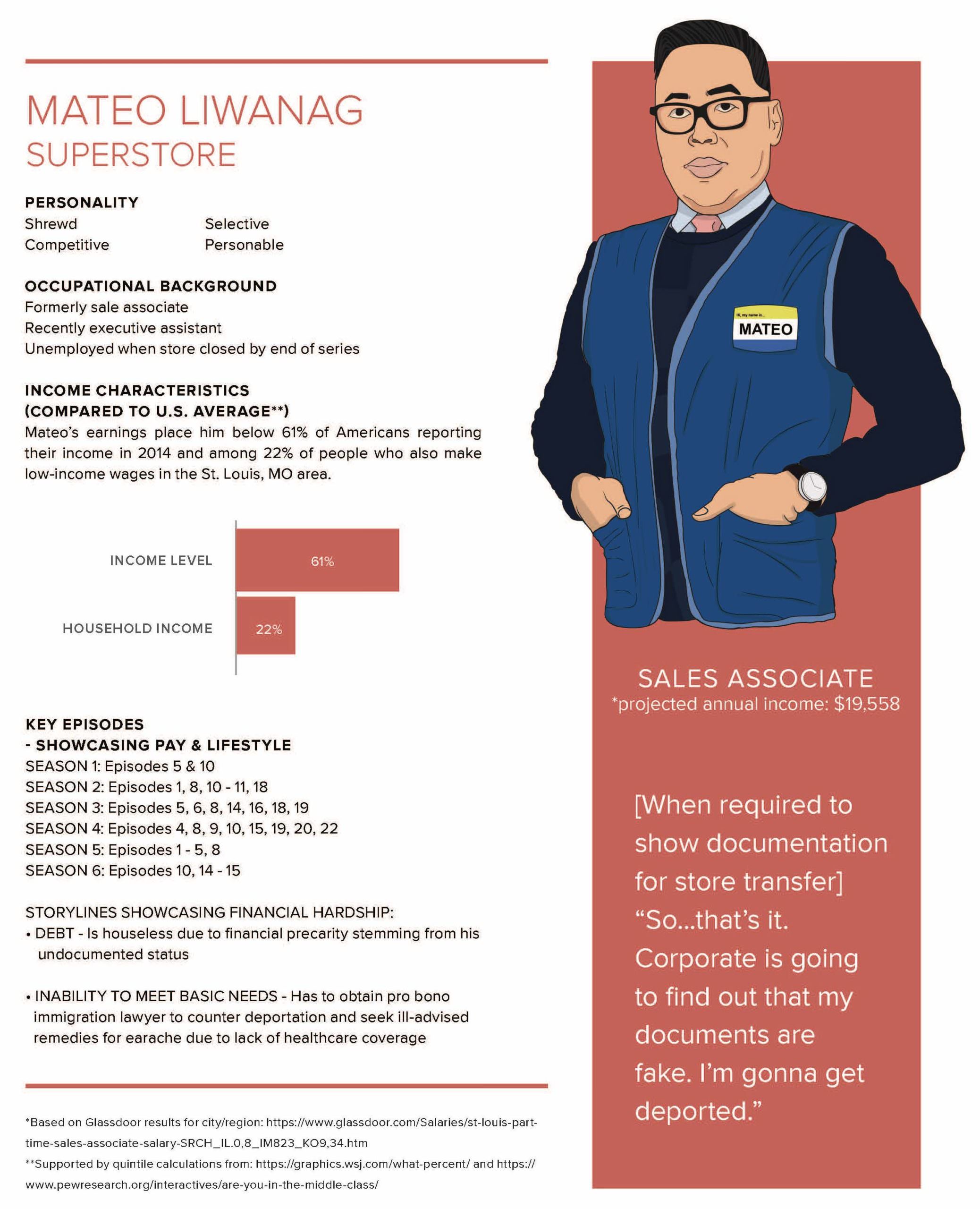

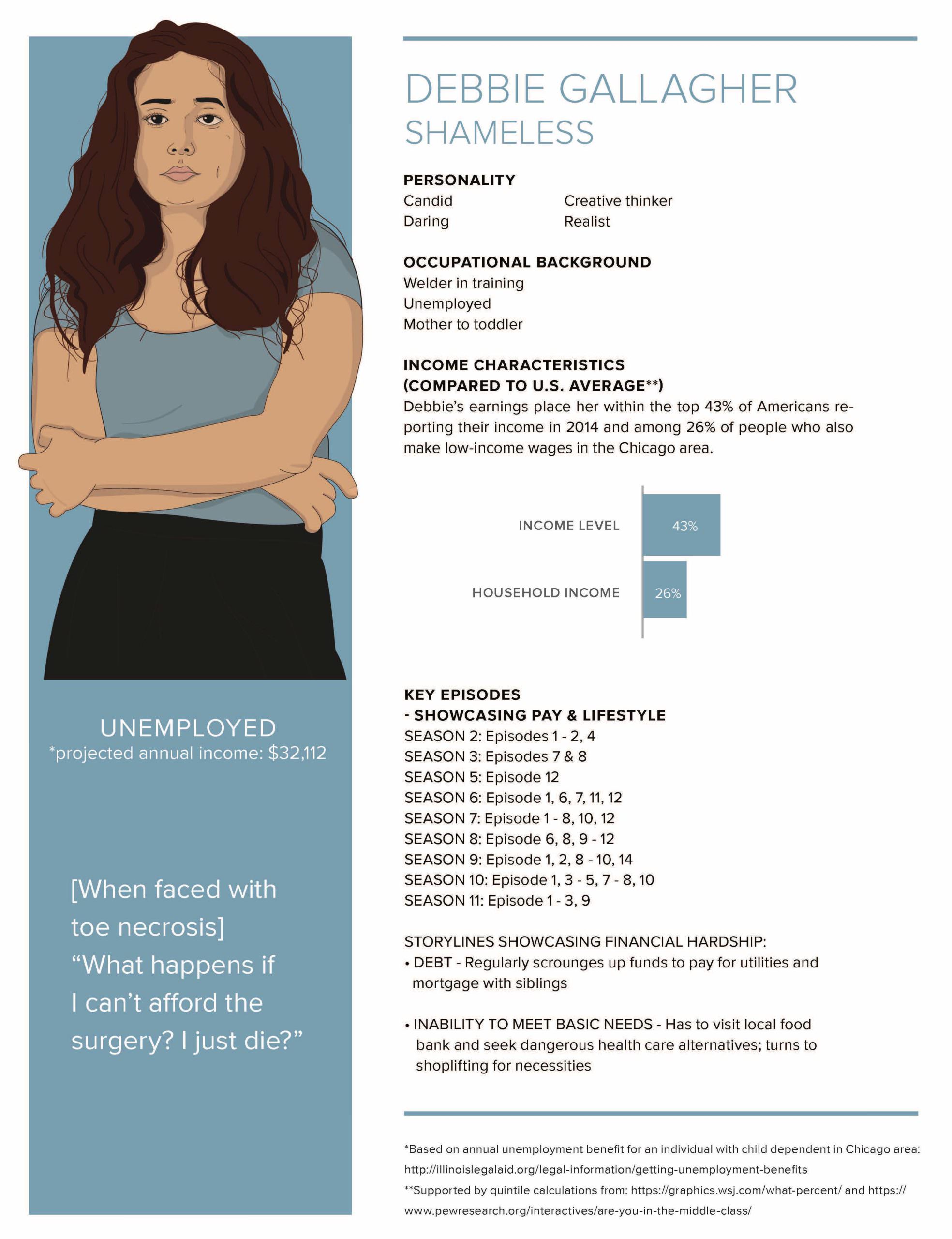

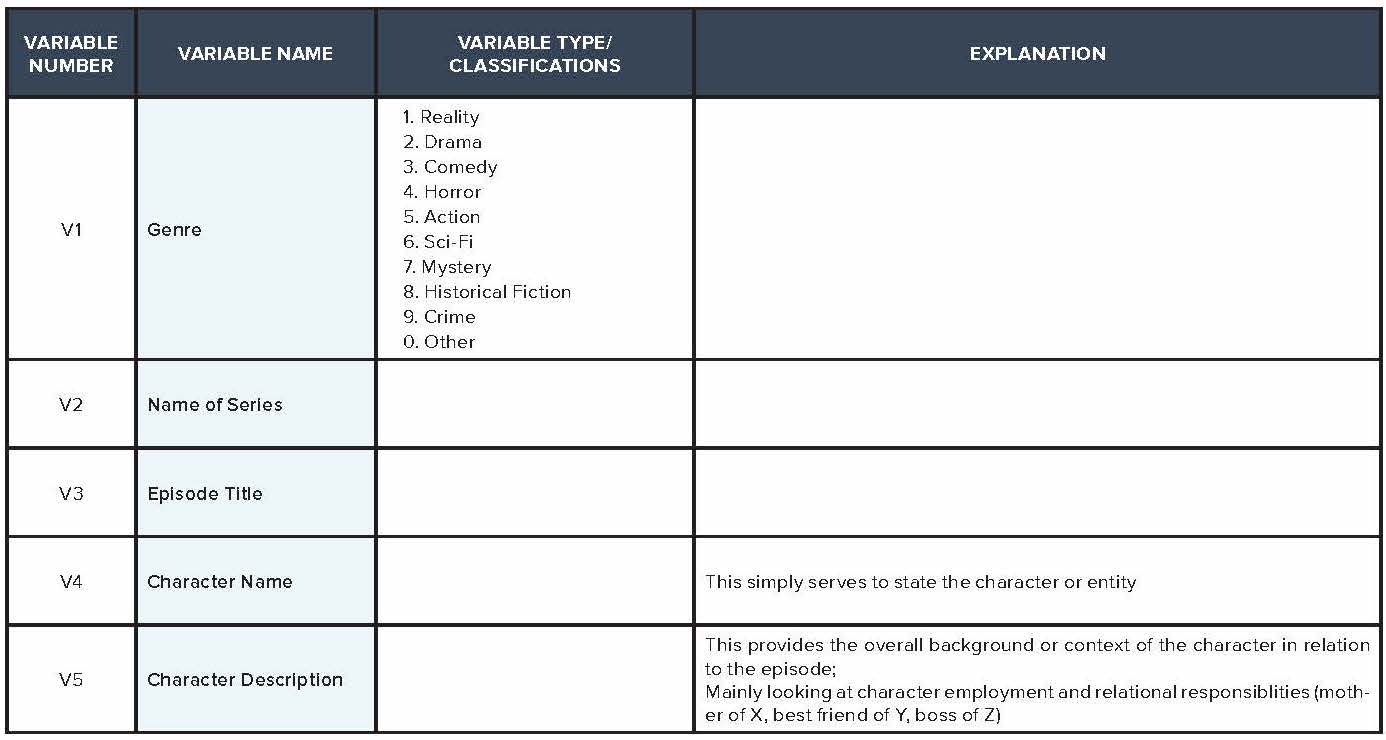

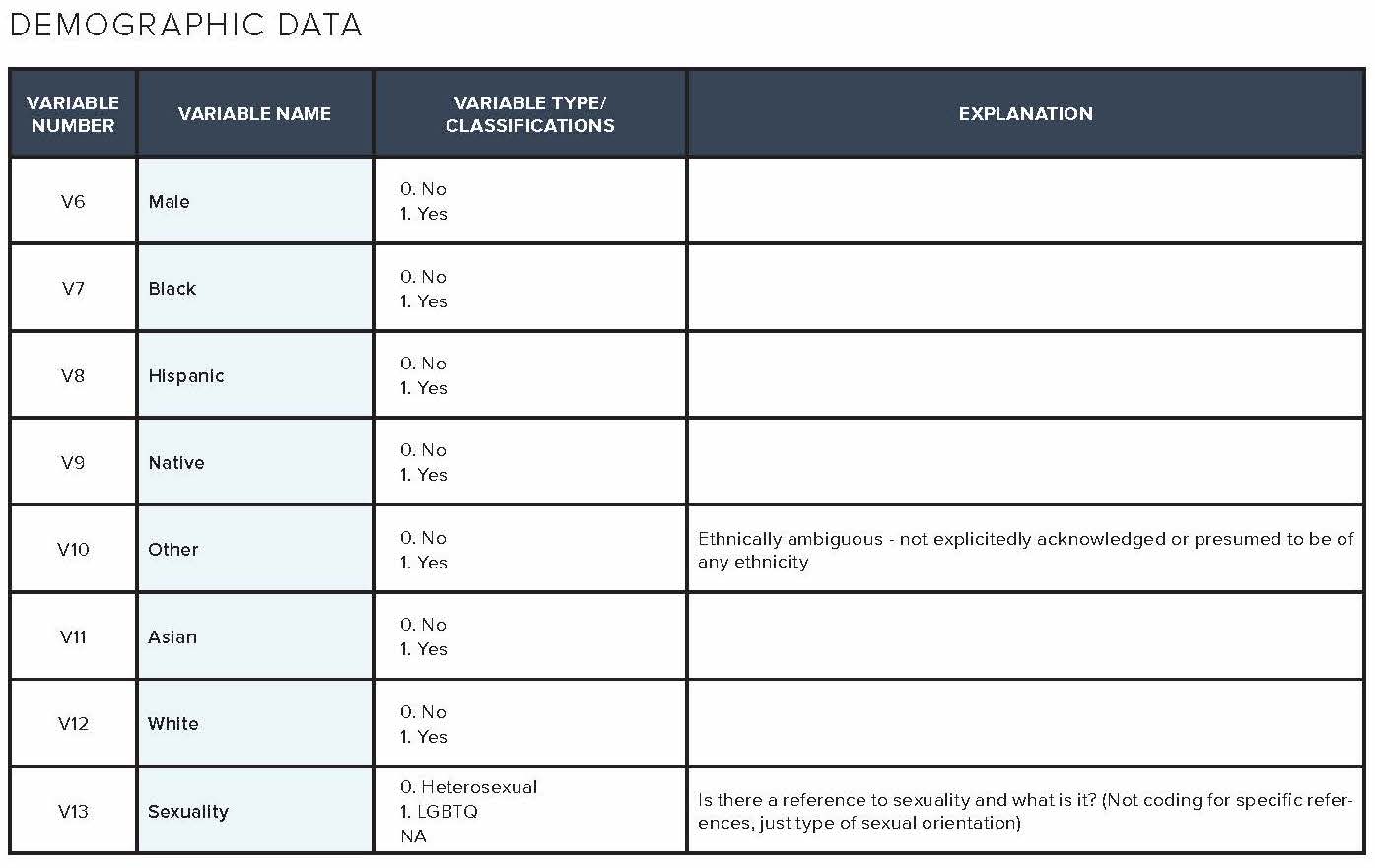

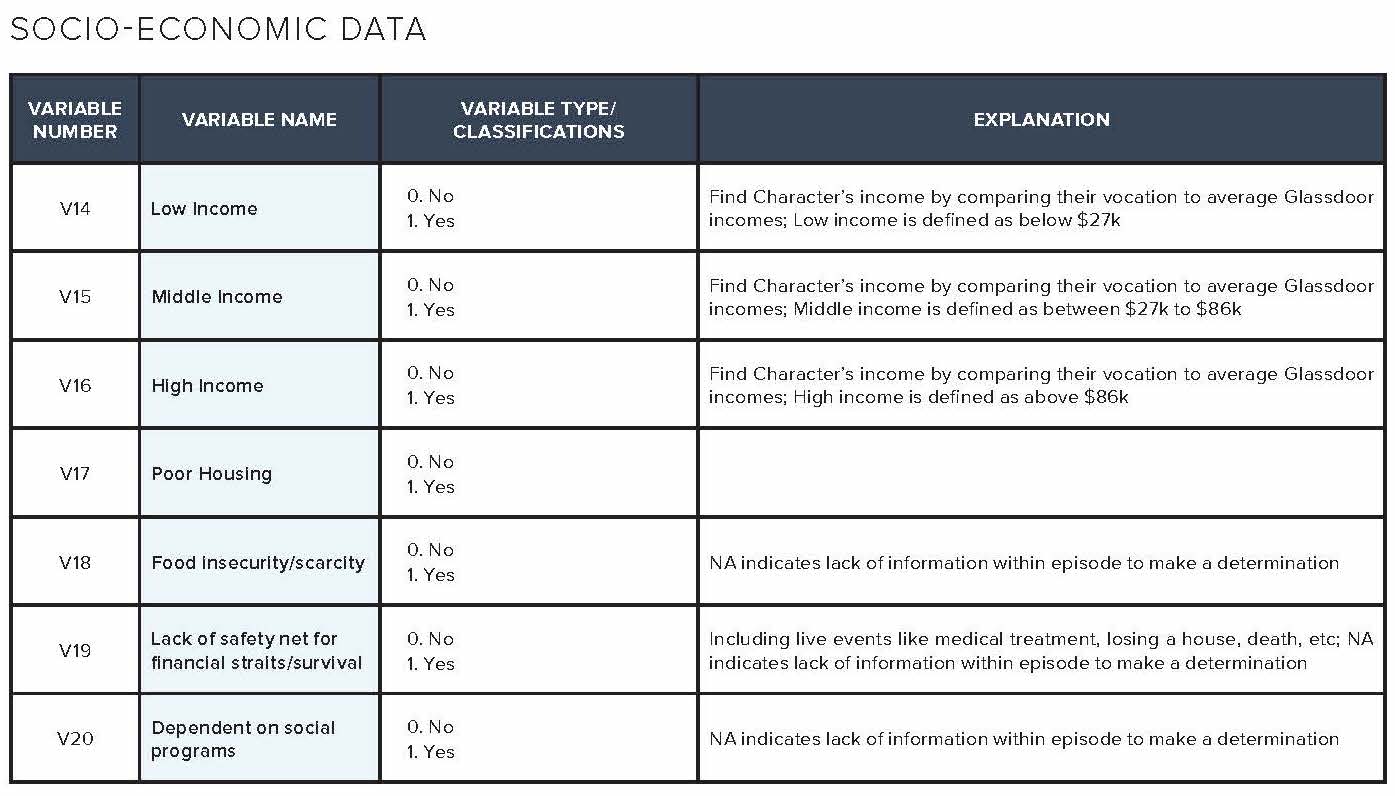

As a continuation of The Opportunity Agenda’s Power of POP series, the focus of this report draws from the cultural moment in its aim to gain a comprehensive understanding of the portrayals of income differences within streamed and broadcasted television shows. We engaged in thorough television content analysis by designing a codebook, examining broadcasted and streamed television programs, and analyzing the data gathered. The research outlined within this report examines the representation and dominant storylines associated with household income, quality of life, and the culture surrounding different income levels within popular television programs during the Fall 2017 to Spring 2018 television season.

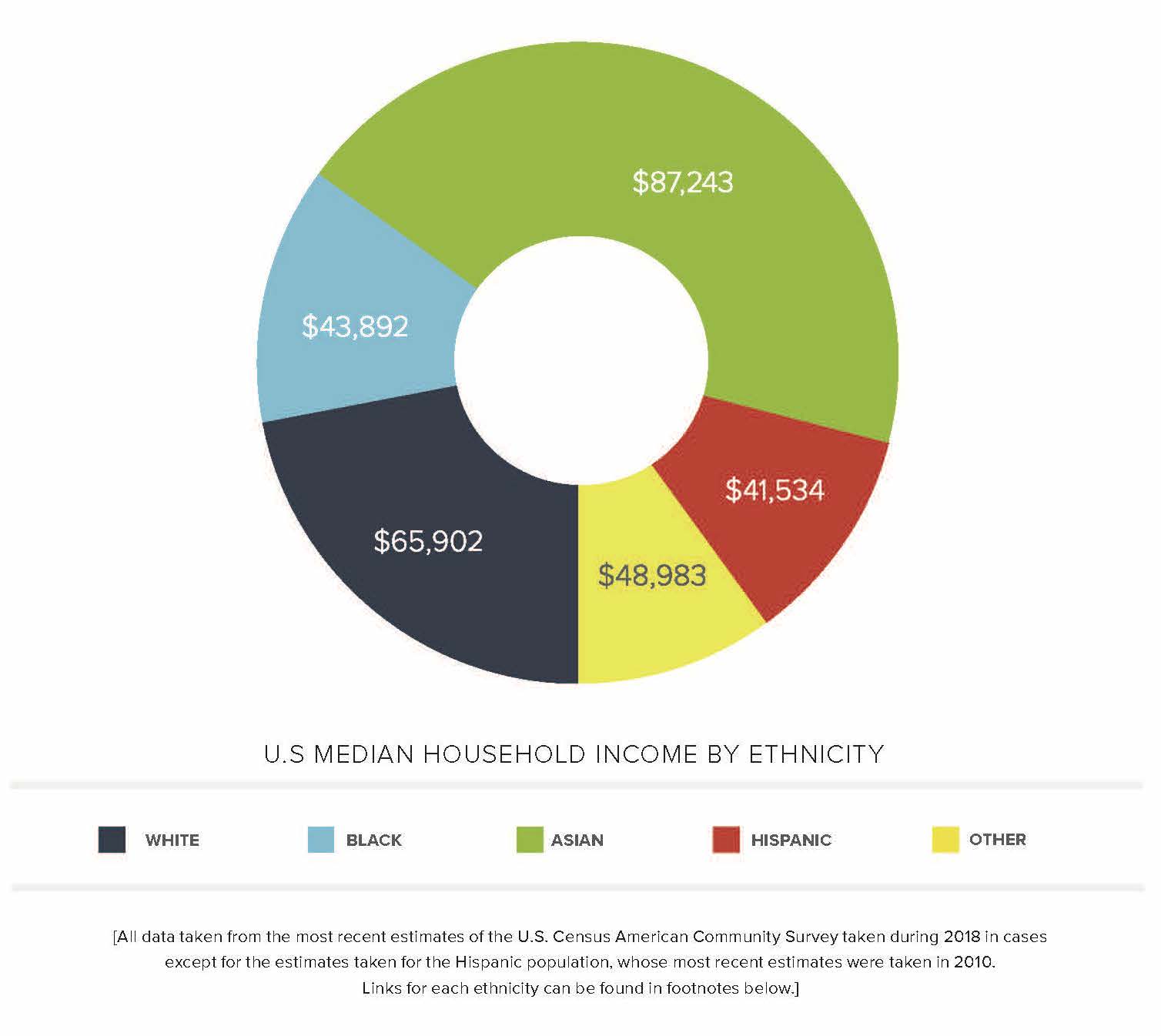

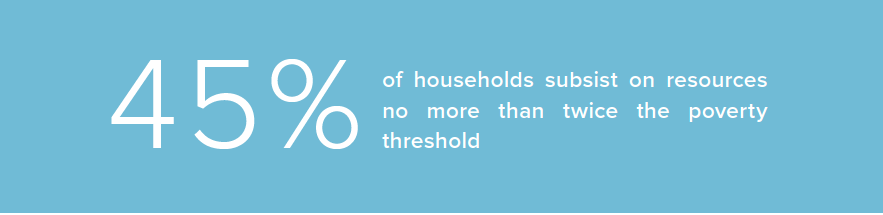

With about one in seven Americans projected to have annual family resources below the poverty threshold and the projected poverty rate in 2021 being similar to the one from 2018 (13.7%), understanding the plight of low-income households is as important as ever. Although 4.4% of people live in deep poverty in the United States, 45% of households subsist on resources no more than twice the poverty threshold. This holds true for Black and Hispanic people whose rates of poverty—18.1% and 21.9%, respectively—are nearly twice as high as their white peers. Most of these families are projected to have fallen from above to below the poverty threshold due to job loss—a major occurrence with the onset of COVID-19 in the United States.[4] It is in this economic landscape that people look for representation in the media they consume of the issues people face every day.

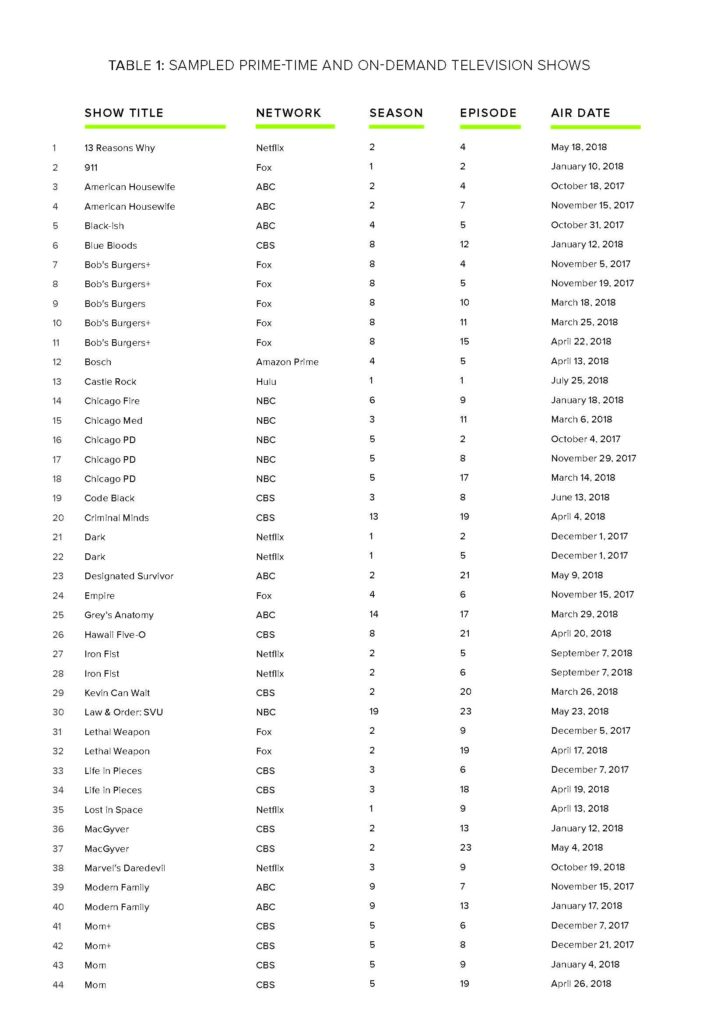

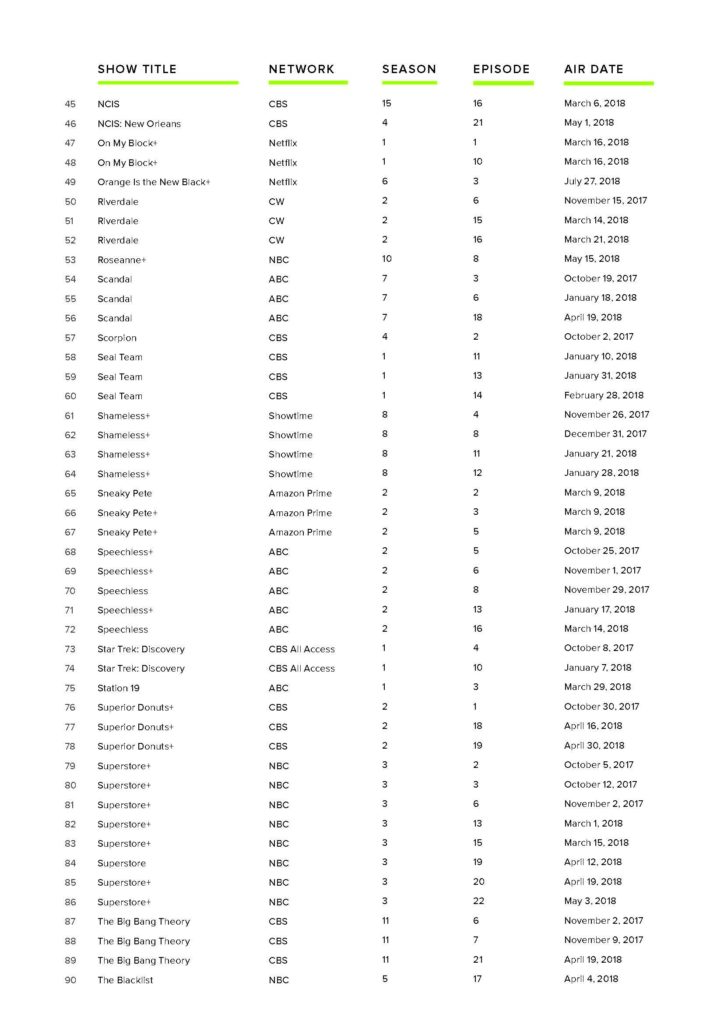

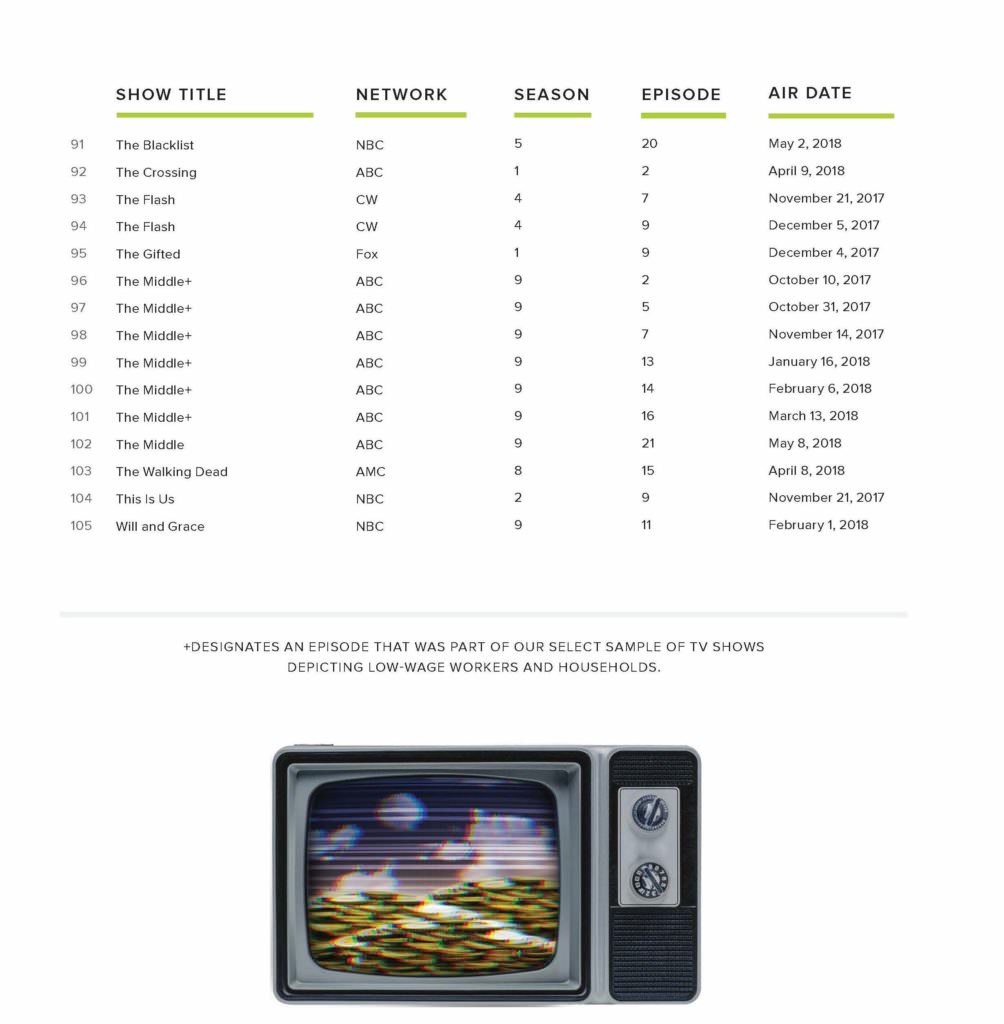

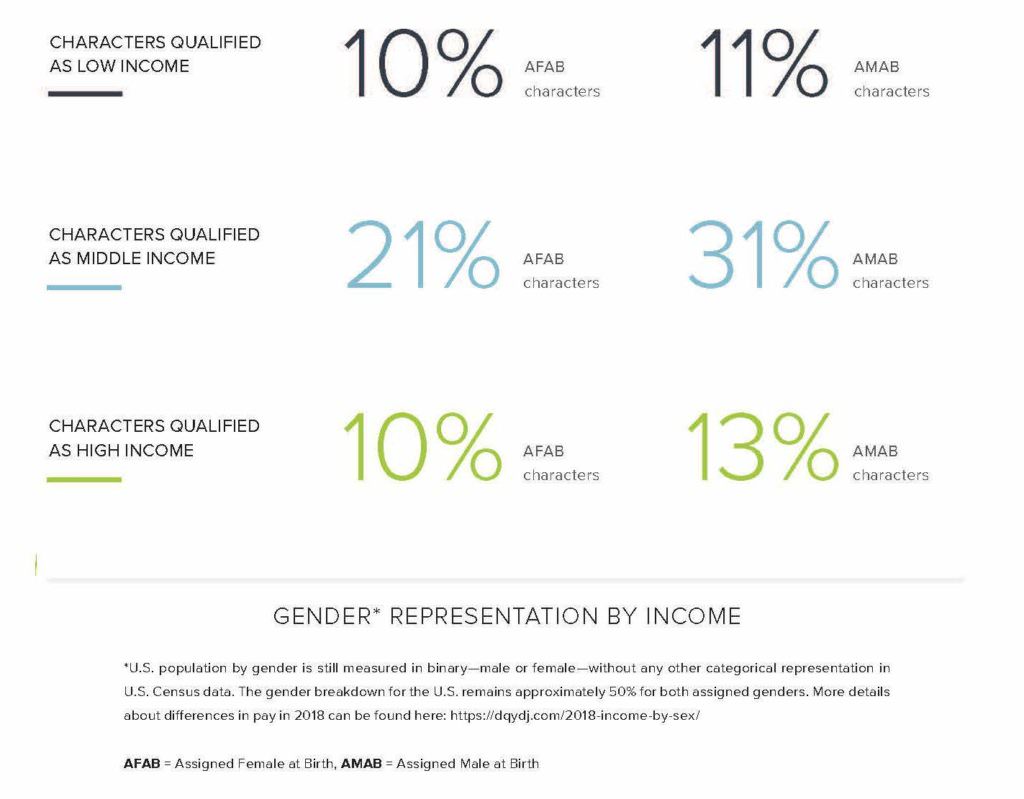

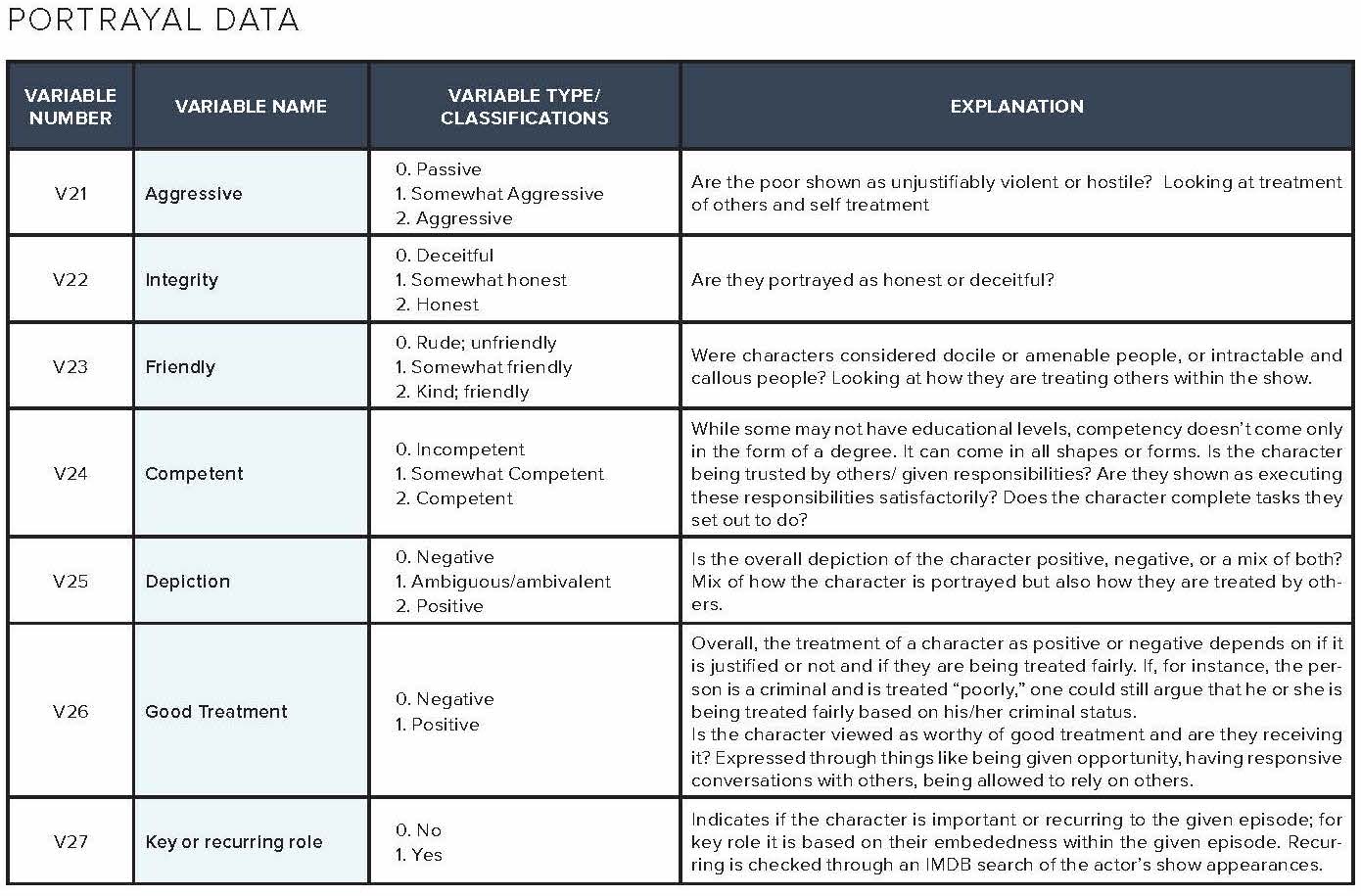

The television analysis in this report is based on content analysis of 105 randomly sampled television episodes from popular television shows aired on broadcast, cable, and streaming services divided into 70 episodes reflecting the gamut of shows available during the Fall 2017 to Spring 2018 season, and an additional 35 episodes reflecting low-wage workers from this same period based on online episode descriptions. More than 1,200 codes were analyzed by variables including demographic details such as race/ethnicity, gender, and income, as well as observance of lack of social safety net, use of social services, or other indicators of financial hardship. The codebook dictionary and a sample of the completed codebook are available in the addendum of this report.

This report is intended to offer advocates, activists, entertainment executives and creatives, media commentators, and media literacy promoters a more holistic understanding of the dominant media narratives while adding a strong voice to a growing canon of study on the impacts of media representation on narratives about directly impacted populations. This report also offers guidance and tips for improving the portrayal of working class and lower income families in popular entertainment and best practices for using popular culture to advance a social justice cause and engage new audiences.

KEY FINDINGS

Dominant Storylines and Themes Associated with Income and/or Its Disparity

- Entertainment, as exemplified by these episodes, further plays into the comparative nature of finding the affluent aspirational and the poor as unfortunate.

- Each television show avoids discussion of the precarious nature of meeting daily expenses—such as the ability to pay for utilities, phones, food, and other essentials—for those working with a low income.

We posit that this absence contributes to the culture of poverty narrative wherein stigma associated with asking for assistance when faced with obstacles to survival leads those impacted to be ashamed for shortcomings associated with the “bootstrap” narrative rather than holding the systems that deny them access to adequate housing or food.

- Health care is the leading issue used by shows within the study to garner discussions about how low-wage workers are impacted by their lack of safety net. Regardless of whether white or Black, Indigenous, People Of Color (BIPOC) characters drive the story, it’s their personal flaws—not societal ones—that land them in financially precarious circumstances.

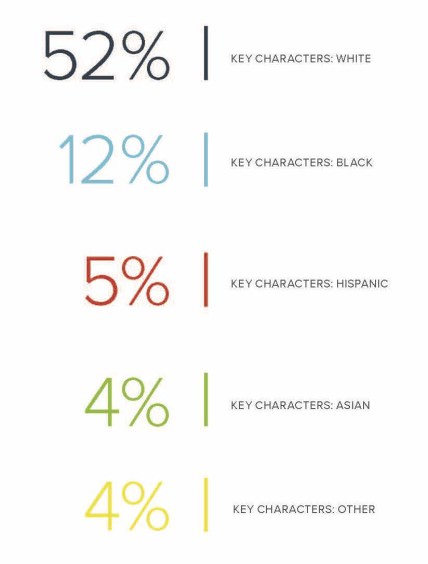

Working Class and Lower Income Character Representation

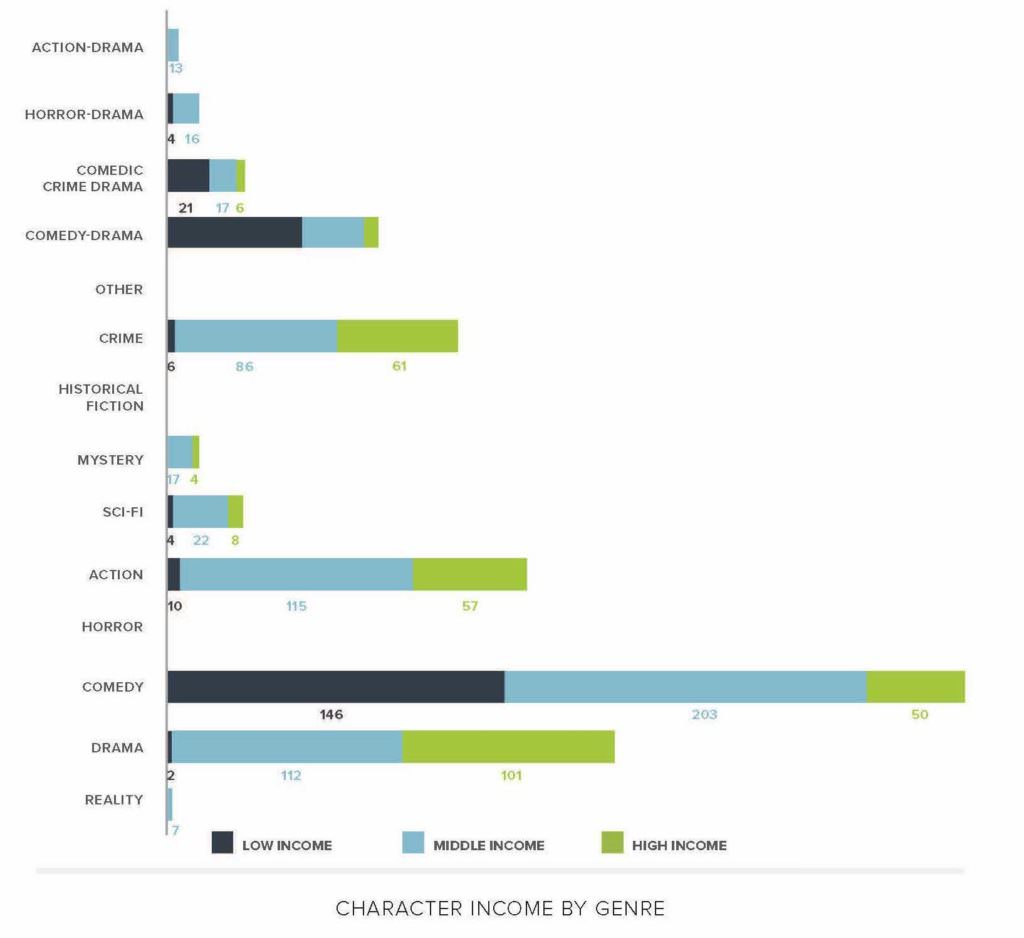

- Characters from the 2017–2018 season of television in the United States were significantly less likely to represent household incomes lower than $41,000 than any higher income.

- Low-wage workers tend to be centered as lead characters in comedic television shows, but not as much in other genres.

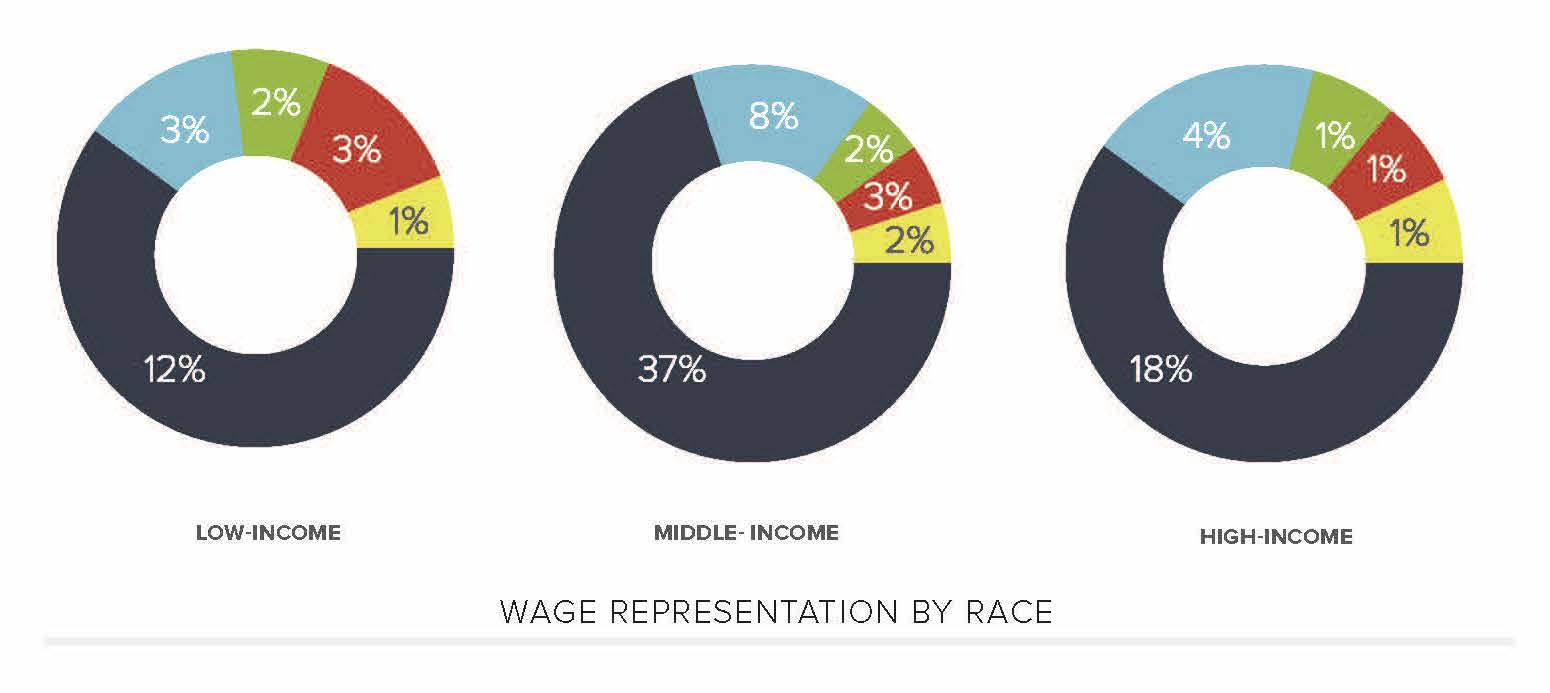

- There is an overrepresentation of white and upper-middle to high-income characters that leaves a void in representation for BIPOC families of low means.

- This is pressing in a nation consistently moving toward greater economic disparity, which is felt most drastically by the most marginalized.

RECOMMENDATIONS

If you are creating messages about economic justice issues in your advocacy work…

Know that many of your audiences are viewing incomplete and unbalanced portrayals of people with low incomes. And there are almost no portrayals of people experiencing poverty. The narratives available to audiences reveal few solutions to economic instability or poverty. At the same time, audiences are seeing that most people’s basic needs are being met with a few scattered examples of true need. It is therefore important to start communications about economic justice with some context and big-picture thinking. Without doing so, we risk our solutions seeming unnecessary or even just strange.

Fill in the gaps by providing a larger vision of what the world could look like if we had real solutions in place. Show how that world would better align with your audience’s core values. They are not seeing much of this type of expansive thinking in current TV, so we can step in and provide this big picture thinking, embracing themes like abundance, community, shared responsibility, and opportunity for all.

Frame the problem systemically. It is important to link personal stories to widespread problems, point to the systemic cause, and then move to the systemic solution. Fictional portrayals of any issue are almost always going to focus on an individual character. Watching those portrayals, as well as typical media coverage, can lead audiences to a very individualistic mindset that assumes if the problem is with the individual, so is the solution. By expanding audience’s understanding of the problem and linking a character’s challenge to the many other people experiencing that challenge, we can move them to understand the systemic solutions better.

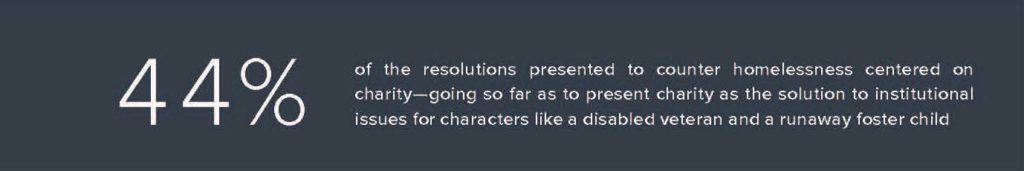

Center solutions. None of the shows we sampled portrayed systemic solutions, such as how safety net programs can alleviate economic instability, how unions protect workers, or how paid family and medical leave make it possible for families to provide for their children. Leveraging storylines can help to spotlight problems, but economic justice communicators will need to bring the solutions to the table. When solutions are left out, audiences are likely to fall into the trap of thinking that poverty, income disparities, and other barriers to economic justice are inevitable.

If you want to leverage popular television to highlight economic justice issues…

Use storylines and characters to make a point. While they are few and far between—so much so that many did not show up in our sample—some portrayals of economic injustice and solutions to it do exist. Later seasons of Superstore focused on issues such as paid family and medical leave, healthcare expenses, and labor organizing, for instance. Talking about these issues through the lens of popular TV offers an opportunity to showcase solutions in a more interesting and unexpected way than fact sheets or tweets about legislation can.

It’s also true that centering popular characters’ experiences can help build an emotional understanding and connection to your issue. Research has shown that we develop parasocial relationships with characters we regularly watch on television, identifying them (in our brains) as friends of sorts. So, talking to some audiences about the economic experiences of Amy from Superstore, for instance, could help them see those experiences in a new light and likely with more empathy. As with any individual storytelling, however, doing this needs to be balanced with other kinds of stories that broaden the focus so that audiences aren’t just focused on that individual’s plight, strengths, and weaknesses.

Highlight shows that showcase themes like community care, abundance, and even joy, in addition to those that provide portrayals of economic injustice. While more recent releases such as Netflix’s Maid and Squid Game provide some of the low-income character representation we would like to see more of, audience appreciation for Ted Lasso—a show equally about rich people and being a person who cares for others—shows that audiences are primed for more representation of community care. By building upon the abundance narrative over scarcity, creators can build worlds that show how communities support their own with love, care, and joy, bringing this positive energy into their advocacy for a better life for everyone. ABC’s upcoming television show Abbott Elementary appears to be a potential example of what the integration of community care, Black joy, and advocacy for better financial support can look like on television.

Monitor shows that offer opportunities to spark conversation about income inequality or instability. To keep up with opportunities to leverage relevant plotlines, formally select a few shows that appeal to your target audience and follow them. Watching whole episodes is not even necessary as there are many recaps available online on sites such as Vulture, EW online, and ShowSnob.

Choose your timing carefully. On the one hand, things move quickly online and issues come in and out of focus at a rapid pace. It is typically a good idea to respond within a 48-hour window for simple social media engagement and within a week for more detailed media pieces. On the other hand, social media engagement with television content spikes significantly at certain points within a show’s schedule. For series that consistently engage in narratives about poverty and economic instability, look for opportunities such as premieres and finales. Significant episodes and major award shows also draw significant audiences. Use these moments to live tweet, host a Twitter chat, or host an online watch party.

If you want to influence portrayals of income instability and poverty…

Give positive reinforcement for good portrayals. This could be as simple as encouraging fans to thank show writers and networks for an authentic character or storyline via social media. Or, you could create an award to the networks or individuals using their platforms to tell compelling stories about people with low incomes or that promote a social justice narrative. Positive reinforcement is a good place to start to both encourage good storytelling and lay the foundation for relationships with creators.

Create your own hashtags or memes to draw attention to representations. For example, #StarringJohnCho memes went viral as people photoshopped John Cho into famous movie posters that starred white male actors, creatively criticizing the lack of diversity in Hollywood. The #OscarsSoWhite hashtag was started by April Reign to raise the same issue and sparked a national debate that resulted in changes in the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Engage progressive fandoms. Find the online communities of popular shows where fans are already gathering to talk about them. Create toolkits or messaging guides around a particular series to spark fan engagement.

Encourage networks to engage with and hire people who have experienced economic instability. We need more stories centered on low-income characters written by people who have lived through poverty for prolonged periods. This is particularly true for houseless representation and should be a component for any creative work related to this issue, whether it is a television program or advocacy campaign. Directly affected writers can bring their lived experiences to light in a way that helps us move from a voyeuristic, socially distanced interaction to one of better relatability and nuanced understanding. After all, if the producers and writers of Modern Family and Maid can bring their personal issues into scriptwriting, why can the same not become true for character portrayals unseen in other recent television shows?

Build relationships with script writers, producers, and show runners. Introduce script writers, producers, and show runners to stories that not only are personal and compelling but also are diverse and affirmative and more fully depict the experience of people living in economic instability. Note that to be effective, this strategy may require more significant long-term investments in both time and resources.

If you want to add positive portrayals to the mix…

Rewrite shows or plots to show how they could tell a fuller story of economic insecurity and what we can all do about it. You can use social media to spread your ideas about what popular TV could look like in this regard. To do this, put yourself in the shoes of a Hollywood writer who wanted to ethically depict characters experiencing poverty and imagine what they would come up with. You can also engage in a “what if?” exercise online, inviting your audience to help fill in how a show could depict the low-income experience more realistically and compassionately. Or suggest a whole new TV show that would accurately show the causes and solutions to poverty.

Partner with artists and creatives to tell new stories about economic instability and poverty. Artists should be included in strategic conversations early because their perspectives often lead to out-of-the-box innovations. Just like graphic designers, researchers, or anyone else with a specialized skillset you wouldn’t ask to work for free, keep in mind that artists should also be paid. Consider budgeting ahead of time to be able to include their talents.

Produce your own content. Creating your own content is now more accessible than ever. Creatives with limited resources are making use of content-sharing platforms like YouTube, TikTok, and SoundCloud and crowdsourcing sites like Kickstarter to launch independent projects and tell otherwise untold stories. Videos, web series, and podcasts are within reach, although we recommend partnering with a creative that is skilled at storytelling in your chosen format to maximize the impact.

If you want to help audiences become educated consumers of entertainment and other media…

Organize watch parties and discussion groups. Assemble around helpful, harmful, and nuanced portrayals.

Provide guides. Develop study guides and curricula that help support young people to become more educated consumers of entertainment and other media.

Make your organization a resource. Offer cultural critiques of select shows on a regular basis. Pitch yourself as a resource to media who cover pop culture and are interested in how portrayals interact with real-life experiences.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Opportunity Agenda wishes to thank and acknowledge the many people who contributed their time, energy, and expertise to the research and writing of this report. The report was researched and written by Porshea Patterson-Hurst, Charles Sherman, Wendy Li, and Wesley Huang, with guidance and editing from Adam Luna, Julie Fisher-Rowe, Elizabeth Johnsen, and Lucy Odigie-Turley of The Opportunity Agenda. The illustrations were created by Justin Nguyen of Yellow Panda and the design and layout were completed by Lorissa Shepstone, Being Wicked. Final proofing and copy editing were conducted by Margo Harris. Special thanks to Brian Erickson, Christiaan Perez, and J. Rachel Reyes for outreach and distribution coordination. Additional thanks to Caty Borum-Chattoo of American University and Josh Gwin of Marion Polk Food Share for field knowledge.

This report and the work of The Opportunity Agenda are made possible with funding from The Annie E. Casey Foundation, The Ford Foundation, The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, The JPB Foundation, The Libra Foundation, The Marguerite Casey Foundation, The Nathan Cummings Foundation, NEO Philanthropy, The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, The Tow Foundation, Unbound Philanthropy, and Wellspring Philanthropic Fund and would not be possible without the contributions of time, treasure, and talent from our many supporters.

ABOUT THE OPPORTUNITY AGENDA

The Opportunity Agenda was founded in 2006 with the mission of building the national will to expand opportunity in America. Focused on moving hearts, minds, and policy over time, the organization works with social justice groups, leaders, and movements to advance solutions that expand opportunity for everyone. Through active partnerships, The Opportunity Agenda synthesizes and translates research on barriers to opportunity and corresponding solutions, uses communications and media to understand and influence public opinion, and identifies and advocates for policies that improve people’s lives.

1 https://opportunityagenda.org/explore/resources-publications/power-pop

2 https://opportunityagenda.org/explore/insights/more-just-fad-power-cultural-influencer

3 https://jacobinmag.com/2021/11/squid-game-ssangyong-dragon-motor-strike-south-korea/

4 https://www.urban.org/research/publication/2021-poverty-projections