Dominant Storylines & Themes

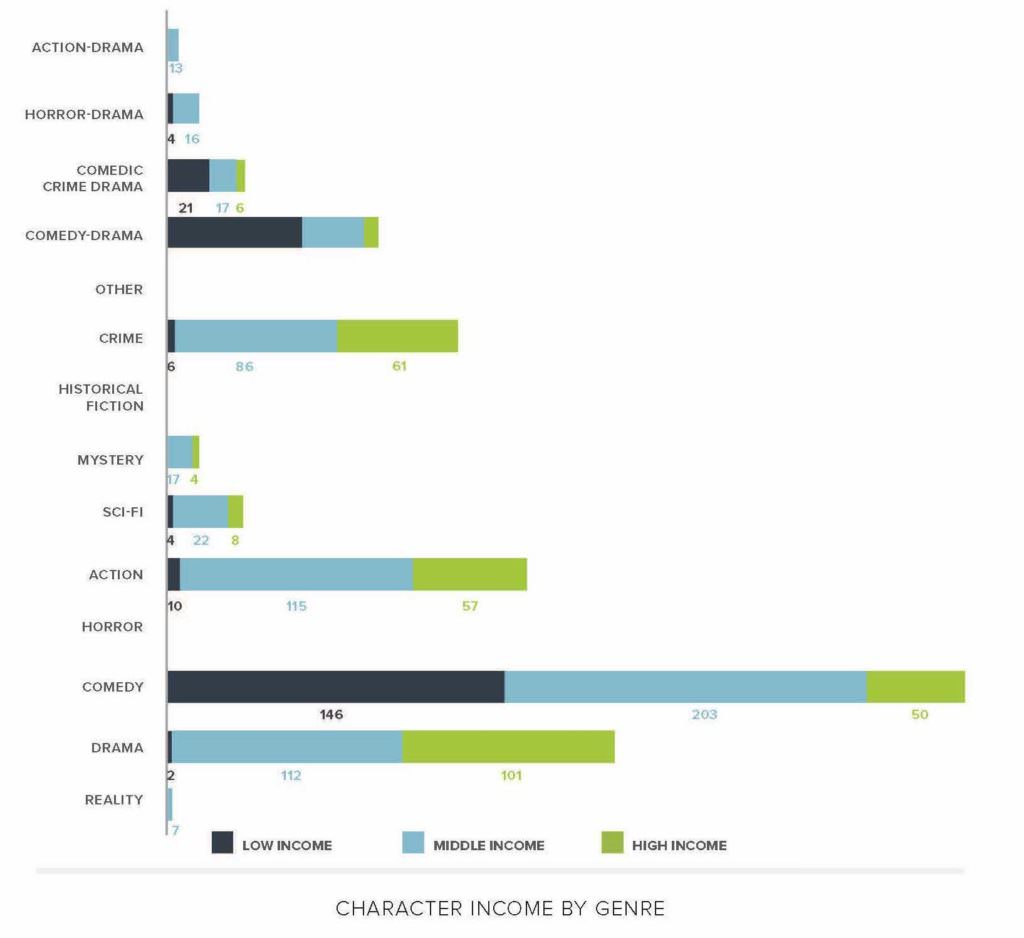

This section provides an overview of the dominant genres, storylines, and themes associated with low-income characters and the lifestyles of characters making low wages more broadly. As the graph below attests, character representation among those making this level of income is not widely covered in most genres. One genre does reign supreme, however, dominating representation of low-wage workers and their strife. That genre? Comedy.

As a quote attributed to Mindy Greenstein goes: “Comedy is not the opposite of darkness, but its natural bedfellow. Pain makes laughter necessary; laughter makes pain tolerable.”

This concept seems to generate a great deal of steam within the television industry, as each of the shows focused on characters receiving low income within this study fall under the comedy genre—51 out of the 105 episodes in this sample are some form of comedy. Even the grittier, cross-genre (i.e., critically listed as comedy-dramas) shows like On My Block, Orange Is the New Black, and Shameless make sure to include the absurd and darkly comedic sides of their stories in each episode. For instance, in the Shameless episode “A Gallagher Pedicure,” Debbie Gallagher suffers a foot injury while training as a welder. Because she is a student without healthcare coverage and used to less ethical work-arounds to major issues in her life, she asks her middle school–aged brother to ply off the dead toes as she has no means to afford the surgery the doctor told her she needed.

In fact, most of the examples we found of characters confronting an issue without enough money to cover a direct need centered around medical care. On the “Health Fund” episode of Superstore, the health concerns of various staff members are confronted when Mateo discusses his inability to see a doctor for his ear infection due to a lack of health coverage and his undocumented status. He, too, resorts to using nonmedical means of recovery, despite the mutual aid fund concept that floats around during the episode. The episode ends by touching upon the real-world similarity to Walmart’s infamous canned food drive for its own employees[15] by having Mateo’s co-workers chip in one hundred dollars for a cure. Yet even this show of goodwill is twisted when he announces that he will instead use it to purchase a bag, possibly highlighting the fickleness of capitalistic interest versus self-care, as one hundred dollars is likely to cover more expense for a low-end designer bag than it ever would in the costs of healthcare coverage.

THEME: BROKE CULTURE

Comparative experiences between keeping up appearances and satisfying an actual need is yet another storyline that occurs in many of the episodes that cover low- or low-middle income characters. Episodes “Please Don’t Feed the Hecks” and “Thanksgiving IX” of The Middle show the upwardly mobile Hecks family working through their moments of “brokeness” despite generating enough household income to have sent two of their children to college. In “Please Don’t Feed the Hecks,” Sue, a sophomore in college, and her best friend/roommate Lexie are forced to live in Lexie’s car for a few nights due to the people they’d sublet their apartment to during the summer renting their place out as an Airbnb. They are stymied from booting the Airbnb renter out themselves because Sue is conflicted about getting into the good graces of the professor who is renting their place. By the end of the episode, they are back in their apartment and their brief experience with houselessness is little more than an anecdote.

The Hecks family continues to show that their proximity to being broke is relative in the “Thanksgiving IX” of The Middle. At the beginning of this episode the father, Mike, disputes a charge that he later finds out was his wife treating herself to a coffee. When the company shuts down usage of the card because of the claim, the family trip to a relative’s house for the holiday is put into turmoil. They run out of gas on the drive to the relative’s house and have no cash or other means to pay for or borrow the money they need to return to the road without the credit card they usually rely on. It is by their daughter Sue’s ethically unclear ingenuity to take money from the water fountain of a nearby mall that they are able to get on the road again.

Outside of these circumstances, we ran into no storylines centered around characters struggling for an immediate need. As with the cases exemplified by The Middle, being broke is often related to the level of means available to any character at any given period of time rather than a fear of having actual utilities or other needs cut off. In fact, we found few episodes even mentioned a concern for food or shelter. When adjusting for the household income, we find that each parent—Frankie and Mike—bring in around $65,000 annually, which is later upgraded when Mike receives a promotion toward the end of the series, now making $74,975—an estimate we deduced from Glassdoor averages for this job title in the character’s home location. This is in addition to knowledge that they could afford sending their first child to college and business school and sell ownership in a family business to pay for their second child’s college tuition. Their first child, Axl, is able to depend on the safety net of his family such that while he lives with his parents, he goes from making $41,600 as a bus driver in episode 2 of their final season to $49,463 as an entry-level plumbing supply salesperson in episode 21. Not only does he have the safety net of living with his parents—albeit in cramped circumstances—but he also is able to pursue work in his field of choice within his first 6 months out of school without fear of being houseless or unable to pay for necessities.

The fact that the Hecks family still sees themselves as broke despite showing all indication of maintaining a lifestyle commiserate with their cost of living bears questioning of the concept of “brokeness” and who truly meets it.

THEME: WORTH

As discourse around wages and how people find themselves on the various rungs of the class ladder persist in society, many of the stories in our study that followed characters living within the low to low-middle rungs tend to explain why their pay does or does not reflect their actual “worth” as humans.

For the Gallagher family of Shameless, they are making the best of a hopeless situation as children of a conman and an addict living in a home falling apart in South Side, Chicago. The siblings often endure dehumanizing situations that limit their self-worth, such as an instance in “Gallagher Pedicure” where Debbie Gallagher waits in a dingy basement line with her toddler in tow to pick up a mismatched box of food at a local food pantry. They also resort to crafty means because they have learned not to trust in good from the world yet strive to remain good at heart so that they are at least morally superior to their unscrupulous father. Similar to their real-world counterparts, the Gallaghers hold distaste for the wealthy while also striving to become financially successful themselves—a great irony of morality under a capitalist system.

In Mom, the mother and daughter relationship between the series’ main protagonists, Bonnie and Christy, presents as a narrative around rehabilitation both in health and life with Christy learning to forgive and understand her mother’s transgressions as an addict during her childhood. The mishaps and adventures that the two go on serve to “heal” the rift between them and show that anyone is worthy of a comeback, even if that comeback isn’t under the most ideal of circumstances.

The issue with these sorts of tales is that they frame these primarily white families as falling upon hard times or having drawn a bad lot in life to now depend on low-income options. Comparatively in Superstore, their cast members, with a fairly representative spread of BIPOC characters, don’t get a lot of exposition for how they ended up in low-wage jobs. Even this show provides reasoning for why one of its white characters, Jonah, works at Superstore, buying into this thematic framing that is rooted in the comfort of intrinsically linking race and class.

THEME: OTHERING AND VOYEURISM

While it is the nature of capitalist society to treat engagement or watching of the affluent as stoking ambition within people with lower levels of income, the opposite, the rich having a level of fascination in consuming the experience of people from lower classes, is downright voyeuristic. In season 8 of Shameless, we see Carl Gallagher get entangled in a relationship with a young addict, who we later learn is from a well-to-do family and pulled herself into the Gallagher’s orbit because she is enticed by their lower-class struggle to survive. This character’s journey is reflective of the phenomenon of “slumming drama,” wherein the rich become interested in, and even sexually attracted to, the poor. It is also a blatant usage of the culture of poverty narrative, which insists on presenting issues faced by low-income characters as personal rather than structural developments.

The rich sense that the poor have something they lack—bodily strength, excitement, unrestrained sex, or a simple authentic life—and want to possess it. Presented in a sensationalist mode, slumming dramas elicit a titillating reading or viewing experience.[16]

Not only does the exploitative nature of these relationships harm lower income people, but it also furthers their victimization. Yet, it is a practice that has remained somewhat acceptable in popular society as it plays into the “culture of poverty” narrative that has influenced social scientific research for decades and has informed both politicians’ (predominantly Republicans’) and the public’s understanding of poverty. This concept posits that living in persistent poverty results in the formation of a specific culture that, passed on over generations, produces attitudes and values that yield to dysfunctional behavior.[17]

Ironically, with the people behind the camera of these television programs coming from circumstances completely unlike their low-income characters, they also ask the audience to view these characters in a voyeuristic, judgmental lens—without their consent.

THEME: PERSONAL FAILURE PREVAILS, NOT STRUCTURAL EXPLOITATION

Indeed, prevailing narratives of individualism determining one’s lot in life (i.e., every person having the ability to pull themselves out of abject circumstances into a more favorable lifestyle) lead to findings in the Power of POP study looking much like those of Conrad et al., wherein individual causes of homelessness are attributed to individual or group decisions, actions, or behaviors, including criminal behavior, mental illness, substance use, distability, or failure to meet bills.[18] There were very few instances where characters living within these circumstances ever aligned their issue with a systemic shortcoming or oversight, sparing the sarcastic and inauthentic Frank Gallagher of Shameless or the “Health Fund” episode of Superstore, which relies on the audience to pick up on the dysfunction of the health insurance industry.

This bias stems from the “culture of poverty” frame, which blames the individual for failing to obtain a better life, consequently shifting the blame of addressing the problem of poverty on the individual. This approach furthers a centuries-old binary of “the deserving” and “the undeserving” poor, which is equally rooted within white American racist attitudes that insist Black people are naturally inferior. With a focus on the failings of the individual, this narrative emphasizes personal inadequacies including addiction, laziness, or “making the wrong choices” or “bad decisions.” By instigating a separatist culture, those with influence and power are exonerated from responsibility for discriminatory laws and institutions.[19]

This furthers an argument for the use of charity to maintain the status quo of systemic behavior among the classes. In fact, the television episodes in the Conrad-Perez et al. study found 44% of the resolutions presented to counter homelessness centered on charity—going so far as to present charity as the solution to institutional issues for characters like a disabled veteran and a runaway foster child. The fact that the charitable solutions found for both of these cases were only stopgap measures makes clear that charities are often not organized to change the structural conditions upon which homelessness rest. Nevertheless, this frame went unchallenged, instead opting to pull on the heartstrings of viewers who want to see the main characters as heroes, not perpetrators of bad systemic practices. Centering storytelling directly on houseless characters could instead use their brushes with charity to highlight the many stopgap measures that persist within these systems without providing long-term solutions to eradicating poverty.

16 Gandal, K. (2007). Gandal’s Class Representation in Modern Fiction and Film.

17 Lewis, O. (1959). Five Families: Mexican Case Studies in the Culture of Poverty.

18 Conrad-Pérez, D., Chattoo, C. B., Coskuntuncel, A., & Young, L. (2021). Voiceless Victims and Charity Saviors: How US Entertainment TV Portrays Homelessness and Housing Insecurity in a Time of Crisis. International Journal of Communication, 15, 22.

19 Lemke, S. (2016) The Nation: American Exceptionalism in Our Time. In: Inequality, Poverty and Precarity in Contemporary American Culture. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.